11 January 2014

Bingeing on TV Series

by Elizabeth Zelvin

Thanks to the October-November 2013 issue of the AARP magazine, I've learned that there's a name for something I've been doing for the past year or so, since I got an iPad and a flat-screen computer and joined Netflix and Hulu Plus: binge watching. According to AARP, it's even age-appropriate. I'm taking advantage of my access to old as well as current TV series to watch consecutive episodes of series that I loved and some that I missed, not to mention catching up with series that are still running that I've heard about but haven't had a chance to try.

The author of the AARP article cites a media psychology expert, saying "she sees binge watching as empowering: It allows viewers to watch TV the way they might read a book." As it happens, I am an expert on addictions and compulsive behavioral disorders myself, and I try not to cross the line with any pleasurable activity. Not being perfect, I occasionally risk a headache to watch one more episode instead of quitting while I'm ahead--the equivalent to staying up till 3 AM to finish a suspenseful novel. But by and large, it is like reading a book: once I'm drawn into the story, I want to keep going, and I stop noticing how much time is passing.

As with books, my tastes are idiosyncratic. A certain percentage of my favorite shows are British crime series, some based on novels that I read and loved, some not. Some are American--fewer crime series, as I don't like the graphic gore in many shows, but there are some wonderful legal and political dramas. I like well-acted, well-written period pieces. And I'm always curious about shows that speak to my other particular interests, such as recovery and country music. I'm less likely to watch a show whose protagonist is an active alcoholic or drug addict with no recovery in sight (bor-ing!). I prefer the commercial-free Netflix streaming or DVDs, or those on HBO and PBS (both have free apps), to Hulu, which has commercials, but I'll put up with them for the sake of a series (or past seasons) I can't get otherwise. I do draw the line at laugh tracks, which bump me right out of the story.

Here are some of the crime shows that I've watched so far:

Inspector Morse: Oxford beautifully photographed, murders intelligently solved. Morse is my exception to the rule about active alcoholics. The byplay between Morse and Sergeant Lewis is delicious. Inspector Lewis: Even better! For a while, I alternated episodes of Morse and Lewis for the fun of seeing Kevin Whately age and become young again every evening. Prime Suspect: Nice to see Helen Mirren at the beginning of her ongoing prime, and I'd never seen the later episodes.

Midsomer Murders: Based on Caroline Graham's Inspector Barnaby books. The twenty-two seasons featuring John Nettles as Barnaby ring endlessly inventive changes on the British village mystery: Drop-dead charming villages, stately homes, gorgeous gardens, and a seething mass of malice and all the deadly sins beneath the surface. I recently learned there's a new DVD of Season 23, when Barnaby's retired and his cousin John takes over. I'm hoping it will soon appear on Netflix.

Dalziel & Pascoe: Based on the late Reginald Hill's brilliant books. After the first few seasons, the show went off in its own direction, divorcing Pascoe's feminist wife Ellie and making up its own mysteries instead of using the exceedingly brainy later books or delving more deeply into Sergeant Wield's love life. Netflix has it on DVD only, and Seasons 7 and 8 are not yet available.

Monk: Tony Shalhoub is brilliant as the obsessive compulsive detective, and San Francisco has never looked better. I had seen the first few seasons with Sharona but not the later ones with Natalie as Monk's assistant. I spot a lot of the clues much too early, but that's happening to me with novels too--the down side of being a mystery writer myself.

Sherlock: The present-day version with Benedict Cumberbatch as a Holmes who manages to be appealing in spite of having a lot more brain than heart and Martin Freeman, looking just a little like a hobbit, as a blogging Watson who has recently returned from, yep, Afghanistan. The first two seasons had only three episodes each, but they were doozies. Season 3 starts this month, and I can hardly wait.

To be continued in a future post.

10 January 2014

Interesting Rejections

by Dixon Hill

OR: If at first you don’t succeed…

Well, the holidays are over and we’re rapidly approaching that time when writers can, once again, open their mailboxes hoping to find responses from agents and editors.

We all hope for acceptances. But, we all know there will undoubtedly also be rejections.

John Floyd’s excellent post about rejections, on January 4th, evoked so many thoughts in my mind, I suffered a mental log-jam. I finally realized I’d be better off posting some of them as an article, instead of as a comment.

Over time, I realized this article may probably be better suited to newer writers, because my thoughts are not really about how to handle the standard multi-xeroxed rejection letter a writer usually receives, but rather how to handle rejection letters that name names (or wish to!) and get specific. The more experienced writer, however, may wish to continue reading to get a kick out of foolish things I’ve done. (It won’t hurt my feelings.) And, though I’m usually long-winded, today I’ll include only three examples.

Example 1

The first rejection I ever received was for my very first fiction submission, which I wrote on an electric typewriter while still in the army. I got a very nice hand-written letter from the fiction editor at Omni magazine, saying the piece wasn't right for their publication. She then went on to praise my writing, adding that she hoped I’d send more stories in the future.

The editor was correct; the story wasn't right for Omni — it narrated the death of a young boy murdered by a satanic elevator in a post-nuclear-holocaust world. I should have sent it somewhere else, which is what that editor suggested. I, however, knew nothing about fiction markets and had no idea where else I might send it.

