Some time ago I did a piece here on the writing of my story, "Mariel", which appeared in the Dec. 2012 issue of ELLERY QUEEN MYSTERY MAGAZINE. Finding myself overcome by events and coming up dry on the deadline for this month's entry in the SleuthSayers sweepstakes, I decided to make the story available (in two parts due to its length) to anyone who wants to read it. I hope that you will, if you haven't already, and that you enjoy meeting it's young heroine.

Mariel

THE NEIGHBOR watched Mariel approach through his partially shuttered blinds. She cruised down their quiet cul-de-sac on her purple bicycle, her large head with its jumble of tight curls swiveling from side to side. He thought she looked grotesque, a Shirley Temple on steroids. Mariel ratcheted the bell affixed to her handlebars for no apparent reason and stopped in front of his house. He took a step back from the window.

His house was one of three that lay along the turn-around at the end of Crumpler Lane and normally she would simply complete her circumnavigation of the asphalted circle and return to her end of the street. This time, however, Mariel’s piggish eyes swept across his lawn and continued to the space between his house and that of his neighbor’s to the north, who despised the child as much as he did, if that was possible. A crease of concern appeared on his freckled forehead and he took a sip of his cooling coffee.

Suddenly she raked the lever of her bell back and forth several times startling him, the nerve-wracking jangle sounding as if Mariel and her bike were in his living room. He felt something warm slide over his knuckles and drip onto his faux Persian carpet.

Hissing a curse about Mariel’s parentage, he turned for the kitchen and a bottle of stain remover. “Hideous child,” he murmured through clenched teeth, “Troglodyte!” What was she looking for? More than once he had chased her from his property after he had found her snooping around his sheds and peering in his windows. Though he had complained, her mother had proved useless in controlling the child. She was one of those ‘single moms’ that seemed to dominate the family landscape of late, and had made it clear that she thought he was overreacting.

He recalled with a flushing of his freshly razored cheeks, how she had appeared amused by the whole thing and inquired with an arched brow how long he had been divorced—as if the need for companionship might be the real motive behind his visit! He felt certain that on more than one encounter with the gargantuan and supremely disengaged mother, that he had smelled alcohol on her breath, cheap wine, if he had to hazard a guess.

But what now, he wondered? Usually, Mariel crept about in a surprisingly stealthy manner for such a large girl, but now she commanded the street like a general, silent but for the grating bell that even now rang out demandingly once more…but for what?

Forgetting the carpet cleaner, he set down his morning mug and glided stealthily back to his observation point at the window. He felt trapped, somehow, by this sly little giant so inappropriately named ‘Mariel’. What had her mother been thinking, he asked himself with a shake of his graying head, to assign this clumsy-looking creature such a delicate, feminine name? When he peeked out again it was to find Mariel’s bike lying discarded on his lawn, the girl nowhere to be seen. The crease between his eyes became a furrow and he rushed through his silent house to the kitchen windows.

Carefully parting a slat of his Venetian blinds, he looked on the path that led between his property and the next and on into the woods, a large head of curly hair was just disappearing down it and into the trees. A shudder ran through his body and beads of sweat formed above his upper lip like dew. ‘Damn the girl,’ he thought, feeling slightly nauseous as suspicion uncoiled itself within his now-queasy guts.

Unbidden, the image of the dog trotted into his mind, its hideous prize clasped between its slavering jaws. It had reeked of the rancid earth exposed by the recent torrential rains. He remembered with a shudder of distaste and a rising, renewable fury how it had danced back and forth across his sodden lawn, clearly enjoying its game of ‘keep away’. He remembered the shovel most of all, its heft and reach, the satisfaction of its use.

“That was her dog,” he breathed into the silent, waiting room, then thought, ‘Of course it was…it would be.’ His soft hands flexed as if gripping the shovel once more.

Mariel stood over the shallow, hastily dug grave and contemplated the partially exposed paw. The limb showed cinnamon-colored fur with black, tigerish stripes that she immediately recognized. She hadn’t really cared for Ripper, (a name he had been awarded as a puppy denoting his penchant for ripping any and every thing he could seize between his formidable jaws) but he had been, ostensibly, her dog.

