16 November 2013

The Death of Posthumous Fame

by Elizabeth Zelvin

I suspect that more and more libraries will refuse donations of papers, especially if the writer isn't unassailably famous. My guess is that thanks to the information explosion in the Internet age (not to mention the fact that more and more documents are electronic rather than actual paper), it will become uncreasingly unlikely for even the most talented and successful writer's reputation to outlive him or her. Margaret Mitchell died in 1949 (64 years), Hemingway in 1961 (52 years), Steinbeck in 1968 (45 years), Truman Capote in 1984 (29 years). What author under 50, if any, do you think will still be a household word, at least among the educated, that long after his or her death?

How much even of these memorable authors’ lasting fame is due not to their books, but to the movies made of their work? I know Gone with the Wind was based on Margaret Mitchell’s book and The Wizard of Oz on L. Frank Baum’s; To Kill A Mockingbird came from Harper Lee’s novel and The Help from Kathryn Stockett’s. How many movie adaptations of novels have you seen in the last twenty years for which you can name the novelist? How many of these will you be able to name twenty years from now? How many do your children know?

The first voluminous volume (760 pages) of Mark Twain’s autobiography came out in 2010. An author whose reputation has proven extremely durable, he deliberately stipulated that it would not be published until a hundred years after his death. so that he would be free to write whatever he wanted without fear of reproach or litigation. Having a sneaky taste for gossip served up cold, I went out and bought the book, making it a birthday present for my husband as a good excuse. Although the prose and some of the anecdotes were delightful, the hundred-years-cold tittle-tattle had gone tepid and congealed.

It’s not that Samuel Clemens did not have an interesting life. According to Biography.com, “When he was 9 years old he saw a local man murder a cattle rancher, and at 10 he watched a slave die after a white overseer struck him with a piece of iron.” He worked as a printer, a steamboat pilot on the Mississippi, and a prospector for gold and silver, the latter endeavor leaving him flat broke. So he became a writer—some things never change! He was a celebrated public speaker and humorist as well as an author for much of his career.

Twain chose to avoid the tedium of a chronological record (“Chapter One: I was born...”) and jumped in wherever his fancy took him. His style, both literate and anecdotal, is so good that I was moved to read some delicious passages out loud. But what even an iconoclast like Twain found shocking a hundred years ago produces no more than a yawn from today’s reader. It’s not a matter of sex or obscenity, with which it’s getting harder and harder to shock the 21st-century reader. It’s not even overt atheism. (You can find some lively debate by googling, “Was Mark Twain an atheist?”) Most of the so-called scandal consisted of his exercising his satiric wit on various popular preachers of the day whose names are otherwise long forgotten.

My prediction: In 2113, no one will remember a single writer who’s alive today, not even JK Rowling, and certainly not James Patterson, who last time I heard had written or cowritten one of every 17 books sold in the USA. Will people still read? I'd like to think so, but Americans will be lucky if reality TV has not driven life to imitate the art of The Hunger Games and if entertainment doesn’t consist of teenagers fighting to the death on the 22nd-century equivalent of public television.

15 November 2013

The Secrets to Writing?

by Dixon Hill

As many of you know, I’ve worked in a cigar store from time to time. What may surprise you, however, is that during my years of employment, I discovered there are large numbers of “secret smokers” in this world.

These folks would duck into the shop only after looking over both shoulders, to be sure none of their friends were watching. Even inside the store, most of them would constantly scan the street outside, watching through the shop windows, keeping their voices low, as if to defeat eavesdroppers.

They acted a lot like prairie dogs who think a hawk might be nearby.

In fact, the first time I was confronted by a secret smoker, in the mid-1990’s, his furtive behavior—combined with the fact that I couldn’t hear what he was asking for, because he wouldn’t speak up— finally led me to say, “If you’re looking for drug paraphernalia, you need to go somewhere else. We’re not that kind of smoke shop, buddy.” The shop owner at the time, Larry Pollicove, came up front, at that moment, saw the guy and quickly sold him a carton of high-end imported cigarettes. (Not a pack, mind you. A carton!)

After the guy left, Larry explained, “That’s (whatever his name was). He’s a good customer, buys a carton a week, but he doesn’t want his wife to know he smokes.”

“How can his wife not know he smokes? He smokes a carton a week; can’t she smell it on him?”

He shook his head. “I don’t think so. She smokes Marlboros.”

“Wait! His wife smokes, but he has to hide the fact that he smokes? Why?”

“Because, he doesn’t know she smokes.” When he saw the look on my face, Larry burst into laughter and slapped me on the back. “Look, she buys her Marlboros from that place on the reservation. I saw her there, and asked why she didn’t buy from me, and she said she was worried her husband would find out she was still smoking. They both agreed to quit, cold turkey, and they both think the other one did. But, actually they both started smoking secretly instead.”

By this time, you’re probably beginning to doubt the veracity of my story. But, it’s absolutely true. Those two people each thought they were married to a non-smoker, but each smoked in secret. And, they smoked a lot.