My biggest mistake, of course, is that I thought the editor was “just being nice.” So, I tore up the manuscript and her letter (after reading her praise several times), then burned them in my fireplace, thinking I just wasn’t cut out to be a writer. Nearly a decade passed before I submitted another fiction story.

(While the experienced writers go dispose of the clumps of hair they just pulled from their scalps, I’d like to take a moment to address newer writers, then we’ll move on to the next two examples.)

Newer writers should be advised: Editors don’t send hand-written letters praising your work just to be nice. They’re far too busy. If you ever get a rejection like this:

2. Visit the website of the magazine that rejected you so kindly, and read their Writer Guidelines, then write a story that falls within those guidelines. There’s a very good chance they’ll buy it! After all, the fiction editor likes the way you write.

Example 2

I once submitted a speculative fiction piece and received a short note on my form rejection letter, which read: “Next time PLEASE GIVE YOUR MAIN CHARACTER A NAME!”

A friend who saw this was very taken aback. She said, “Wow! That’s harsh!”

I told her, “Hey, at least I know what they didn’t like about it. Some magazines don’t mind printing stories with unnamed protagonists. Now, however, I know this one doesn’t like it.”

I consider such information to be quite valuable.

Example 3

I once wrote a story that concerned me quite a bit.

The thing that bothered me was: men who read it tended to like it, but almost every woman who read it hated the thing. I had a pretty good idea why this was, but didn't feel I could do anything about it, because it was a central aspect of the story: remove the problem-causing aspect, and the story disappeared.

Finally, deciding “Nothing ventured, nothing gained!” I shipped it off.

The rejection was very useful. The editor said she was sure I’d be able to find a venue which would publish the story. I can’t remember the precise words of the letter, but she then added something pretty close to:

Strong words.

But, honest.

And, very useful. I’d been worried that women didn’t like the story. The editor’s response convinced me: This may be a powerful story — it certainly provoked powerful reactions from more than just the editor — but…

As a writer who’s still trying to build his name, I have no desire to alienate female readers who might confuse the protagonist’s voice (the story was first person) with mine. Consequently, instead of trying to sell this piece elsewhere, I keep it in my computer’s memory bank.

Perhaps, one day, if I ever gain a large following, I can afford to let it see the light of day. But, for now, I think I’ll sit on it and try not to alienate one of the only two genders on the planet.

See you in two weeks!

--Dixon

Well, the holidays are over and we’re rapidly approaching that time when writers can, once again, open their mailboxes hoping to find responses from agents and editors.

We all hope for acceptances. But, we all know there will undoubtedly also be rejections.

John Floyd’s excellent post about rejections, on January 4th, evoked so many thoughts in my mind, I suffered a mental log-jam. I finally realized I’d be better off posting some of them as an article, instead of as a comment.

Over time, I realized this article may probably be better suited to newer writers, because my thoughts are not really about how to handle the standard multi-xeroxed rejection letter a writer usually receives, but rather how to handle rejection letters that name names (or wish to!) and get specific. The more experienced writer, however, may wish to continue reading to get a kick out of foolish things I’ve done. (It won’t hurt my feelings.) And, though I’m usually long-winded, today I’ll include only three examples.

|

| I love the last clause on this sign. It just seems so appropriate. |

Example 1

The first rejection I ever received was for my very first fiction submission, which I wrote on an electric typewriter while still in the army. I got a very nice hand-written letter from the fiction editor at Omni magazine, saying the piece wasn't right for their publication. She then went on to praise my writing, adding that she hoped I’d send more stories in the future.

The editor was correct; the story wasn't right for Omni — it narrated the death of a young boy murdered by a satanic elevator in a post-nuclear-holocaust world. I should have sent it somewhere else, which is what that editor suggested. I, however, knew nothing about fiction markets and had no idea where else I might send it.

My biggest mistake, of course, is that I thought the editor was “just being nice.” So, I tore up the manuscript and her letter (after reading her praise several times), then burned them in my fireplace, thinking I just wasn’t cut out to be a writer. Nearly a decade passed before I submitted another fiction story.

(While the experienced writers go dispose of the clumps of hair they just pulled from their scalps, I’d like to take a moment to address newer writers, then we’ll move on to the next two examples.)

Newer writers should be advised: Editors don’t send hand-written letters praising your work just to be nice. They’re far too busy. If you ever get a rejection like this:

1. Do NOT destroy your manuscript! The editor actually liked it. A lot! Somebody else will almost surely buy it; you just have to find the right publication.

2. Visit the website of the magazine that rejected you so kindly, and read their Writer Guidelines, then write a story that falls within those guidelines. There’s a very good chance they’ll buy it! After all, the fiction editor likes the way you write.

I once submitted a speculative fiction piece and received a short note on my form rejection letter, which read: “Next time PLEASE GIVE YOUR MAIN CHARACTER A NAME!”

A friend who saw this was very taken aback. She said, “Wow! That’s harsh!”

I told her, “Hey, at least I know what they didn’t like about it. Some magazines don’t mind printing stories with unnamed protagonists. Now, however, I know this one doesn’t like it.”

I consider such information to be quite valuable.

Example 3

I once wrote a story that concerned me quite a bit.