Ostensibly, because as he had grown larger, his destructive capabilities, coupled with Mariel and her mother’s complete disregard of attempting to instill anything remotely resembling discipline, had resulted in a rather dangerous beast that had to be kept penned in the back yard at all times. Mariel had served largely as Ripper’s jailer.

As she couldn’t really share any affection with the dog, or he with her, they had gradually grown to regard one another with a resigned antipathy, if not outright hostility—after all, she was also the provider of his daily meals which she mostly remembered to deliver. It was also she that managed to locate him on those occasions when he found the gate to his pen unlatched (Mariel did this from time to time to see what might happen in the neighborhood as a result) and coaxed him into returning. This was the mission in which Mariel had been engaged this Saturday morning in early November. She saw now that she had been only partially successful, Ripper would not be retuning to his pen.

Looking about for something to scrape the loose earth off her dog’s remains, she pried a rotting piece of wood from a long-fallen pine tree and began to dig into the damp, sandy soil. Grunting and sweating with the effort, her Medusa-like curls bouncing on her large, round skull, Ripper was exposed within minutes. Whoever had buried him had not done a very good job of it and the slight stench of dead dog that had first led her to the secret grave rose like an accusing, invisible wraith. Mariel wrinkled her stubby nose.

Ignoring the dirt and damage being done her purplish sweat shirt and pants that matched her bicycle, she seized the dead creature by his hindquarters and dragged him free of the grave. Letting him drop onto the leaf litter of the forest floor with a sad thump she surveyed her once-fierce companion.

She thought that he looked as if the air had been let out of him—deflated. His great fangs were exposed in a permanent snarl or grimace, the teeth and eyes clotted with earth. She pushed at his ribcage with a toe of her dirty sneaker as if this might goad him back into action, but nothing happened, he just lay there.

She thought his skull appeared changed and squatted next to him to make a closer examination. As she brought her large face closer, the rancid odor grew stronger yet, but Mariel was not squeamish and so continued her careful scrutiny. It was different, she decided. The concavity that naturally ran between Ripper’s eyes to the crown of his skull was now more of a valley, or canyon. Mariel ran a finger along it and came away with a sticky black substance clinging to it. The stain smelled of death and iron.

Having completed her necropsy, Mariel stood once more and surveyed the surrounding woods. The trees had been largely stripped of their colorful foliage by the recent nor’easter, but her enemy was not to be seen. Though she did not truly mourn Ripper’s untimely passing, she did greatly resent the theft of her property and its misuse, and concluded with a hot finality that someone owed her a dog.

She gently kicked Ripper’s poor carcass as a final farewell then turned to leave and find a wheel barrow in which to transport him home once more. She knew of several neighbors who possessed such a conveyance and almost none were locked away this time of year.

It was then that something within the dog’s recent grave caught her attention—something that twinkled like a cat’s eye in the slanted beams of daylight that filtered through the trees. Mariel dropped to her knees, thrusting her chubby hand into the fetid earth to retrieve whatever treasure lay within. When she withdrew it once more it was to find that she clasped a prize far greater than any she could ever have imagined—a gold necklace, it’s flattened, supple links glistening like snake skin and bearing a pendant that sparkled with a blue fire in the rays of the milky sun. Mariel had no idea as to what, exactly, she had discovered, but her forager’s instinct assured her that she clasped a prize worth having.

Without hesitation, she gave it a tug to free it from the grasp of Ripper’s grave, but oddly, found that her efforts were resisted. She snatched at it once more, impatient to be in full possession of her prize, and felt something beneath the dirt move and begin to give way. Encouraged at the results of this tug-o-war, she seized the links in both hands now and rocked back on her considerable haunches for additional leverage.

With the dry snap of a breaking branch, the necklace came free and Mariel found herself in full possession. The erupted earth, however, now revealed a yellowish set of teeth still lodged in the lower jawbone of their owner. Several of these teeth had been filled with silver and as Mariel had also been the recipient of such dental work, she understood that the remains were those of a human. A stack of vertebrae were visible jutting out from the dirt, evidence of the result of the uneven struggle, though the remainder of the skull still lay secure beneath the soil.

