A few weeks ago I reached a milestone, of sorts: I sold my 100th story to

Woman's World magazine. Allow me to mention, here, how grateful I am to both their editors and their readers, for allowing me to keep spinning these tales. I hope they'll want to buy a hundred more.

I'd also like to thank Dan Persinger, Jacqueline Seewald, Teresa Garver, Kevin Tipple, and others whose recent mentions of my

WW stories on Facebook and elsewhere prompted me to write this piece.

Woman's World is a market that is often overlooked by mystery writers, but if you enjoy--and have a knack for--creating very short stories, it's probably a market you should try.

Background info

As some of you know,

Woman's World publishes one mystery story and one romance story in every issue. The magazine has a circulation of around two million readers/subscribers, they operate under the Bauer Media Group, they're based in New Jersey, and they've been around since 1981. I'm told they receive about 4,000 short-story submissions a month.

When I started submitting stories to

WW almost twenty years ago, their mysteries were 1000 words in length and paid $500 each and their romance stories were 1500 words and paid $1000 each. Now, mysteries are 700 words max and pay $500 and romances are 800 words max and pay $800.

In January 2016 Patricia Riddle Gaddis replaced Johnene Granger as Fiction Editor of the magazine. I can't say enough about these two ladies: both of them are smart, professional, and talented, and both have been very good to me.

Although WW's mystery stories are often referred to as mini-mysteries, the correct term is now "solve-it-yourself" mysteries. More about that later.

Observations

Almost all the stories I've sold to

WW have been mysteries--but two were romances, published years ago. I think those 1500-worders were much easier to write than the current 800-worders, and I have a lot of respect for those who can consistently write those short romance stories. It didn't take me long to figure out which genre was easier for me.

My first

WW stories appeared in 1999, in their April 20, July 20, and July 27 issues. Afterward, I sold them one story in 2000, one in 2001, three in 2002, one in 2003, three in 2004, six in 2005, four in 2006, three in 2007, four in 2008, two in 2009, four in 2010, six in 2011, seven in 2012, ten in 2013, six in 2014, eight in 2015, ten in 2016, thirteen in 2017, and (so far) five in 2018. More than you wanted or needed to know, right?

In 2001 I began featuring two recurring characters in my

WW stories, which has worked out well. For one thing, since readers are now relatively familiar with the two protagonists and their quirks (my characters have a lot of quirks), I don't have to waste much time "introducing" them in each story. That allows me more words to devote to the plot.

Not that it matters, but 62 of my 100 stories sold to

WW involved either a robbery or a burglary. Only 21 involved murders. The rest were a mix of kidnappings, arson, fraud, jailbreaks, assault, blackmail, embezzlement, forgery, etc. I think there's a reason for that, although I doubt I was aware of it at the time:

WW has always liked lighthearted tales, and non-lethal crimes like theft and trickery and property damage are a bit less traumatic than homicides.

Still on the subject of statistics, 92 of my 100 sales have been series stories, the rest of them standalones. And only 19 were whodunits. Most were howdunits. I've often heard that to write mysteries for WW you should have three suspects, and the guilty person must be one of those three. That's bad advice. You can do that if you want, but you don't

have to. The main goal should merely be to put together a crime puzzle of some kind,

not necessarily a whodunit, and make it entertaining.

In 2004 the top brass at

WW decided to move to "interactive" mysteries rather than mysteries with traditional storylines. Hence the new name "solve-it-yourself" mysteries, where a question is introduced in the story and the answer is provided in a solution box at the end of the piece. I confess that I lobbied against this idea--I liked the freedom and variety of the traditional storytelling format--but they'd already made up their minds. And, as I think I've said in the past, when the train you want to ride comes blasting through the station, you can either (1) climb onto it, (2) get squashed, or (3) get left behind. I hopped aboard.

