It came in the mail.

Writers generally look forward to the mail arriving. Not the bills and junk mail, but the contracts and checks a writer gets for creating work good enough to be put up in print. And sure, we get a little ambivalent, with both hopes and fears, upon receiving those first envelopes from an agent, or editor since they could be a positive or a negative. They could be a glorious validation of our creative genius (also called an acceptance) or the dreaded rejection (what do they know?).

This particular piece of mail I got last month could be called an acceptance of sorts, but not one I was looking for at the time. Can't say I was too surprised to get it though because it's happened twice before in the ten years since we moved here. But why now? After all, we had a trip planned with non-refundable airline tickets, and as everyone knows, airlines recently raised their prices for a customer to change the dates on their tickets.

Guess I could have asked for a postponement, but the letter said it would only take a day or two of my time. Okay, there was a four-day window before flight time, so I took a chance. If circumstances looked bad after I got there, then I could always request a postponement at that time and ask for a later date when my schedule seemed to be more open. In any case, I know they really don't want me. None of them have in the past, even though it has been my desire to participate.

You see, once again my name has come up and I have been summoned for jury duty. My juror number is 1197 and I am supposed to appear in county court at 8:30 AM on a specified day. A lot of instructions are listed in the letter, plus there is a questionnaire form I am supposed to fill out and bring with me. The first part of the form is all background on me. I've known me for a long time, so that part's easy. Next, I check the box for Post Grad and then the NO box for Previous Jury Service.

Now I come to all the little check boxes concerning other background about me, the part which has always gotten me bounced from a jury panel in the past. I check YES for Have You Ever Been Involved In A Court Proceeding Other Than Jury Service. This is quickly followed by checks in the box for The Case Was Civil, also one in the Criminal box, again for I Was A Party To The Case and for I Was A Witness To A Case. Seems my 25 years in law enforcement tends to mean one lawyer or the other in a pending trial has concerns about me sitting on their jury panel. But, according to the rules, no occupation is automatically excused from jury duty. Thus, I am required to go through the motions.

So, the night before, as instructed in the summons, I call the designated telephone number after 5:30 PM. The taped message says numbers 601 through 1,000 must report on the following morning for jury service. Numbers 1,001 through 1,250 are on standby, must be prepared to respond at an hour's notice and are required to call the designated telephone number again at Noon on the following day to see if they are needed then. Okay, looks like No. 1197 has got a second chance with the standbys. I sleep well that night. Comes Noon, the taped message now says the standby group does not need to report, our service obligation as jurors has been fulfilled.

Ah yes, rejected again.

Now, we all know people called for jury duty often make jokes about trying to get out of jury service, some of them serious about their trying or their success. I have even laughed about some of the ploys people used or claimed to have used to get off jury duty. In fact, I found one set of circumstances so bizarre that I used it in a short story ("Independence Day") about one of my Holiday Burglars who ended up on a jury panel for a fellow burglar. In short, it seems a real-life potential female juror raised her hand when the judge asked if there was any reason why any of the potential jurors in front of him should not serve on a jury.

"Yes ma'am," inquired the judge upon seeing her hand.

"I'm not feeling well," was her reply.

"Not feeling well? What is the problem?"

"I think it's the medicine my doctor is giving me for my cocaine addiction."

"Ma'am, you are excused."

Okay, becoming a juror can be an inconvenience. And, okay, people can joke about different ways to get off jury duty. But, I am pretty sure those same people would quickly be screaming about THEIR RIGHTS if the peer jury system was somehow abolished. So, if a little of my time being spent as a juror is one of the requirements for me to live in a free society, then I'm willing to to have the inconvenience of being called. I know that if I were innocent of an accused crime, I would want some jurors who were fair-minded and interested in true justice, not someone who is aggravated about being summoned and is trying to get out of their duty.

Now on the other hand…

21 June 2013

No. 1197

by R.T. Lawton

20 June 2013

How I Got This Way - Literature and Life

by Eve Fisher

Fran's blog on Adolescent Sexist Swill - which was GREAT - got me thinking about the books I read as a child and young adult. Which ones still hold up? Which ones don't? Which ones do I still have on my shelves? Which ones did I get rid of under cover of darkness? I'm going to stick to the mystery/adventure/thriller domain, and so, here's my calls:

The ones that hold up:

Sherlock Holmes - I'm up for a trip to 221B Baker Street just about any time. Just please, don't try to make me like the modern takes on Sherlock. I want him lean, addicted to tobacco and/or cocaine, and totally emotionally detached. (My favorite actor in the role was Jeremy Brett, with Basil Rathbone running a close second.)

Robert Louis Stevenson & Alexandre Dumas - the two greatest adventure story writers ever, imho. One of my first great loves was Alan Breck in "Kidnapped". And while the sequels to "The Three Musketeers" are overwrought to the point of pain ("The Vicomte de Bragelonne" leaps to mind), the original has almost everything anyone could hope for. The rest is in "The Count of Monte Cristo". (Sadly, while I love 1973/74 versions of "The Three Musketeers", I have not yet seen what I consider a decent production of "The Count of Monte Cristo" - they keep wanting to happy up the ending for Mercedes...)

Robert Louis Stevenson & Alexandre Dumas - the two greatest adventure story writers ever, imho. One of my first great loves was Alan Breck in "Kidnapped". And while the sequels to "The Three Musketeers" are overwrought to the point of pain ("The Vicomte de Bragelonne" leaps to mind), the original has almost everything anyone could hope for. The rest is in "The Count of Monte Cristo". (Sadly, while I love 1973/74 versions of "The Three Musketeers", I have not yet seen what I consider a decent production of "The Count of Monte Cristo" - they keep wanting to happy up the ending for Mercedes...)

Nancy Drew - you've got to start somewhere, and she was independent, fun, rescued all her friends, and solved the mysteries. Way to go, Nancy!

Shirley Jackson - I still say the scariest movie ever made was the original "The Haunting" with Julie Harris and Claire Bloom. Check out the books: besides the original "The Haunting of Hill House" allow me to recommend "We Have Always Lived in the Castle". Many of us might recognize an old, old fantasy come strangely to life.

Shirley Jackson - I still say the scariest movie ever made was the original "The Haunting" with Julie Harris and Claire Bloom. Check out the books: besides the original "The Haunting of Hill House" allow me to recommend "We Have Always Lived in the Castle". Many of us might recognize an old, old fantasy come strangely to life.

Edgar Allan Poe - "The Cask of Amontillado" - "for the love of God, Montresor!" "Yes, for the love of God." Wow.

The ones that hold up, with reservations:

H. P. Lovecraft - I gave away my complete set to a young nerd who came back about a week later, strangely gray, and gave them all back to me. He couldn't sleep, couldn't eat, and might have been damaged for life. All I know is Lovecraft scared the crap out of me, I remember some of his stories vividly, a few of them were so brilliant I am still in awe of what he did, and I have no need to ever read them again. (Same thing with "Johnny Got His Gun" by Dalton Trumbo - book and movie - saw it once, read it for some reason after that, had nightmares both times, I am done.)

My adolescent sexist swill (Thanks for the phrase, Fran!):

I will say that at least the Saint had Patricia Holm, who was as much of an adventurer as he was. But then Charteris dropped Patricia. Sigh. And the James Bond novels had some strong women– but most of them, in the end, all went soft and cuddly, even Pussy Galore, which I never believed for one minute… :) But at least the locations were fantastic.

I haven't run across any of Brett Halliday's in a long time, so I don't know how well he holds up, but I have re-read some of all of the others, and... for me, they don't. I can see the line, however, leading from these to Robert Parker's Spenser and Hawk.

My adolescent forerunners:

Agatha Christie - Still the classic, especially when it comes to plotting.