In fact, there are many reasons people become secret smokers. We used to know when the shift changed at the local fire station, because the fire truck would park out back and all the firefighters would pour in to buy cigars for their opening-shift poker game. When the city switched health insurance companies, though, the firefighters were no longer permitted to smoke. So, they’d take turns coming in for cigars, in civilian clothing, the day before the shift changed, and they started holding “barbeques” in the fenced yard behind the station. Eventually, the health coverage changed again, which we realized when they again began parking the truck out back.

The ranks of secret smokers are also comprised of people who take up teaching jobs, or work in Boys and Girls Clubs, or lead Scout troops. Many of these folks, who smoke, hide their habit out of fear that they’ll lose their position, working with kids, if parents or administrations find out they smoke.

The old Music Teacher at my kids’ elementary school, who’s now retired, used to be a secret smoker. She’d shopped at the store for years, and I’d sold her cigars and cigarettes several times. But, the day I asked how the upcoming school musical production was coming along, her head snapped up and she gave me a “deer in the headlights” look.

The old Music Teacher at my kids’ elementary school, who’s now retired, used to be a secret smoker. She’d shopped at the store for years, and I’d sold her cigars and cigarettes several times. But, the day I asked how the upcoming school musical production was coming along, her head snapped up and she gave me a “deer in the headlights” look.

When I explained that my daughter was in the play, her face paled. “Oh, so you’re one of our parents at (the school).” She was clearly trying to play it cool, but failing miserably. If she worked as a spy, she’d have been shot dead in about ten seconds.

I quickly explained that her secret was safe with me; I wasn’t going to tell anyone she smoked. Her relief was nearly palpable—even from where I stood, across the counter from her. From then on, whenever I sold her tobacco, she’d lift one finger across her lips and remind me, “Mums the word.” I’d nod and pretend to lock my lips shut.

At the shop, she was very friendly, constantly seeking my advice about different cigars, because she was the cigar smoker; her husband was the one who smoked cigarettes. He taught at a different school, but was too afraid to be seen in the shop, so she did the tobacco buying. When I saw her at school, however, she’d act as if she didn’t know me—even pretending not to know my name. I never even knew who her husband was, until he came in after having retired. That was when I discovered he’d been the Assistant Principal at my son’s middle school.

People have other secrets, too, of course. One customer at the cigar store believed he had secretly managed to purchase an entire barrel of whiskey, at a famous distillery, without his wife knowing, while he and she were on vacation in Scotland.

After his purchase matured, he naturally wanted to drink some of it. However, the only way to export it to the U.S. was to bottle it. Evidently, regulations prohibit importation by the barrel, at least for private persons. Consequently, this guy spent incredible amounts of time trying to figure out how to get it bottled in Scotland, then shipped to Arizona—all without his wife finding out. He was also quite parsimonious, so part of his problem was finding the cheapest way to do all this.

The kicker is: She knew all about it. When he went outside to take a call on his cell phone, one day, while the pair were in the shop, she chuckled and announced: “He’s gone outside, because that call’s about his whiskey. He thinks I don’t know he bought a barrel of it while we were in Scotland, ten years ago. Don’t tell him I know, because, whenever he thinks I’m getting suspicious, he buys me gifts to lead me away from the clues. And that skin-flint almost never buys me anything nice!” Everybody roared with laughter, and when the guy came back in, asking what he’d missed, we laughed even harder.

We had a young lady who liked to smoke cigarettes while chatting-up the younger male customers. A good customer once told me he didn’t think she was pretty, which surprised me because everyone else thought she was.

I’ll never forget his words, when I asked why he didn’t think she was pretty. “She’s got ugly feet, man. Big hammer toes! She’s got ugly feet, and she’s an ugly girl.”

Now the cigar store is a place where we give each other a good-natured hard time. So, shortly after that, when a woman walked past the window in sandals, I asked him, “What about her feet? Does she have pretty feet? Or ugly feet?” We were pretty good friends, but he wouldn’t answer me, and I could tell he was getting upset. So, I knocked it off.

Later, I got him alone, and discovered that he was embarrassed because he had a “foot fetish” and didn’t want anyone to know. He hadn’t meant to let the cat out of the bag, earlier. “You—you stupid idiot—you just had to figure it out!” He shook his head. “I should have known.”

I didn’t mention that it hardly took an egghead to figure it out, when he said what he’d said. Instead, I just assured him his secret was safe with me.

The next time he came in with his wife, whom I’d never found even remotely attractive, I noticed that she wore toe rings and a thin silver anklet. Her feet were carefully pedicured, long and thin with glossy polish on her nails. For the first time, I realized why this guy thought his wife was so attractive that he often bragged about her beauty—something no one in the shop could understand.

It was all because of the secret way he looked at her. To him, I think, she was a woman with beautiful feet. Ergo, she was a beautiful woman, which should be glaringly obvious to everyone.

