29 May 2023

How much of a misfit can a writer be?

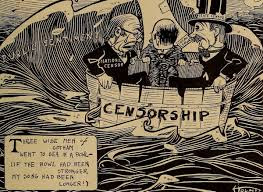

In today's publishing, there are a lot of rules based not on literary values but on the marketplace, as the industry tries to predict the unpredictable and control the uncontrollable. The underlying rip current is fear, determined by neither art nor business but by the chaotic politics of the moment. How far outside the lines am I allowed to color? As far as I want? Or only up to a limit defined by others?

In recent years I've become interested in writing from a Jewish perspective in my fiction. But anti-Semitism is on the rise globally. Jews are not getting a clear message that we're included under the sheltering umbrella of "diversity." So can I tell as many stories as I want, or just a token number? When will I be told that it's enough?

I've recently become interested in writing about trans people. I'd like to see trans characters integrated into crime fiction the way they are in speculative fiction. I have had one such story published, but I was disappointed when the editor allowed my preferred title to be vetoed by a low-level staff member who was trans. My 62-year-old nonbinary nibling (formerly my niece) commented: "I loved your title. The word police are mostly under forty."

How careful am I supposed to be with titles from now on? Will I be free to inform the development of all the characters I write with the full measure of my empathy and imagination? Does the publishing industry realize that the younger generation doesn't know anything? I remember trying to tell a young woman that the derogatory term "boujee" came from the word "bourgeois," for middle class. "No it doesn't," she said. "It's just itself." I didn't argue. People believe what they want to believe.

At this point in my life, I'm happy writing short stories. If I ever wrote another novel, it might be about two lifelong friends, a Jewish girl with Communist parents and a Black girl from Harlem with roots in what she calls a "good family" in the South, who first meet in the early1950s. But I have no incentive to write it. I wonder why not?

28 May 2023

Raising Money

by R.T. Lawton

A few years ago, my Huey pilot buddy and I sat down to see if we could brainstorm a short story. Something different than we had conjured up in the past. The result was a rough outline for a couple of young conmen who had come up with a new scheme to try out in the criminal world. Their basic premise went something like the following.

If criminals could purchase a "clean" gun for a job, then maybe they would also be interested in renting a "clean" car so as not to be nabbed in a stolen car on their way to the job. The result was "The Clean Car Company" published in the January 2021 issue of Mystery Weekly Magazine (now Mystery Magazine). Of course, the two young conmen, Danny and Jackson, ran into a couple of glitches in their plan. They hadn't expected a dead body in the trunk when the rented car was returned.

Now, it was time for the duo to try out a new scheme which was actually an old con from the streets of Harlem. Raising Money was the pitch. Find a not-too-smart mark with lots of money and convince him that you could raise money by increasing the denominations on U.S. currency through the use of the modern miracles of science and technology.

What's that, you don't believe such a feat is possible? Have you considered all the recent advances in science and technology which are difficult to explain to the common layman? Well then, let's see if you can explain to both our satisfaction how that same GPS voice in your cell phone can direct thousands of drivers along various different routes at the same time and yet still tell each driver when and where to make the correct turns to get to each one's different destinations. Or is it some sort of magic?

Perhaps you should just read "Raising Money" in the May 2023 issue of Mystery Magazine and see how the con plays out.

For those of you interested in the timeline from submission to reply to publication, here are the entries in my Submission Log:

- 03/17/23 "Raising Money" subbed to Mystery Magazine

- 03/21/23 e-mail acceptance

- 03/22/23 signed & returned e-contract

- 03/23/23 paid via PayPal

- 05/01/23 published

Oh yeah, our very own Rob Lopresti has a short story in this same May 2023 issue and his submission log entries should be about the same as mine.

27 May 2023

"Why don't you write about Gina Gallo's Grandmother?" or Where do you get your Ideas?

Ah, the timeless question. Where do you get your ideas?

I think it was Stephen King who talked about a little mail-order store in small town America...

I've never been able to find that store myself. Stephen keeps it a close secret (I hope you're smiling.)

But

I had reason to experience that dilemma about two years ago, a year

into the pandemic, and a year after my husband David died.

Damn that covid, and what it's done to publishing. When Orca Books told me that they were capping the line that carried my Goddaughter series (translation: still selling the books in the line, but closing it to future books, at least for now) I was in a tight spot.

What to

write next? I'd had 10 contracts in a row from Orca! That series

garnered three major awards! How could I leave it behind?

Put another way: what the poop was I going to write next?

The Goddaughter series featured a present day mob goddaughter who didn't want to be one. Gina Gallo had a beloved fiance who thought she had gone straight. But of course, in each book she would get blackmailed into helping the family pull off heists or capers that would inevitably go wrong. It allowed for a lot of madcap comedy.

