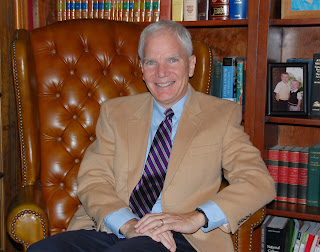

Over the past several weeks it's been my pleasure to participate in several Zoom sessions with other writers and writers' groups. I always learn something from these events, and one thing I've come to expect are lots of questions and comments about markets for short stories--and specifically short mystery stories. All of us seem to like talking (and hearing) about places we might be able to sell what we write.

So, as I was stewing over what to post today, I decided it might be helpful (at least to me, who needed to come up with something so I don't get thrown out of the SleuthSayers tent) to make some observations about current crime-fiction magazines.

Here are ten of them, in no particular order.

NOTE: All these are paying markets and all have, at one time or another, published my stories.

1. Alfred Hitchcock's Mystery Magazine -- Editor: Linda Landrigan. Established 1955. AHMM takes submissions year-round via their own online submission system, pays on acceptance, publishes six issues a year, and provides three author copies on or before the publication date. Once submitted, your story can be tracked anytime by accessing their system--it shows a list of all your submissions by date, along with status (open/closed) and category (received/accepted/rejected). Response times seem to run from 12 to 14 months, whether a story is accepted or rejected (probably because Linda has often said she personally reads every story submitted), and there's also a long wait time between acceptance and publication. As for preferences, AH will consider any story that includes a crime as a part of its plot, and they have been receptive to cross-genre stories like westerns, humor, paranormal/fantasy, etc.--I had a western there this past fall and I have a science-fiction story coming up soon. Multiple submissions are allowed, but most authors agree that you should space them out a bit--and I also try not to overload the system by having too many stories (more than, say, four or five) awaiting a decision at any one time. They require previously unpublished stories of up to 12,000 words, and have occasionally published flash mysteries of under 1000. Payment is between 5 and 8 cents a word. The longest of my AHMM stories, if it matters, was about 13,000 words and the shortest was 1200 (the first story I sold them, back in 1995).

2. Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine -- Editor: Janet Hutchings. Established 1941. EQMM and AHMM are sister publications and are a part of Dell Magazines, but they do not read each other's submissions. In other words, you should feel free to send AHMM a story that EQMM has rejected, and vice versa. Like AH, EQ publishes only original stories (no reprints), they publish six issues a year, they accept submissions year-rouind, and they use a similar online submission system. They also pay on acceptance and send the author three complimentary copies of issues in which their stories appear. An interesting thing about EQMM is that they have a Department of First Stories geared to those writers who have not yet published a short story (this is a great advantage to those who qualify). I've found that response times for rejections seem to run anywhere from several weeks to three months, and acceptances from three to five months. The longer they keep a story without a response--at least in my experience--the better the result. Time between acceptance and publication can, again, be a long while; they currently have one story of mine that was submitted in October 2021 and accepted in February 2022. Preferences: Janet seems less likely than Linda to take westerns or stories with otherworldly elements (though they've occasionally done so), and EQMM seems to especially like stories that are notably unique or different in some way--but once again, any story that includes a crime is considered a mystery and is fair game. Multiple submissions are fine, and I try to follow the same rules at EQ as I do at AH: space out the submissions and try not to pack the queue with too many stories that have not yet received a response. They will consider stories up to 12,000 words in length, though their preferred range is 2500 to 8000, and they occasionally publish flash mysteries. Like AHMM, their pay is between 5 and 8 cents a word. My longest EQMM story was 7500 words and the shortest was 3600--and I've also sold them two "mystery poems." NOTE: EQ doesn't say anything specifically about simultaneous submissions (AH does; it allows them), but I still don't do it, for either of the Dell magazines. When I send a story to AH or EQ, I don't send that story anyplace else until I've gotten a response first. My opinion only.