Here was a guy with a secret so important to him, that it deeply influenced his life choices, as well as the way he saw people. Yet, he was afraid to let almost anyone know about that secret.

What must that be like? I wondered. To care so deeply about something, yet be afraid to admit it to anyone. We often hear talk of “closeted” gay people. But, here was a heterosexual person who was just as deep in the proverbial closet as any gay person could possibly get.

He moved away several years ago, and most of the guys who knew him have gone to the four winds since then, which is why I feel safe posting this now. I don’t believe anyone could possibly figure out who it was.

The title of this post, however, is The Secrets to Writing.

What are the secrets to writing? I have no idea, except to say I think you have to figure it out for yourself—because everyone’s secrets are different.

One suggestion I would make, however, is that you might consider giving your characters some secrets of their own.

See you in two weeks!

--Dixon

These folks would duck into the shop only after looking over both shoulders, to be sure none of their friends were watching. Even inside the store, most of them would constantly scan the street outside, watching through the shop windows, keeping their voices low, as if to defeat eavesdroppers.

They acted a lot like prairie dogs who think a hawk might be nearby.

In fact, the first time I was confronted by a secret smoker, in the mid-1990’s, his furtive behavior—combined with the fact that I couldn’t hear what he was asking for, because he wouldn’t speak up— finally led me to say, “If you’re looking for drug paraphernalia, you need to go somewhere else. We’re not that kind of smoke shop, buddy.” The shop owner at the time, Larry Pollicove, came up front, at that moment, saw the guy and quickly sold him a carton of high-end imported cigarettes. (Not a pack, mind you. A carton!)

After the guy left, Larry explained, “That’s (whatever his name was). He’s a good customer, buys a carton a week, but he doesn’t want his wife to know he smokes.”

“How can his wife not know he smokes? He smokes a carton a week; can’t she smell it on him?”

He shook his head. “I don’t think so. She smokes Marlboros.”

“Wait! His wife smokes, but he has to hide the fact that he smokes? Why?”

“Because, he doesn’t know she smokes.” When he saw the look on my face, Larry burst into laughter and slapped me on the back. “Look, she buys her Marlboros from that place on the reservation. I saw her there, and asked why she didn’t buy from me, and she said she was worried her husband would find out she was still smoking. They both agreed to quit, cold turkey, and they both think the other one did. But, actually they both started smoking secretly instead.”

By this time, you’re probably beginning to doubt the veracity of my story. But, it’s absolutely true. Those two people each thought they were married to a non-smoker, but each smoked in secret. And, they smoked a lot.

In fact, there are many reasons people become secret smokers. We used to know when the shift changed at the local fire station, because the fire truck would park out back and all the firefighters would pour in to buy cigars for their opening-shift poker game. When the city switched health insurance companies, though, the firefighters were no longer permitted to smoke. So, they’d take turns coming in for cigars, in civilian clothing, the day before the shift changed, and they started holding “barbeques” in the fenced yard behind the station. Eventually, the health coverage changed again, which we realized when they again began parking the truck out back.

The ranks of secret smokers are also comprised of people who take up teaching jobs, or work in Boys and Girls Clubs, or lead Scout troops. Many of these folks, who smoke, hide their habit out of fear that they’ll lose their position, working with kids, if parents or administrations find out they smoke.

The old Music Teacher at my kids’ elementary school, who’s now retired, used to be a secret smoker. She’d shopped at the store for years, and I’d sold her cigars and cigarettes several times. But, the day I asked how the upcoming school musical production was coming along, her head snapped up and she gave me a “deer in the headlights” look.

The old Music Teacher at my kids’ elementary school, who’s now retired, used to be a secret smoker. She’d shopped at the store for years, and I’d sold her cigars and cigarettes several times. But, the day I asked how the upcoming school musical production was coming along, her head snapped up and she gave me a “deer in the headlights” look.When I explained that my daughter was in the play, her face paled. “Oh, so you’re one of our parents at (the school).” She was clearly trying to play it cool, but failing miserably. If she worked as a spy, she’d have been shot dead in about ten seconds.

I quickly explained that her secret was safe with me; I wasn’t going to tell anyone she smoked. Her relief was nearly palpable—even from where I stood, across the counter from her. From then on, whenever I sold her tobacco, she’d lift one finger across her lips and remind me, “Mums the word.” I’d nod and pretend to lock my lips shut.

At the shop, she was very friendly, constantly seeking my advice about different cigars, because she was the cigar smoker; her husband was the one who smoked cigarettes. He taught at a different school, but was too afraid to be seen in the shop, so she did the tobacco buying. When I saw her at school, however, she’d act as if she didn’t know me—even pretending not to know my name. I never even knew who her husband was, until he came in after having retired. That was when I discovered he’d been the Assistant Principal at my son’s middle school.