Some would say I was a natural to write a series about a mob goddaughter (we'll just leave it at that.) And I liked the serious theme behind the comedy: You're supposed to love and support your family. But what if your family is this one?

Issues of grey have always

interested me. We want things to be black and white in life, but quite

often, they are more complex than that. I like exploring justice

outside of the law in my novels. But I digress...

The Goddaughter books brought me to the attention of Don Graves, a well-known newspaper book reviewer up here. He commiserated with the end of the Goddaughter series, and immediately suggested the following:

"Why don't you write about her grandmother? Prohibition days, when the mob was becoming big in Hamilton."

The idea burned in me. Except it wouldn't be her grandmother. (Don is older than me.) It would be her great-grandmother! Coming to age in the time of Rocco Perri and Bessie Starkman...

I settled on 1928,

because that was the year women finally got the vote in England. The

status of women features very much in this novel. The time frame also

allowed me to use the aftermath of WW1, including men like my own

grandfather, wounded by gas, and shell-shocked. I would make the

protagonist a young widow, because I knew grief - oh man, did I know

grief. My own husband had died way before his time, the year before. I

could write convincingly about that.

But I would also use bathos to lighten the tale. (I seem incapable of writing anything straight.) The comedy of the Goddaughter books finds its way into The Merry Widow Murders, and so far, has generated smiles for prepub reviewers.

The book took me over a year to write, working full time on it. It helped me to channel my grief. It forced me to step out of my comfort zone and write something with considerable depth.

And it taught me that - even widowed - I wasn't entirely alone. That ideas are beautiful things that can come from friendship, and the good hearts of readers and reviewers you are fortunate to meet along your publishing journey.

Thank you, Don!

So tell me: where do you get your ideas?

"Delightful...Not to be missed" Maureen Jennings,

author of the Murdoch Mysteries on TV

author of the Murdoch Mysteries on TV

and the Paradise Cafe series

The Merry Widow Murders

Now available!

Barnes&Noble, Chapters

Amazon, independents

and all the usual suspects

from Cormorant Books

1928, At Sea

When an inconvenient body shows up in her stateroom,

Lady Revelstoke and her pickpocket-turned-maid Elf know how to make it

disappear--and find the killer.

"Miss Fisher meets Hitchcock's The Trouble with Harry. The perfect escapist read!" Anne R. Allen

26 May 2023

They Don't Write 'Em Like That Anymore

by Jim Winter

I just finished listening to The Iliad on audio. Read by Dominic Keating of Star Trek: Enterprise fame, one got the sense one was listening to Homer riffing in front of a crowd in some Athenian public space. Keating had to read a fairly new English translation, but The Iliad and its companion piece, The Odyssey, are really epic poems. Keating's dramatic read hewed closer to Patrick Stewart or Ian McKellan doing Shakespeare. Homer, especially after listening to some of the translator's background in the intro, probably sounded like Jack Kerouac to those ancient Greeks.

Except I've read Kerouac's On the Road. Incidentally, that, too, is meant to be performed, not read. But I digress. Kerouac's prose is the beat poetry of the fifties laid over the prose of the day, which, like today, has Hemingway in its bones. He's into a scene, and he's out, and the flourishes come from spending short snatches of time in Sal Paradise's bizarre mind.

Homer, on the other hand, does things in The Iliad no editor, even the most forgiving of editors, would let out of the slush pile, let alone into print. The goddess Athena is referred to not merely as the goddess of wisdom or daughter of Zeus, nor does Homer limit himself to the epithets like Pallas Athena. No, she is "Athena, she of the bright, shining eyes." Achilles, who spends most of the story sulking in those final days besieging Troy, is "Achilles of the fleet foot." These are not one offs. Homer uses this or a similar phrase every. Single. Time.

Mind you, it's an epic poem, and Keating's reading, even after taking out the supplemental material, is almost twenty hours. (Also, Homer likely never ended with "Audible hopes you've enjoyed this program.") And we don't see a lot of epic poems these days. Even its spiritual descendant, rock's concept album, is a bit of a dinosaur. Its last adherent seems to be Roger Waters, and lately, most people wish Rog would just shut the hell up.

These days, if you're going to ramble, as Homer does without anyone really noticing, you have to be Stephen King about it. Going off on a tangent? Tell a story within the story, then circle back to the point. Most editors won't allow that these days. (And I really think current editing dogma is too rigid. Says the editor.) Otherwise, get to the point (says the guy who likes writing lean prose.) So when a character walks into a scene, the most extreme example of modern description is to find a trait, use that trait as a placeholder, and only change it when their name is revealed. Robert B. Parker did this throughout his career, but it began all the way back in The Godwulf Manuscript. The one I remember best is where Spenser's attempts to rescue Susan Silverman overlap a government black op. Spenser says the agent looks like Buddy Holly, and for a page or two, refers to him as Buddy Holly. I don't remember the guy's name or if he even had one, but I remember him, his job, and most of what he did.

