(This week's entry continues delving into the long form articles I did while researching and writing The Book of Ancient Bastards (Adams Media, 2011). A shorter version of this bit about one of Rome's more "original" rulers (and the pack of relatives who descended on Rome along with him) appeared in that book.)

I will not describe the barbaric chants which [Elagabalus], together with his mother and grandmother, chanted to [Elagabal], or the secret sacrifices that he offered to him, slaying boys and using charms, in fact actually shutting up alive in the god’s temple a lion, a monkey and a snake, and throwing in among them human genitals, and practicing other unholy rites.

— Dio Cassius

If you’re going to catalogue historical bastardry throughout the ages, you’d better plan to touch on that colorful period in the historical record known as “Imperial Rome.” As with the Papacy, the sheer number of men who wore the emperor’s purple robes over the empire’s five-plus centuries lends itself to the likelihood that the throne would occasionally be occupied by someone so “eccentric” that he stood out in a crowded field of “personalities” like Michael Jordan playing basketball with a bunch of kindergarteners.

Ladies and gentlemen, meet Varius Avitus Bassianus, a young, Syrian-born aristocrat who ruled the empire under the very Roman-sounding name of “Marcus Aurelius Antoninus” from 218 to 222 A.D., but was better known by the nick-name “Elagabalus.”

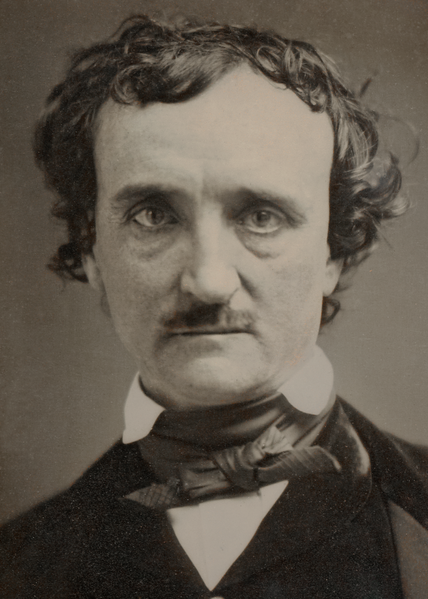

|

| What "El Gabal" probably looked like pre-deification |

| Funny, he looks so....normal... here.... |

And that’s just the tip of the iceberg (or, if you prefer, the meteorite).

Elagabalus was a shirt-tail relation of the great (and ruthless) emperor Septimius Severus. His grandmother was Severus’ sister-in-law. When Severus’ direct line died out (and the story of how that all played out is grist for a future blog post), Elagabalus’ grandmother (Julia Maesa) and mother (Julia Soaemias) schemed along with a eunuch named Gannys to put the boy forward as a plausible claimant to the imperial throne.

| An ancient "Mommie Dearest," Julia Soeamias |

When he got there he made quite a splash, not least because he brought his god with him.

Literally.

This massive “sky stone” was ensconced in a new temple complex built expressly for it, right next to the old Flavian Amphitheatre (what we know today as the “Colosseum”) on Rome’s Palatine Hill, and named the “Elagaballium.”

During Rome’s annual Midsummer Day festival, the ancient writer Herodian reports:

[Elagabalus] placed the sun god in a chariot adorned with gold and jewels and brought him out from the city to the suburbs. A six-horse chariot carried the divinity, the horses huge and flawlessly white, with expensive gold fittings and rich ornaments. No one held the reins, and no one rode with the chariot; the vehicle was escorted as if the god himself were the charioteer. Elagabalus ran backward in front of the chariot, facing the god and holding the horses’ reins. He made the whole journey in this reverse fashion, looking up into the face of his god.

As if that weren’t shaking things up enough for his new subjects, Elagabalus promptly swept aside the old Roman pantheon of gods, and “married” his god Elagabal to the Roman goddess Minerva. As a mortal “echo” of this Heavenly union Elagabalus then did the truly unthinkable: he took one of Rome’s Vestal Virgins as his wife. Dedicated to the Roman mother goddess Vesta, whose service obliged these priestesses to remain virgins during their twenty years of service. If one of them didn’t, the punishment was for her to be buried alive. And Elagabalus took one of them, a woman named Aquilia Severa as his wife not once, but twice!

In the four years he was emperor Elagabalus took at least three different women as his wife. These marriages were likely arranged by his grandmother and mother (“the Julias”) in order to help preserve the fiction that “Imperator Marcus Aurelius Antoninus” was a solid, dependable Roman citizen and emperor, rather than the capricious Syrian drag-queen high-priest of a bloody-thirsty sun-worshipping cult. It was hoped that keeping up this appearance would help cement support for his reign. In fact, these two formidable women proved themselves to be particularly shrewd and capable administrators.

Put simply, things ran so smoothly in Rome and throughout the empire that for a while people didn’t seem to mind how much of a “free spirit” their emperor appeared to be.

And a “free spirit” he definitely was. Although Romans had tolerated the tendency among some of their previous emperors to take male lovers, homosexuality in ancient Rome was by and large frowned upon. Elagabalus flouted this attitude by taking as his “husband” a big, burly slave from Caria; a charioteer of some skill named Hierocles. One of his favorite roles to play was that of the “cheating wife,” allowing himself to be “caught” in bed with another man by Hierocles, who then beat the emperor (who apparently enjoyed “rough trade”), at times so badly that ‘he had black eyes’ for days afterward.

Probably transsexual, Elagabalus seemed obsessed with becoming more like a woman, not with just taking men to bed. The Historia Augusta reports that the emperor “had the whole of his body depilated,” and according to the disapproving contemporary historian and senator Dio Cassius, Elagabalus “had planned, indeed, to cut off his genitals altogether,” but settled for having himself circumcised as “a part of the priestly requirements” of his cult.