The thing that bothered me was: men who read it tended to like it, but almost every woman who read it hated the thing. I had a pretty good idea why this was, but didn't feel I could do anything about it, because it was a central aspect of the story: remove the problem-causing aspect, and the story disappeared.

Finally, deciding “Nothing ventured, nothing gained!” I shipped it off.

The rejection was very useful. The editor said she was sure I’d be able to find a venue which would publish the story. I can’t remember the precise words of the letter, but she then added something pretty close to:

“Please never send us anything written in this voice ever again.”

Strong words.

But, honest.

And, very useful. I’d been worried that women didn’t like the story. The editor’s response convinced me: This may be a powerful story — it certainly provoked powerful reactions from more than just the editor — but…

As a writer who’s still trying to build his name, I have no desire to alienate female readers who might confuse the protagonist’s voice (the story was first person) with mine. Consequently, instead of trying to sell this piece elsewhere, I keep it in my computer’s memory bank.

Perhaps, one day, if I ever gain a large following, I can afford to let it see the light of day. But, for now, I think I’ll sit on it and try not to alienate one of the only two genders on the planet.

See you in two weeks!

--Dixon

09 January 2014

Beginnings

|

| Keats' death mask, not mine. I think mine got lost in the mail. |

The past few months have given me a renewed appreciation for the great English poet John Keats ("Endymion," "Ode on a Grecian Urn," etc.).

For those of you not familiar with the gentleman in question, he wrote a ton of poetry and published a significant amount of that before his untimely death from tuberculosis at the ripe old age of 25 in 1821.

Me?

Not as much.

And I'm nearly twice his age.

Keats' accomplishments are rendered all the more remarkable in my mind by the knowledge that he did most of his best work while dying of tuberculosis. Tuberculosis cut a wide swath through his family, taking his mother and a brother he himself nursed while afflicted with the disease.

Me?

I've been fighting a non-lethal, yet chronic lung ailment since mid-September.

My writing output during that time has been pretty much nil.

Now, as I said, I don't have tuberculosis. What I've got isn't fatal. It's nagging and drags me down and wears me out, as few things (aside from fatherhood or standing underway watches in the navy) have, but it's not killing me. That said, it sure did destroy my momentum on my latest writing project.

And that makes me wonder just how the hell Keats did it.

Granted, he didn't have a marriage and a toddler and a career (he never used the medical degree he earned). But based upon my own limited and humbling experience with this sort of thing, I can't conceive how anyone chronically ill and distracted by poor health could clear the headspace to create the sort of art that Keats did.

I have been losing that battle for months and it's only recently that I've begun to be able to wrap my head around the plot problems in my current novel that need addressing before I can move on out of my months-long stall.

So how the hell did Keats do it?

(Let's not limit it to Keats. He's just one example. There are many others in the world of arts and letters)

I ask because I'm taking advantage of the cyclical artificial "beginning" offered by the new calendar year to both recommit to this project, and ask: what are your goals this year, writing-wise?

Mine? Finish my stalled novel, finish three short stories in varying stages of drafting, and start on my next full writing project.

And all before my kid turns three!

What so you all?

Goals?

Thoughts on pushing through distraction and knuckling down in true Keatsian fashion?

08 January 2014

Post-Partum

I wrapped the rough draft of a thriller called EXIT WOUNDS yesterday. The start date was 07-13-13, so about six months to write. It clocks in at 60K words, which is quick and dirty compared to the two previous books, both of which ran to 100K, and took longer. The more curious thing is that although it gives me an enormous sense of satisfaction, I'm feeling somewhat bereft, or adrift.

My general habit is that after I finish a book, I'll buckle down to some short stories, and I try to hit a deadline of a week to ten days for each story. David Morrell is fond of quoting Carrie Fisher, "The problem with instant gratification is that it isn't quick enough." The difference between a story and a novel isn't simply word count, but stamina. A short story is like sudden, fugitive sex. A novel is a relationship.

Writing a book, you're waking up with the same person every morning, and some days they're happier to see you than others. You're familiar with their contours, even if you sometimes wonder what possibly prompted you to fall in love with them in the first place.

I don't know about you, but I need to have a project of some kind going all the time. I like doing stories, because you do get that quick, energizing, empowering hit, and you know right away whether you got it right. Still, a book, where you're in it for the long haul, has a rhythm, and a kind of tidal pull, because you're navigating deeper waters, and uncharted shoals, often without a compass, what might be called dead reckoning.

A short story may come to you fully-fleshed, and all of a piece. A novel doesn't, in my experience. You may try on every piece of clothing in your wardrobe, until you find the one that fits. And there's a lot of second-guessing. Did you start down a blind alley, with no exit strategy? Or is such-and-such a scene proving impossible to write, simply because it's in the wrong book? On the other hand, the most intractable issue can suddenly resolve itself, when you hold it up to the light. You never know. The struggle is part of the gain. This, of course, is exactly why I'm feeling this let-down. The process is consuming, and exhausting, and at the same time, exhilarating, and then you run out of road.

The other part, obviously, is that it may not turn out to be the book you meant to write. There's the observation Auden or Berryman or one of those guys made, that a novel is a prose work of a certain length that has something wrong with it. This is maybe more true of a literary novel than a genre one, but it still applies. We see the soft spots, inconsistency or structural weakness, the easy choices and cheap effects. I have a friend who says he won't go back and read his older stuff, he's afraid it will make him cringe.