Even Dickens, one of the most verbose writers in modern English, stuck with names or something descriptive, like the Artful Dodger. His name was actually Jack Dawkins, but how many Jacks are their in novels set in 19-century England or America? Hell, Jean-Luc Picard's son is named Jack, named for his half-brother's father. Sometimes, the title or job sticks better. But for all Dickens's wordiness, Artful Dodger is a short, powerful shorthand for a character in Oliver Twist. Contrast that with Dickens's American counterparts, Hawthorne and Melville. One of the reasons I found The Scarlet Letter so unreadable, at least at the age of 15, when I'd discovered King and Tom Clancy, was the constant refrain of "It seemed as though Hester Prynne..." (And in 2023, my inner editor is going, "HEY! STOP BEATING THAT DEAD HORSE!") On the other hand, Melville scores points for being more episodic in Moby Dick and hanging genius labels on Ishmael's shipmates, such as Starbuck or the cannibal (who ironically doesn't eat anyone in the story.)

Much of this is the function of the culture. Even if we write stories about Greek or Roman or Norse gods, they come off as aliens or superheroes (or supervillains) or both. Marvel built a big chunk of its mythos around Thor and Loki. As far back as Twain's era, we didn't want Athena of the Bright Shining Eyes or Zeus Who Holds the Aegis. Nowadays, we want Wonder Woman's sister or Liam Neeson shouting, "Release the kraken!"* In Homer's day and even into Shakespeare's time, we wanted heroes. Mythical heroes. Of course, until the Enlightenment, we weren't quite as sciencey as we are now. Hence, even Harry Potter has to follow some sort of rules and most conspiracy theories are based on bad science skimmed while scrolling the phone in the bathroom. When we pay closer attention, ignoring Newton and Einstein without an explanation is what writers call "a plot hole."

*Fun fact: He meant the rum, of which I have a bottle, actually. Too bad I don't drink much anymore.

25 May 2023

Setting as Character

This is a piece I wrote shortly after joining the rotation here at Sleuthsayers, just about a decade ago. Reposting at the request of an emerging writer who found helpful and thought others might as well.

********************************************************

Setting. Everyone knows about it. Few people actively think about it.

And that's a shame, because for writers, your setting is like a pair of shoes: if it's good, it's a sound foundation for your journey. If it's not, it'll give you and your readers pains that no orthotics will remedy.

Nowhere is this more true than with crime fiction. In fact strong descriptions of settings is such a deeply embedded trope of the genre that it's frequently overdone, used in parodies both intentional and unintentional as often as fedoras and trenchcoats.

Used correctly a proper setting can transcend even this role–can become a character in its own right, and can help drive your story, making your fiction evocative, engaging, and (most importantly for your readers) compelling.

Think for a moment about your favorite crime fiction writers. No matter who they are, odds are good that one of the reasons, perhaps one you've not considered before, is their compelling settings.

Just a few contemporary ones that come to mind for me: the Los Angeles of Michael Connelly and Robert Crais. The Chicago of Sara Paretsky, Sean Chercover and Marcus Sakey. Boston seen through the eyes of Robert B. Parker. Ken Bruen's Ireland. Al Guthrie's Scotland. Carl Hiassen's Miami. Bill Cameron's Portland. Sam Wiebe’s Vancouver.

And of course there are the long gone settings highlighted in the gems of the old masters. These and others read like lexical snapshots from the past.Who can forget passages like:

The city wasn't pretty. Most of its builders had gone in for gaudiness. Maybe they had been successful at first. Since then the smelters whose brick stacks stuck up tall against a gloomy mountain to the south had yellow-smoked everything into uniform dinginess. The result was an ugly city of forty thousand people, set in an ugly notch between two ugly mountains that had been all dirtied up by mining. Spread over this was a grimy sky that looked as if it had come out of the smelters' stacks.

—Dashiell Hammett, Red Harvest

Or this one from Raymond Chandler's Farewell, My Lovely:

1644 West 54th Place was a dried-out brown house with a dried-out brown lawn in front of it. There was a large bare patch around a tough-looking palm tree. On the porch stood one lonely wooden rocker, and the afternoon breeze made the unpruned shoots of last year's poisettias tap-tap against the cracked stucco wall. A line of stiff yellowish half-washed clothes jittered on a rusty wire in the side yard.

And no one did it better than Ross Macdonald:

The city of Santa Teresa is built on a slope which begins at the edge of the sea and rises more and more steeply toward the coastal mountains in a series of ascending ridges. Padre Ridge is the first and lowest of these, and the only one inside the city limits.

It was fairly expensive territory, an established neighborhood of well-maintained older houses, many of them with brilliant hanging gardens. The grounds of 1427 were the only ones in the block that looked unkempt. The privet hedge needed clipping. Crabgrass was running rampant in the steep lawn.