3. The Strand Magazine -- Editor: Andrew F. Gulli. Established 1999 in Birmingham, Michigan, as a rebirth of the old Strand Magazine in London. They prefer stories between 2000 and 6000 words and have no set submission period, and require previously unpublished stories. Their policy is to not respond to a submission unless it's an acceptance, but acceptances--when they do happen--come fairly quickly and accepted stories usually appear in the very next issue, so there's not much wait time before publication. They publish three or four issues a year and four or five stories in each issue. Payment amounts vary. Of the stories I've sold to the Strand, the longest was 10,000 and the shortest 2500, and I average around 5000, which is (as stated earlier) in their target range. Other preferences: The editor has said he likes stories with plot twists, and they usually avoid stories with paranormal elements. One submission tip: Be sure to include a phone number in the contact info on the first page of your manuscript--Andrew has on several occasions notified me of an acceptance via a phone call, and not only recently; he called me in response to my very first submission to the Strand in 1999. Most of my submissions there have been straight crime stories, one of which was a private eye story.

4. Black Cat Mystery Magazine -- Editor: Michael Bracken. Established 2017. BCMM does not receive submissions year-round, only in announced submission periods. Their site says they publish two to four issues a year. There's no set response time, but I've found they usually reply in a few months--no overly long waits. They require previously unpublished stories. Preferences: Michael has a number of style and formatting restrictions you need to know about in the guidelines, available at the website. Also, submitted stories should have no otherworldly content. If there are what appear to be paranormal elements in the plot, those should be resolved and shown to be real-world before the end of the story (those Bigfoot tracks were really the work of Billy Ray Gooberbrain, playing tricks on his brother). Most of my stories there have been undiluted crime-suspense stories (one was a PI story), though two were cross-genre westerns that were accepted before Michael became the head fred.

5. Mystery Magazine (previously Mystery Weekly) -- Editor: Kerry Carter. Established 2015, based in Ontario, Canada. Word length at Mystery Magazine is 1000 to 7500 for regular stories and less than 1000 for what they call "You Solve It" mysteries that ask the reader to come up with the solution. They pay 2 cents a word, on acceptance, for most short stories and a flat rate for the You-Solve-Its. Payments are made via PayPal, though mine have all been (at my request) in the form of an Amazon gift card. Preferences: MM is said to be especially receptive to stories with humor and stories with unique settings (both place and time), and apparently they avoid stories that "date" themselves or use excessive violence or cruelty to animals. They've also said they prefer cross-genre stories and that they never receive enough stories with horror, fantasy, or SF elements. In case it matters, most of my stories at MM have been regular crime fiction, but one was a funny mystery, five included supernatural elements, and four were westerns. Submissions are made via their website, and you can access a countdown screen that shows how many stores are ahead of yours in the submission queue--though some stories occasionally jump the line and get accepted before their time. I've found that a wait of around a month is usually a good estimate. My longest story at MM so far was 6900 words and the shortest was 1000.

6. Sherlock Holmes Mystery Magazine -- Editor: Carla Coupe. Established 2008. This is a sister publication to Black Cat Mystery Magazine, and both of them are products of Wildside Press. My first sale to SHMM was in 2012, and I remember that I found the guidelines at a site called Better Holmes and Gardens. (Seriously.) I think SHMM began as a quarterly, and for a long time publication of the magazine was irregular, sometimes with many months between issues--but lately that has leveled out; I had a mystery in their most recent issue last month, and I signed a contract this past week for another one in their next issue. Most of my stories there have been fairly short mysteries, and usually lighthearted. The longest was 4800 words, the shortest 900.

7. Tough -- Publisher: Rusty Barnes. Established 2017, online-only publication. Tough is said to be both a "crime fiction journal" and a "blogazine of crime stories." Preference: stories with rural settings. They require original stories and occasional reprints--but the reprints are considered on a case-by-case basis and cannot have been available anywhere online. Their pay is a flat rate of $50 for original stories and $25 for reprints. There are some strict formatting guidelines, available at their website. Submissions are done at their site, via Submittable, and your story can be tracked by logging in to Submittable for status reports. I've published only one story at Tough, and it was a 6000-word original mystery/crime story set in the South's deepest backwoods.

8. Mystery Tribune -- Editor: Ehsan Ehsani. Requires previously unpublished stories, accepts fiction submissions year-round, and publishes four times a year. According to their site, most fiction submissions for the print editions are between 3000 and 6000, and all should be less than 10,000 words. Flash fiction is generally published in their online editions. They say they'll respond to submissions within three months, though it's sometimes longer, and they have a submissions system that allows writers to check the status (received/in progress, etc.) online. Time between acceptance and publication can be many months, and in my case--I've sold them only one story, a 3000-word twisty mystery--I wasn't notified when it was published and have never gotten a copy of the issue. But I was paid, and from everything I've heard and seen, the magazine is a quality publication. It certainly features many well-known authors in its back issues. As for pay, that varies, and I understand there's no payment at all for flash fiction.