By the time Elagabalus turned seventeen his continual nose-thumbing at Rome’s religious, social and sexual norms began to take a toll on his public image. In 221 two different legions mutinied and just barely missed proclaiming their respective generals “augustus” (“emperor”) in his stead.

This unrest did not escape the attention of Elagabalus’ grandmother, the Augusta Julia Maesa. Her hold on the levers of power depended on her grandson staying in the good graces of both the people and army, and his increasingly erratic behavior and eroding popularity with his subjects made the dowager empress very nervous.

She opted to advance Bassianus Alexianus, another of her grandsons, as Elagabalus’ co-ruler and

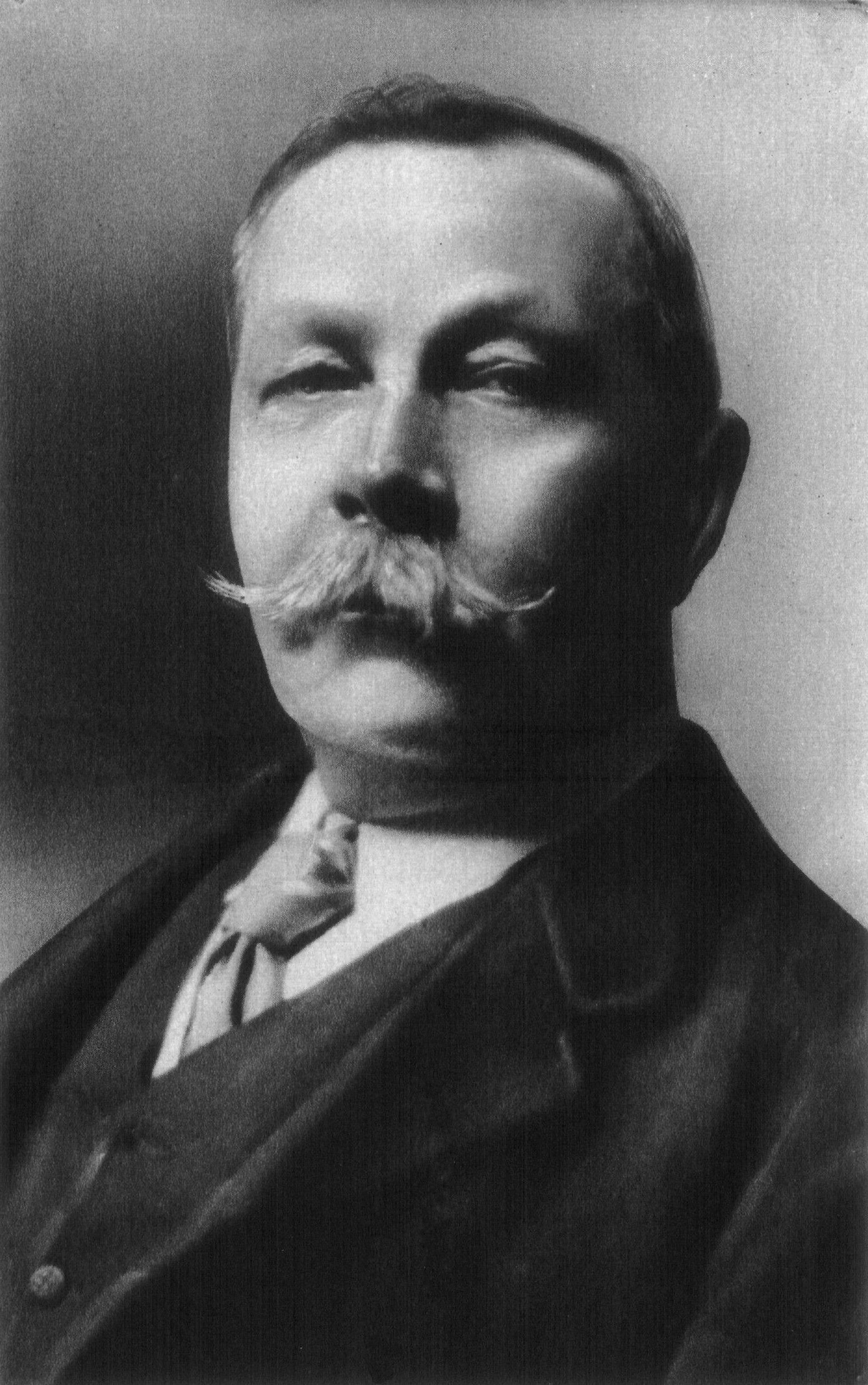

|

| Severus Alexander |

At first Elagabalus and his mother went along with the move. Within weeks, however, the senior emperor had changed his mind and tried to have his younger cousin killed. A power struggled ensued. The modest, retiring Alexander was popular with the people, and especially with the army.

|

| Julia Mamea |

It all finally came to a head in March of 222, when Elagabalus flew into a rage during a meeting with the commanders of his personal bodyguard (the Praetorian Guard, which also acted as the city of Rome’s police force). Having been reminded again and again of the “virtues” of his younger cousin, Elagabalus once more called for Alexander’s arrest and execution, bitterly denouncing the Praetorians for preferring his cousin to himself.

It was not a smart thing to do this while still standing in the middle of their camp.

| |

| Praetorian in full armor |

Later historians (especially Christians) whipped up improbable tales of human sacrifice conducted by this teenaged demagogue, and speculated wildly about the various depravities in which he might have indulged. This speculation included the unlikely story of how “Heliogabalus” (sic) invited several very important people to a dinner party only to have them smothered to death under the weight of several hundred pounds of flowers. This painting trades upon that myth.

| A 19th century artist's conception of Elagablus' supposed use of flowers to smother party guests |