People have other secrets, too, of course. One customer at the cigar store believed he had secretly managed to purchase an entire barrel of whiskey, at a famous distillery, without his wife knowing, while he and she were on vacation in Scotland.

After his purchase matured, he naturally wanted to drink some of it. However, the only way to export it to the U.S. was to bottle it. Evidently, regulations prohibit importation by the barrel, at least for private persons. Consequently, this guy spent incredible amounts of time trying to figure out how to get it bottled in Scotland, then shipped to Arizona—all without his wife finding out. He was also quite parsimonious, so part of his problem was finding the cheapest way to do all this.

The kicker is: She knew all about it. When he went outside to take a call on his cell phone, one day, while the pair were in the shop, she chuckled and announced: “He’s gone outside, because that call’s about his whiskey. He thinks I don’t know he bought a barrel of it while we were in Scotland, ten years ago. Don’t tell him I know, because, whenever he thinks I’m getting suspicious, he buys me gifts to lead me away from the clues. And that skin-flint almost never buys me anything nice!” Everybody roared with laughter, and when the guy came back in, asking what he’d missed, we laughed even harder.

We had a young lady who liked to smoke cigarettes while chatting-up the younger male customers. A good customer once told me he didn’t think she was pretty, which surprised me because everyone else thought she was.

I’ll never forget his words, when I asked why he didn’t think she was pretty. “She’s got ugly feet, man. Big hammer toes! She’s got ugly feet, and she’s an ugly girl.”

Now the cigar store is a place where we give each other a good-natured hard time. So, shortly after that, when a woman walked past the window in sandals, I asked him, “What about her feet? Does she have pretty feet? Or ugly feet?” We were pretty good friends, but he wouldn’t answer me, and I could tell he was getting upset. So, I knocked it off.

Later, I got him alone, and discovered that he was embarrassed because he had a “foot fetish” and didn’t want anyone to know. He hadn’t meant to let the cat out of the bag, earlier. “You—you stupid idiot—you just had to figure it out!” He shook his head. “I should have known.”

I didn’t mention that it hardly took an egghead to figure it out, when he said what he’d said. Instead, I just assured him his secret was safe with me.

The next time he came in with his wife, whom I’d never found even remotely attractive, I noticed that she wore toe rings and a thin silver anklet. Her feet were carefully pedicured, long and thin with glossy polish on her nails. For the first time, I realized why this guy thought his wife was so attractive that he often bragged about her beauty—something no one in the shop could understand.

It was all because of the secret way he looked at her. To him, I think, she was a woman with beautiful feet. Ergo, she was a beautiful woman, which should be glaringly obvious to everyone.

Here was a guy with a secret so important to him, that it deeply influenced his life choices, as well as the way he saw people. Yet, he was afraid to let almost anyone know about that secret.

What must that be like? I wondered. To care so deeply about something, yet be afraid to admit it to anyone. We often hear talk of “closeted” gay people. But, here was a heterosexual person who was just as deep in the proverbial closet as any gay person could possibly get.

He moved away several years ago, and most of the guys who knew him have gone to the four winds since then, which is why I feel safe posting this now. I don’t believe anyone could possibly figure out who it was.

The title of this post, however, is The Secrets to Writing.

What are the secrets to writing? I have no idea, except to say I think you have to figure it out for yourself—because everyone’s secrets are different.

One suggestion I would make, however, is that you might consider giving your characters some secrets of their own.

See you in two weeks!

--Dixon

14 November 2013

A NaNoWriMo Reality Check

by Brian Thornton

For those of you who in the writing community who have been living under a rock, November is "National Write a Novel Month." Who declared it such? I have no idea. Someone did, and it stuck.

So every year tens of thousands of people- including several friends of mine sharpen up their metaphorical pencils and go to work, writing furiously, in an attempt to get an entire novel down in the days between November 1st and 31st.

My response to this notion?

Have fun with that.

Maybe it works for some people, but the idea of writing a complete first draft during a month with not one, but two big holidays (sorry folks, I'm a veteran, from a family of veterans, it's a big deal in my house), a full-time day gig, a marriage/mortgage/one year-old to spend time/effort on, holds zero appeal whatever to me. What's more, it held the same level of appeal back when I wasa kidless, single apartment dweller.

The irony of this is if you asked my wife about my work habits, she'd likely tell you I work better under a deadline. She's seen time and again how, when faced with a due date on one of my writing projects, I will pump out content at a rate that she finds truly impressive.

There's a difference, though. One BIG difference.

Put bluntly, my deadlines invariably involve dollar signs.

To be honest, it all comes down to time. I have a finite amount of it. Now moreso than ever. As a result, it's tough to sit down and bang away at something for the hours on end over a month's time required to turn out a draft of a novel. This is not say I can't turn out product, when it comes to fiction, I have a rough time doing it in assembly line fashion. Some folks can do that, and God bless them. For me it's a short-coming. When I'm writing fiction, I have to put a ridiculous amount of thought into it before I even pick up my (metaphorical) pen.