We set the bar higher with every book or story. We're less willing to settle for watered wine. We all have a bag of tricks, whether it's wisecracking dialogue or evocative physical description or heart-stopping violence, but as we mature (I mean in the sense of sharpened skills), it's no longer as simple as having a guy come through the door with a gun. Not that some devices aren't tried-and-true, but we're not as likely to use them reflexively. We rehearse the play longer, we take greater care to hit our marks, and we hope opening night sells out to standing room only.

With that said, on to the next sordid affair.

My general habit is that after I finish a book, I'll buckle down to some short stories, and I try to hit a deadline of a week to ten days for each story. David Morrell is fond of quoting Carrie Fisher, "The problem with instant gratification is that it isn't quick enough." The difference between a story and a novel isn't simply word count, but stamina. A short story is like sudden, fugitive sex. A novel is a relationship.

Writing a book, you're waking up with the same person every morning, and some days they're happier to see you than others. You're familiar with their contours, even if you sometimes wonder what possibly prompted you to fall in love with them in the first place.

I don't know about you, but I need to have a project of some kind going all the time. I like doing stories, because you do get that quick, energizing, empowering hit, and you know right away whether you got it right. Still, a book, where you're in it for the long haul, has a rhythm, and a kind of tidal pull, because you're navigating deeper waters, and uncharted shoals, often without a compass, what might be called dead reckoning.

A short story may come to you fully-fleshed, and all of a piece. A novel doesn't, in my experience. You may try on every piece of clothing in your wardrobe, until you find the one that fits. And there's a lot of second-guessing. Did you start down a blind alley, with no exit strategy? Or is such-and-such a scene proving impossible to write, simply because it's in the wrong book? On the other hand, the most intractable issue can suddenly resolve itself, when you hold it up to the light. You never know. The struggle is part of the gain. This, of course, is exactly why I'm feeling this let-down. The process is consuming, and exhausting, and at the same time, exhilarating, and then you run out of road.

The other part, obviously, is that it may not turn out to be the book you meant to write. There's the observation Auden or Berryman or one of those guys made, that a novel is a prose work of a certain length that has something wrong with it. This is maybe more true of a literary novel than a genre one, but it still applies. We see the soft spots, inconsistency or structural weakness, the easy choices and cheap effects. I have a friend who says he won't go back and read his older stuff, he's afraid it will make him cringe.

We set the bar higher with every book or story. We're less willing to settle for watered wine. We all have a bag of tricks, whether it's wisecracking dialogue or evocative physical description or heart-stopping violence, but as we mature (I mean in the sense of sharpened skills), it's no longer as simple as having a guy come through the door with a gun. Not that some devices aren't tried-and-true, but we're not as likely to use them reflexively. We rehearse the play longer, we take greater care to hit our marks, and we hope opening night sells out to standing room only.

With that said, on to the next sordid affair.

Labels:

David Edgerley Gates,

novels,

short stories

Location:

Santa Fe, NM, USA

07 January 2014

"S." -- The Triumph of Marginal Characters

by Dale Andrews

SAN ANTONIO — Texas has seen the future of the public library, and it looks a lot like an Apple Store: Rows of glossy iMacs beckon. iPads mounted on a tangerine-colored bar invite readers. And hundreds of other tablets stand ready for checkout to anyone with a borrowing card.

Associated Press, January 3, 2014

Describing San Antonio’s new “bookless” library

There is no debating the fact that the movement, of late, has been away from the hardcover books that were the staple of the golden age of mysteries. Today much reading (mine included) is on tablets, and our personal libraries (and San Antonio's public library) are composed of texts that are stored in the cloud. But whenever something is gained in technology we run the risk of leaving something valuable behind. We will get to that, but first a little backstory.

Back in September I posted an article titled Herewith, the Clues, which discussed the development of “fair play” mysteries, the hallmark of the “golden age” of detective stories. In that article I summarized the birth of the fair play mystery as follows:

Turns out I wrote that article too soon. I hadn't anticipated the recent publication of “S.” , co-authored by movie and television visionary J.J. Abrams and professor, Penn/Hemmingway nominee and three time Jeopardy champion Doug Dorst. To paraphrase Mr. Abrams' re-boot of the Star Trek series, "S." boldy goes where no fair play mystery has gone before. And make no mistake -- "S." is unapologetically a book in every sense of the word.

To date "S." is available only in hardcover, and if you order it from Amazon or Barnes and Noble you are likely to encounter a “temporarily out of stock” notice. (It took about a week for my volume to arrive from Amazon. "S." is currently listed as out of stock without a delivery estimate at Amazon; Barnes and Noble is projecting shipment no earlier than mid-March). When you do finally get your hands on your own copy of this mystery you will begin to understand why, despite strong interest and positive reviews, sales have out-stripped production by the publisher.