Agatha Christie - Still the classic, especially when it comes to plotting.

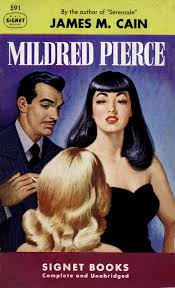

James M. Cain - Mildred Pierce (the book) gets better every year!

Dashiell Hammett - ah. Nick and Nora.

Rex Stout - I am trying to collect the complete works, and I almost have. When it comes to media presentations, I want my Nero Wolfe (like Sherlock Holmes) unblemished by Hollywoodization - overweight, misogynistic, lazy, gourmandizing, and brilliant. (I did like the Timothy Hutton version, although he's not how I've always pictured Archie Goodwin, and Maury Chaykin was not large enough...)

Well enough for now, I'm off to re-read "Death of a Doxy"!

The ones that hold up:

Sherlock Holmes - I'm up for a trip to 221B Baker Street just about any time. Just please, don't try to make me like the modern takes on Sherlock. I want him lean, addicted to tobacco and/or cocaine, and totally emotionally detached. (My favorite actor in the role was Jeremy Brett, with Basil Rathbone running a close second.)

Nancy Drew - you've got to start somewhere, and she was independent, fun, rescued all her friends, and solved the mysteries. Way to go, Nancy!

Shirley Jackson - I still say the scariest movie ever made was the original "The Haunting" with Julie Harris and Claire Bloom. Check out the books: besides the original "The Haunting of Hill House" allow me to recommend "We Have Always Lived in the Castle". Many of us might recognize an old, old fantasy come strangely to life.

Shirley Jackson - I still say the scariest movie ever made was the original "The Haunting" with Julie Harris and Claire Bloom. Check out the books: besides the original "The Haunting of Hill House" allow me to recommend "We Have Always Lived in the Castle". Many of us might recognize an old, old fantasy come strangely to life.Edgar Allan Poe - "The Cask of Amontillado" - "for the love of God, Montresor!" "Yes, for the love of God." Wow.

The ones that hold up, with reservations:

H. P. Lovecraft - I gave away my complete set to a young nerd who came back about a week later, strangely gray, and gave them all back to me. He couldn't sleep, couldn't eat, and might have been damaged for life. All I know is Lovecraft scared the crap out of me, I remember some of his stories vividly, a few of them were so brilliant I am still in awe of what he did, and I have no need to ever read them again. (Same thing with "Johnny Got His Gun" by Dalton Trumbo - book and movie - saw it once, read it for some reason after that, had nightmares both times, I am done.)

My adolescent sexist swill (Thanks for the phrase, Fran!):

The Saint, a/k/a Simon Templar, by Leslie Charteris

The Saint, a/k/a Simon Templar, by Leslie Charteris- Michael Shayne by Brett Halliday

- Mike Hammer by Mickey Spillane

- James Bond by Ian Fleming

I will say that at least the Saint had Patricia Holm, who was as much of an adventurer as he was. But then Charteris dropped Patricia. Sigh. And the James Bond novels had some strong women– but most of them, in the end, all went soft and cuddly, even Pussy Galore, which I never believed for one minute… :) But at least the locations were fantastic.

I haven't run across any of Brett Halliday's in a long time, so I don't know how well he holds up, but I have re-read some of all of the others, and... for me, they don't. I can see the line, however, leading from these to Robert Parker's Spenser and Hawk.

My adolescent forerunners:

James M. Cain - Mildred Pierce (the book) gets better every year!

Dashiell Hammett - ah. Nick and Nora.

Rex Stout - I am trying to collect the complete works, and I almost have. When it comes to media presentations, I want my Nero Wolfe (like Sherlock Holmes) unblemished by Hollywoodization - overweight, misogynistic, lazy, gourmandizing, and brilliant. (I did like the Timothy Hutton version, although he's not how I've always pictured Archie Goodwin, and Maury Chaykin was not large enough...)

Well enough for now, I'm off to re-read "Death of a Doxy"!

19 June 2013

Backtalk

I recently sent the novel

I have been working on to various GFRs (Gullible First Readers) and am

busily contemplating their wisdom. One note from James Lincoln Warren

set me thinking.

He commented on which of the bad guys in my book were punished and which weren't. I replied that I had expected one of them – we will call him Smith – to get away unscathed. As it is, he wound up getting scathed, in spades.

What happened? Well, someone registered such a strong and eloquent protest I had to reconsider. Who was it that insisted Smith pay for his sins?

It was another character in the book. This person – sorry, but I will call him Jones – in effect said: "It's not fair! You've built me up through the novel and never given me anything important to do. I have the personality and the motive to seek revenge. Give me the method and opportunity and get out of my way. Remember Chekhov's gun!"

What my eloquent fictional friend is referring to is a dramatic principle first stated by the great Russian playwright: If a gun is hanging on the wall in the first act, it must be fired in the last. Mr. Jones, was claiming to be that gun, primed and ready.

I have known a lot of writers to talk about their characters "coming alive" and convincing them to change a planned action. I believe I have only experienced it twice.

Besides Jones, the other guilty

party was Cora Neal, writer of women's fiction and beloved wife of

Leopold Longshanks, star of many of my short stories. They have always

had a somewhat testy relationship - well, here is the first sentence of

the first story in the series.

Besides Jones, the other guilty

party was Cora Neal, writer of women's fiction and beloved wife of

Leopold Longshanks, star of many of my short stories. They have always

had a somewhat testy relationship - well, here is the first sentence of

the first story in the series.

"For heaven's sake, Shanks, try to behave yourself today."

They love each other, but Cora does seem to spend a lot of time chewing him out for sins real or imagined. But in one recent story after Shanks had done something outrageous and I expected Cora to complain accordingly, she laughed instead.

I was stunned. It was a completely different side of her personality. And it has effected how I have written about her ever since. (You can see that more clearly in last year's "Shanks Commences" than in this year's "Shanks' Ride").

So let me end with a question for you writers out there: do your characters ever pick fights with you? If so, who wins?

He commented on which of the bad guys in my book were punished and which weren't. I replied that I had expected one of them – we will call him Smith – to get away unscathed. As it is, he wound up getting scathed, in spades.

What happened? Well, someone registered such a strong and eloquent protest I had to reconsider. Who was it that insisted Smith pay for his sins?

It was another character in the book. This person – sorry, but I will call him Jones – in effect said: "It's not fair! You've built me up through the novel and never given me anything important to do. I have the personality and the motive to seek revenge. Give me the method and opportunity and get out of my way. Remember Chekhov's gun!"

What my eloquent fictional friend is referring to is a dramatic principle first stated by the great Russian playwright: If a gun is hanging on the wall in the first act, it must be fired in the last. Mr. Jones, was claiming to be that gun, primed and ready.

I have known a lot of writers to talk about their characters "coming alive" and convincing them to change a planned action. I believe I have only experienced it twice.

Besides Jones, the other guilty

party was Cora Neal, writer of women's fiction and beloved wife of

Leopold Longshanks, star of many of my short stories. They have always

had a somewhat testy relationship - well, here is the first sentence of

the first story in the series.

Besides Jones, the other guilty

party was Cora Neal, writer of women's fiction and beloved wife of

Leopold Longshanks, star of many of my short stories. They have always

had a somewhat testy relationship - well, here is the first sentence of

the first story in the series."For heaven's sake, Shanks, try to behave yourself today."

They love each other, but Cora does seem to spend a lot of time chewing him out for sins real or imagined. But in one recent story after Shanks had done something outrageous and I expected Cora to complain accordingly, she laughed instead.