As part of

WW's transition from regular mysteries to interactive mysteries, I was invited by the fiction editor to write several experimental stories that would help to ease readers into the new format. The first of these ("Customer Service," Dec. 14, 2004, issue) included--get this--six clues that were not only

highlighted in the text but were designated as "CLUES." (Did I mention that this was a "trial-and-error" transition?) Anyhow, i happily wrote the story, but I told them I didn't like the "announcement of clues" approach, and

WW agreed. Afterward, the solve-it-yourself mystery became just a story and a solution box, and it remains so today.

Here's something crazy: On two different occasions, my stories were published under another writer's byline. (How did this happen? Who knows.) Both times editor Johnene Granger phoned me afterward to apologize, and I think she was relieved to find that the mistake didn't bother me at all. The checks came on time, the bank cashed them with no problem, and my ego survived the ordeal.

At one point, after WW had published eight of my standalone stories and 23 installments of my "series," I decided to try sending them a story with two different main characters. The editor bought and published that story ("The Quilt Caper," May 17, 2010, issue), but then sent me a note saying she preferred I go back to my tried-and-true cast. Since Mama didn't raise no fools, I saluted and obeyed. My other two crimesolving characters, Fran and Lucy Valentine, did survive, though: they've now appeared in 56 stories, most of them in

Sherlock Holmes Mystery Magazine,

Flash Bang Mysteries,

Mysterical-E,

Kings River Life, and several anthologies--but they've never appeared again in

WW.

One of the best things about

Woman's World is its professionalism. They've

always gotten the contracts to me on time and paid me on time. Always. And they've been easy to work with, on proposed changes. They've also twice paid me "kill fees" (twenty percent of the full rate) when they found they were unable to publish stories that they'd previously accepted. (This happened in 2004, during the trial-and-error transition from one mystery format to the other.)

Another good thing is that the editor sometimes

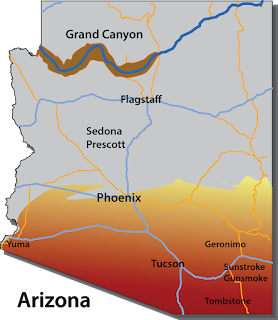

asks me to write a story--especially if there's a holiday coming up and they don't have a story in hand that they want to run. Several years ago, for example, the editor contacted me and said she needed a Fourth of July mystery. "And I need it by tomorrow," she added. I came up with an idea that night, wrote the story, sent it to her the following morning, they published it, and everyone was happy. That doesn't happen often, but when the editor asks me for something, I try really hard to deliver it. (I feel the same way about invitations to anthologies: if someone thinks highly enough of me to invite me to contribute a story, I'm not going to say no.)

A final observation, more about me than about

WW: I don't write only short-short stories. Most of my stories these days seem to run between 3000 and 8000 words--several of those are upcoming in

AHMM,

EQMM,

Strand Magazine,

Black Cat Mystery Magazine,

The Saturday Evening Post, etc.--but there's something about the little mini-mysteries that's always been fun for me. Part of it's probably because I actually enjoy the re-writing and self-editing phase, the whittling away of all the extra and unneeded stuff that most of us plug into our stories. As you flash-fiction writers know, stories of less than 1000 words require a lot of this.

A word about editing

I must tell you,

WW does like to edit my manuscripts. Usually just a word or two, but sometimes more. Example: In my story "Fun and Games," which was published a few weeks ago in the June 11 issue, my Sheriff Jones character and his amateur-sleuth partner Angela Potts have arrived at the local college library, where Professor Harriet Pinskey informs them that a golden statuette of a regal woman in Roman attire--presented to Pinskey's organization by a European billionaire--has been stolen from a display case. The following is some dialogue between the sheriff, Angela, and the professor:

"What organization?" the sheriff asked.

"An all-female academic society," Pinskey said. "MOLTH. It means: Move Over--Ladies Thinking Here."

The sheriff grinned. "Why not 'Women'? That'd be appropriate: MOWTH."

"You better shut yours," Angela said. "You're outnumbered."