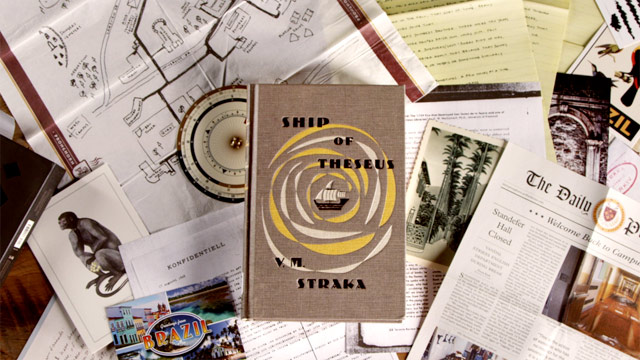

If you order the volume and then wait patiently for delivery, here is what you will eventually hold in your hands -- a handsome cardboard book sleeve containing a hardcover volume, battered and worn, titled Ship of Theseus, purportedly by an author named V.M. Straka. The cardboard box is sealed, and cannot be opened until the paper seal -- the only portion of the book containing the title “S.” -- is broken. Once unsealed, the book presents as a very used library book -- a publication date of 1949, stains on the inside front cover, a “Book for Loan” stamp, a list of check-out stamps on the back inside cover. There is a library index number affixed by sticker on the spine, and the spine itself appears “broken” from frequent opening. When you open the book yourself, it immediately becomes evicent where we, as readers, are headed.

Ship of Theseus is a 453 page novel, complete unto itself. The novel is a good read even standing on its own. But the magic here is that it does not stand on its own. Scribbled throughout all of the pages are notes and annotations by two readers -- Eric, a graduate student who is obsessed with the mysterious Straka, and Jen, a college senior, who has just discovered the author. The premise is that each of them has taken the book from a library shelf, read it, and then returned it to the shelf for the other to re-claim. Eric has initially annotated certain portions in the margin, and Jen responds with her own annotations. Thus begins a dialog that becomes a separate story, sprawling through the pages of Ship of Theseus. In the margins the annotators meet, flirt, and then get down to the task of uncovering the mysteries surrounding Straka and Ship of Theseus, which purportedly was the last of 18 Straka novels (the others are dutifully listed at the front of the book). As if all of this were not enough, as the two annotators discover additional clues or bits of information surrounding the mysterious author, or his equally mysterious translator F. X. Caldeira, they place these snippets of information, or their hand-written summations of what they have uncovered, in the book, at relevant pages, where the reader can extract the clues and follow the evidence at his or her leisure.

And make no mistake -- “leisure” is the right word here. This is a book to be savored, not rushed. In fact, you probably could not rush this book if you wanted to. The reader is called upon to keep track of the underlying Straka novel while, at the same time, following the separate dialog in the margins speculating on the book and the many mysteries surrounding its author. In this respect the book shares some commonality with the underlying theme of Marisha Pessl’s Night Film, discussed at some length in that previous article. The mysterious Stanislas Cordova, who is largely un-seen but occupies the heart of Pessl’s mystery, is eerily similar to the equally-unseen V. M. Straka, who is at the heart of "S.". But back to the point, be prepared to take your time with this book -- you will be rewarded with a near total immersion into the story, a new reading experience that can easily become mesmerizing.

Transforming the concept of the book into a market reality has been a supreme technological challenge, as explained by Abrams in interviews in The New York Times and on CBS. And the problems of the approach continue -- librarians (Rob might like to weigh in here) are perplexed with the challenge of including the book, with all of its loose-leaf clues, on lending shelves, characterizing the task as “a processing nightmare.”

While an ebook version of "S." has been hinted at, it is hard to imagine how this could work. The book, after all, is a throwback -- it is an homage to the published word. In ways it resembles an art book as much as it does a mystery. Could it also be a vanguard? The New York Times had this to say:

Describing San Antonio’s new “bookless” library

There is no debating the fact that the movement, of late, has been away from the hardcover books that were the staple of the golden age of mysteries. Today much reading (mine included) is on tablets, and our personal libraries (and San Antonio's public library) are composed of texts that are stored in the cloud. But whenever something is gained in technology we run the risk of leaving something valuable behind. We will get to that, but first a little backstory.

Back in September I posted an article titled Herewith, the Clues, which discussed the development of “fair play” mysteries, the hallmark of the “golden age” of detective stories. In that article I summarized the birth of the fair play mystery as follows:

An organized approach to writing fair play mysteries dates at least from the 1930s when a number of famous (or soon to be famous) British mystery writers, including Christy, Sayers and Chesterton, to name but three, established the Detection Club with the intention of establishing standards for “fair play” detective stories. Each of the members of the club took the following oath, reportedly still administered today:

Do your promise that your detectives shall well and truly detect the crimes presented to them using those wits which it may please you to bestow upon them and not placing reliance on nor making use of Divine Revelation, Feminine Intuition, Mumbo Jumbo, Jiggery-Pokery, Coincidence, or Act of God?

The members of the Detection Club went on to establish rules of fair play that, by and large, have governed the writing of fair play detective stories ever since. The most important of those rules is that every clue necessary to solve the mystery must be revealed, in advance, to the reader.There have been different experiments over the years focusing on how best to lay out all of those clues before the reader, and my prior article went on to discuss various mysteries that have taken the fair play approach to some intriguing extremes. In that vein, the early “Criminal Dossier” works of Dennis Yates Wheatley and James Gluckstein Links, and the recent best-selling Night Film by Marisha Pessl, were singled out as examples of mysteries that literally served up the clues to the readers -- physical evidence, newspaper articles, written reports, all bound within or otherwise contained in the original volume.

