What makes a crime story? A crime, sure, but that can infer a creative box, as if the crime might ultimately confine the story. Not so. A crime story can do anything, given the ambition.

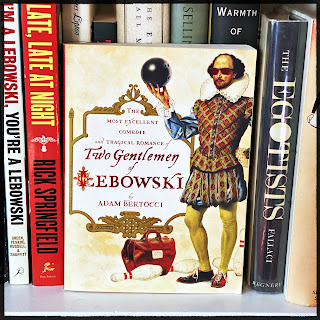

Consider The Big Lebowski (1998), released 25 years ago this month. Even if you've never seen the oddball classic, you know the main character: The Dude (Jeff Bridges). And if the movie confounded you, you're not alone. Nobody confounds like the Coen brothers.

DOWN THOSE MEAN LANES

Actually, nobody else could've made The Big Lebowski. No Hollywood newbie could've sold a script this indulgent in directorial conceits and character asides. By 1998, though notches on the Coens' belt included Raising Arizona, Miller's Crossing, and the Oscar-winning Fargo.

The Big Lebowski comes disguised as subverted L.A. noir. That's not clear in the opening scenes, with the Dude sniffing milk and the voiceover narration. But resketch Acts One and Two to include the off-camera action, and themes will sound familiar:

- Jeffrey "Big" Lebowksi is a philanthropist statesman of the L.A. Chamber of Commerce set. In reality, he married well and stinks at business. His daughter, Maude (Julianne Moore), controls the wealth through a family trust. Big's trophy wife, Bunny, is causing him epic grief by sleeping around and piling up gambling debts to pornographer Jackie Treehorn.

- Treehorn sends goons to collect from Big, but the goons mistakenly barge in on unemployed stoner Jeffrey "The Dude" Lebowski. A rug is soiled.

- Bunny disappears.

- Uli, an ex-Europop nihilist and Bunny's co-star in a Treehorn low-budget production, senses opportunity. Uli and his crew send Big a ransom note for $1,000,000, despite having no idea where Bunny actually went.

- Big senses a similar opportunity. Bunny has disappeared before, after all. She might be playing him for another payout. Big finagles a $1,000,000 withdrawal from the Lebowski trust to fund the ransom--which he pockets instead. He prepares a drop bag loaded with old papers.

- Big needs a fall guy for cash sure to be missed. Stealing a replacement rug from his mansion is the perfect mark: The Dude. Suspicion of double-cross and kidnapper retribution would fall squarely on the wayward but pliable Dude. Sure enough, the Dude is guilt-tripped into making a ransom drop he believes is real.

- The drop goes disastrously, thanks to the Dude's bowling pal, Walter (John Goodman). The Dude is left thinking he has someone else's million, no explanation, and the sudden need to find Bunny.

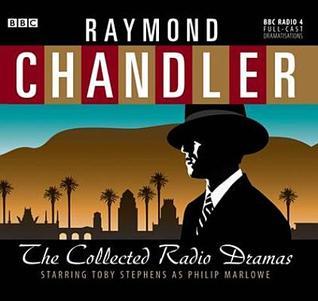

Corruption, extortion, vice, adultery, mystery, questions of personal honor. It's a Marlowe riff, though you can almost hear Chandler grouse over the liberties taken.

Marlowe was in the trouble business. The Dude isn't in any business, let alone walking mean streets. His 60s-era sense of justice has devolved to jaded memories and bathtub tokes to whale cries on his headphones. He's forced to turn detective when what he thinks is the loot gets stolen along with his car. His looking for his ride or Bunny or both is a laid-back search, with ample time for bowling. Clues stumble over him from over-the-top characters who'd be at home in any Marlowe story. The Dude gets threatened, followed, drugged, lured to bed, and beat up by the Malibu cops--if any of that sounds familiar.

Subversion or not, The Big Lebowski wears its crime story clothes with clean lines. The confounding parts come with the added layers, and they're ambitious.

SOCIAL CONTEXT

Big is the Korean vet become titan of industry. The Dude and Walter are yin and yang of the Vietnapm years. The backdrop is Iraqi War America. Three wars mark the eternal cycles of time in thinly-veiled allegory. The elder, conservative elite– Big, for example– are empty suits engaged in a money grab. Wars get arranged to protect their interests, and the liberals among the younger set, say like a hippie burnout, get blamed for war's downstream social issues. Attempts to break the cycle can't work unless someone deals with the systemic greed. Probably, no one will.