I was stunned. It was a completely different side of her personality. And it has effected how I have written about her ever since. (You can see that more clearly in last year's "Shanks Commences" than in this year's "Shanks' Ride").

So let me end with a question for you writers out there: do your characters ever pick fights with you? If so, who wins?

Labels:

Anton Chekhov,

characters,

Lopresti,

writing

Location:

Bellingham, WA, USA

18 June 2013

Jesse James and Meramec Caverns: Another Route 66 Story

by Dale Andrews

The guest column by John Edward Fletcher that filled this spot two weeks ago – and particularly an anonymous comment to that article – got me thinking. As noted in John’s column and Leigh’s earlier article exploring the mysteries underlying the death of Laura Foster, the subject was popularized in a 1960s hit song, Tom Dooley, performed by the Kingston Trio. But the trio had another at least near hit when they recorded a new version of the anonymous 1920s song Jesse James. And at least some cloak of mystery surrounds the death of Jesse as well. The story involves Missouri (the State where I grew up), one of the largest and most popular “show caves” in the midwest, a 102 year old man and a flamboyant entrepreneur named Lester B. Dill. Oh yeah -- the story is also sort of a follow-on to Dixon’s musings last Friday on iconic Route 66.

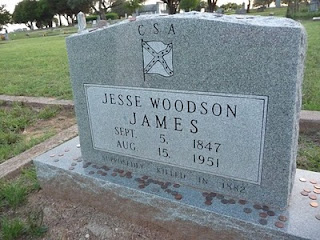

Until the late 1940s, the story of Jesse James’ life was pretty much set in stone. Jesse Woodson James was born in 1847 in Clay County, Missouri. During the Civil War Missouri was a border state. While slaveholding was not prevalent in the State, it was in Clay County, which was known then as “Little Dixie.” The James family owned slaves, and when it came time for lines to be drawn Jesse and his older brother Frank looked south and became active Confederate guerrillas. By all accounts the Civil War was fierce and personal in Missouri -- indeed, in some of the southern counties of the state, particularly Shannon County, it went on at a guerrilla level for many years after Lee’s surrender at Appomattox.

Following a retreat to Tennessee, the James Brothers re-surfaced in St. Joseph Missouri in 1881. There Jesse resumed life under the assumed name of Thomas Howard. On the morning of April 3, 1882 Robert Ford, who had been serving as one of Jesse’s bodyguards, shot and killed Jesse in the living room of his home. Apropos of the words of that Kingston Trio song (which, rather than naming Robert Ford refers to him as “the dirty little coward who shot Mr. Howard”), Jesse’s tombstone contains an epitaph penned by his mother: “In loving memory of my beloved son, murdered by a traitor and coward whose name is not worthy to appear here.” Robert Ford went on to tour with carnivals as “the man who shot Jesse James.” When he himself was shot and killed by Edward Capehart O’Kelley in 1892 O’Kelley toured the same circuit as “the man who shot the man who shot Jesse James.”

A little over 50 years after that shot by Robert Ford, a man named Lester B. Dill enters the story. In 1933 Dill, a local Missouri entrepreneur, who had some experience owning and managing a small “show cave” in Missouri, was looking for a larger cave to acquire and promote. He eventually bought Saltpeter Cave in Stanton Missouri. The cave, as its name suggested, contained rich deposits of saltpeter, a necessary component of gunpowder. During the Civil War the Union had mined saltpeter in the cave, and the operations were eventually dynamited by a Confederate guerrilla force -- which quite likely included Jesse and Frank James.

According to Dalton, Robert Ford had actually shot a man named Charles Bigelow, a Pinkerton Detective who resembled Jesse and purportedly had been committing robberies under Jesse’s name. Dalton’s explanation of how the hoax surrounding his “death” came about was transcribed in a 1949 newspaper account written by Robert C. Ruark for The Evening Independent of St. Petersburg Florida:

Dill, together with his son-in-law Rudy Turilli, who handled publicity for Meramec Caverns, heard about Dalton’s claim and realized the potential of an alliance. He arranged for Dalton to be brought to Meramec Caverns, where Dalton ended up living for the next two years in a cabin at the adjacent motel. While there the elderly Dalton toured the cave, met surviving members of the James Gang, convinced at least some of them in varying degrees that he could be Jesse, and declared that the gang had in fact used the caverns as a hideout between bank robberies.

Second, the evidence from the cave. Dill claims that he discovered strong boxes from the Gads Hill robbery in the cave near loot rock. There are basically three possibilities here -- the boxes could have been left in the cave by someone else, they could have been left there by the James Gang, or the whole story could have been concocted after the fact. Which was it? Well, I leave you to guess. There is at least one problem, however, with Dill’s explanation. There seems to be a tendency of some storytellers to lose track of distances in Missouri. Most recently even Missouri native Gillian Flynn did this in her best seller Gone Girl, where her central character drives from Hannibal Missouri to Ladue Missouri, a distance of 107 miles each way, for lunch. Similarly, the distance from Gads Hill Missouri to Stanton, where Meramec Caverns is located, is 100 miles. And the James Gang lacked automobiles and interstates. Does it make a lot of sense that a strong box would be carried, presumably unopened, 100 miles or more in the 1870s, and then toted underwater into a dark cave only then to be opened? You can be the judge here.

Second, the evidence from the cave. Dill claims that he discovered strong boxes from the Gads Hill robbery in the cave near loot rock. There are basically three possibilities here -- the boxes could have been left in the cave by someone else, they could have been left there by the James Gang, or the whole story could have been concocted after the fact. Which was it? Well, I leave you to guess. There is at least one problem, however, with Dill’s explanation. There seems to be a tendency of some storytellers to lose track of distances in Missouri. Most recently even Missouri native Gillian Flynn did this in her best seller Gone Girl, where her central character drives from Hannibal Missouri to Ladue Missouri, a distance of 107 miles each way, for lunch. Similarly, the distance from Gads Hill Missouri to Stanton, where Meramec Caverns is located, is 100 miles. And the James Gang lacked automobiles and interstates. Does it make a lot of sense that a strong box would be carried, presumably unopened, 100 miles or more in the 1870s, and then toted underwater into a dark cave only then to be opened? You can be the judge here.

Oh yeah, Dill’s billboards advertising that “competing” cave, Onondaga, which he also owned, proclaimed that Onondaga had been discovered by Daniel Boone. Sound familiar? The State of Missouri now owns Onondaga, so the cave's advertisements are now a bit more restrained. The cave’s website addresses Dill's Daniel Boone claim as follows: “there is no valid source hinting this may be true.”

Oh yeah, Dill’s billboards advertising that “competing” cave, Onondaga, which he also owned, proclaimed that Onondaga had been discovered by Daniel Boone. Sound familiar? The State of Missouri now owns Onondaga, so the cave's advertisements are now a bit more restrained. The cave’s website addresses Dill's Daniel Boone claim as follows: “there is no valid source hinting this may be true.”

Members of the James family who were still alive gave no credence to Dalton’s tale and contested his assertions in that Missouri court case. At the conclusion of the trial of that case, during which Dill had unsuccessfully attempted to prove that Frank Dalton was in fact Jesse James, the following statement from Jesse’s daughter-in-law, then still alive but too frail to attend, was read by her lawyer: "Dalton was probably a derelict all his life, and in his waning years he wanted to get a little publicity."

Regardless of who he was or might have been, in that, at least, J. Frank Dalton succeeded. He got his publicity thanks to Lester Dill, Dill's show cave, and a whole lot of signs painted on the roofs of a whole lot of barns along old Route 66.

