The spaciousness of it astounds me; this is the kind of country you dream of running away to when you are very young and innocently hungry, before you learn that all land is owned by somebody, that you can get arrested for swinging through trees in a loincloth, and that you were born either too late or too poor for everything you want to do.

Peter S. Beagle

I See by my Outfit

On July 7, 1919 a young army captain named Dwight David Eisenhower joined 294 other members of the army and departed from Washington D.C. in the military's first automobile caravan across the country. Due to poor roads and highways, the caravan averaged five miles per hour and took 62 days to reach Union Square in San Francisco.

Interstate Highways:

The Largest Public Works Project

in History

U.S. Department of Transportation, Government Printing Office

|

| Time to run away from home! |

Each year our drive takes us along Highway 81 through the Shenandoah Valley and then Roanoke. Eventually we veer off on I-75 through Knoxville, and then on to Chattanooga, where we will spend the night. The next day we will begin heading south again, past Lookout Mountain, site of the Civil War battle that bears its name. Fleetingly we will skirt Georgia before our southerly run continues down the State of Alabama, through Birmingham, and then just east of Monroeville, where Harper Lee still resides. Eventually we will cross the Intracoastal Waterway where we will likely stop for lunch at Lulu's (owned and run by Jimmy Buffett's sister). And then we are there. All of this, except the last few miles, is on interstate highways that plot a rhumb line to the Gulf.

Each year our drive takes us along Highway 81 through the Shenandoah Valley and then Roanoke. Eventually we veer off on I-75 through Knoxville, and then on to Chattanooga, where we will spend the night. The next day we will begin heading south again, past Lookout Mountain, site of the Civil War battle that bears its name. Fleetingly we will skirt Georgia before our southerly run continues down the State of Alabama, through Birmingham, and then just east of Monroeville, where Harper Lee still resides. Eventually we will cross the Intracoastal Waterway where we will likely stop for lunch at Lulu's (owned and run by Jimmy Buffett's sister). And then we are there. All of this, except the last few miles, is on interstate highways that plot a rhumb line to the Gulf.

When you feel like getting away, well . . . there is nothing like a road trip. Driving the highways speaks to me, as it does to many, as resonantly in my 60’s as it did in the 60’s. The road beckons many of us, and that is reflected throughout our lives, and often our literature.

As a college student sometime back in the mid-1960’s I remember wandering into the West End Library in Washington, D.C. looking for some light reading. Something that was decidedly not a text book; escapism while falling asleep. In my search of the shelves I eventually stumbled onto a volume entitled I See by my Outfit authored by Peter S. Beagle. It turned out that Beagle was already moderately well known for his rather macabre first novel, A Fine and Private Place -- don’t confuse that one with the Ellery Queen mystery bearing the same title -- and was probably even better known for his second novel, The Last Unicorn, which, according to one science fiction poll was named the fifth all-time best sci/fi novel ever. But when I wandered into the library that day I had read neither of those books, nor had I heard of Peter Beagle. And my eye had been caught by a non-fiction work Beagle published between those two early novels. What the Hell. I checked it out.

I See by my Outfit is an account of a trip that is easy to describe but (as Beagle demonstrated) difficult in the execution. It recounts the adventures, encounters and reflections of Beagle and his close friend Phil Segunick as they purchase matching Vespa motorbikes and then proceed to ride them from New York City to San Francisco, all so that Beagle can reconnect with his girlfriend. The title? It derives from the ballad Streets of Laredo and, more specifically, from the Smothers Brothers’ parody of that song, which Peter Beagle and his companion sing out as they take off across America on their sputtering scooters: I see by your outfit, that you are a cowboy . . . . Get yourself an outfit and be a cowboy too.

So that is the premise. But what the book is about is two young hippy kids who forsake everyday obligations and take off in an ill-thought out adventure. And in doing so they discover America -- the good, the bad, the beautiful, the ugly.

As a college student trying to figure out what I needed to do to make something of myself this turned out to be seminal escapism. I couldn’t put the book down, and though I do not own a copy I remember it well to this day. As a youngster still learning the tools needed to successfully join the rat-race of life what could be more tempting than this romance about folks my age who on a whim decided to hit the open road? The idea of just chucking it all. Not worrying about next year let alone the next decade. Forgetting about college. Forgetting about Nixon and Viet Nam. Just getting on a friendly little Vespa and cruising down those long open highways.

As a college student trying to figure out what I needed to do to make something of myself this turned out to be seminal escapism. I couldn’t put the book down, and though I do not own a copy I remember it well to this day. As a youngster still learning the tools needed to successfully join the rat-race of life what could be more tempting than this romance about folks my age who on a whim decided to hit the open road? The idea of just chucking it all. Not worrying about next year let alone the next decade. Forgetting about college. Forgetting about Nixon and Viet Nam. Just getting on a friendly little Vespa and cruising down those long open highways.

I See by my Outfit, never a best seller even in its time, is a now an obscure example of road trip literature. It's still out there, though. Centro Books re-issued Beagle’s coming of age travelog in paperback in 2007, and finally, as of last November, it is also available as a Kindle e-book.

Looking for something more recent? Perhaps a road trip tale that serves up a little crime and mystery along the way? My SleuthSayers colleague Art Taylor’s newly published On the Road with Del & Louise: A Novel in Stories is at the top of my “to read” list. In fact, it's already loaded on my tablet, stowed safely in my overnight bag behind the front seat. And all of Art's interconnected stories, as the title suggests, take place on the road.

So all of this is on my mind as I drive southwest on I-81. Back in the 1960s as tempted as I was by I See by my Outfit I couldn’t make myself do it. There was college, then law school, then the career. And there was family, and there were kids. But that freedom I lacked then I now have in retirement. You just have to be lucky enough to live long enough. Also on my mind, though, is the highway itself, and the network of other interstate highways that criss-cross America making all of our road trips, real or virtual, possible.

I think back to a story my father used to tell. He was born in 1916 -- yikes! 100 years ago. This story probably dates from the early 1920s, when he was a small child. He grew up in St. Louis, but his family previously came there from Vandalia, Illinois, about 75 miles to the east. They had always visited Vandalia relatives by train, but there came a time when his father, my grandfather, decided that the trip could be done by automobile. They decided to give it a try.

According to my father the family started out from St. Louis early in the morning, without a map, heading east across the Mississippi. After the vaguely familiar streets of East St. Louis, Illinois had been put behind them they were in the unknown. Every few miles my grandfather would slow down, hail someone by the side of the road and ask how to get to Vandalia. The roadside sage would stroke his chin and opine on the road to follow, at least for the next few miles. When those directions had been followed (or discarded as ill-advised) my grandfather would hail the next person he saw road-side and repeat the question.

According to my father the family eventually reached Vandalia -- again, 75 miles away -- just over 13 hours after they had departed St. Louis. It is, however, unfair to blame all of this directly on bad directions and the meandering roads of rural America in the 1920s. Some of the delay was more indirect -- resulting from the eight blown tires that my grandfather had to repair roadside along the way.

According to my father the family started out from St. Louis early in the morning, without a map, heading east across the Mississippi. After the vaguely familiar streets of East St. Louis, Illinois had been put behind them they were in the unknown. Every few miles my grandfather would slow down, hail someone by the side of the road and ask how to get to Vandalia. The roadside sage would stroke his chin and opine on the road to follow, at least for the next few miles. When those directions had been followed (or discarded as ill-advised) my grandfather would hail the next person he saw road-side and repeat the question.

According to my father the family eventually reached Vandalia -- again, 75 miles away -- just over 13 hours after they had departed St. Louis. It is, however, unfair to blame all of this directly on bad directions and the meandering roads of rural America in the 1920s. Some of the delay was more indirect -- resulting from the eight blown tires that my grandfather had to repair roadside along the way.

|

| The Madonna of the Trail statue in Vandalia, Illinois. (In front of the first Illinois capitol building) |

Such was the state of our roads 100 years ago, and that is what Captain Dwight Eisenhower, as recounted in the quote above, encountered when he was ordered in 1919 to see if it was actually possible as a practical matter to drive coast to coast from east to west. Most of the roads Eisenhower traversed were two lane pavement laid over the original trails connecting adjacent towns.

Vandalia was actually pretty lucky as it happens -- it was situated at the end of the National Road, the first major highway constructed by the Federal Government that had some sense to it. The road followed the Old National Trail that began in Cumberland, Maryland and was the route traveled by settlers headed west. In towns spread out along the trail, you can still find “Madonna of the Trail” statues, one in each state, commemorating those pioneers. One stands, to this day, in Vandalia.

Vandalia was actually pretty lucky as it happens -- it was situated at the end of the National Road, the first major highway constructed by the Federal Government that had some sense to it. The road followed the Old National Trail that began in Cumberland, Maryland and was the route traveled by settlers headed west. In towns spread out along the trail, you can still find “Madonna of the Trail” statues, one in each state, commemorating those pioneers. One stands, to this day, in Vandalia.

Construction of the National Road was begun in 1811, and ended in 1837 when the road had reached Vandalia. The plan was to continue the project until the National Road reached St. Louis -- which would have made things easier for my grandfather -- but the panic of 1837 and the resulting national financial collapse put an end to those ambitions. So there was some order and logic to the route when a traveler attempted to drive from the beginning of the road, in Cumberland Maryland, to Vandalia. But after Vandalia, on the roads my family drove in the 1920s, anarchy reigned.

Aside from the National Road, and a few other similar national projects, roads in the United States were originally constructed mostly at the whim of localities -- black top and portland cement strips of two lanes, climbing every hill, dropping into every valley, skirting property lines and connecting nearby towns as best they were able. There were virtually no roadside signs, and there were few maps. And that was the transportation chaos that Eisenhower encountered in 1919 when he was charged with determining whether a coast to coast automobile road trip was feasible.

Aside from the National Road, and a few other similar national projects, roads in the United States were originally constructed mostly at the whim of localities -- black top and portland cement strips of two lanes, climbing every hill, dropping into every valley, skirting property lines and connecting nearby towns as best they were able. There were virtually no roadside signs, and there were few maps. And that was the transportation chaos that Eisenhower encountered in 1919 when he was charged with determining whether a coast to coast automobile road trip was feasible.

|

| The National Road |

Things did improve. The National Road, with Federal help, became U.S. 40, and it did finally reach St. Louis and beyond. Highways 50 and 66 managed to span the country. But those United States roadways in the 1940s and 1950s were still difficult, at best.

Eisenhower noted all of this, and never forgot his 62 day transcontinental road trip. It’s a shame he didn’t record his journey. It would have been a great addition to our literature of the road.

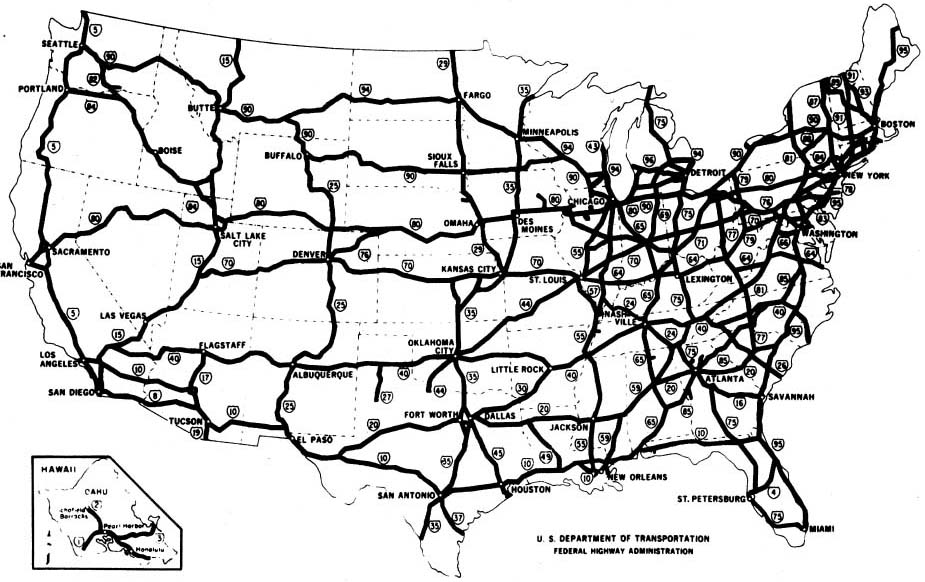

In any event, when Eisenhower commanded the Allied forces in World War II he had the personal experience from which to compare the German autobahn network with our congeries of two lane asphalt. Eisenhower knew that we needed to profit from the European approach to road building, and some ten years later as President he was finally in a position to do something about it. Largely through his efforts Congress passed the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956 and, once signed into law, the United States embarked on the greatest public works project in history -- the design and construction of the national Interstate Highway System. Funded by a Federal gasoline tax, the Interstate Highway System now ecompasses some 46,000 miles of dual lane limited access highways, connecting us as a nation.

|

| The Interstate Highway System |

We live with and on the Interstate Highway System, and we have for 50-some years. Given this, it is difficult, sometimes, not to become complacent. We are tempted to act as though these highways were always here. But Eisenhower’s vision made a huge difference for America then and now. Here’s how the History Channel summarizes it:

Today, there are more than 250 million cars and trucks in the United States, or almost one per person. At the end of the 19th century, by contrast, there was just one motorized vehicle on the road for every 18,000 Americans. At the same time, most of those roads were made not of asphalt or concrete but of packed dirt (on good days) or mud. Under these circumstances, driving a motorcar was not simply a way to get from one place to another: It was an adventure. Outside cities and towns, there were almost no gas stations or even street signs, and rest stops were unheard-of. “Automobiling,” said the Brooklyn Eagle newspaper in 1910, was “the last call of the wild.”

There are ongoing debates today about whether, and how, we can continue to fund the marvelous infrastructure of highways connecting our towns and cities. The Federal Highway Trust Fund, the source for building and maintaining the Interstate Highway system, is supported by the gasoline tax, which sits now at 18.4 cents for each gallon of gasoline purchased. That rate has not risen since the Clinton administration. In the intervening years inflation has taken its toll. And, ironically, as we continue to build more efficient cars fewer gallons of fuel are used, so fewer per gallon taxes are collected. All of this at a time when the highways, now often more than half a century old, are in need of infrastructure investments. Whether, and how, that problem can be solved is a debate for elsewhere, not here. But suffice it to say that maintaining the highway system we have built will only become more difficult. In 2008, for the first time, the Federal Highway Trust Fund, fueled by that gasoline tax, was in the red. And without additional funding that deficit will continue and will grow every year.

Those concerns aside, it is still our luck now -- today -- to be able to freely roam these united States on our own, behind the wheel. Unshackled, we can live and write about the experience. So, for the road trips we take, and the road trips we write about

Those concerns aside, it is still our luck now -- today -- to be able to freely roam these united States on our own, behind the wheel. Unshackled, we can live and write about the experience. So, for the road trips we take, and the road trips we write about

-- here's to you, Ike!

I'm on I-75 now; I-81 is well astern. Is that Chattanooga up ahead? 'Bout time to call it a day.