Yes, I know it's silly, and certainly not necessary to the plot, but I love this kind of idiotic humor. Alas, the editors did not: that exchange didn't appear in the final, printed version.

On one occasion (in my story "The Train to Graceland," June 30, 2014, issue) my robbery victim was a young Chinese lady. For some reason, the Powers That Be at

WW didn't like that, and I was asked to change the woman's nationality. I made her British instead, and all was well. I'm still trying to figure that one out.

Sometimes titles get changed, as well. Out of the 100 stories I've done for

WW, 49 of my title choices were overruled. A few of their new titles, I must admit, wound up sounding better than my originals--but some didn't. I truly loved one of my titles, to a story involving the robbery and kidnapping of a guy named Ron. My suggested title was "Take the Money and Ron," which in all modesty I thought was pretty clever; their title, the one that made it in to the magazine, was "Candid Camera." Big sigh.

Tips

Here are a few things I would suggest a writer do, if he/she wants to write mystery stories for

Woman's World:

- Include a lot of dialogue.

- Don't use strong language or excessive violence.

- Avoid politics, religion, social issues, or anything else that might be controversial.

- Don't put pets in jeopardy. Go ahead and whack Professor Plum on the head with the candlestick in the parlor if you like, but do NOT dognap his poodle. Around that corner lies immediate rejection.

- Inject some humor. Sometimes it gets edited out, sometimes it doesn't--and it usually helps.

- Be fair with the clues.

- Keep the solutions short.

- Lean toward cozy. About six months ago

WW decided to focus more on lighter subject matter and less on murder mysteries. As a result, all the stories I've sold them so far this year involved domestic, non-violent crimes. Just saying.

Questions

Questions

Have you ever tried sending a story to

Woman's World? Have you been published there? (Several of my fellow

SleuthSayers have been.) If so, what were some of your experiences? Do you find these very short mysteries easier to write than the typical mystery tales--or harder?

If you've never tried it, give it a go. As I mentioned, most of my stories are longer rather than shorter--I honestly enjoy writing those, and we all know a longer story offers the writer a lot of working-room for the plot. But there's something I also like about trying to tell an entire story in a matter of only two or three pages.

You might find you like it too.