Even the house, pink stucco under red tile, had a disused air about it. The drapes were drawn across the front windows. The only sign of life was a house wren which contested my approach to the veranda.

— Ross Macdonald, Black Money

In each of the passages excerpted above the author has used a description of the setting as a tip-off to the reader as to what manner of characters would inhabit such places. Even hints at what lies ahead for both protagonist and reader.

With Hammett it's the stink of the corruption that always follows on the heels of a rich mineral strike. With Chandler, it's a life worn-out by too much living. And with Macdonald, it's a world and its inhabitants as out of sorts as those hedges that need clipping.

Brilliant thumbnail sketches each. If you haven't read them, you owe it to yourself to do so. And each of them was giving the reader a glimpse of a world they had experienced first-hand, if not a contemporary view, then at least one they could dredge up and flesh out from memory.

With the stuff I write it's not that simple.

In his kind note introducing me to the readers of this blog, our man Lopresti mentioned that when it comes to fiction, my particular bailiwick is historical mystery. In my time mining this particular vein of fiction I've experienced first-hand the challenge of delivering to readers strong settings for stories set in a past well before my time.

How to accomplish this?

It's tricky. Here's what I do.

I try to combine exhaustive research with my own experiences and leaven it all with a hefty dose of the writer's greatest tool: imagination.

"Counting Coup," the first historical mystery story I ever wrote, is about a group of people trapped in a remote southwest Montana railway station by hostile Cheyenne warriors during the Cheyenne Uprising of 1873. I used the three-part formula laid out above.

While pursuing my Master's in history, I'd done a ton of research on the western railroads, their expansion, and its impact on Native American tribes in the region, including the Cheyenne.

I've visited southwestern Montana many times, and the country is largely unchanged, so I had a good visual image to work from.

Imagination!

An example of the end result:

Wash and Chance made it over the rise and and into the valley of the Gallatin just ahead of that storm. It had taken three days of hard riding to get to the railhead, and the horses were all but played out.

The entire last day finished setting their nerves on edge. What with the smoke signals and the tracks of all the unshod ponies they'd seen, there was enough sign to make a body think he was riding right through the heart of the Cheyenne Nation.

Stretching away to north and south below them lay the broad flood plain of the Gallatin. The river itself meandered along the valley floor, with the more slender, silver ribbon of rail line mirroring it, running off forever in either direction. The reds of the tamarack and the golds of the aspen and the greens of the fir created a burst of color on the hills that flanked the river on either side, their hues all the more vivid when set against the white of the previous evening's uncharacteristically early snowfall.

"Suicide Blonde," another of my historical mystery stories, is set in 1962 Las Vegas. Again, the formula.

I did plenty of research on Vegas up to and including this time when Sinatra and his buddies strutted around like they owned the place.

I lived and worked in Vegas for a couple of years and have been back a few times since. I am here to tell you, Vegas is one of those places that, as much as it changes, doesn't really change.

Imagination!

Which gets you:

Because the Hoover boys had started tapping phones left and right since the big fuss at Apalachin a few years back, Howard and I had a system we used when we needed to see each other outside of the normal routine. If one of us suggested we meet at the Four Queens, we met at Caesar's. If the California, then we'd go to the Aladdin, and so on. We also agreed to double our elapsed time till we met, so when I said twenty minutes, that meant I'd be there in ten. We figured he had a permanent tail anyway, but it was fun messing with the feds, regardless.

The Strip flashed and winked and beckoned to me off in the distance down Desert Inn as I drove to Caesar's. It never ceases to amaze me what a difference the combination of black desert night, millions of lights, and all that wattage from Hoover Dam made, because Las Vegas looked so small and ugly and shabby in the day time. She used the night and all those bright lights like an over-age working girl uses a dimply lit cocktail lounge and a heavy coat of makeup to ply her trade.

Howard liked Caesar's. We didn't do any of the regular business there, and Howard liked that, too. Most of all, Howard liked the way the place was always hopping in the months since Sinatra took that angry walk across the street from the Sands and offered to move his act to Caesar's. Howard didn't really care to run elbows with the Chairman and his pack, he just liked talking in places where the type of noise generated by their mere presence could cover our conversations.

You may have noticed that in both examples used above I've interspersed description of the setting with action, historical references and plot points. That's partly stylistic and partly a necessity. I rarely find straight description engaging when I'm reading fiction (in the hands of a master such as Hemingway, Chandler or Macdonald that's another story, but they tend to be the exception), so I try to seamlessly integrate it into the narrative. Also, since I'm attempting to evoke a setting that is lost to the modern reader in anything but received images, I try to get into a few well-placed historical references that help establish the setting as, say, not just Las Vegas, but early 1960s Las Vegas. Doing so in this manner can save a writer of historical mysteries a whole lot of trying to tease out these sorts of details in dialogue (and boy, can that sort of exposition come across as clunky if not handled exactly right!).