Turns out I wrote that article too soon. I hadn't anticipated the recent publication of “S.” , co-authored by movie and television visionary J.J. Abrams and professor, Penn/Hemmingway nominee and three time Jeopardy champion Doug Dorst. To paraphrase Mr. Abrams' re-boot of the Star Trek series, "S." boldy goes where no fair play mystery has gone before. And make no mistake -- "S." is unapologetically a book in every sense of the word.

To date "S." is available only in hardcover, and if you order it from Amazon or Barnes and Noble you are likely to encounter a “temporarily out of stock” notice. (It took about a week for my volume to arrive from Amazon. "S." is currently listed as out of stock without a delivery estimate at Amazon; Barnes and Noble is projecting shipment no earlier than mid-March). When you do finally get your hands on your own copy of this mystery you will begin to understand why, despite strong interest and positive reviews, sales have out-stripped production by the publisher.

If you order the volume and then wait patiently for delivery, here is what you will eventually hold in your hands -- a handsome cardboard book sleeve containing a hardcover volume, battered and worn, titled Ship of Theseus, purportedly by an author named V.M. Straka. The cardboard box is sealed, and cannot be opened until the paper seal -- the only portion of the book containing the title “S.” -- is broken. Once unsealed, the book presents as a very used library book -- a publication date of 1949, stains on the inside front cover, a “Book for Loan” stamp, a list of check-out stamps on the back inside cover. There is a library index number affixed by sticker on the spine, and the spine itself appears “broken” from frequent opening. When you open the book yourself, it immediately becomes evicent where we, as readers, are headed.

Ship of Theseus is a 453 page novel, complete unto itself. The novel is a good read even standing on its own. But the magic here is that it does not stand on its own. Scribbled throughout all of the pages are notes and annotations by two readers -- Eric, a graduate student who is obsessed with the mysterious Straka, and Jen, a college senior, who has just discovered the author. The premise is that each of them has taken the book from a library shelf, read it, and then returned it to the shelf for the other to re-claim. Eric has initially annotated certain portions in the margin, and Jen responds with her own annotations. Thus begins a dialog that becomes a separate story, sprawling through the pages of Ship of Theseus. In the margins the annotators meet, flirt, and then get down to the task of uncovering the mysteries surrounding Straka and Ship of Theseus, which purportedly was the last of 18 Straka novels (the others are dutifully listed at the front of the book). As if all of this were not enough, as the two annotators discover additional clues or bits of information surrounding the mysterious author, or his equally mysterious translator F. X. Caldeira, they place these snippets of information, or their hand-written summations of what they have uncovered, in the book, at relevant pages, where the reader can extract the clues and follow the evidence at his or her leisure.

And make no mistake -- “leisure” is the right word here. This is a book to be savored, not rushed. In fact, you probably could not rush this book if you wanted to. The reader is called upon to keep track of the underlying Straka novel while, at the same time, following the separate dialog in the margins speculating on the book and the many mysteries surrounding its author. In this respect the book shares some commonality with the underlying theme of Marisha Pessl’s Night Film, discussed at some length in that previous article. The mysterious Stanislas Cordova, who is largely un-seen but occupies the heart of Pessl’s mystery, is eerily similar to the equally-unseen V. M. Straka, who is at the heart of "S.". But back to the point, be prepared to take your time with this book -- you will be rewarded with a near total immersion into the story, a new reading experience that can easily become mesmerizing.

Transforming the concept of the book into a market reality has been a supreme technological challenge, as explained by Abrams in interviews in The New York Times and on CBS. And the problems of the approach continue -- librarians (Rob might like to weigh in here) are perplexed with the challenge of including the book, with all of its loose-leaf clues, on lending shelves, characterizing the task as “a processing nightmare.”

While an ebook version of "S." has been hinted at, it is hard to imagine how this could work. The book, after all, is a throwback -- it is an homage to the published word. In ways it resembles an art book as much as it does a mystery. Could it also be a vanguard? The New York Times had this to say:

Charles Miers, the veteran publisher of the art-book house Rizzoli NY, sees “S.” as part of a larger trend toward such elaborate books, now that digital technology and inexpensive Asian labor have made production newly affordable. “There’s a real interest in the book as an object of permanence, as a direct counterpoint to the digital world, that I haven’t seen before,” he said.The original inspiration for "S." is traceable to the earlier "Mystery Dossiers" of Wheatley and Links, specifically their Who Killed Robert Prentice?, also discussed above and at length in that previous article. In a Los Angeles Times interview Abrams fondly recalled reading that volume: “It had a torn-up photograph in these little wax paper envelopes. As a child, I remember seeing those. That always stayed with me, that idea of getting a book, a packet, that was not just like any other book.” Abrams also acknowledges another catalyst for "S.", a book lending trend that has as well been the subject of some discussion here. According to The New York Times:

Mr. Abrams stumbled upon the idea for “S.” more than a decade ago, when he found a worn Robert Ludlum paperback at Los Angeles International Airport. “Inside, someone had written, ‘To whomever finds this: Please read it, take it, read it and leave it for someone else.’ ” Mr. Abrams said he began thinking about the way his college books had been riddled with marginalia. “What if, instead of putting it back for someone else to read it, the person who received the book saw those notes and felt compelled to continue the conversation?”But perhaps the most remarkable thing about "S." is the way it stubbornly defies modern trends in publishing. This is a book that cannot hope to work well as an e-book. It would never work as a narrated mystery on Audible. It’s hard to imagine that the authors are looking down the road to a paperback edition. What "S." is is an homage to published books -- big, hard cover books, intended to be read and then placed affectionately on a shelf to be retrieved and re-examined in the future. It is about the love affair that can grow between the reader and the volume. There is as much art in the concept as there is in the story -- and this is not meant to denigrate the story, but rather to elevate the concept. Again, according to Abrams:

This is a story about how a book is used as a means of communication and sort of a catalyst for a great investigation that is also a love affair. It is sort of a celebration of ‘the book,’ that physical, analog thing.There may be no room for "S." in that new bookless San Antonio library. That is their loss, but it need not be yours.

Labels:

Dale C. Andrews,

Doug Dorst,

J.J. Abrams,

Theseus,

V.M. Straka

Location:

Chevy Chase, Washington, DC

06 January 2014

A Little Heat and a Lot of Sweet

by Fran Rizer

My younger son Adam has written something I'm very proud of. (Remember my last blog was about prepositions. I'm ending that sentence with "of" on purpose.) This piece of writing could net him a substantial financial prize of $5,000 which is a little more than most of us made from our first authorific efforts.

Adam has written a recipe, not for a cozy, but for a competition. It's one of the eight finalists in the Wild Wing Cafe Battle of the Bones contest. Wild Wings Cafes are located in Florida, Georgia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and Virginia.

You can help him win even if you don't live in one of those states. I'll share how you can assist wherever you are after you take a look at the contest info.

First, let me clarify that the "online" voting mentioned above confused me, and since I once wanted to be an investigative reporter, I called their corporate office and checked. Online voting refers to stating your opinion by email but will not be included in the tally to determine the winner.

Votes which count are only those made in a Wild Wing Cafe. Anyone who orders the ten-piece wings of their choice will be given a sample of the two competitors for that week and a ballot on which they can vote their preference. If your server doesn't offer the ballot, ask for it.

What if you don't live in a town with a Wild Wing Cafe? The other way you can help Adam win this is to post it on your Facebook (preferably every day January 6 -12, 2014). Chances are that some of your friends are in one of the Wild Wings states and will either try Adam's Bulgogi Wings or pass the information on to more and more people through their Facebook listings.

Whether Adam wins or not, I'm proud that his recipe is one of the eight finalists out of over two hundred and fifty entries.

Adam has written a recipe, not for a cozy, but for a competition. It's one of the eight finalists in the Wild Wing Cafe Battle of the Bones contest. Wild Wings Cafes are located in Florida, Georgia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and Virginia.

You can help him win even if you don't live in one of those states. I'll share how you can assist wherever you are after you take a look at the contest info.

Votes which count are only those made in a Wild Wing Cafe. Anyone who orders the ten-piece wings of their choice will be given a sample of the two competitors for that week and a ballot on which they can vote their preference. If your server doesn't offer the ballot, ask for it.

What if you don't live in a town with a Wild Wing Cafe? The other way you can help Adam win this is to post it on your Facebook (preferably every day January 6 -12, 2014). Chances are that some of your friends are in one of the Wild Wings states and will either try Adam's Bulgogi Wings or pass the information on to more and more people through their Facebook listings.

Whether Adam wins or not, I'm proud that his recipe is one of the eight finalists out of over two hundred and fifty entries.

|

| For more info, go to www.wildwingcafe.com |

Until we meet again… eat wings and take care of you!

05 January 2014

What's in a Name?

by Leigh Lundin

by Leigh Lundin

Many common names today have their roots in long ago medieval trades. This is true of non-English names including French, Germanic, and Jewish names. They’re called occupational names and English examples include:

Aptonyms

Many years ago, a columnist for the Orlando Sentinel published what he called ‘aptonyms’, unintentional and usually ironic names that matched (more or less) their occupations, such as Butcher’s Mortuary in Knightstown, Indiana, or Brownie’s Septic Service here in Orlando. In googling today, I see this term has been picked up by others. In fact, there was a Canadian Aptonym Centre. Remember, these few examples are real people and real occupations.

Buffoonery

I pay a lot of attention to the names of my characters, origin, ethnicity, sound, and especially meaning. James Lincoln Warren took note of this in my short story ‘English’. I even developed tools to harvest name information from the web and built a database to help pick names.

At one time, I considered writing a childish farce with comedic names. This sort of thing has to be done adeptly because it’s too easy to overshadow the story with distraction. Ian Fleming barely got away with some of his names like Pussy Galore, which easily could be mistaken for a porn star. And the porn industry is quite a catchall for such monikers like Seymour Butts.

A couple of names work best together, e.g, Willie Maquette, Betty Woant. Others sound like someone might unwisely use them in real life, i.e, Sam's Peck 'n' Paw pet shop.