We’ll get to all of that. But let’s start out with Jesse James.

|

| Jesse and Frank James, 1872 |

After the war, Jesse and Frank, perhaps as early as 1866, began their infamous run of bank and train robberies. By and large the James-Younger gang targeted banks run by Republicans who had stood against the Confederacy during the Civil War, and they didn’t shy away from killing anyone they suspected of Union sentiments. (It’s little wonder that the Kingston Trio’s version of Jesse James added a new line – “Jesse never did a worthwhile thing.”) In any event for years the gang eluded capture with the assistance of Confederate sympathizers in Missouri – indeed, in the 1870s the rivened state legislature only narrowly defeated a bill that would have granted full amnesty to the gang notwithstanding those robberies and murders. But the authorities, outraged by an 1876 robbery of the First National Bank of Northfield, Minnesota and the accompanying bloodshed, eventually mounted a relentless manhunt. Within weeks most of the gang was either killed or captured; only a very few, including Jesse and Frank, were still alive and at large.

|

| Robert Ford (The Dirty Little Coward) |

And so the story of Jesse James ends, right? Well not quite. Still a few carnivals to go.

|

| Lester B. Dill |

Saltpeter, however, was far from Dill’s interest. He renamed the cave Meramec Caverns, after the Meramec River that flows nearby, and began remodelling the huge cavern, which had earlier been used for dance parties by the residents of Stanton, into a show cave, open, for a fee, to the public. Over the years Dill aggressively sought to expand the caverns, and achieved notable success in this regard in 1941, with a discovery that (at least in Dill’s mind) tied the cave to the exploits of the James Gang. The discovery is explained as follows in an article by Phil Dotree at InterestingAmerica.Com.

The connection between Meramec Caverns and Jesse James remained obscure until the summer of 1941, when a rather severe drought hit the area and the water table dropped. Cave guides noted a change in a small pool of water that spilled out of a “dead end” wall. The ever-inquisitive Lester B. Dill decided to go under the wall, through the water, and see what was on the other side. . . . Dill found yet another large network of subterranean passages that fanned out into the limestone . . . .

Acting on his discovery, Dill immediately began constructing an access tunnel that would allow the new section of the caverns to be opened to the public. Dill also claimed that he had found various artifacts in the new caverns, although it is unclear when that claim was first made. But what is clear is that by 1948 the artifacts and Meramec Caverns were linked to Jesse James when a 100 year old man named J. Frank Dalton woke up one morning in his cabin in Oklahoma and declared that he was in fact Jesse.

|

| J. Frank Dalton (Jesse James?) |

Stanton, Mo. - The old man who looks, acts, and talks like Jesse James, and who claims, at 102 years of age, to be Jesse James, says that the man who was killed and buried as Jesse James was a fellow named Charlie Bigelow.

. . . The old man says he had him a string of runnin' horses, and two come down with distemper. 'I fetched 'em to St. Joe to isolate 'em,' he said. 'I had a house there I was not usin' for a spell - not until after some runnin' races at Excelsior Springs. This fellow Charlie Bigelow looked enough like me to be my twin, and he was huntin' a house. I told him and his wife they could use my place for a spell, until after the races, and he moved in.

One day I was out in the barn doctorin' my horses when I heard a gunshot in the house. When I heerd that gun go off I knowed it wasn't no play-party, because we argued with guns in them days. I run into the house and there was Bob Ford, standing over Bigelow with a gun in his hand and blood on the floor. I said to Ford, 'Looks like you killed him, Bob,' and Bob says, 'Looks like I did, Jesse.' Then I says, 'This is my chance, Bob. You tell 'em its me you killed. You tell my mother to say so, and you take care of that Bigelow woman. I'm long gone.'

The old man says he got on one of his horses - a good horse, a four-mile horse - and he lit out.

Thereafter, according to Dalton, he assumed his new identity, eventually settled in Oklahoma, and lived a relatively peaceful 60 years in anonymity.

| Meramec Caverns brochure from the 1950s featuring Frank Dalton and his story |

Thereafter, the artifacts that Dill claimed to have found in the newly opened section of the caverns were displayed at the entrance of the cave, and they included a strong box purportedly linked to a train robbery the James Gang orchestrated at Gads Hill, Missouri, in 1874. Dill also collected various sheriffs’ reports and eyewitness accounts that purportedly linked Jesse James to the caverns, and began an extensive billboard advertising campaign along old Route 66 -- generally painted, for free, on the roofs of barns along the highway -- proclaiming that Meramec Caverns was, in fact, Jesse James hideout.

Although J. Frank Dalton had various scars consistent with wounds that Jesse had reportedly received, and seemed to know many details about Jesse’s exploits, he ultimately was discredited in the eyes of many by a host of inconsistencies in his story. In the late 1960s Dill's son-in-law Rudy Turilli offered a $10,000 reward to anyone who could prove that Dalton was not Jesse. Relatives of Jesse James, including his daughter-in-law, responded with affidavits from family members who had previously positively identified the man shot by Robert Ford as Jesse. A Missouri court agreed with their proof and ordered Turilli (and presumptively Meramec Caverns) to pay the amount as damages for having falsely used Dalton's story, and Jesse James' "good" name, to advertise the caverns. But Dalton's story, along with legends of lost treasure and secret Confederate societies, continues to run rampant on the internet.

So what happened to Dalton? He eventually left his cabin at Meramec Caverns, traveled to Texas and died there on August 15, 1951 three weeks shy of his 104th birthday. His tombstone, notwithstanding that Missouri court ruling, is inscribed with the name "Jesse Woodson James."

|

| J. Frank Dalton's tombstone |

There have been at least two attempts to exhume Dalton’s body for DNA testing, the first of which, in 1995, purportedly showed a 99.5% chance that Dalton was not Jesse James. Similarly, an early exhumation of Jesse’s body – the one shot by Robert Ford – yielded a DNA sample consistent with that of Jesse’s then-living descendants. But the legitimacy of the DNA tests has been debated feverishly, and the conspiracy theorists persist, as any trip to that same friendly internet will reveal.

Was Dalton’s tale, and Dill’s use of that tale to advertise his cave, pure fiction? As noted above, there is still debate on that subject. What can we as mystery writers and readers add to the discourse? Maybe just a few things. Let’s look at some of the evidence discussed above.

|

| Postcard map of Meramec Caverns. Note Loot Rock at center, previously inaccessible except by swimming under a stone barrier wall |

First, the hideout theory. Dalton claimed, to the joy of cave owner Lester B. Dill, that the James Gang regularly used Meramec caverns as a hideout. Indeed, guided tours of the cave to this day proudly display “Loot Rock,” where Dalton claimed the James gang divided up their ill gotten gains. But take a look at the map on the right, and remember the story of how Dill found the portion of the cave in question in 1941 -- the entrance was under water until a season of heavy drought. And the entrance now used by tourists to get to that portion of the cave was carved out of the rock, by Dill, in the 1940s. So how did Jesse’s gang get to Loot Rock in the 1870s? Guides at the cave, at least in the late 1950s when I toured it as a child, explained that the gang swam under the obstructing rock. Some renditions even claimed this was accomplished on horseback. That would mean diving underwater in pitch dark, in a cave that averages sixty degrees, hoping for air (even they could not hope for light) on the other side. Does this make a lot of sense?

Second, the evidence from the cave. Dill claims that he discovered strong boxes from the Gads Hill robbery in the cave near loot rock. There are basically three possibilities here -- the boxes could have been left in the cave by someone else, they could have been left there by the James Gang, or the whole story could have been concocted after the fact. Which was it? Well, I leave you to guess. There is at least one problem, however, with Dill’s explanation. There seems to be a tendency of some storytellers to lose track of distances in Missouri. Most recently even Missouri native Gillian Flynn did this in her best seller Gone Girl, where her central character drives from Hannibal Missouri to Ladue Missouri, a distance of 107 miles each way, for lunch. Similarly, the distance from Gads Hill Missouri to Stanton, where Meramec Caverns is located, is 100 miles. And the James Gang lacked automobiles and interstates. Does it make a lot of sense that a strong box would be carried, presumably unopened, 100 miles or more in the 1870s, and then toted underwater into a dark cave only then to be opened? You can be the judge here.