Back before I got married, I entered into a devil's bargain with a nonfiction publisher that had already published several of my books. These guys always wanted the turnaround on their content yesterday, and they didn't want to have to shell out a whole lot for it. I knew this going in.

At the time I was also wrapping up an editing project, where I'd collected and edited some inspiring nonfiction stories. I was working for the same press, with the same editor I'd worked with on my previous books. She knew how I worked, and that she didn't need to micromanage me or hold my hand while I generated content for her. We worked well together.

This new project involved working with a brand-new editor, who had no idea how I worked, and wasn't especially interested in just having the end result of my efforts just miraculously appear on her desk by deadline date. As I said, she was new, and eager to prove herself.

You can probably see where I'm going with this, so I'll just cut to the chase.

The long and the short of it was that after this new editor started up a pissing match with my original editor over my 25%/50%/75% due dates, I wound up completing the first book exactly eight weeks before the TWO new books I had agreed to write for the difficult-to-work-with new editor were due.

These were children's books, with an intended length of 40,000 words apiece. That's 10,000 words per week, folks.

Oh, and by the way, my day gig is teaching. And this eight week period started on September 1.

In other words, eight weeks of every waking moment not working my day gig pretty much consumed in NaNoWriMo on steroids.

Hell.

Somehow I managed to complete the contract. Miraculously both books are still in print to this day, years later. The in-over-her-head editor who caused me so many headaches during this initial back-and-forth was eventually directed by her boss to cc her on all further communication with me about this matter. I won't go into it any further than that, other than to say she is no longer with that publisher, and hasn't been for some time.

So, NaNoWriMo? No thanks. Been there, done that.

And at least I got paid for my trouble!

For those of you who in the writing community who have been living under a rock, November is "National Write a Novel Month." Who declared it such? I have no idea. Someone did, and it stuck.

So every year tens of thousands of people- including several friends of mine sharpen up their metaphorical pencils and go to work, writing furiously, in an attempt to get an entire novel down in the days between November 1st and 31st.

My response to this notion?

Have fun with that.

Maybe it works for some people, but the idea of writing a complete first draft during a month with not one, but two big holidays (sorry folks, I'm a veteran, from a family of veterans, it's a big deal in my house), a full-time day gig, a marriage/mortgage/one year-old to spend time/effort on, holds zero appeal whatever to me. What's more, it held the same level of appeal back when I wasa kidless, single apartment dweller.

The irony of this is if you asked my wife about my work habits, she'd likely tell you I work better under a deadline. She's seen time and again how, when faced with a due date on one of my writing projects, I will pump out content at a rate that she finds truly impressive.

There's a difference, though. One BIG difference.

Put bluntly, my deadlines invariably involve dollar signs.

To be honest, it all comes down to time. I have a finite amount of it. Now moreso than ever. As a result, it's tough to sit down and bang away at something for the hours on end over a month's time required to turn out a draft of a novel. This is not say I can't turn out product, when it comes to fiction, I have a rough time doing it in assembly line fashion. Some folks can do that, and God bless them. For me it's a short-coming. When I'm writing fiction, I have to put a ridiculous amount of thought into it before I even pick up my (metaphorical) pen.

Back before I got married, I entered into a devil's bargain with a nonfiction publisher that had already published several of my books. These guys always wanted the turnaround on their content yesterday, and they didn't want to have to shell out a whole lot for it. I knew this going in.

At the time I was also wrapping up an editing project, where I'd collected and edited some inspiring nonfiction stories. I was working for the same press, with the same editor I'd worked with on my previous books. She knew how I worked, and that she didn't need to micromanage me or hold my hand while I generated content for her. We worked well together.

This new project involved working with a brand-new editor, who had no idea how I worked, and wasn't especially interested in just having the end result of my efforts just miraculously appear on her desk by deadline date. As I said, she was new, and eager to prove herself.

You can probably see where I'm going with this, so I'll just cut to the chase.

The long and the short of it was that after this new editor started up a pissing match with my original editor over my 25%/50%/75% due dates, I wound up completing the first book exactly eight weeks before the TWO new books I had agreed to write for the difficult-to-work-with new editor were due.

These were children's books, with an intended length of 40,000 words apiece. That's 10,000 words per week, folks.

Oh, and by the way, my day gig is teaching. And this eight week period started on September 1.

In other words, eight weeks of every waking moment not working my day gig pretty much consumed in NaNoWriMo on steroids.

Hell.

Somehow I managed to complete the contract. Miraculously both books are still in print to this day, years later. The in-over-her-head editor who caused me so many headaches during this initial back-and-forth was eventually directed by her boss to cc her on all further communication with me about this matter. I won't go into it any further than that, other than to say she is no longer with that publisher, and hasn't been for some time.

So, NaNoWriMo? No thanks. Been there, done that.

And at least I got paid for my trouble!