9. Black Cat Weekly -- Editor/publisher: John Betancourt. Associate editors: Barb Goffman and Michael Bracken. This market, from Wildside Press, is a bit different in that it's invitation-only. The magazine began in 2020 as Black Cat Mystery and SF E-Book Club, and Black Cat Weekly started in 2021. It's digital-only (no print editions), new issues are released every Sunday, and both Barb and Michael name one story as personal "picks" for their issues. The pay rate ranges from $25 to $100, depending on story length. The magazine features reprints of stories chosen by the editors and occasionally features new stories as well. (Barb told me she mostly does reprints and Michael mostly buys rights to new stories.) My longest story at Black Cat Weekly was an original story of 7600 words and my shortest was a reprint of 2300.

10. Woman's World -- Editor: Alessandra Pollock. Established 1981, circulation 1.6 million. They publish one mystery story and one romance story in every weekly issue. Wordcount is 700 max for mysteries and 800 for romances. All my sales there have been mystery stories except for two romances, years ago. In case you're interested, when I first started sending stories to WW their mysteries were 1000 words max and paid $500 each their romances were 1500 words max and paid $1000 each. Their mysteries were once (like the romances) traditionally-told stories, but the mysteries changed in 2004 to an interactive format which features a separate "solution box" such that readers are invited to solve the mysteries themselves. Preferences seem to be lighthearted crime stories that include no explicit sex or violence, no strong language, and no controversial subjects such as religion, politics, etc. They also seem to prefer female protagonists, local settings vs. foreign, easygoing vs. gritty, good-guy-wins vs. bad-guy-wins, etc., but I have happily broken those rules and made sales, so make of that what you will. Also, be aware that I've often heard that WW stories must have three suspects in each mystery--that is simply not true. Also false is the rumor that you must be a female writer to do well at this market. You don't. Just write a good mystery that gives the reader enough information to solve the puzzle on his/her own, don't go over 700 words, don't put a pet in jeopardy, and send 'em the story. A tip that might help: they seem to like series stories that feature the same characters each time--that's something that works out well for both the magazine and the writer.

One market I didn't include in the above list is The Saturday Evening Post -- Established 1821, circulation (in 2018) 240,000. A word of explanation: I've had ten stories published there, five of them mysteries, BUT . . . my stories appeared in the print edition of the SEP (they publish one piece of fiction in every issue, which is once every two months); those stories were sold via my agent and I've had no direct contact with the editor, Patrick Perry. The point I'm building up to, here, is that there is also an online version of The Saturday Evening Post, and several of my writers friends have had good success with mystery stories there. I've not tried submitting anything to the online Post so I don't know any of the specifics (pay, frequency, masthead, response time, needs, preferences, etc.)--but it appears to be a viable market for crime/mystery fiction.

Again, these are paying markets, but there are also non-paying publications that might be worthy of your work and time--you'll have to decide that for yourself. I have occasionally submitted my own stories, sometimes original stories and sometimes reprints, to those if I like the publication and if I like the editor. Two that come immediately to mind are Mysterical-E (editor Joseph DeMarco) and Kings River Life (editor Lorie Lewis Ham). They are respected markets, they're online-only, they feature mystery stories, and both Joe and Lorie have been kind to me over the years.

By the way . . . I heard someone say recently that most awards and best-of selections are going not to magazine stories but to stories in anthologies. I agree to some extent, but I must mention--without boring you with details--that I and others have had good luck in that regard with stories in the magazines listed above. Yes, awards and best-of judges and editors do look at mystery anthologies when they're choosing stories, as they should--but I assure you they also look at magazines.

Please let me know, in the comments section below, what you think about all this. Which markets have been the best homes for your stories? Which do you subscribe to, and/or read regularly? Do you have any corrections or updates to the information I've provided above? (I assure you they are welcome.) Did I leave anything out? How about your own experiences with these markets, or with others I failed to include? Do you write anything other than mysteries? Have you found you're submitting more often to anthologies that to magazines?

Now, back to writing.

Wonder where I should send the story I'm working on now . . .

.jpg)