Second, the evidence from the cave. Dill claims that he discovered strong boxes from the Gads Hill robbery in the cave near loot rock. There are basically three possibilities here -- the boxes could have been left in the cave by someone else, they could have been left there by the James Gang, or the whole story could have been concocted after the fact. Which was it? Well, I leave you to guess. There is at least one problem, however, with Dill’s explanation. There seems to be a tendency of some storytellers to lose track of distances in Missouri. Most recently even Missouri native Gillian Flynn did this in her best seller Gone Girl, where her central character drives from Hannibal Missouri to Ladue Missouri, a distance of 107 miles each way, for lunch. Similarly, the distance from Gads Hill Missouri to Stanton, where Meramec Caverns is located, is 100 miles. And the James Gang lacked automobiles and interstates. Does it make a lot of sense that a strong box would be carried, presumably unopened, 100 miles or more in the 1870s, and then toted underwater into a dark cave only then to be opened? You can be the judge here.

Third, Dill’s own reputation. Lester Dill used to say that he would do “anything” to promote Meramec Caverns. He invented the bumper sticker -- and the only way to avoid having one plastered on your car advertising Meramec Caverns when you visited the cave back in the 1950s was to leave your sun visor down as a signal to the roving parking lot crew. Dill once sent two men dressed as cavemen to the top of the Empire State Building in New York City where they stated they would remain until everyone in the world had visited Meramec Caverns. He engaged in a heated billboard feud with Onondaga Caverns, several miles down the road, as to which was the better cave, without revealing that he in fact also owned Onondaga and that the "feud" was an orchestrated publicity stunt. This is the man who championed the story that Jesse James survived and that he and his gang had used Meramec Caverns as a hideout.

Oh yeah, Dill’s billboards advertising that “competing” cave, Onondaga, which he also owned, proclaimed that Onondaga had been discovered by Daniel Boone. Sound familiar? The State of Missouri now owns Onondaga, so the cave's advertisements are now a bit more restrained. The cave’s website addresses Dill's Daniel Boone claim as follows: “there is no valid source hinting this may be true.”

Oh yeah, Dill’s billboards advertising that “competing” cave, Onondaga, which he also owned, proclaimed that Onondaga had been discovered by Daniel Boone. Sound familiar? The State of Missouri now owns Onondaga, so the cave's advertisements are now a bit more restrained. The cave’s website addresses Dill's Daniel Boone claim as follows: “there is no valid source hinting this may be true.” Members of the James family who were still alive gave no credence to Dalton’s tale and contested his assertions in that Missouri court case. At the conclusion of the trial of that case, during which Dill had unsuccessfully attempted to prove that Frank Dalton was in fact Jesse James, the following statement from Jesse’s daughter-in-law, then still alive but too frail to attend, was read by her lawyer: "Dalton was probably a derelict all his life, and in his waning years he wanted to get a little publicity."

Regardless of who he was or might have been, in that, at least, J. Frank Dalton succeeded. He got his publicity thanks to Lester Dill, Dill's show cave, and a whole lot of signs painted on the roofs of a whole lot of barns along old Route 66.

Labels:

Dale C. Andrews,

Jesse James

Location:

Chevy Chase, Washington, DC

17 June 2013

Adolescent Sexist Swill?

by Fran Rizer

by Fran Rizer

I became a latchkey child at age ten when my mother went to work out of the home for the first time. I immediately thought it would be nice to cook dinner for my family before Mom and Dad got home from work, so I learned to cook; however, I was never fond of washing dishes. My mother washed pots and mixing bowls as she went along, but I tended to pile them up on the counter and wash them right before my parents were due home.

The solution to having to do all that dish and pot washing was that my friends came to my house after school. If I would swipe a novel from one of my father's bookcases and read it aloud to them, they would do the dishes, set the table and damp-mop the kitchen while I read. They'd be finished and gone home in time for me to return the book to Daddy's office before he got home from work.

It would be ridiculous to try to tell how many books we went through including the complete works of O. Henry and Edgar Allan Poe, but I want to tell you about one my favorites. We read Mickey Spillane, and that was hot stuff in those days, but then we discovered some old paperbacks by Richard S. Prather. They were about Shell Scott, the second most commercially successful private eye of the fifties with over forty million sales (second only to Mickey Spillane's Mike Hammer).

At six feet, two inches tall, ex-marine Shell Scott stayed forever thirty years old. His bristly white-blonde buzz cut and almost white eyebrows off set the fact that his nose had been broken and a chunk of his left ear was missing, but my girlfriends and I thought he was hot! He drove a yellow Cadillac convertible, and I wonder if subconsciously that had anything to do with the first car I ever bought in my own name being a yellow Austin Healey convertible.

At six feet, two inches tall, ex-marine Shell Scott stayed forever thirty years old. His bristly white-blonde buzz cut and almost white eyebrows off set the fact that his nose had been broken and a chunk of his left ear was missing, but my girlfriends and I thought he was hot! He drove a yellow Cadillac convertible, and I wonder if subconsciously that had anything to do with the first car I ever bought in my own name being a yellow Austin Healey convertible.

As originally envisioned, Shell Scott was typical of the post-war Spillane character Mike Hammer. They were both private investigators who talked tough and carried guns,but Shell Scott offered more than Mike Hammer.

The usual sex and violence was lightened in Shell Scott's adventures by

what's called "a sort of goofy hedonism." He enjoyed life with a main concern toward looking for the next good time though he did end up serving justice and vengeance like the others. He just had more fun doing it. We adolescents loved it! The wisecracks and double-entendres got wackier and wackier and delighted us kids more and more as Prather increased them and we grew old enough to understand them.

In Way of a Woman (1952) Scott escapes the bad guys by swinging from tree to tree through a movie set--as we say in the South--nekkid as a jay bird in that scene, and boy, we kids pictured and discussed that. Strip for Murder has been described as "a full-out hoot." Scott goes undercover at a nudist camp and ends the book landing a hot air balloon in downtown Los Angeles--nekkid again, of course. The Cock-Eyed Corpse (1964) found Scott disguising himself as a prop on a movie set, which led to the memorable line:

"You won't believe this, but that rock just shot me in the ass."

Prather was also a very successful magazine writer with many stories published in major mystery periodicals of the time. Some of them were excerpts from Shell Scott novels while others were straight-out short stories. He and Stephen Marlowe co-wrote Double in Trouble, but Marlowe's report on writing with Prather didn't make it sound easy. (I'm saving that for my next blog which is about co-writes.)

The Thrilling Detective Web Site described the Shell Scott stories as "smirky, outlandish, innuendo-laden, occasionally alcohol-fueled, off-the-wall tours-de-force that, depending on your point of view, were either a real hoot, or a lot of adolescent, sexist swill and hackwork." Not having read a Shell Scott since adolescence, I wonder if my fascination with him and Prather's stories were because of the genuine appeal of the second best-selling PI writer of the '50s or because I was an adolescent who enjoyed sexist swill and hackwork.

Tell you what I'm going to do--gonna read some of those books again, from a more mature, far more mature, point of view. I'll let you know how much difference the decades make. Meanwhile, if you've read Prather, let us know what you think or tell us about a literary figure you loved in your youth.

Until we meet again, take care of . . . you!