13 November 2013

Hour of the Gun

by David Edgerley Gates

John Sturges made a fair number of pictures in the course of a thirty-year career as a director. Some of them are pretty good, and some of them are dogs. The best-known are probably BAD DAY AT BLACK ROCK, THE MAGNIFICENT SEVEN, and THE GREAT ESCAPE. He made Westerns, and war stories, and thrillers. He wasn't celebrated for a light touch, and didn't have much luck with the occasional comedy. His full list of credits is here:

http://www.imdb.com/name/nm0836328/?ref_=nv_sr_1

In 1967, he made HOUR OF THE GUN, a sequel to GUNFIGHT AT THE O.K. CORRAL, ten years earlier. He uses a different cast, and the tone is more somber, the biggest change being character. The manic Doc Holliday played by Kirk Douglas is taken over by a saturnine Jason Robards, and the upright Burt Lancaster as Earp is instead imagined by James Garner as far more morally ambiguous. They're still, of course, the heroes, and the Clanton gang the villains, but the movie comes a lot closer to the actual events in Tombstone, in October of 1881.

The real story is about politics, and business rivalries. Wyatt and his brothers were town-tamers, but in return they got a major piece of the action, primarily gambling. They were opportunists, and if not criminal, they were certainly corrupt, and in it for the money. (The best source I've come across is

AND DIE IN THE WEST, University of Oklahoma, 1989, by Paul Mitchell Marks.)

In the movies, though, the Earps are never shown this way. Wyatt himself helped shape his legend, in later years, with Stuart Lake's hagiographic FRONTIER MARSHAL, and John Ford claimed to have gotten the details of the gunfight straight from the horse's mouth. Wyatt was a blowhard and a bully, and a shameless self-promoter, and most of what he told people was snake oil, but you don't spoil a good story for lack of the facts. The end result is that you get Henry Fonda or Burt Lancaster or Hugh O'Brian, to name a few, and almost invariably they're pushed reluctantly to act, moved beyond patience by the evil Walter Brennan or his ilk. The less said about Earp as a cold-blooded killer, the better.

This is where HOUR OF THE GUN gets interesting. The arc of the story, yes, is similar to others, and after Morgan and Virgil are backshot, Morgan dead and Virgil crippled, Wyatt has good reason to go after the guys who did it. But in this telling, Wyatt gives only lip service to making formal arrests. He simply guns the men down.

The best example of this is the death of Andy Warshaw. Earp and his small posse find Warshaw in a back corner of the Clanton spread. Wyatt sits his horse, Warshaw with his back to him, straddling a split-rail fence, smoking.

How much did Clanton pay you? Wyatt asks.

Warshaw, head down, tells him it was fifty dollars.

Fifty dollars. To see a man shot.

I only watched, Warshaw says. I wasn't with the guns.

Wyatt gets off his horse. I'm going to give you the chance to earn another fifty dollars, he says.

I don't want such a chance, Warshaw says.

I'll count to three, Wyatt says. You can draw on two, I'll wait until three.

Warshaw climbs down off the fence and drops his cigarette.

"One."

An empty moment.

"Two."

Warshaw draws on him.

"Three."

Two things about the scene. First, you feel Warshaw's fear. He's facing a known man-killer. In fact, your sympathy is with Andy, because the outcome is foregone. He feels a grievance. He wasn't with the guns. He only watched. The second thing, Wyatt's thrown away the badge. He's become the kind of man he hunts, a man without remorse, beyond the law.

Doc Holliday hands Wyatt a flask. "Here," Doc tells him. "Have a drink. You need it to make this morning stay down, same as I do."

John Sturges made a fair number of pictures in the course of a thirty-year career as a director. Some of them are pretty good, and some of them are dogs. The best-known are probably BAD DAY AT BLACK ROCK, THE MAGNIFICENT SEVEN, and THE GREAT ESCAPE. He made Westerns, and war stories, and thrillers. He wasn't celebrated for a light touch, and didn't have much luck with the occasional comedy. His full list of credits is here:

http://www.imdb.com/name/nm0836328/?ref_=nv_sr_1

In 1967, he made HOUR OF THE GUN, a sequel to GUNFIGHT AT THE O.K. CORRAL, ten years earlier. He uses a different cast, and the tone is more somber, the biggest change being character. The manic Doc Holliday played by Kirk Douglas is taken over by a saturnine Jason Robards, and the upright Burt Lancaster as Earp is instead imagined by James Garner as far more morally ambiguous. They're still, of course, the heroes, and the Clanton gang the villains, but the movie comes a lot closer to the actual events in Tombstone, in October of 1881.

The real story is about politics, and business rivalries. Wyatt and his brothers were town-tamers, but in return they got a major piece of the action, primarily gambling. They were opportunists, and if not criminal, they were certainly corrupt, and in it for the money. (The best source I've come across is

AND DIE IN THE WEST, University of Oklahoma, 1989, by Paul Mitchell Marks.)