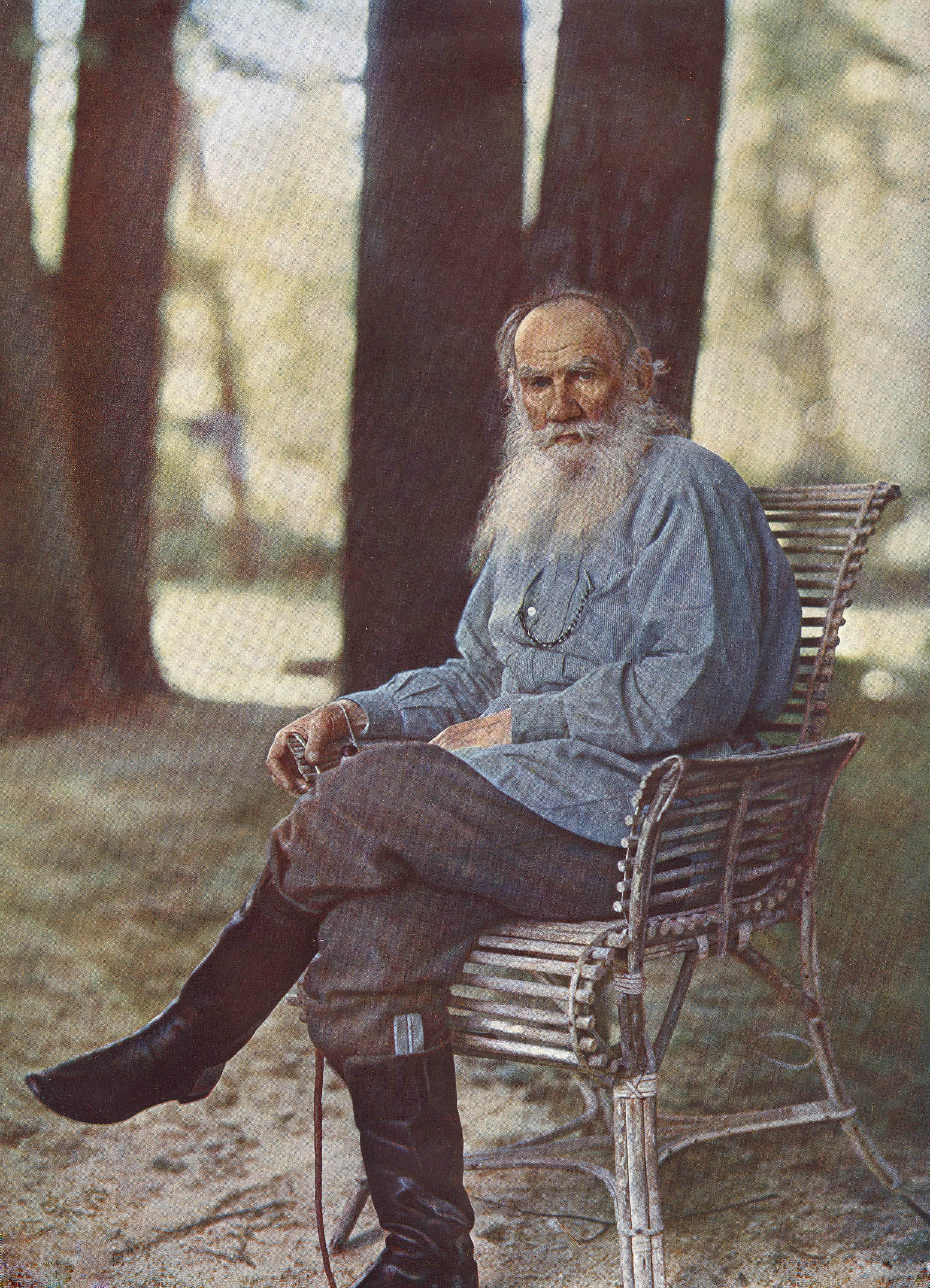

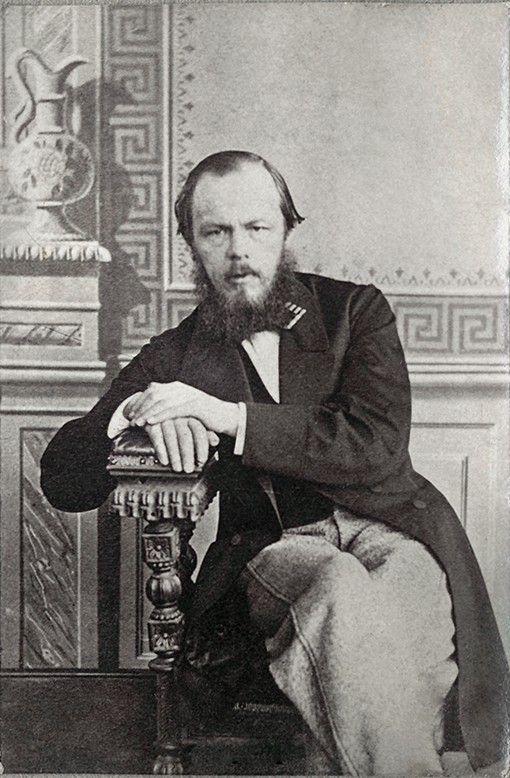

These two writers had one thing in common, besides their love of the short form and their talent with mystery/crime stories: both had a minimalist style that was long on dialogue and humor and short on exposition and description, and almost always included surprise endings. In their stories, things started out fast and never slowed down. I love that.

These two writers had one thing in common, besides their love of the short form and their talent with mystery/crime stories: both had a minimalist style that was long on dialogue and humor and short on exposition and description, and almost always included surprise endings. In their stories, things started out fast and never slowed down. I love that.