I became a latchkey child at age ten when my mother went to work out of the home for the first time. I immediately thought it would be nice to cook dinner for my family before Mom and Dad got home from work, so I learned to cook; however, I was never fond of washing dishes. My mother washed pots and mixing bowls as she went along, but I tended to pile them up on the counter and wash them right before my parents were due home.

|

| Shell Scott, but he was better looking in my ten-year-old mind. |

It would be ridiculous to try to tell how many books we went through including the complete works of O. Henry and Edgar Allan Poe, but I want to tell you about one my favorites. We read Mickey Spillane, and that was hot stuff in those days, but then we discovered some old paperbacks by Richard S. Prather. They were about Shell Scott, the second most commercially successful private eye of the fifties with over forty million sales (second only to Mickey Spillane's Mike Hammer).

At six feet, two inches tall, ex-marine Shell Scott stayed forever thirty years old. His bristly white-blonde buzz cut and almost white eyebrows off set the fact that his nose had been broken and a chunk of his left ear was missing, but my girlfriends and I thought he was hot! He drove a yellow Cadillac convertible, and I wonder if subconsciously that had anything to do with the first car I ever bought in my own name being a yellow Austin Healey convertible.

At six feet, two inches tall, ex-marine Shell Scott stayed forever thirty years old. His bristly white-blonde buzz cut and almost white eyebrows off set the fact that his nose had been broken and a chunk of his left ear was missing, but my girlfriends and I thought he was hot! He drove a yellow Cadillac convertible, and I wonder if subconsciously that had anything to do with the first car I ever bought in my own name being a yellow Austin Healey convertible.As originally envisioned, Shell Scott was typical of the post-war Spillane character Mike Hammer. They were both private investigators who talked tough and carried guns,but Shell Scott offered more than Mike Hammer.

The usual sex and violence was lightened in Shell Scott's adventures by

what's called "a sort of goofy hedonism." He enjoyed life with a main concern toward looking for the next good time though he did end up serving justice and vengeance like the others. He just had more fun doing it. We adolescents loved it! The wisecracks and double-entendres got wackier and wackier and delighted us kids more and more as Prather increased them and we grew old enough to understand them.

In Way of a Woman (1952) Scott escapes the bad guys by swinging from tree to tree through a movie set--as we say in the South--nekkid as a jay bird in that scene, and boy, we kids pictured and discussed that. Strip for Murder has been described as "a full-out hoot." Scott goes undercover at a nudist camp and ends the book landing a hot air balloon in downtown Los Angeles--nekkid again, of course. The Cock-Eyed Corpse (1964) found Scott disguising himself as a prop on a movie set, which led to the memorable line:

"You won't believe this, but that rock just shot me in the ass."

Prather was also a very successful magazine writer with many stories published in major mystery periodicals of the time. Some of them were excerpts from Shell Scott novels while others were straight-out short stories. He and Stephen Marlowe co-wrote Double in Trouble, but Marlowe's report on writing with Prather didn't make it sound easy. (I'm saving that for my next blog which is about co-writes.)

The Thrilling Detective Web Site described the Shell Scott stories as "smirky, outlandish, innuendo-laden, occasionally alcohol-fueled, off-the-wall tours-de-force that, depending on your point of view, were either a real hoot, or a lot of adolescent, sexist swill and hackwork." Not having read a Shell Scott since adolescence, I wonder if my fascination with him and Prather's stories were because of the genuine appeal of the second best-selling PI writer of the '50s or because I was an adolescent who enjoyed sexist swill and hackwork.

Tell you what I'm going to do--gonna read some of those books again, from a more mature, far more mature, point of view. I'll let you know how much difference the decades make. Meanwhile, if you've read Prather, let us know what you think or tell us about a literary figure you loved in your youth.

Until we meet again, take care of . . . you!

Labels:

Fran Rizer,

Richard Prather,

Shell Scott,

Stephen Marlowe

Location:

Columbia, SC, USA

16 June 2013

The Digital Detective, Wall Street part 1

by Leigh Lundin

High Finance and Low Crimes

I learned a couple of curious things when I worked at IBM’s Wall Street Data Center. One was that my friend, Curtis Gadsen liked mayo sandwiches and fleecy-legged girls. The other was my friend Ray Parchen could be fooled because he was too good at his job as a mainframe computer operator.

Like an old-time

stoker fed the fires of furnaces and steam engines, an IBM operator stuffed the huge machines with programs and data. Very good

operators could act and react instantly without thought, confident in

their experience and skills, mounting discs and responding to messages

as they'd done ten thousand times before, giving them no more thought

than donning their underwear in the morning. The keyword was efficiency.

Unintimidated by hulking computers the public suspected were semi-sentient, Ray worked quickly and accurately, and for that reason, he held down the first shift position. For him, I wrote a silly little psychological program that worked only with the best.

Amidst weighty programs queued for the giants of Wall Street, I slipped in the prank while a dozen employees gathered outside the computer room’s glass wall, waiting for the small program to do its thing: It made discs chatter, tapes whirr, lights blink, and the data center rumble as if Colossus was taking over the world.

We watched Ray bend over the console, reading the first mundane message:

Of course he knew pressure couldn't be detected, but he hadn't engaged his knowledge hidden behind the wall of his expertise. I would discover this common quirk could be exploited, as Simon Templar might say, “by the ungodly.” As noted in the article about kiting, confidence men take advantage of confidence.

Over the next few days, we tried our little joke on other operators and observed this interesting fact: Only the best fell for the stupid little prank. Novice operators stopped, studied the messages, and tried to look them up.

Ray and the other top operators reacted immediately and without thinking. Self-assured of their abilities, they acted instinctively by rote.

Less experienced operators questioned everything, including themselves. We caught more than one systems engineer trying to look up the bogus message number in the reference manuals and they sometimes called for help. That spoiled the little program.

Lesson: Sometimes it’s easiest to fool the most experienced.

There’s a reason I tell this story. It leads to how I became sort of a detective, a digital Dashiel of a Continental Op.

Over the next few weeks, I'll talk about an accidental career as a investigator in a field yet to be invented, that of computer forensics. I reveled in the chase, but my career often hung in the balance under threat of firing, even blackballing. Often the only reward was termination but hey, that happens to all the best private eyes.

Background Noise

An early case exploded with little of my own involvement, or, perhaps because of my lack of involvement. The players: Walston & Co, the nations third largest brokerage house, and Arthur Anderson, the biggest of the Big Eight accounting firms until participation in the Enron scandal brought about its demise. Anderson had dirtied its manicured fingers long before Enron arrived on the scene.

Search the internet for Walston & Co and its Wikipedia entry merely reads "(Walston) was acquired by Ross Perot following pension account fraud and then merged it with Dupont, which had found itself in financial difficulties." Here's the story behind the story.

Despite the Wikipedia gloss-over, the wheels of merger with F.I. DuPont began turning before revelation of Walston’s fraud. Fifteen million in securities had vanished from DuPont’s accounts. The White House grew nervous. Wall Street threw up its collective hands, Oh woe, what to do, what to do?

A Texan rode into town, Ross Perot. He’d bulldozed through the insurance industry (an intriguing inside tale of its own) and encouraged by Felix G. Rohatyn, he made his move on Wall Street. For an initial $30 million, the impossibly old, impossibly young forty-year-old Napoleonic Perot acquired control of one of the Street’s most prestigious houses. (N.B: Regrettably, Time Magazine articles referenced herein require a subscription.)

At the time, that seemed background noise for me, a full-time employee and a full-time student, living paycheck to paycheck and barely sleeping. I couldn't guess how it would alter my career.

Crime on the Street

In the Financial District, denizens simply call Wall Street 'the Street'. Philosophical sorts read a moral into its long, narrow confines, noting it begins at a church and ends at a river: When times get tough, in depression or desperation, one may choose salvation or suicide.