So there you have it: an extended rumination on the importance of one of the most overlooked and powerful tools in your writer's toolbox: setting. The stronger you build it, the more your readers will thank you for it, regardless of genre, regardless of time period.

Because setting is both ubiquitous and timeless. Easy to overdo and certainly easy to get wrong. But when you get it right, your story is all the stronger for it!

24 May 2023

Moms Get Mad (and Get Lawyers)

Back in February, I wrote a piece about publishers cleaning up writers who’d fallen out of fashion, or more to the point, whose work would sound offensive to the contemporary ear – specific examples being Roald Dahl, Ian Fleming, and Agatha Christie. This is a practice commonly known as bowdlerization, after Dr. Thomas Bowdler, who published a 19th-century edition of Shakespeare with the naughty bits eliminated. Aside from the insult to the authors, my chief complaint is that it irons out context.

Mencken once remarked that a Puritan is someone who’s afraid that somebody, somewhere, is having fun.

The latest iteration of book-banning has dragged in Satan worship and the predatory sexual grooming of children, so plainly, calmer heads haven’t prevailed. It’s belaboring the obvious to say that the fight against Woke is consciously a fight to marginalize the ‘other,’ and personally, I think the rest of us would be better off if these mouth-breathers were out of the gene pool, but far be it from me.

Which brings us to Ron DeSantis.

DeSantis is fighting above his weight class, going after the Mouse. Disney is going to wipe the canvas with him. And instead of being a savvy, calculating political animal, triangulating his every advantage, he’s advertising himself as a vindictive little shit, who simply isn’t ready for prime time. Are we meant to take any of it seriously?Here’s the next wrinkle.

A group ofBertelsmann has a dog in this fight. The way to wrap your head around it is to realize the big money isn’t in James Paterson or Diana Gabaldon, no disrespect. The big money’s in textbooks. And a state like

The most interesting thing about this new lawsuit is that it doesn’t challenge

See you in court.

23 May 2023

In Search of the New Normal

|

| Stacy Woodson, Michael, and David Dean at the Ellery Queen’s Readers Award presentation. (Photo by Ché Ryback) |

During the past seventeen-plus years, I developed a less-than-optimal schedule for writing and editing.

Each morning Monday, Wednesday, and Friday; all-day Tuesday and Thursday; and occasional evenings and weekends on concert days, I drove downtown to my part-time job as marketing director of a symphony orchestra. I spent afternoons Monday, Wednesday, and Friday editing a bi-monthly gardening magazine and a weekly gardening newsletter. Editing anthologies, Black Cat Mystery Magazine, and Black Cat Weekly, as well as writing short fiction, SleuthSayers posts, and the like was shoehorned into evenings, weekends, and moments stolen from my other commitments.

Until recently, working sixty-plus hours each week was the only way to accomplish all of these things and was “normal.” After leaving the symphony, I need to establish a new normal.

|

| Terry Shames affixing Michael’s name badge before the Edgar Awards banquet. (Photo by Aslam Chalom) |

I spent my first week in New York and Bethesda, attending the Edgar Awards and Malice Domestic. These were highly invigorating, but not part of a “normal” week, and I returned home pumped and ready to dive into my new schedule, whatever it might be.

My commitment to the gardening magazine and the gardening newsletter remains, so I’m still devoting Monday, Wednesday, and Friday afternoons to them. Because I’m already spending these half-days editing, I decided to devote the entirety of M-W-F to editing, and have spent my first few weeks reading submissions to Black Cat Weekly and Mickey Finn: 21st Century Noir, vol. 5, reviewing the publisher’s copyedits to Prohibition Peepers, and developing a rough schedule to ensure I meet my editing commitments.

Tuesdays and Thursdays are devoted to writing. So far, I’ve finished and submitted one story, think I’ve resolved a problem with another story that’s been vexing me for years, have been fussing with a story a co-writer and I have kicked back and forth a few times, and have written this post.

|

| Moderator Deborah Lacy, Michael, Carla Coupe, Linda Landrigan, and Josh Pachter on Short Stories: Magazines & Anthologies panel at Malice Domestic. (Photo by Neil Plakcy) |

Though I’m still doing some writing and editing during evenings and weekends, I’m able to spend more time with Temple, and we’ve been doing a few things we’ve not had time for prior to now, such as making a last-minute decision to attend a Marc Cohn concert and planning an upcoming trip on the Texas State Railroad.

So far, this schedule is working.

Except.

Do you have any idea how many time-consuming errands and how many household tasks one can self-generate to prevent sitting at the computer?

So, how about sharing some tips with me: How do you schedule your writing time? How do you avoid procrastination? And, how do you ensure quality time with your significant other?