In the movies, though, the Earps are never shown this way. Wyatt himself helped shape his legend, in later years, with Stuart Lake's hagiographic FRONTIER MARSHAL, and John Ford claimed to have gotten the details of the gunfight straight from the horse's mouth. Wyatt was a blowhard and a bully, and a shameless self-promoter, and most of what he told people was snake oil, but you don't spoil a good story for lack of the facts. The end result is that you get Henry Fonda or Burt Lancaster or Hugh O'Brian, to name a few, and almost invariably they're pushed reluctantly to act, moved beyond patience by the evil Walter Brennan or his ilk. The less said about Earp as a cold-blooded killer, the better.

This is where HOUR OF THE GUN gets interesting. The arc of the story, yes, is similar to others, and after Morgan and Virgil are backshot, Morgan dead and Virgil crippled, Wyatt has good reason to go after the guys who did it. But in this telling, Wyatt gives only lip service to making formal arrests. He simply guns the men down.

The best example of this is the death of Andy Warshaw. Earp and his small posse find Warshaw in a back corner of the Clanton spread. Wyatt sits his horse, Warshaw with his back to him, straddling a split-rail fence, smoking.

How much did Clanton pay you? Wyatt asks.

Warshaw, head down, tells him it was fifty dollars.

Fifty dollars. To see a man shot.

I only watched, Warshaw says. I wasn't with the guns.

Wyatt gets off his horse. I'm going to give you the chance to earn another fifty dollars, he says.

I don't want such a chance, Warshaw says.

I'll count to three, Wyatt says. You can draw on two, I'll wait until three.

Warshaw climbs down off the fence and drops his cigarette.

"One."

An empty moment.

"Two."

Warshaw draws on him.

"Three."

Doc Holliday hands Wyatt a flask. "Here," Doc tells him. "Have a drink. You need it to make this morning stay down, same as I do."

Labels:

David Edgerley Gates,

John Sturges,

O.K. Corral,

Wyatt Earp

12 November 2013

The Continuous Dream

Creating vivid characters and believable settings is a complex process--or rather, it's at least two processes, since character and setting aren't the same thing. But the these processes have something in common, and that something is the vivid dream.

When I speak to writing students about creating vivid characters, I suggest that they start with a detailed visual picture that they then relate selectively, picking the two or three or half a dozen details that will make a character a unique individual for the reader. The same thing goes for the setting in which their characters move and argue and strike each other with beer bottles.

All of which assumes that the author can see the character and setting and see them as clearly as a recent memory or a particularly vivid dream. In the case of character, you can work from life, using your third-grade teacher or a man you saw on the bus this morning, or you can pick someone out of an ad or an old movie. For settings, you can travel your neighborhood or the globe or pore over the writings of someone who has traveled. Or, yes, you can make up either a character or a setting out of whole cloth. However you start, at some point you have to see that character and that setting. Really see them. Your setting has to be a real place in your mind's eye and your characters real people. (You'll also hear them and smell them and touch them, if you're writing from all your senses, but, for me, seeing comes first.)

When I write, I'm watching a movie in my head, seeing characters in the setting. As they move about, I see what elements to mention, like the heroine's hair being pushed away from her face and falling right back again or the moving shadows from the tree above the patio table at which the murderer sits.

And visualization isn't only important for descriptions. It also helps me avoid "continuity errors," which is a movie term for little mistakes that pop up in a scene when multiple takes are edited together. Like the Gibson cocktail that appears and disappears in front of Cary Grant while he's talking with Eva Marie Saint in the club car in North By Northwest. These things can happen in our writing, too, when we're not visualizing the actions we're describing. A student once gave me a chapter in which a man yanks a derby down to his eyebrows in a show of determination. So far so good, but a line or two later, the same character slaps his forehead in surprise. Try slapping your forehead after you've yanked your derby down. The author had gotten caught up in the dialogue of the scene (which was, incidentally, very good) and stopped visualizing.

Am I claiming that my mental movie is identical in every respect to the one playing inside the reader's head when he or she reads my finished story? No. That would take more detail than even a Gustave Flaubert could cram into a scene. Or else a kind of magic. And yet there is a sort of alchemy at work when the reader completes the circuit and reconstitutes the freeze dried images we put on the page. (The preceding sentence has been submitted for a mixed-metaphor award.) I believe that if my settings are real places for me and my characters real people, my readers will pick up on it. They'll meet me halfway, plugging in the missing details from their own experience or imagination.

And my dream will live on independent of me. Which is something worth seeing.

