"Anachronism," according to Webster's:

1

: an error in chronology; especially : a chronological misplacing of persons, events, objects, or customs in regard to each other

2

: a person or a thing that is chronologically out of place; especially : one from a former age that is incongruous in the present

3

: the state or condition of being chronologically out of place

As I mentioned at the close of my last blog entry, one of the thorniest issues facing those who enjoy historicals today is the notion of the so-called "anachronistic character." While there are other challenges (a few of which I mentioned in my last post), this one might be the most difficult for historical authors to navigate, and for a whole host of reasons. Here are a few.

Author Bias

This one's a killer, in part because it can be a completely unconscious thing. You'll see it every now

and again in mainstream fiction, with the so-called "wish fulfillment" protagonist.

Now, before I delve any further into this subject, let me state up front that I have no intention of giving specific examples from amongst the ranks of writers of historical fiction (so for many of you hoping I'll dish the dirt and name names, that's your cue to stop reading now).

However, screenwriters are fair game. So let me pick up a few examples from Hollywood that ought to cause your eyes to roll and roll and roll.

A few years back the author who writes a wish-fulfillment version of themselves as their protagonist (and they are out there, and I am not naming names!) was heavily satirized in Her Alibi, a comedy starring Tom Selleck and Paulina Porizkova. The film itself is charming if uneven, and without doubt the funniest parts come with Selleck reading (in voiceover) passages from the novels his character writes, featuring a chiseled, perfect avatar of himself called "Swift."

But this is intentional, played for laughs.

Let's move on to something not intended to be funny.

Let's move on to Mel Gibson, the anachronistic.

Take his movie Braveheart (PLEASE!).

In this movie Gibson plays legendary Scottish hero William Wallace, famous for leading Scottish resistance to the predatory aims of King Edward I (called by turns, "Longshanks" because of his great height, and the "Hammer of the Scots," because, you know, conquest.).

The real William Wallace was minor aristocracy. The one Gibson portrays in this movie was practically a democrat. And his understanding of the fetish word "FREEDOM" would do a modern tea partier proud.

He's pals with people from all walks of life, dresses like a peasant, and not at all touchy about his social standing. How much he resembled the real life Wallace we have no way of knowing, but he sounds nothing like your typical class-conscious medieval aristocrat to me.

This is without doubt intentional. After all, the audience is more likely to identify with a protagonist who resembles them in their attitudes and prejudices. Leave it for the fictional English villains (BOO! HISSSSSSSS!) to be uppity and touchy about their ranks and privileges.

Nevermind that this sort of attitude tended to be a common trait among aristocrats at the time,

regardless of country of origin. Democrats and Republicans they were not. As a rule members of the upper classes during this period tended to think a lot about God, quite a bit about their immediate feudal lord (to whom they owed direct allegiance) and very little about their king.

There was no such thing as a "nation-state," at this time, and only the vaguest of notions as to the difrerence between one's county (or, if you prefer, "shire") and one's country.

And while it was true that the Scots eventually coalesced into a rough alliance against the English invaders, culminating in winning back Scottish independence at the battle of Bannockburn in 1314 (long after Wallace's execution in 1305), they were just as likely to ally against each other, highlander versus lowlander, during this period.

I see this sort of thing all the time in historical mysteries: protagonists who are far too modern in their attitudes and sensibilities to be believable as denizens of the time periods in which their authors place them.

And this is a shame, because so many wonderful historical authors get these sorts of things right! Here I am happy to name names. Medievalists such as Jeri Westerson, Michael Jecks, and Candance Robb, writers who focus on the ancient world such as Steven Saylor and Ruth Downie, Victorians and Edwardians like Tasha Alexander and Kenneth Cameron, committed generalists such as the great Edward Marston, and those who focus on the early 20th century, such as Charles Todd and Rennie Airth.

If you're gonna read historicals (and you SHOULD), why not read authors such as these who accomplish that most difficult of the historical author's labors: causing the reader to feel sympathy toward someone from a different time, who thinks differently, acts differently and likely sees the world VERY differently from we modern readers.

No mean feat, that!

Feel free to weigh in using our comments section and add the names of those historical fiction authors you think of as "getting their history right"!

As I mentioned at the close of my last blog entry, one of the thorniest issues facing those who enjoy historicals today is the notion of the so-called "anachronistic character." While there are other challenges (a few of which I mentioned in my last post), this one might be the most difficult for historical authors to navigate, and for a whole host of reasons. Here are a few.

Author Bias

This one's a killer, in part because it can be a completely unconscious thing. You'll see it every now

|

| Every writer of fiction ought to watch this one at least once! |

Now, before I delve any further into this subject, let me state up front that I have no intention of giving specific examples from amongst the ranks of writers of historical fiction (so for many of you hoping I'll dish the dirt and name names, that's your cue to stop reading now).

However, screenwriters are fair game. So let me pick up a few examples from Hollywood that ought to cause your eyes to roll and roll and roll.

A few years back the author who writes a wish-fulfillment version of themselves as their protagonist (and they are out there, and I am not naming names!) was heavily satirized in Her Alibi, a comedy starring Tom Selleck and Paulina Porizkova. The film itself is charming if uneven, and without doubt the funniest parts come with Selleck reading (in voiceover) passages from the novels his character writes, featuring a chiseled, perfect avatar of himself called "Swift."

But this is intentional, played for laughs.

Let's move on to something not intended to be funny.

Let's move on to Mel Gibson, the anachronistic.

Take his movie Braveheart (PLEASE!).

In this movie Gibson plays legendary Scottish hero William Wallace, famous for leading Scottish resistance to the predatory aims of King Edward I (called by turns, "Longshanks" because of his great height, and the "Hammer of the Scots," because, you know, conquest.).

The real William Wallace was minor aristocracy. The one Gibson portrays in this movie was practically a democrat. And his understanding of the fetish word "FREEDOM" would do a modern tea partier proud.

He's pals with people from all walks of life, dresses like a peasant, and not at all touchy about his social standing. How much he resembled the real life Wallace we have no way of knowing, but he sounds nothing like your typical class-conscious medieval aristocrat to me.

This is without doubt intentional. After all, the audience is more likely to identify with a protagonist who resembles them in their attitudes and prejudices. Leave it for the fictional English villains (BOO! HISSSSSSSS!) to be uppity and touchy about their ranks and privileges.

Nevermind that this sort of attitude tended to be a common trait among aristocrats at the time,

There was no such thing as a "nation-state," at this time, and only the vaguest of notions as to the difrerence between one's county (or, if you prefer, "shire") and one's country.

And while it was true that the Scots eventually coalesced into a rough alliance against the English invaders, culminating in winning back Scottish independence at the battle of Bannockburn in 1314 (long after Wallace's execution in 1305), they were just as likely to ally against each other, highlander versus lowlander, during this period.

I see this sort of thing all the time in historical mysteries: protagonists who are far too modern in their attitudes and sensibilities to be believable as denizens of the time periods in which their authors place them.

And this is a shame, because so many wonderful historical authors get these sorts of things right! Here I am happy to name names. Medievalists such as Jeri Westerson, Michael Jecks, and Candance Robb, writers who focus on the ancient world such as Steven Saylor and Ruth Downie, Victorians and Edwardians like Tasha Alexander and Kenneth Cameron, committed generalists such as the great Edward Marston, and those who focus on the early 20th century, such as Charles Todd and Rennie Airth.

If you're gonna read historicals (and you SHOULD), why not read authors such as these who accomplish that most difficult of the historical author's labors: causing the reader to feel sympathy toward someone from a different time, who thinks differently, acts differently and likely sees the world VERY differently from we modern readers.

No mean feat, that!

Feel free to weigh in using our comments section and add the names of those historical fiction authors you think of as "getting their history right"!

|

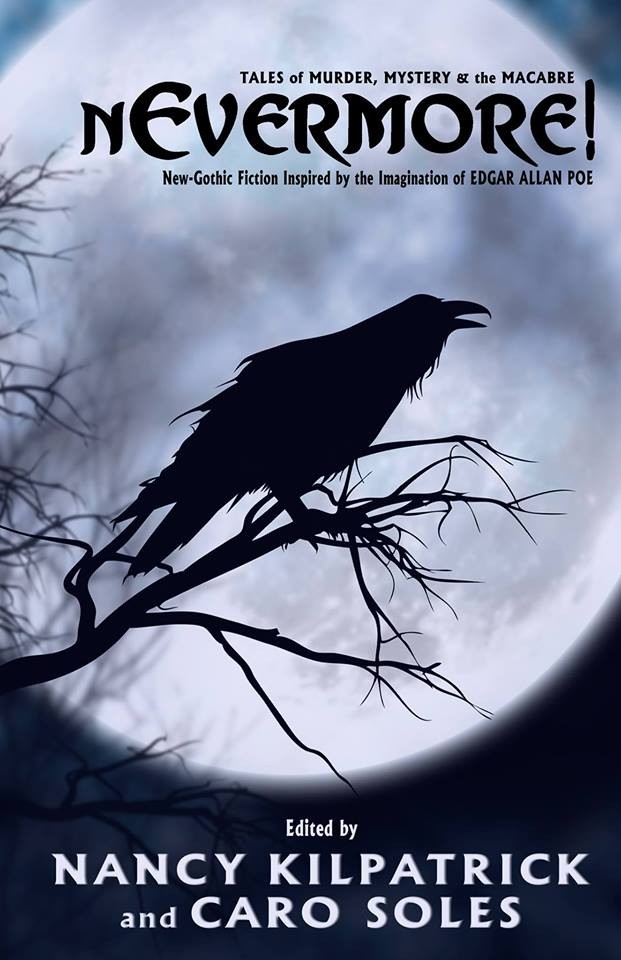

| And don't even get me started on what's wrong with THIS one.... |

Gayle Lynds has done it to me again. Her new thriller, The Assassins, a July release from St. Martin's Press, opened, grabbed me by the throat and kept me up late two nights in a row. As much as I love sleep, this is a superb read and one missing a few hours of sleep over.

Gayle Lynds has done it to me again. Her new thriller, The Assassins, a July release from St. Martin's Press, opened, grabbed me by the throat and kept me up late two nights in a row. As much as I love sleep, this is a superb read and one missing a few hours of sleep over.