The Street fosters its own culture. On the one hand, a man’s word is his bond– multimillion dollar transactions hinge on verbal promises. On the other hand, huge regulatory holes allow brokerage houses to commit the sleight-of-hand that brought the economy to its knees ten years ago. We can’t say we weren’t forewarned, but in the heady days of deregulation, greed and giddiness carried the day. We never seem to learn industries cannot police themselves.

One of the first observations of the Street is that the market's moody– it reacts, even overreacts to political news of the day. But I stumbled upon other emotions, which included surprisingly little hanky-panky. A few notes from the era:

A precocious if unaware teen, I worked as an IBM shift supervisor in their Wall Street Data Center, Number 11 Broadway. I had the greatest boss, a pretty blonde named Judy Kane. We boys loved her; the girls– not so much.

And I loved software, the machine-level bits and bytes and Boolean stuff. A teenage mad scientist, I found computers a giant puzzle, one I learned to solve and control. It was a battle of wills, me versus machine, immersive therapy for a broken heart (but that's another story). I'd come to know these Daedalus creatures like a mother knows her own children; better even, I'd learned their DNA.

A sales rep, Herb Whiteman, discovered I spent weekends camped in the computer room, teaching myself to program the huge monsters, then catnapping on the couch as the computers blinked and toiled, compiling my routines. Herb asked if I’d be interested in joining a three-man team that would change Wall Street and put video terminals on broker’s desks. Argus Research, the parent company, would double my IBM salary.

The company gave us secretaries and an entire floor of offices, no expense spared. Unfortunately Argus, in the business of prognostication, shortly deduced the economy teetered on the brink of recession and pulled the plug. Not long after Walston & Company hired me as their fancy-pants systems programmer offering tuition reimbursement as part of my hiring package. Me! I was just a kid from nowhere.

Thus began my introduction to low crimes and high finance.

Stay tuned for more next week, Wall Street's big boys and big crimes.

I learned a couple of curious things when I worked at IBM’s Wall Street Data Center. One was that my friend, Curtis Gadsen liked mayo sandwiches and fleecy-legged girls. The other was my friend Ray Parchen could be fooled because he was too good at his job as a mainframe computer operator.

|

| IBM 360 computer room |

Unintimidated by hulking computers the public suspected were semi-sentient, Ray worked quickly and accurately, and for that reason, he held down the first shift position. For him, I wrote a silly little psychological program that worked only with the best.

Amidst weighty programs queued for the giants of Wall Street, I slipped in the prank while a dozen employees gathered outside the computer room’s glass wall, waiting for the small program to do its thing: It made discs chatter, tapes whirr, lights blink, and the data center rumble as if Colossus was taking over the world.

We watched Ray bend over the console, reading the first mundane message:

05483A Press ENTER.Ray pressed the ENTER key. The machine responded with another message:

05483A Press ENTER hard.A few of us watched from outside the computer room as Ray hit ENTER again. The machine came back with:

05483A Press ENTER harder.Ray punched the ENTER key, and a couple of the girls giggled. The computer responded with:

05483A Press ENTER even harder.Ray smacked the key hard, very hard. The machine responded with one last message;

05483I Did it occur to you I can’t tell how hard you press ENTER?Ray looked up with a red-faced grin and spotted us chuckling. Afterwards, he joined us for a drink where we argued why the program fooled some and not others.

Of course he knew pressure couldn't be detected, but he hadn't engaged his knowledge hidden behind the wall of his expertise. I would discover this common quirk could be exploited, as Simon Templar might say, “by the ungodly.” As noted in the article about kiting, confidence men take advantage of confidence.

Over the next few days, we tried our little joke on other operators and observed this interesting fact: Only the best fell for the stupid little prank. Novice operators stopped, studied the messages, and tried to look them up.

Ray and the other top operators reacted immediately and without thinking. Self-assured of their abilities, they acted instinctively by rote.

Less experienced operators questioned everything, including themselves. We caught more than one systems engineer trying to look up the bogus message number in the reference manuals and they sometimes called for help. That spoiled the little program.

Lesson: Sometimes it’s easiest to fool the most experienced.

There’s a reason I tell this story. It leads to how I became sort of a detective, a digital Dashiel of a Continental Op.

Over the next few weeks, I'll talk about an accidental career as a investigator in a field yet to be invented, that of computer forensics. I reveled in the chase, but my career often hung in the balance under threat of firing, even blackballing. Often the only reward was termination but hey, that happens to all the best private eyes.

Background Noise

An early case exploded with little of my own involvement, or, perhaps because of my lack of involvement. The players: Walston & Co, the nations third largest brokerage house, and Arthur Anderson, the biggest of the Big Eight accounting firms until participation in the Enron scandal brought about its demise. Anderson had dirtied its manicured fingers long before Enron arrived on the scene.

|

| Wall Street and Financial District |

Search the internet for Walston & Co and its Wikipedia entry merely reads "(Walston) was acquired by Ross Perot following pension account fraud and then merged it with Dupont, which had found itself in financial difficulties." Here's the story behind the story.

Despite the Wikipedia gloss-over, the wheels of merger with F.I. DuPont began turning before revelation of Walston’s fraud. Fifteen million in securities had vanished from DuPont’s accounts. The White House grew nervous. Wall Street threw up its collective hands, Oh woe, what to do, what to do?

A Texan rode into town, Ross Perot. He’d bulldozed through the insurance industry (an intriguing inside tale of its own) and encouraged by Felix G. Rohatyn, he made his move on Wall Street. For an initial $30 million, the impossibly old, impossibly young forty-year-old Napoleonic Perot acquired control of one of the Street’s most prestigious houses. (N.B: Regrettably, Time Magazine articles referenced herein require a subscription.)

At the time, that seemed background noise for me, a full-time employee and a full-time student, living paycheck to paycheck and barely sleeping. I couldn't guess how it would alter my career.

|

|

| Trinity Church framed by Wall Street |

In the Financial District, denizens simply call Wall Street 'the Street'. Philosophical sorts read a moral into its long, narrow confines, noting it begins at a church and ends at a river: When times get tough, in depression or desperation, one may choose salvation or suicide.

The Street fosters its own culture. On the one hand, a man’s word is his bond– multimillion dollar transactions hinge on verbal promises. On the other hand, huge regulatory holes allow brokerage houses to commit the sleight-of-hand that brought the economy to its knees ten years ago. We can’t say we weren’t forewarned, but in the heady days of deregulation, greed and giddiness carried the day. We never seem to learn industries cannot police themselves.

One of the first observations of the Street is that the market's moody– it reacts, even overreacts to political news of the day. But I stumbled upon other emotions, which included surprisingly little hanky-panky. A few notes from the era:

|

| Miss Francine Gottfried |

- Wall Street can be a mad marketplace when the economy's in a lull. Late one summer, a sweet keypuncher named Francine Gottfried caused a sensation with the mostly male lunch crowd as her 43-23-37 figure bounced down the steps of Chemical Bank & Trust. For a few days, a sort of silly mating season reigned and then, as so often happens, her 15(0) minutes of fame were up.

- Once, as I strolled with my boss down the street, we encountered a beggerman squatting on his flattened cardboard. My boss stopped and chatted with this derelict before moving on. I didn't say anything but he confessed: The homeless man once worked as a broker, what Wall Street called an account executive or AE. When my boss and the man’s wife carried on an affair (and subsequently married), this man– the husband– collapsed in despair. He now lived– literally– on the Street.

