"You have often heard [Washington] compared to Cincinnatus. The comparison is doubtless just. The celebrated General is nothing more at present than a good farmer, constantly occupied in the care of his farm and the improvement of cultivation."

– French traveller Jacques-Pierre Brissot de Warville after visiting Mount Vernon in 1788

|

| Washington and Lafayette at Mount Vernon, circa 1784 |

“Tis a Conduct so novel, so inconceivable to People, who, far from giving up powers they possess, are willing to convulse the Empire to acquire more.”

– American painter and former Washington military aide-de-camp John Trumbull, on Washington's resignation of his command, 1784

|

| General Washington resigning his commission before Congress in December, 1783, by John Trumbull |

"There are decades where nothing happens; and there are weeks where decades happen."

–Vladimir Ilyich Lenin (attr.)

Good Morning Fellow Sleuthsayers, and Happy August!

And I say this with a July for the Ages just barely in the record books. You hear this sort of thing all the time: "One for the record books." "This is unprecedented," etc., especially in this era of big media covering something as consequential as the election of the most powerful person on the planet as if were the fifth race at the dog track. Usually it's hyperbole.

Not this time, my friends.

Now, no matter your political persuasion, this ought to interest you, especially if you're any of the following:

- A human being.

- A lover of history.

- Concerned about the world you might be leaving for your kids/grandkids, etc.

- Just love a good story.

So with the assistance of Axios and NBC News, let's timeline this past month and a bit:

June 27, 2024

Debate between President Biden and former president Trump. Biden does poorly.

July 2, 2024

Rep. Lloyd Doggett of Texas becomes the first Democratic congressman to publicly call for President Biden to withdraw from the presidential race.

July 3, 2024

Big Democratic donors including Reed Hastings call on Biden to step aside.

July 5, 2024

George Stephanopoulos interviews President Biden.

July 10, 2024

Senator Peter Welch of Vermont becomes the first Democratic senator to publicly call for President Biden's withdrawl from the presidential race.

July 11, 2024

President Biden accidentally calls Ukrainian President Zelensky "President Putin" and Vice President Harris "Vice President Trump" ahead of a NATO presser.

July 13, 2024

Assassination attempt on former president Trump's life at Pennsylvania rally.

July 15, 2024

Former president Trump announces Senator JD Vance of Ohio as his vice presidential running mate.

July 17, 2024

President Biden tests positive for COVID. Rep. Adam Schiff of California publicly calls for President Biden to withdraw from the presidential race.

July 18, 2024

Rambling, and at times barely coherent, former president Trump formally accepts the Republican nomination for president, with a record length 90-plus minute speech.

July 19, 2024

President Biden reiterates that he will stay in the race as at least 25 additional lawmakers call for him to step aside. NBC News breaks the story that members of President Biden's family have discussed what an exit from his campaign might look like.

July 20, 2024

Former speaker of the House of Representative Nancy Pelosi meets privately with President Biden, and informs him that in her opinion and based on available polling data, he cannot defeat former president Trump in the coming election, and and risks killing the Democrats' chances of holding the Senate and re-taking the House. Biden is defiant in response.

July 21, 2024

President Biden announces he will leave the presidential race and immediately endorses Vice President Harris to be the party's nominee. All but a few of his closest aides have no idea he will leave the race until mere minutes before he posts a press release on Twitter announcing his withdrawal.

* * *

Twenty-four days? Feels like twenty-four years! Which is why I included the Lenin quote (something he may or may not have actually said. Historians differ on this point.). And I'll skip the following ten days, with the rise of Kamala Harris as the party's nominee, the excitement it has generated, the party and many previously disaffected supporters energized and heartened by the quick coalescing of support around Vice President Harris, and the concomitant floundering of former president Trump's candidacy.

That story has yet to play out, and nothing is certain. So I'll write about that at some point after a certain Tuesday in the coming November.

After all, it's really beside the point of this post.

That point? The "Cincinnatus" factor.

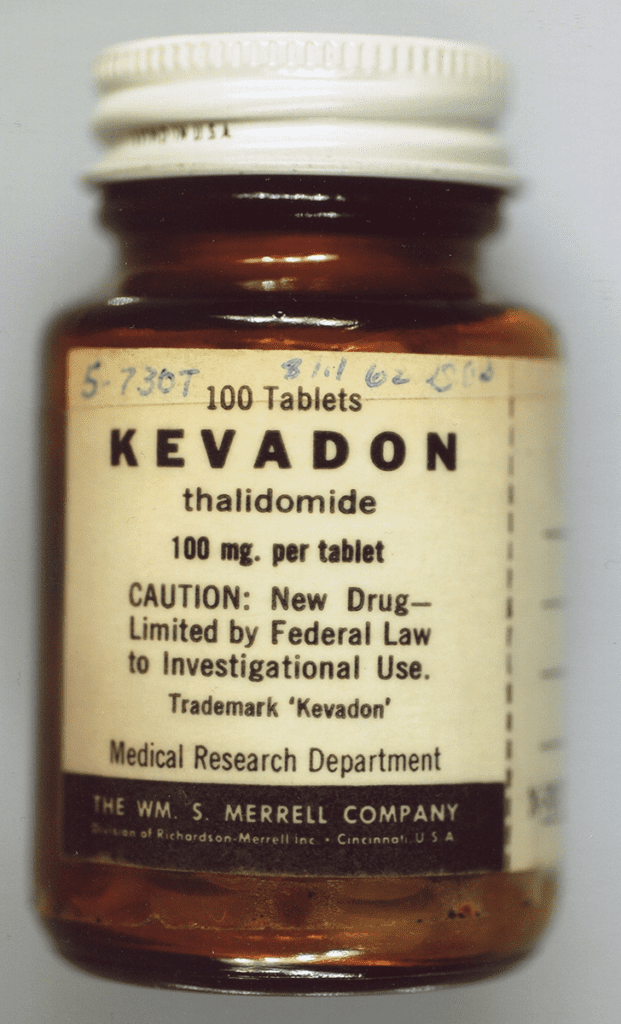

Yes, that's right, not "Cincinnati." "Cincinnatus." Don't get me wrong. Cincinnati's a great city. It's the home of so many terrific things: the Reds, its own namesake variant on traditional chili, goetta, Graeter's Ice Cream, Play-Doh, Preparation-H, Aspercreme, the first truly German-descended beers brewed in America, and of course, long-time friend and fellow Sleuthsayer, Jim Winter (Hi Jim!).

But for the purposes of this conversation, "Cincinnati" will refer to a fellowship aligning itself with tradition of a "Cincinnatus," rather than to the city named in honor of one such worthy.

So what is this "factor" I have dubbed the "Cincinnatus" factor?

Simple: it's the notion that one of the highest of all civic virtues is such respect for great power as to be willing to surrender it, thereby placing the best interests of one's country above one's own selfish desires.

The word comes from the name of an ancient Roman politician and soldier named Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus (fl. 5th century B.C.). As the story comes down to us from the Roman historian Livy, Cincinnatus earned the respect of his colleagues as both a politician and as a general. Eventually, after a long career serving Rome, he retired from public life to farm a few acres (Livy says it was four acres) he owned outside the city.

Not too far into Cincinnatus' retirement, Rome found itself threatened by a powerful invasion force, with its army surrounded and all but beaten. The current consuls (officials charged with running the city and executing the laws passed by the Roman Senate) were apparently not up the task of saving either the city or its army, and so they followed Roman law which dictated (no pun intended, see next) that in time of emergency the Senate could vote to suspend the Roman constitution and place all power in the hands of a "dictator" for a term of six months.

The Senate voted and the official they chose to serve as dictator was none other than the now-retired Cincinnatus. When the members of that worthy body caught up with the man they had voted absolute power to, he was in the middle of plowing his field. Once the situation had been explained to him, Cincinnatus left his plow standing in the midst of said field, said goodbye to his wife and set off to save Rome and its army.

He was successful in both endeavors.

And it took him just over two weeks (sixteen days) to do it.

And what did he do next? Did he serve out his term and enjoy the perks of absolute power for the next five and a half months?

Nope. Once the danger had passed, Cincinnatus resigned his position and returned to his plow.

A rare move, rare among Roman dictators (see Lucius Cornelius Sulla Felix and Gaius Julius Caesar, just to name a couple who, for their own reasons, did not follow Cincinnatus' shining example), rarer still among rulers throughout the ages since the fall of Rome.

|

| You KNOW that rod is not just for show |

One need look no further than 17th century English history and the "Protectorate" government of Oliver Cromwell, which while officially a "commonwealth," was in fact nothing short of a military dictatorship. Having fought on the side of the Parliamentary forces against the king's supporters in England's recent civil war, placed at the head of Parliament's military forces, Cromwell took to being an unaccountable autocrat just as quickly as Charles I, the "divine right" king Cromwell helped defeat, depose and eventually see executed. If anything Cromwell was worse than Charles. He was a competent administrator and a shrewd judge of people, where the foppish dullard Charles Stuart was neither of these things.

And that is just one example. History is replete with stories of princes, pashas, caliphs, kings and all other sorts of rulers who, once attaining power, clung to it like grim death.

And our own modern history has its own Pinochets, its Stalins, its Hitlers (I know, too easy, but hey, if the swastika armband fits...), its Castros, its Chavezes, Its Perons, its Duvaliers, its Somozas, its Putins, its Ceaușescus, and so many more.

Which makes the example of America's own "Father of his Country" all the more remarkable.

Yes, none other than George Washington is known in many quarters as the "American Cincinnatus," and the Society of the Cincinnati is named in his honor. Why? Simple. When given the opportunity to seize and hold absolute power at the end of the American Revolution, Washington resigned his commission mere months after the ratification of the Treaty of Paris in 1783.

And then he went home to his farm.

Of course the story doesn't end there. Of course Washington was so highly regarded that he was summoned back into his country's service, first to preside over the constitutional convention intended to codify itself existence as a democratic republic, and then as the first president of that same democratic republic.

And then he did it again.

After two terms served as president, Washington willingly gave up power again, retiring from public life and refusing to serve a third term.

Instead he went home to Virginia to farm.

Is it any wonder that some of the more poetic among us refer to Washington as "the American Cincinnatus"?

It is just this example that our own current chief executive, haltingly, some would say tardily, certainly imperfectly, has so recently followed.

Joseph Robinette Biden Jr., easily already the most consequential president of my lifetime (I was born in 1965), when faced with a race he was sure he could win, combined with the failing faith of his erstwhile supporters, did a surprising thing. When his own people told him they thought it best for the nation that he serve out his single term, but step down as his party's nominee for the presidential election this year, he caviled, he argued, I'm sure he stewed and fumed and perhaps even privately raged.

And then he listened to them. And once again, Joe Biden answered his country's call.

I'm not here today to talk about the existential threat this country faces, or how President Biden's action may well have helped rescue it from said threat. I'm not here to talk politics. I'll leave it for others to do that.

I'm just here to point out that without the occasional selfless action of a Cincinnatus, any republic, any democracy, is doomed.

The Cincinnati. May our country continue to produce them.

See you in two weeks!

.jpg)