I recently appeared on the Central Texas Life with Ann Harder podcast, discussing, among other things, four stories that were nominated for awards last year. It’s available on YouTube and wherever podcasts are available.

I’ll be presenting two sessions at the Between the Pages Writers Conference June 9-11 in Springfield, Missouri: “Editorial Sausage,” a behind-the-scenes look at how short story anthologies and fiction magazines are put together, and “Plot Stories Using a Decision Tree,” how using well-developed decision trees can generate multiple stories. Learn more about the conference and the other speakers here.

22 May 2023

Writing is thinking.

by Chris Knopf

My wife said to me around the time we first met, “Writing is thinking.” That’s an excellent notion, I thought at the time, though I didn’t write it down. I could argue, and I shall for the purpose of this discussion, that much of writing begins with feelings. These are forms of thought without language. They are randomly firing neurons, unclarified emotions, mood swings, inchoate brain scramble, that compel one to make sense of it all if you’re so inclined.

And

if you are, you may sit down and try to turn these inarticulate surges inside

the mind into words on the page. You may

ask yourself, what am I thinking, presuming that those feelings are indeed embryonic

thoughts? But if it goes well, you can begin to stumble

around trying to apply words to these impulses, leading to sentences, then paragraphs,

then pages and chapters, etc.

With luck and effort, something akin to discourse, or fiction, will emerge.

There are theories of quantum mechanics that maintain that the properties of sub-atomic particles only behave in an orderly, predictable way when observed. That the observer enforces a certain type of logic and reason upon the physical world.

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/1998/02/980227055013.htm

Could it be that the act of observing ones feelings brings order to otherwise incoherent urges, which then, upon the application of language, reveal their inner nature?

Beats

me, but it’s nice to think so.

Every

writer reports there are times when the writing seems to be writing itself,

that the person behind the keyboard is merely the delivery system, with no

agency over the outcome. If you believe

that feelings are proto thoughts, then perhaps the act of assembling words into

sentences actually organizes the chaos into coherence. Some believe this process of constructing

intelligible meaning out of the mental agitator inside our minds is what separates

us from animals, even smart ones. (I’m

not so sure, having a terrier who knows the difference between “Want to go for a ride?” and “Go get your toy!”)

Another mystery of composition is when a writer discovers something about their story in the process of the writing. Something they never thought of suddenly appears on the page, and it makes sense, often solving a hitch in the works. My wife once asked me why I was so feverishly writing the end of a book, and I told her, “I want to know how this thing turns out.”

The

number of possible connections between brain cells is so staggeringly immense, it’s

not surprising that revelation can seemingly pop out of the blue. It used to be called divine intervention,

back when divinity played a more active role in our understanding of the

universe.

Today,

brain science would assert that it’s merely the interaction between the

subconscious and conscious mind that allows for this reordering of feelings and

impressions into serviceable language. Not

a very romantic notion, I admit. Divine

intervention, or the spark of spontaneous genius seems much more satisfying,

less clinical, more fun. But I think the

likely result of our churning, surprising mental functions to be exciting enough. To my mind, science is a lot more awe inspiring

than any mythological narrative could ever

be.

I’m a fine woodworker, and much of the process involves beginning with an imagined object.

From there, you try to render it in two-dimensional space, with a drawing (I still use a pencil, architectural scale ruler and graph paper). It’s the first proof-of-concept. If you can’t draw it, you can’t build it. The next step is usually a prototype – a physical, 3D rendering of the drawing. As the process progresses, you move gradually from the abstract to the concrete, something you can hold and measure in actual space and time. If the prototype works, you’re good to go. Next step is bringing the actual thing to fruition.I believe that writing is exactly the same

process. That’s why, to me, a house is a

novel. Kitchen cabinets a book of short

stories. A turned spindle a poem.

By the way, Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle could throw a pretty big wrench in the above assumptions, but that’ll have to wait for another essay.

21 May 2023

The Mound Builders

by Leigh Lundin

Wednesday, Rob wrote about Neolithic graves in Europe. We hear about burial mounds, bogs, and even buried boats, mostly in the British Isles, but we know less about our own prehistoric Native Indian culture that preceded what we consider First Nation.

I grew up a short distance (a brief bicycle ride or a longish walk on little-boy legs) from an Indian mound called Hogback. It’s one of the simpler prehistoric Indiana burial sites, especially compared to the Serpentine Mound many miles east. The region was known as a finder's gold mine of points (arrowheads), spear tips, and birdstones.

The latter was a throwing weapon carved into an elongated form to fit the hand. While most birdstones were simply shaped without regard for museums that might come long after, a few have been found carved into the likeness of a bird with folded wings. An ancient craftsman had taken the time and effort to indulge in aesthetics, an astonishing reach across time and space.

