Now I have a theory that there is something about baseball that makes it fuel for great novels and great movies, in a way that no other sport seems to do. Granted, every sport has at least one fantastic book and/or movie based on it. And before you start screaming about why I didn't include certain movies, I know that every sport has its dying player movie (Brian's Song v. Bang the Drum Slowly, James Caan v. Robert DeNiro, for example, take your pick), and its unusual and/or unlikable and/or unbeatable coach movie (often ad nauseum, make your own list). And the occasional one with animal players, often monkeys (Every Which Way But Loose leaps to mind). SO:

SURFING (my second favorite sport to watch - can you tell I'm a California girl?): Endless Summer, of course, and Riding Giants. (And, just for a time capsule and a so-bad-its-good movie, Gidget.)

SURFING (my second favorite sport to watch - can you tell I'm a California girl?): Endless Summer, of course, and Riding Giants. (And, just for a time capsule and a so-bad-its-good movie, Gidget.)BASKETBALL: Hoosiers, Hoop Dreams, and He Got Game.

FOOTBALL: Friday Night Lights, book, movie and show. But my personal guilty pleasure is, Semi-Tough by Dan Jenkins, sadly made into an incredibly bad movie in the 70's.

(NOTE to Dan Jenkins: get Kevin Smith to direct a new version of Semi-Tough, PLEASE, because he's the only director I can think of that could do justice to your profanity-laced, sex-sodden, really f---ing hilarious take on football, rivalry, and true love. You do that, and it might wash the taste of that Michael Ritchie version out of my mind...)

ICE HOCKEY: Slapshot.

Now these are good, but if you want depth, I think there are only two sports that really bring it out: baseball and boxing.

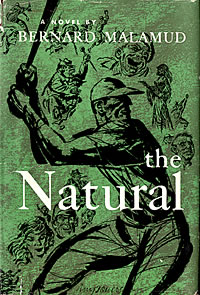

The Natural by Bernard Malamud. Forget the movie version, though it's good in its own way. The novel is raw and angry and sad and an allegory of life from the point of view of all of us who have screwed at least one thing up so badly it will never come right or have had fate step in and snatch everything away just as we had it in our hand:

The Natural by Bernard Malamud. Forget the movie version, though it's good in its own way. The novel is raw and angry and sad and an allegory of life from the point of view of all of us who have screwed at least one thing up so badly it will never come right or have had fate step in and snatch everything away just as we had it in our hand:"Roy, will you be the best there ever was in the game?" "That's right." She pulled the trigger...

"We have two lives; the life we learn with and the life we live after that."

Back when I put myself through college teaching ESL, we used The Natural to teach our Puerto Rican baseball scholarship students in order to get them to read - and it worked. It also broke (some of) their adolescent, ambitious little hearts. Great book. Good movie.

You Know Me Al by Ring Lardner. A collection of short stories, all letters from the road, penned by Jack Keefe, the dumbest, greediest, most cluelessly self-absorbed pitcher the Chicago White Sox ever had. I don't think even Will Farrell could capture Jack Keefe, because he is... just read it and laugh your head off. (NOTE: Ring Lardner ranks as one of the greatest short story writers of all time, imho, if nothing else for these and "Haircut" and "The Golden Honeymoon")

Shoeless Joe by W. P. Kinsella. Read it, please. And, yes, go get the movie. I hold my breath through half the movie, and then cry shamelessly (usually after the appearance of Burt Lancaster) every time I see the damn thing.

Eight Men Out by Eliot Asinof and Stephen Jay Gould. A meticulous, well-written, time capsule of the time and events of the worst baseball scandal in history. The movie isn't any slouch, either, directed by John Sayles with a strong, strong cast, especially D. B. Sweeney as Shoeless Joe Jackson and Studs Terkel as sportswriter Hugh Fullerton.

Speaking of baseball movies, here's a few, in no particular order:

Bull Durham

The Pride of the Yankees

Damn Yankees (whatever Lola wants...)

Ken Burns' Baseball

A League of Their Own

The Rookie

The Babe Ruth Story

Bingo Long Traveling All-Stars and Motor Kings

Now I said baseball and boxing, and first of all, here are some great boxing movies:

Raging Bull. Rocky. Requiem for a Heavyweight. When We Were Kings. The Harder They Fall.

But baseball players and boxers are right out there, for us all to see. And both boxing and baseball movies and novels tend to focus on individual heroism and/or failure. Both sports allow an individual to take center stage, to let us get to know them, and then watch them sink or swim. We can make emotional connections. And they can be made into allegories that almost everyone can relate to.

Or at least that's my theory. Meanwhile, I've got to get out to the ballpark!