Mariel’s grip on the pendant never wavered as she regarded the neck of the now-headless horror that had previously worn the coveted necklace. With only a slight “Ewww,” of disgust, she rose in triumph to slip the prized chain over her own large head, admiring the lustrous sapphire that hung almost to her exposed navel while ignoring the slight tang of death that clung to it. She felt well-pleased with the day’s outcome, Ripper’s demise notwithstanding.

With her plans now altered by this surprising acquisition, Mariel dragged her dog’s much abused corpus back to the grave from which she had only just liberated him, tipped him in and began to cover Ripper and his companion once more. When she was done, she studied the results for several moments; then thought to drag a few fallen branches over her handiwork.

Satisfied with the results, she turned for home once more, pausing only long enough to slip the necklace beneath her stained sweat shirt. Mariel did not want to have to surrender her hard-won treasure to her mother, who would undoubtedly covet the prize and seize it for her own adornment. Besides, she had things she wanted to think about and did not want anyone to know of the necklace until the moment of her choosing, specially, the three men who occupied the homes on the cul-de-sac. It had not escaped Mariel’s notice that only those three had easy access to the path that led into the woods and passed within yards of the secret grave.

The neighbor watched her emerge from the trees and march past his house. He studied her closely but could read nothing from her usual closed expression. Other than her clothes being a little dirtier than when she went in she appeared the same as always and he breathed a sigh of relief.

It was silly, he thought as he saw her raise and clumsily mount her bike, how one unpleasant child could instill so much unease. It was because he was a sensitive man, he consoled himself—he had been a sensitive boy and with adulthood nothing had really changed. He had always resented the unfeeling bullies of the world, child or adult. Children like Mariel had terrified him when he had been a school boy and apparently nothing had changed in that respect either.

The sudden jangling of the bell caused him to gasp and his eyes returned to the robust figure of Mariel. She surveyed the surrounding houses with her implacable gaze, studying each of the three on the cul-de-sac in turn, coming at last back to his own. He shrank back from the window once more, his heart beating rapidly.

Then, with a thrust of a large thigh, her bike was set in motion and she pedaled from his sight with powerful strokes. “Damn her”, he whispered defiantly as his earlier concerns returned with such force that his blood suddenly roared within his ears.

Finding an overstuffed chair to settle into, he peered around the plush, dim room with its collection of his own paintings on the wall, while around him song birds began to chirp and sing from their cages as if to restore and calm him. He smiled weakly in gratitude at their effort even as Mariel’s imperious face returned to his mind’s eye with a terrible clarity. He closed his eyes against her, massaging his now-throbbing temples with his soft fingertips. If she had discovered anything in those woods, he asked himself, she would have come out screaming, wouldn’t she? He lowered his head into his sweaty hands, while a blood-red image of Mariel shimmered on his inner eyelids …wouldn’t she?

Mariel had no trouble engineering her encounter with Mister Salter. He worked on his lawn from early spring until the cold and snow of January finally drove him indoors. As long as there was any light she knew that her chances were good of finding him in his yard. So after she was delivered home by her school bus and enjoyed a snack of cream-filled cupcakes she pedaled her bike directly to the cul-de-sac and his property.

Salter watched her approach with a sour expression meant to ward her away, but Mariel was not troubled by such subtleties. She came to a sudden halt in his driveway causing a scattering of carefully raked gravel. She watched Salter’s expression darken at this, but he refrained from saying anything. He shut off the leaf blower he had been using and its piercing whine faded away. Man and girl observed each other from several yards apart as his corpulent Labrador waddled happily toward Mariel, thick tail wagging.

“Bruiser,” Salter warned menacingly.

The dog ignored him and continued on to Mariel, pleased to be patted on his large head. Salter’s complexion went darker yet.

“Can I do something for you?” he asked, his tone clearly inferring the opposite.

Mariel regarded him without answering, while fingering the necklace she had retrieved from its hiding place before going out. Salter fidgeted beneath her round-eyed stare. “Be careful of the dog,” he muttered hopefully, “he might bite.”