Mounds

Indian mounds dotted the landscape through the Illinois, Indiana, Ohio belt, but also could be found in New England and New York. Some have been bulldozed, flattened for farming, or simply, disgustingly, used for easily obtained road-building material. Fortunately, others remain, some accessible by the public.

A curious question has arisen. Genetic research has shown the four major native American bloodlines descend from migrants traversing the Bering Land Bridge, a fifth strain suggests a prehistoric European migration.† Not only is the DNA distinctive, but napping technology and burial practices differed. Were the mounds from this ancient group?

Classmates, Lela, Diane, and Kristi, found this fascinating documentary.

That Which Remains

One day I mounted an expedition to search the mound (no digging, just scoping the ground) and I made a find. It was a perfect, miniature axe head. I rushed home to show my parents.

|

| brachiopod |

My dad took one glance and said, "Not an axe head." I must have looked stricken because he handed it back and smiled. "It's much, much older. It's a brachiopod."

That was cool. And emblematic of Dad, an encyclopedic Google before Google. How many fathers could instantly identify a brachiopod by name?

Credit

Inspiration and following links are thanks to bright, beautiful, and brainy classmates Diane, Lela, and Kristi. They are an amazing resource.

- DNR: Indiana’s Prehistoric Mounds and Earthworks

- NPR: Prehistoric Treasure In The Fields Of Indiana

- PDF: Paleolithic, Neolithic, Copper, Iron Ages of Indiana

† Distant European ancestry isn’t unique amongst anomalies. Melanesian and Australian genes have unexpectedly popped up indigenous American populations.

20 May 2023

Pay to Play?--A New Look at an Old Question

by John Floyd

Today's column, like many of my SleuthSayers posts lately, was triggered by something I happened to see online--in this case a recent discussion about whether short-fiction writers should send stories to markets that charge submission fees.

So . . . should you or shouldn't you?

The answer's up to you. Personally, I don't like submission fees, and I don't send stories to those places that charge them.

NOTE: We're not talking about fees to submit novel manuscripts, or fees paid to an agent or publisher, or fees for reviews or contest entries. I would say No to all those too, but the topic here is the submission of short stories.

Another question: Is it even legal for a publication (usually a magazine) to charge fees for story submissions? That answer to that is Yes. But why would they do it?

I've heard them give several reasons:

1. To offset operational costs like printing, payroll, website hosting, and other expenses

2. To allow them to pay the writers whose stories are accepted and published.

3. To reduce the competition and, as a result, speed up response times.

4. To serve as a substitute for what writers once paid for postage, paper, envelopes, printing, etc.

(Reasons #3 and #4 remind me of a Richard Gere quote from the movie Breathless (1983). His girlfriend says to him, on the subject of ambition, that she has to think about the future. He replies, "The future? Yeah, I heard about it. Never seen it. Sounds like bullshit to me.")

Another reason for charging submission fees--sometimes called reading fees--could be that the whole operation is a scam. There are certainly some of those out there, but for this discussion let's rule them out and focus on legitimate markets.

Speaking of legitimate markets, it's disappointing to me that so many literary magazines charge submission fees. Yes, I know, many of them are financially-strapped university journals--but some are high-level and highly-respected publications, and most don't even pay the authors whose stories are accepted. I won't say I haven't been tempted to pay them the three dollars or five dollars or whatever it takes to submit a story--but I have resisted that temptation. If by chance I did pay up, and happened to get accepted and published in one of those, I think the fact that I'd paid to have my story considered would make me a little less proud of it. Another way of saying that is, I would have more respect for those respected markets if they chose not to charge a fee to submit.

The really frustrating thing is that many of the stories published in lit journals come from established, well-known writers who do get paid for their stories, while only a small percentage comes from the slush pile of beginning or less-recognizable writers who won't get paid even if they happen to get accepted. Add to that the fact that those struggling writers are probably less able to afford the submission fees that they must pay just to be considered. I can picture a frowning Lt. Columbo turning at the castle door and saying to the king, "One more thing. Just to make sure I understand this: The peasants are funding the party so you guys can drink and dance?" But maybe I'm being too cynical.

Now, having said all that . . . Is there any middle ground, here? Well, I've noticed that some places will waive their fees if you submit early enough in the month, and the fees would kick in only after a certain number of submissions have been received. Others charge no submission fee if you're a subscriber to the publication or if you belong to a related organization, and still others charge varying fees depending on whether you want editorial feedback, etc. But they're still fees.

As I implied in the title of this post, this issue of charging submission fees is nothing new. Whether you pay them or not boils down to how much you believe in the old saying that money should flow to the writer and not the other way around.

Anyhow, that's my update, and certainly my opinion only. What's your take on all this? Do you ever pay submission fees to publications? If not, why not? If you do pay fees, how do you decide when and where? Only pay them to the most respected markets? Only when the fee is low? Only occasionally? Please let me know in the comments section. (Don't worry, there's no charge.)