- During the 'Hard Hat Riots' (then called the Wall Street Riots), I picked my way through roving construction workers from the rising World Trade Center left by police to run wild, bashing kids protesting the war in Vietnam. On my way to school as police idled, I helped a girl and her boyfriend bloodied by a musclebound thug. It was no contest: the canyon-like Street corralled the teens, leaving them easy pickings by hardhats with pipes and wrenches. That wasn’t one of Wall Street’s prouder moments. Hard-hats went on to attack the city's mayor's office, smashing the face of one of his aides.

A precocious if unaware teen, I worked as an IBM shift supervisor in their Wall Street Data Center, Number 11 Broadway. I had the greatest boss, a pretty blonde named Judy Kane. We boys loved her; the girls– not so much.

And I loved software, the machine-level bits and bytes and Boolean stuff. A teenage mad scientist, I found computers a giant puzzle, one I learned to solve and control. It was a battle of wills, me versus machine, immersive therapy for a broken heart (but that's another story). I'd come to know these Daedalus creatures like a mother knows her own children; better even, I'd learned their DNA.

A sales rep, Herb Whiteman, discovered I spent weekends camped in the computer room, teaching myself to program the huge monsters, then catnapping on the couch as the computers blinked and toiled, compiling my routines. Herb asked if I’d be interested in joining a three-man team that would change Wall Street and put video terminals on broker’s desks. Argus Research, the parent company, would double my IBM salary.

The company gave us secretaries and an entire floor of offices, no expense spared. Unfortunately Argus, in the business of prognostication, shortly deduced the economy teetered on the brink of recession and pulled the plug. Not long after Walston & Company hired me as their fancy-pants systems programmer offering tuition reimbursement as part of my hiring package. Me! I was just a kid from nowhere.

Thus began my introduction to low crimes and high finance.

Stay tuned for more next week, Wall Street's big boys and big crimes.

Labels:

computers,

digital detective,

fraud,

Leigh Lundin,

Wall Street

Location:

Lower Manhattan, New York, NY, USA

15 June 2013

Disinhibition and the New Technology

by Elizabeth Zelvin

When I started doing psychotherapy online a dozen years ago, I learned that psychologists and other technicians had already identified what they called the disinhibition factor in the way people communicated on the Internet. In The Psychology of Cyberspace (2001, revised 2002, 2003, & 2004), psychologist John Suler, who became a collegial buddy of mine when I joined the International Society of Mental Health Online, identified various beliefs that contribute to this disinhibition when people are texting (at that time, not yet a verb in common use) online, including:

Sometimes the lack of inhibition is benign, as when online therapy clients feel safer and reveal themselves more freely than they might in face-to-face therapy in an office, not to mention their daily lives. What makes these particular clients good candidates for online therapy is that they do feel safer writing and not being seen than they do in person and are at their most candid in cyberspace.

At the Sisters in Crime breakfast at Malice Domestic back in May, the woman who sat down next to me looked familiar. She was new to crime writing, and this was her first mystery convention, but we eventually figured out we knew each other from the neighborhood in New York City and had crossed paths in a non-writing area of our lives. Breakfast was over before we’d had time for much conversation. But within three days of getting home and starting to exchange emails, we had discovered several crucial interests in common, shared a lot of personal information, and were both excited about this new friendship.

Sometimes the disinhibition becomes toxic, as in the flame wars—uninhibited hostility and verbal abuse—that can spring up in online group situations such as chats and e-lists. I’ve seen flaming, on and off, in almost all of the mystery e-lists I’ve participated in for the past decade. I’ve even seen it happen in groups of online mental health professionals. On a rational level, they should know better, right? But the disinhibition isn’t rational: it’s a psychological reflex.

When we text asynchronously, as in email, cell phone texting, and on Facebook, we don’t get the constant feedback of face to face communication, small signals that we can interpret as negative reception. Part of what inhibits us in sharing our thoughts is fear of how the listener will receive them. (When we want feedback, as in a therapist’s active listening, there are text-based techniques to provide it. But that’s another story.) To Suler’s take on invisibility, “You can’t see me,” let’s add, “I can’t see you—so I don’t have to worry about what you think of what I’m saying or censor what I say to please you.”

All of the above applies to text. So how do we account for cell phone users’ habit of blatting private matters wherever they are—on the street, on line in the post office, on a crowded bus? That’s an egregious form of disinhibition. Hardened cellphonistas let it all hang out, whether the “it” is marital conflict, finances, or intimate medical details.

I find it mega-irritating when cellphonistas do it. But it’s not a new phenomenon. In New York, where I live, people have always carried on intimate conversations in restaurants and on the subway. I’ve done it myself. One of the city-dweller’s defenses is to create psychological space. Even if the physical distance between me and the strangers at the next table is only an inch or two, as I get absorbed in conversation, I easily forget they’re there. So maybe it doesn’t have as much to do with technology as we think it does.

When I started doing psychotherapy online a dozen years ago, I learned that psychologists and other technicians had already identified what they called the disinhibition factor in the way people communicated on the Internet. In The Psychology of Cyberspace (2001, revised 2002, 2003, & 2004), psychologist John Suler, who became a collegial buddy of mine when I joined the International Society of Mental Health Online, identified various beliefs that contribute to this disinhibition when people are texting (at that time, not yet a verb in common use) online, including:

“You don’t know me.”The truth, even inevitability, of the disinhibition factor quickly became apparent to me when I became an Internet user.

“You can’t see me.”

“See you later.”

“It’s all in my head.”

“It’s just a game.”

“We’re equals.”

Sometimes the lack of inhibition is benign, as when online therapy clients feel safer and reveal themselves more freely than they might in face-to-face therapy in an office, not to mention their daily lives. What makes these particular clients good candidates for online therapy is that they do feel safer writing and not being seen than they do in person and are at their most candid in cyberspace.

At the Sisters in Crime breakfast at Malice Domestic back in May, the woman who sat down next to me looked familiar. She was new to crime writing, and this was her first mystery convention, but we eventually figured out we knew each other from the neighborhood in New York City and had crossed paths in a non-writing area of our lives. Breakfast was over before we’d had time for much conversation. But within three days of getting home and starting to exchange emails, we had discovered several crucial interests in common, shared a lot of personal information, and were both excited about this new friendship.

Sometimes the disinhibition becomes toxic, as in the flame wars—uninhibited hostility and verbal abuse—that can spring up in online group situations such as chats and e-lists. I’ve seen flaming, on and off, in almost all of the mystery e-lists I’ve participated in for the past decade. I’ve even seen it happen in groups of online mental health professionals. On a rational level, they should know better, right? But the disinhibition isn’t rational: it’s a psychological reflex.

When we text asynchronously, as in email, cell phone texting, and on Facebook, we don’t get the constant feedback of face to face communication, small signals that we can interpret as negative reception. Part of what inhibits us in sharing our thoughts is fear of how the listener will receive them. (When we want feedback, as in a therapist’s active listening, there are text-based techniques to provide it. But that’s another story.) To Suler’s take on invisibility, “You can’t see me,” let’s add, “I can’t see you—so I don’t have to worry about what you think of what I’m saying or censor what I say to please you.”

All of the above applies to text. So how do we account for cell phone users’ habit of blatting private matters wherever they are—on the street, on line in the post office, on a crowded bus? That’s an egregious form of disinhibition. Hardened cellphonistas let it all hang out, whether the “it” is marital conflict, finances, or intimate medical details.

I find it mega-irritating when cellphonistas do it. But it’s not a new phenomenon. In New York, where I live, people have always carried on intimate conversations in restaurants and on the subway. I’ve done it myself. One of the city-dweller’s defenses is to create psychological space. Even if the physical distance between me and the strangers at the next table is only an inch or two, as I get absorbed in conversation, I easily forget they’re there. So maybe it doesn’t have as much to do with technology as we think it does.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)