As Mariel had surreptitiously recruited Salter’s dog during her many secret forays, she knew this to be untrue. She often went into Salter’s garage where he kept the dog food and fed the animal while he was away teaching shop at the high school, Bruiser was always pleased to see her as a result. As if to emphasize their relationship, the dog laid its great head on her thigh, sighed, and stared adoringly into her eyes.

This was too much for Salter, who turned his wide back on her and went to pull at the cord that would start his treasured leaf-blower.

Mariel glanced at the well-worn path that led from Salter’s back yard and into the woods. “I have this,” she said, pulling the necklace from her shirt and allowing it to fall down over her plump stomach. The sapphire shone in the late day sun like a blue flame. Her eyes remained warily on Salter, even as her small mouth puckered into a smile of possessiveness.

Salter, glancing over his shoulder, halted, and turned slowly back. “Where the devil did you get that?” he managed. He took a few steps closer as Mariel backed her bike away an equal distance. Bruiser’s head slid off her thigh leaving a trail of saliva.

Seeing this, Salter stopped and studied Mariel’s prize from where he stood. “Did your mother say you could wear that?” he asked.

As the girl did not reply, but only continued her unsettling scrutiny, he added, “Does she even know that you have it? For that matter, how the hell could your mom afford something like that…provided its real, of course?” Forgetting himself, he took another few steps, but Mariel was already turning her bike to coast down his driveway.

“I know that you’ve been coming onto my property,” he called to her as she picked up speed with each stroke of her powerful legs. “You’d better stop sneaking around here…it’s called trespassing you know, I could call the cops.” His voice grew louder as she added distance between them. “And maybe I will the next time,” he offered.

“Did you steal that?” he called out meanly as she disappeared around the curve.

Mariel only looked back as she sped up the street and out of sight of the cu-de-sac. A small smile played on her puckered lips. She scratched Mr. Salter off her list of suspects.

Mariel surprised Mister Forster in his own back yard. She had glided silently across his still-green lawn to roll to a halt at the back edge of his house. Forster had his back to her and was busily feeding and talking to his flock of tiny bantam hens. He did not notice her arrival. The hens themselves restlessly pecked and grumbled within the pen he had provided them and gave her no notice as Forster continued to scatter feed amongst them.

Mariel enjoyed watching these birds, and had several times in the past attempted to better make their acquaintance. On one such occasion, Forster had found Mariel within the pen itself attempting to catch one of his miniature chickens, feathers flying about in the air amid a cacophony of terrified squawking. He had been livid with rage at her incursion and had joined the ranks of other neighbors who had visited her home to complain to her mother. Mariel had learned to be more careful since that encounter and had not been caught since, but neither had she been successful.

“They’re funny,” Mariel lisped quietly.

Forster spun around scattering the remainder of the feed from the bowl he was using. “Oh,” he cried, as the small, black fowl swarmed his shoes and cuffs for the errant seeds. “Oh,” he repeated; then focused on his unexpected visitor. He brought a hand up to his heart and gasped, “You scared me half to death, Mariel. I didn’t hear you come up and you nearly scared me half to…” he caught himself. “You usually ring that little bell of yours,” he finished with a limp gesture at her bike.

Man and girl regarded one another across several yards of mostly grassless, churned-up soil…evidence of poultry. A worn path into the woods separated them. Mr. Forster set the metal bowl down and opened the pen door to come out. Mariel clumsily rolled her bike into a half-circle that left her facing in the direction from which she had come.

The older man appeared to note the child’s wariness and slowed his steps, easing himself leisurely through the door and taking his time in carefully closing and latching the wire-covered frame. When he turned once more to Mariel it was to find her holding out a large jewel pendant that hung about her neck from a gold-colored chain. She reminded him of the vampire-slayers in horror films attempting to paralyze and kill their undead foes with a crucifix.

“My goodness, Mariel that is some necklace you have there. It’s lovely. You are a very lucky girl to have that.”

Mariel continued to fix him with both her gaze and the pendant while her lips vanished into a grim, pensive line. Forster stared back uncertainly. “Was there something that you wanted?” he thought to ask at last.