Whatever your policy is, happy writing, and good luck with every story you send in!

I'll be back in two weeks.

19 May 2023

The tomatoes stink, but you should really try the pie

Back in May 2021, I shared some memories of my mother, and it occurs to me to revisit her story at least once more before this month of mothers passes us by.

Early last year I finished assembling a Word doc containing all the recipes she left behind when she died in 2016. They came in two forms. The first was a giant box of index cards, and frankly, those recipes were largely unremarkable. Like a lot of home cooks, she snipped recipes she discovered in magazines, and gradually altered them to her taste the more she experimented with them. A few of these truly became her own, but most did not.

The second group of recipes were far more interesting. In a “marble” cover composition notebook she kept what can probably best be described as a cooking journal. In this book, she recorded recipes that she had just thrown together off the top of her head, along with occasional diary-like entries and comical asides.

The existence of the journal came as a surprise. I could not imagine her actually taking pencil to paper in this way. She was born in Italy, so English was forever a second language to her. She did not take to writing easily. She never finished high school, and her only jobs in life required manual labor. Hence, her notebook is filled with misspellings and wonky grammar. But I love this little book because I can see her mind at work, trying to make sense of her intuitive cooking process. I’m going to share some entries from the notebook exactly as written. Warning: punctuation is nonexistent, and the prose is somewhat hard to parse:

Tomatos

for jars 2 colander (colapasta) makes 6 1 quart jars 1 buscel makes approx 18 jars. I made on my birthday 8-21-01 the last time I made in 2000 also on my birtday. Sthings because I got gipt*

Where to begin with this? I had not known that the word colander in Italian is colapasta, so that was a revelation as I was editing. The word buscel is her rendering of bushel.

I don’t know why she would throw in the non sequitur about canning tomatoes on her birthday; possibly it served to remind her what time of year she traditionally bought and canned tomatoes. I don’t think she noted the date to remind herself when the produce was at its peak of flavor. The last line—which I translate as stinks because I got gypped**—reflects a theme that crops up often in these pages. She is convinced that a particular farmstand in New Jersey sells subpar tomatoes. Here’s another dig:

August 29

The past 4-5 days Im making tomato there are very bad I got them from the farm never again

This is the Last Time

I love how she capitalizes those last two words.

In a few entries we find her making handmade egg noodles, which she generously plans to mail to a former neighbor who retired to Indiana. I can’t recall the last time I received a box of handmade noodles in the mail, let alone handmade anything, but I do recall that this neighbor loved the chicken soup my mom served with these noodles.

Shortly after embarking on this editing project, I realized that the recipes in this book were largely unusable as written. They are more lab notes than recipes. She’s trying to figure out which ratios of ingredients have the greatest impact on the final dish, and that’s too backstage to interest most of us. If I ever hoped to share her discoveries with family members, I’d need to test each recipe by making each dish myself. I also saw that in some cases I’d need to offer footnotes to explain to the uninitiated what Mom was talking about.

also on Sep. 7Translation: In a magazine called La Cucina Italiana, she spotted an article on a regional diamond-shaped pasta dish which she chose to call Tacconelle Molise. (Modern foodies generally describe the pasta as typical of the Abruzzo region. Years after my mother left Italy, “the Abruzzi” she knew as a child split politically into two distinct regions—Abruzzo and Molise.) Mom hailed from a village in Molise called Cantalupo. Clearly, the recipe inspired her recollection of that dish, and the urge to make it.

I made Tacconelle Molise dis is homemade pasta in shepe of diamanti. Because I seen it in La Cucina Italiana in Cantalupo we made this all the time with fresh tomato sauce

All professional writers have had the experience of reading a sentence, detecting that a critical word is missing, yet still being able to comprehend the sentence anyway. But I have no clue how to read the second-to-last sentence in this recipe:

Sep. 5 — 01

I made a pie today with 5 nactarine & 2 plums 1/4 sugar 1/4 tapioca 1 tb. of lemon juice cinamon & nutmeg I can bake and tell if it is good pie is OK.

To bad nobody is here to eat it.

Not sure what kind of pie this is. It doesn’t sound like a two-crust pie, but maybe more of a hand pie, tart, or galette. The penultimate line remains as cryptic to me as it was the first time I read it. Is she saying she baked the pie, and tasted it solely to determine its quality? Or is another reading possible?

The last line, on the other hand, is abundantly clear, and touches on another of her favorite themes. She made a pie that can only be eaten by herself and her husband, because her three ungrateful sons have left the nest empty.

Which brings me, I guess, to the only advice I can offer you this May. If your mother is still with you, by all means visit sometime and gorge yourself silly on pasta and pie.

A belated happy Mother’s Day to all.

* * *

Notes: