I really enjoyed her speech, it was funny and relatively short—about twenty minutes. And it kept my interest. Much of what I say here is quoted or paraphrased closely from her speech. But I think I misstated her premise in my last piece, saying she talked about What Not to Do. More accurately her speech was about What Makes Books Fail. She started with some anecdotes and wound her way around to that topic.

She opened talking about how happy she was to be in sunny SoCal. Though it hasn’t been as sunny here as it normally is. But I guess coming from Maine anything above 50 is sunny.

She segued into Delia Owens and her phenomenal success with Where the Crawdads Sing. She also talked about The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society, by Mary Ann Shaffer and her niece Annie Barrows which spent many weeks on the NY Times best seller list. Delia Owens was 70 when her debut novel came out. Shaffer, author of Potato Peel was 74 …and died before it came out. The point was it doesn’t matter how old you are or what you look like. You just have to do it. And you don’t even have to be alive to be a debut novelist!

|

| Delia Owens |

|

| Mary Ann Shaffer and her niece Annie Barrows |

“I knew you’d be in here eventually,” he said. “I want to give you this.”

Three guesses as to what he wanted to give her. Okay, time’s up.

He brandished a manuscript—what else? She took it. And to cut to the chase it never got published, at least not traditionally.

Another time she was in a restaurant. A man across from her jumped out of his chair, dashing out of the restaurant. He returned 20 minutes later with a briefcase…holding, well, you know what it was holding.

And then she talked about love, at least Shakespeare in Love. But rather than try to retell what she said, this, from her website, pretty much covers it:

“Young Shakespeare writes ‘Romeo and Juliet’, falls in love, and tries to stay one step ahead of the Queen’s guard. The scene that had me laughing hardest? When a ferryman finds out that Shakespeare’s a writer and asks him, ‘Will you read my manuscript?’”

Do you notice a theme here?

But the real theme of her talk was why some novels get published and others don’t. Why didn’t the butcher’s novel get published? The real theme was:

What Makes Books Fail

Ms. Gerritsen said that there are certain mistakes that are made often that keep one from breaking out or getting a traditional contract. By way of illustration, she talked about Uncle Harry. We all have one, right?

Uncle Harry and Aunt Maude both experienced the same earth shattering event. Harry will talk your ear off, telling you everything that happened, blow by blow, and bore you to death. Maude will tell you the same story and keep you on the edge of your seat. What’s the difference? Maude gives you the high points of the story.

Tess says we need to identify where the emotional high points are. It’s not that Harry isn’t intelligent, but he needs to get a sense of the dramatic. That’s why Maude’s version is better.

She told the story of Michael Palmer’s agent taking him on, even though the agent didn’t like the book, because they thought he had a sense of the dramatic. And when she and Palmer, both doctors, taught a course in writing for other docs who wanted to be novelists, they discovered that most of them, intelligent as they are, and as understanding of all the tech aspects, couldn’t tell a good story because they didn’t have that sense of the dramatic.

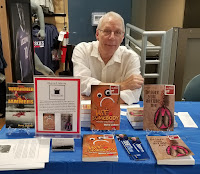

|

| Tess Gerritsen at the 2019 California Crime Writers Conference |

“His book was about a man who comes of age in the turbulent 60s and moves to Maine. ‘And what happens,’ I asked. ‘It’s about self-discovery, about the journey, about coming to grips with life,’ he said. ‘But what happens,’ I said, ‘where’s the conflict? Where’s the struggle?’ And he said, ‘life is a/the struggle.’ And I thought okay, we’re in trouble. So the more I pressed him on the plot and the characters, the more I heard about actualization and personal journeys and maximizing relationships. And in a fit of frustration, I finally just said, ‘you’re thinking too hard. You should be feeling the story,’ and that’s what I’ve come to conclude, is that what makes most stories fail is that people are thinking too hard and they’re not feeling their way. In a nutshell, writers really shouldn’t be cerebral, shouldn’t be logical. We should be thinking about the dramatic points in our lives, the emotional centers in our lives.”

And one more example: Another man wrote a scene about a family preparing a BBQ. He wrote it in great detail, the cooking, the salads, every little thing. And then his grown child telling the dad that “we’re going to have a baby.” That’s great, the dying dad says, congratulations, and they go in and have dinner. But the author didn’t let the characters chew on that. Didn’t play off the emotional core of the scene, the dying man becoming a grandfather. It was just glossed over.

Tess said she remembers the day she was told she was going to have her first grandchild. Her son, who has a flair for the dramatic, showed her a sonogram on the rim of the Grand Canyon. She and her husband started sobbing. She doesn’t remember the hike or how she got to the rim. She only remembers about the baby, now her five year old granddaughter. So, she told the man writing about the BBQ he shouldn’t pass over the emotional center so quickly and spend so much time on the steaks being medium rare. She couldn’t remember the trip to the Grand Canyon. Every bit about the salad or how the steaks were cooked wasn’t what was important.

How a book fails, she said, is that we fail to remember that we’re human beings. It’s all about emotions, not about telling. And a large part of our skill is choosing the scenes—which scene/s are you going to point out? What are the details that matter to you? And even though we sometimes have to deal with technical aspects of what’s happening, we still need to find the emotional things there.

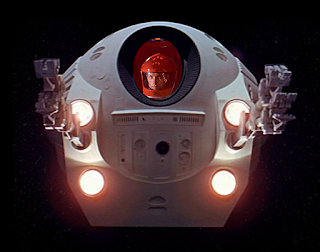

She used her book Gravity as an example. She had to explain the technical aspects of a spacewalk. But she didn’t have the heart of her story until she read Into Thin Air, where one of the climbers, who knew he was doomed to die on the mountain, called his wife to say goodbye. That brought Tess to tears and gave her the spark for the emotional center for Gravity. What is your last goodbye going to be like? Make your story interesting by bringing in your emotions.

So, even when you do need to tell, as we sometimes do, you need to find the emotions of the scene. Show something from the point of view of what you and your characters are feeling.

The bottom line:

What she’s learned is: trust your heart. That’s where your story needs to be. Don’t tell, but show. Choose the scenes that have the highest amount of gravitas and angst, and maybe we’ll all be Delia Owens someday.

~.~.~

And now for the usual BSP:

My story Past is Prologue is out in the new July/August issue of Alfred Hitchcock Mystery Magazine. Available now at bookstores and newstands as well as online at: https://www.alfredhitchcockmysterymagazine.com/. Also in this issue are fellow SleuthSayers Janice Law, R.T. Lawton and B.K. Stevens. Hope you'll check it out.

Please join me on Facebook: www.facebook.com/paul.d.marks and check out my website www.PaulDMarks.com

Click here to: Subscribe to my Newsletter