When I speak to writing students about creating vivid characters, I suggest that they start with a detailed visual picture that they then relate selectively, picking the two or three or half a dozen details that will make a character a unique individual for the reader. The same thing goes for the setting in which their characters move and argue and strike each other with beer bottles.

|

| Quiet Please. Writer Visualizing. |

When I write, I'm watching a movie in my head, seeing characters in the setting. As they move about, I see what elements to mention, like the heroine's hair being pushed away from her face and falling right back again or the moving shadows from the tree above the patio table at which the murderer sits.

|

| Grant, Gibson, and Saint |

Am I claiming that my mental movie is identical in every respect to the one playing inside the reader's head when he or she reads my finished story? No. That would take more detail than even a Gustave Flaubert could cram into a scene. Or else a kind of magic. And yet there is a sort of alchemy at work when the reader completes the circuit and reconstitutes the freeze dried images we put on the page. (The preceding sentence has been submitted for a mixed-metaphor award.) I believe that if my settings are real places for me and my characters real people, my readers will pick up on it. They'll meet me halfway, plugging in the missing details from their own experience or imagination.

And my dream will live on independent of me. Which is something worth seeing.

Labels:

characters,

continuity,

settings,

Terence Faherty,

Visualization

11 November 2013

Comedy, Strange & Weird Thoughts

by Jan Grape

by Jan Grape

The comedy part is the whole plagiarism by one of our country's high profile politicians. Don't know if any of you are a Rand Paul fan but this man obviously does NOT understand plagiarism. If I had written all the words in Wickipedia or the web sites or his books, I would have been upset.

Some news media have suggested that perhaps the author was thrilled that someone in national office would use their words in everything he writes and speaks. Maybe so, and we all know that politicians don't write their own speeches, but still. The funny thing is that the man got mad at everyone who pointed out this plagiarism. Instead of saying, "I've got to check into this, someone in my office needs to go back to school." That probably would have been the end of it. He tries to act as if nothing is his fault. He's ready to fight a duel if dueling was still legal. He talks about references and footnotes and how he can't do that in a speech. What was wrong was saying, "This reminds me of a scene in a movie and I quote?" The more he's vented his rage, the more all his previous work has been checked and more and more plagiarism has been found.

The strange is how CBS's Sixty Minutes was duped by a guy claiming to have been present in Benghazi when our Ambassador was killed. He said he was there watching it all, and how the enemies didn't see him because he hid in the dark. He gave strong details. I haven't read his book but looks like it might be a complete work of fiction. Seems it didn't take much to disprove his story and yet the powers that be at Sixty Minutes didn't do their due diligence. I've heard the reporter and CBS has apologized and I'm waiting for the airing tonight to see if they retract the story on their time on air. I'm also wondering if anyone from that program will be fired.

The weird to me seems that lying has become the normal for politicians and the media. What the heck? We're the ones who tell lies for fun and profit, aren't we? How dare they try to take our jobs away from us. Look, folks it's hard enough to sell our fiction nowadays without everyone and his dog claiming their story is important. And they get national attention for it. I know, I know, politicians and news reporters have been lying for years but suddenly it's become rampant. Well, I for one am sick of these Johnny-come-latelys horning in on our turf. I think we should organize a sit-in demonstration. Any takers? Just spread the news, set the time and place and I'll be there with my sign of protest. I'll bring my goggles in case the fuzz tries to pepper-spray us.

That's all I can write tonight. I have a few things I need to plagiarize for a media outlet or a politician, I can't remember which.

Labels:

60 Minutes,

Jan Grape,

lies,

plagiarism,

politicians

Location:

Cottonwood Shores, TX, USA

10 November 2013

Professional Tips– P. D. James

by Leigh Lundin

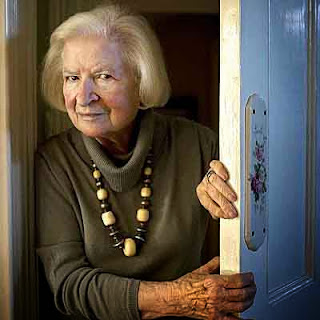

|

| P. D. James © The Times |

As it turns out, the Baroness James has written at least two sets of tips, as noted by one of our readers, which we've gathered in one place. Important: Click the links in the headings for the full articles and explanations.

Writing Tips I, Mystery

- Center your mystery

- Study reality

- Create compelling characters

- Research, research, research

- Follow the 'fair-play rule'

- Read!

- … and write

- Follow a schedule

When working on a story, I daydream a lot, but it's creative daydreaming about the plot, as opposed to dawdling, which the grand dame refers to. There's a story about an actress wannabee who said she wanted to be a famous movie star. "Tell me," said the career counselor. "Do you want to be famous or want to be an actress?" James is saying the same thing: The goal in the front of your mind must be writing the best you can, not fantasizing about fame.

Here again is the Baroness, the inimitable Phyllis Dorothy James, with an update.

Writing Tips II, General

- You must be born to write

- Write about what you know

- Find your own routine

- Be aware that the business is changing

- Read, write, and don't daydream!

- Enjoy your own company

- Choose a good setting

- Never go anywhere without a notebook

- Never talk about a book before it is finished

- Know when to stop

And so I shall.

|

| P. D. James © The Telegraph |

Labels:

Leigh Lundin,

P.D. James,

tips,

writing

Location:

Orlando, FL, USA

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)