Names and occupations I’ve considered are:

In a similar vein, Cate Dowse suggested a pair of kneecapping mob enforcers might be called the Patella brothers. I should explain the underlying words for a few of the above names are rubylith (masking film), persiflage (mocking banter), and mispickel (the mineral arsenic is obtained from).

Following are more I didn’t originate, but with my own thoughts on occupations:

What are your names and occupations?

Many common names today have their roots in long ago medieval trades. This is true of non-English names including French, Germanic, and Jewish names. They’re called occupational names and English examples include:

| Bailey Baker Barber Butcher Butler Carter Carver Chandler | Coleman Collier Cooper Dexter Dyer Farmer Fisher Fletcher | Forester Harper Hooper Hunter Mason Miller Palmer Rider | Sawyer Shepard Shoemaker Singer Skyler Smith Spenser Steward | Tanner Taylor Thatcher Tucker Turner Tyler Weaver Wheeler |

Aptonyms

Many years ago, a columnist for the Orlando Sentinel published what he called ‘aptonyms’, unintentional and usually ironic names that matched (more or less) their occupations, such as Butcher’s Mortuary in Knightstown, Indiana, or Brownie’s Septic Service here in Orlando. In googling today, I see this term has been picked up by others. In fact, there was a Canadian Aptonym Centre. Remember, these few examples are real people and real occupations.

| Alex Woodhouse Brian Coates Chad Hacker, Jr Cherish Hart Chris Fotos Dan Langstaff Darin Speed David Bird Debi Humann Dr. Knapp Dr. Robert Scarr Ellen Fair Helen Painter Janet Moo Jardin Wood Jeff Kitchen Jennifer English Jessi Bloom Jim Lawless Jim Playfair Joanie Hemm Joe Puetz | architectural designer paint company manager IT professional American Heart Association owner of portrait studio district court bailiff vintage Mustangs collector ornithologist human resources director anesthesiologist internal medicine physician county superior court judge artist stockyard packer accountant arborist for tree care chef and caterer H.S. English teacher landscaping company owner assistant police chief hockey coach leader of sewing program golf pro | Karl Bench Kestrel Skyhawk Kevin Sill Linda Savage Lorraine Read Marvin Lawless Matt Drumm Michael Laws Mike Blackbird Mike Inks Nita House Norm Mannhalter Penny Coyne Randall Sinn Raymond Strike Robert Marshall Roch Player Sandi Cash Scott Constable Sonia Shears Travis Hots Tyce Tallman | county judge wildlife center educator window shop owner etiquette specialist bookstore owner undersheriff professional percussionist lawyer Audubon Society officer graphic designer real estate agent security supervisor United Way pastor for Lutheran church union leader fire marshal geotechnical engineer accountant policeman hairdresser fire department chief basketball player |

Buffoonery

I pay a lot of attention to the names of my characters, origin, ethnicity, sound, and especially meaning. James Lincoln Warren took note of this in my short story ‘English’. I even developed tools to harvest name information from the web and built a database to help pick names.

At one time, I considered writing a childish farce with comedic names. This sort of thing has to be done adeptly because it’s too easy to overshadow the story with distraction. Ian Fleming barely got away with some of his names like Pussy Galore, which easily could be mistaken for a porn star. And the porn industry is quite a catchall for such monikers like Seymour Butts.

A couple of names work best together, e.g, Willie Maquette, Betty Woant. Others sound like someone might unwisely use them in real life, i.e, Sam's Peck 'n' Paw pet shop.

Names and occupations I’ve considered are:

| Al Dente Ben Dover Billy Reuben Blanche Nutt Claude Butts Jean Poole Jerry Manders Kerry de le Gaj | chef proctologist has a lot of gall flapper girl lion tamer biologist politician concierge | Lotta Goode Miss Pickle Papa Bennett Patty Cache Percy Flage Polly Esther Ruby Lith Willie Evalurn | charity worker spinster poisoner suffers Peyronie's syndrome clerk English vaudeville comedian seamstress graphic arts designer incompetent recidivist |

In a similar vein, Cate Dowse suggested a pair of kneecapping mob enforcers might be called the Patella brothers. I should explain the underlying words for a few of the above names are rubylith (masking film), persiflage (mocking banter), and mispickel (the mineral arsenic is obtained from).

Following are more I didn’t originate, but with my own thoughts on occupations:

| Andover Hand Anita Job Ann Thracks Arthur Itis Bill Jerome Home N. Buddy Holme Faye Slift Frances Lovely Helen Earth Howard I. Kno Ima Dubble Jim Nasium Kareem O’Wheat Kurt Repligh | mountain climber headhunter femme fatale old codger contractor Jehovah’s Witness model travel agent untamed shrew clueless twin fitness trainer Irish/Muslim cook radio host | Leah Tard Lucy Lastick Lynn O’Leum M. T. Wurds Nora Lender Bee Ollie Luya Russell Leeves Scott Linyard Sid Downe Sue Flay Teresa Green Tobias A. Pigg Warren Pease Wayne Dwops | ballerina lingerie model flooring salesgirl salesman not a borrower choir singer landscaper detective and shuddup sous-chef another landscaper marketing guru author weatherman |

What are your names and occupations?

Labels:

aptonyms,

character names,

Leigh Lundin,

silly

Location:

Orlando, FL, USA

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)