The sapphire wavered in her grip and she slowly lowered and slipped it once more beneath her top. It appeared to have no power over this man either. As she puzzled over her lack of progress in her investigations thus far, Forster took two steps closer.

Forster was only slightly taller than Mariel and had no more than fifteen pounds over the ten-year-old, so she was not as intimidated as she might have been with other men in the neighborhood.

“It’s the hens, isn’t it?” he ventured. “You appreciate them like I do.” He glanced back over his shoulder at the chicken coop. “I was probably a little hasty last time you were here,” he continued. “I should have thought…but when I heard all that commotion and came out to find someone in the pen…Well, I should have realized that you were just as fascinated by them as I am.” He studied Mariel’s broad, unintelligent face for several moments. “Would you like to hold one?”

Mariel’s gaze flickered just slightly at this invitation. The thought of actually holding one of the softly feathered birds had become something of a Holy Grail for her and her breath caught at the idea.

Forster turned and retraced his steps to the coop and within moments returned stroking a quietly clucking hen. Mariel smiled and reached out both arms for the coveted bird, but Forster stopped a few paces short of her. Still running his hand over the bantam’s glossy feathers, he nodded contentedly at Mariel, and said, “Show me that necklace again, why don’t you? I was too far away to be able to see it well. How about another look…I won’t touch it; then I’ll let you hold Becky.” He smiled widely at Mariel and held the bird a few inches away from his chest to indicate his willingness.

Mariel quickly retrieved the necklace from within her shirt and held out the pendant for him to study, her small greedy eyes never leaving the near-dozing hen. Forster leaned forward onto the balls of his feet and studied the stone silently for several moments. Finally, Mariel heard him exhale and murmur, “You should be very careful with that, Mariel. That’s exactly the kind of thing that grown-ups will want to take from you.” He leaned just a little closer and asked, “Does your mother know you’ve got that?” And when she fidgeted and didn’t answer right away, added, “I wouldn’t tell her, if I were you…she’ll want to wear it…and keep it…for sure. Any woman would.”

Mariel stuffed the necklace back down her shirt and thrust her arms out once more for the agreed-upon chicken. Forster carefully placed it within her thick arms and smiled as Mariel’s normally glum face began to light up with the tactile pleasure of the silken bird. In her enthusiasm, she began to run her sticky hand down the hen’s back with rapid movements, even as ‘Becky’ began to squirm and protest volubly at the excessive downward pressure of her strokes. The contented clucking quickly became the frenzied cackles of a terrified chicken in the clutch of a bear cub.

Forster, seeing that Mariel’s technique required more practice and refinement, made to take the bird from the grinning school girl, but she turned away with her prize as if she meant to keep Becky at all costs. With that movement, however, the hen was given just the opening she required in which to free her wings. Becky began to flap them frantically in her rapidly escalating desire for freedom.

Startled, Mariel released the bird, which in a whirlwind of beating wings and flying feathers covered the short distance to her coop in awkward bounds only slightly resembling actual flight. Mariel was left with nothing but a few of the errant feathers and her hot disappointment.

With a frown of both disapproval and resentment, she pushed off on her bike and made for Crumpler Lane. Behind her, Forster called out, “They just take a little getting used to, Mariel. Come back when you want and I’ll teach you to handle them!”

After she had gone away, he turned to his precious coop to insure that Becky was returned and properly locked in for the night. Then, with a sigh, went up the back steps and into his house, turning on the lights in room after room as true darkness fell.

Mister Wanderlei was next on Mariel’s’ list and she was not long in cornering him. She found him that very Saturday as he was painting the wooden railing of his front porch.

Stopping at his mail box, she gave her bike bell several sharp rings to gain his attention. He glanced over his shoulder and smiled at her.

“Hello, Mariel,” he called, while lifting a paint brush in salute. “Another few weeks and it will be too cold to do this.”

Mariel could think of nothing to reply and so rung her bell once more. Mister Wanderlei set the brush carefully on the lip of the can and stood, wiping his hands on the old corduroy pants that he was wearing. “Is that a new bike?” he asked amiably.

Mariel nodded her big head at this, then thought to add, “My Grandma bought it for me…I didn’t steal it.”

Wanderlei smiled and answered, “I never would have thought so.” He ambled down the steps in her direction.

Mariel fumbled with the necklace and only just managed it bring it out from beneath her top as he drew near. This caused Wanderlei to halt for a moment as he took in Mariel’s rather astounding adornment.

“Goodness,” he breathed at last. “That’s some necklace for a little girl. Where did you get that?” He ran a large knuckled hand across the top of his mostly hairless skull.

As she had done with Salter and Forster, Mariel realigned her bicycle for a quick escape should it prove advisable, one foot poised on a pedal. She remained silent.

Wanderlei fished a handkerchief from his pocket and set about wiping his face and near-naked pate. “Such things cause great temptation,” he said finally. “Of course, I know that you’re too young to understand what I mean exactly.” He glanced up and down the street; then turned his gaze onto her once more.

“Where I work, there are men who have killed for such baubles.” A slight frown crossed his face. “Do you know where I work, Mariel?”

In fact, Mariel did know, as one of her uncles had pointed him out to her during a visit between incarcerations. She nodded slightly.

Wanderlei studied her face with interest, then said, “Well, then you know that I’ve spent my life amongst a lot of very bad people.” His eyes had taken on a sparkle that was beginning to make Mariel uneasy. He took another step and she eased her rump upwards in preparation for escape.

“Are you Christian?” he asked gently. “Does your mother ever take you to church?”

Mariel frowned, unable to follow Mr. Wanderlei’s drift. Even so, she nodded involuntarily out of nervousness.

“Is that right?” he smiled, completely ignoring her necklace. “Really, what church would that be?”

“We go sometimes,” Mariel whispered, for some reason not wanting to lie outright to this man. “We’re Cat’lics.”

Wanderlei’s expression became one of disappointment. “Oh, I see,” he murmured. “That would explain the love of gold and baubles,” he said quietly, as if Mariel were no longer there.

Mariel rose up and pushed down on the waiting pedal, she had learned what she needed to know here.

Wanderlei looked up as she pulled away, his expression gone a little wistful now. “You and your mother are welcome to attend the services here at our house anytime that you want,” he called after her. “God accepts anyone that has an open heart. Do you have an open heart, Mariel?”

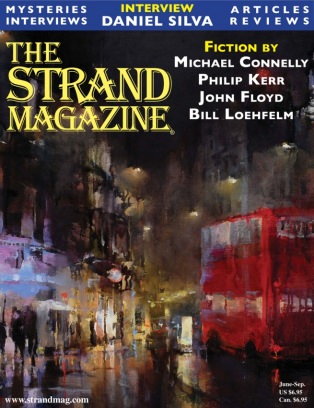

Much of my recent run of good fortune seems to be linked to the folks at The Strand Magazine. (I've written about that publication in two previous SleuthSayers columns: "Stranded" in November 2011 and "Stranded Again" in July 2014. Which led to the brilliantly original title of this piece.)

Much of my recent run of good fortune seems to be linked to the folks at The Strand Magazine. (I've written about that publication in two previous SleuthSayers columns: "Stranded" in November 2011 and "Stranded Again" in July 2014. Which led to the brilliantly original title of this piece.) The third good thing happened almost a month later, on February 19. I received an e-mail from Otto Penzler in New York, informing me that he and guest editor James Patterson had selected one of my stories, "Molly's Plan," for inclusion in The Best American Mystery Stories 2015, to be published this October. (That story was also from the Strand--their June-September 2014 issue.) I've been buying and reading the annual BAMS anthology for years, and although I've been fortunate enough to be shortlisted several times I'd never before made it into the book.

The third good thing happened almost a month later, on February 19. I received an e-mail from Otto Penzler in New York, informing me that he and guest editor James Patterson had selected one of my stories, "Molly's Plan," for inclusion in The Best American Mystery Stories 2015, to be published this October. (That story was also from the Strand--their June-September 2014 issue.) I've been buying and reading the annual BAMS anthology for years, and although I've been fortunate enough to be shortlisted several times I'd never before made it into the book.