Take Big's daughter. In a prior age, Maude would've femme fatale-d across the screen. These days, she is too liberated and too busy as an artistic whirlwind. She is by some margin the smartest character in the film, even seeing through Big's shenanigans. Not that she cares much. She's after securing the balance of power for the future generation. She takes more care to retrieve the family rug than to address her dad's fraud.

A STRANGER FROM THE WEST

Scene One opens with a dadgum tumblin' tumbleweed and a Sons of Pioneers tune and The Stranger (Sam Elliott) in full drawl voiceover. The Stranger rambles on how he's seen some things but this tale here might top them all, this tale how the Dude would become the man for his times. Weird, but not accidental. A man rising up right wrongs is a western trope.

As for the Stranger, maybe he's a keeper of time. Maybe he's God. He appears bodily twice, both at the Star Lanes bar, both after the Dude approaches. The first is mid-film, and over a sarsaparilla the Stranger imparts a meaningful cipher: sometimes you eat the bear, and sometimes the bear eats you. The second manifestation is at the end, where the Stranger laments the movie's sole death.

Star Lanes is no average bowling alley. Outside it, wars and aggression rage. L.A. crime laps right to the alley's door. The Dude's car is stolen in their lot. Inside Star Lanes, time passes differently. The fluorescent lights hum, the bowlers can live their best lives, and the pins get racked again and again by mechanical magic. Star Lanes isn't heaven, but it's a higher plane.

AT LEAST IT'S AN ETHOS

Or if Star Lanes is a Garden of Eden, Walter is the serpent. Everyone else is trying to relax over a few frames, but Walter steps all over the mood with his thirst to impose his personal code on league and non-league play. A practice game infraction escalates immediately to Walter's gunpoint demand the roll gets marked zero.

Walter represents order. More precisely, the folly of seeking order. Walter insists on his solution for everything, except his problem-solving instincts are disastrous. He turns Big's fake drop into chaos by substituting a second fake bag stuffed with underwear. Walter screws up the Dude's attempts to recover his car. Walter's real problem is understanding this universe. Cosmic and random forces work vastly outside human control. We mortals just need to roll with it. The Dude would, if Walter let him.

LET US ABIDE

For The Big Lebowski's first hour or so, we're fed outrageous characters and Marlowe-ish flourishes. It's a set-up. Likely as not, you hadn't the pivotal guy in plain sight: the Dude's and Walter's third wheel, Donny (Steve Buscemi).

Donny is a happy, in-the-moment guy. He just wants to bowl. He can't ever understand what the Dude and Walter are wrangling over. Missing money? Kidnapped porn queen? Rugs that pull a room together? It's all over Donny's head. The one time he cares enough to ride along on the case, it's because the trip goes by the North Hollywood In-N-Out Burger.

Not long after, the ransom plot has fallen apart. The Dude confronts Big j'accuse-style about the switcheroo scam, and Bunny returns from partying in Palm Springs. It's wrapped up--and it's been about nothing. The Dude is back where he started. Worse, even. No compensation for the rug or his trashed car.

It's wrapped but not over. No one yet has gotten the bear or been gotten. That happens when Uli and his nihilist buddies confront the Dude, Walter and Donny outside Star Lanes. A hilariously weird scuffle follows. In the aftermath, poor Donny, who never wanted anything but to roll with his buds, keels over from a shock heart attack.

Donny passes young and pointlessly. In the funeral home, while the Dude and Walter haggle over cremains urn pricing, the Coens make plain what this crime caper has been about. The funeral home wall displays a verse from the King James Bible:

Banter, eccentric character turns, absurd scenes, a kidnap that wasn't a kidnap, ransom money never at risk. These things are as flowers in the field. The film says nothing much really changes in the grand play of the cosmos. We live in a disorderly universe, we deal with events of the day, and we die. Unlike true noir, though, the Coens offer hope. The now matters. The now is all we'll ever have.

The story ambition hasn't been about crime or death, which quite literally hits the Dude in the face. The Big Lebowski is about finding harmony in life. After his hippie years and jaded downslide, he can release that baggage and just go bowling. In the closing scene, the Stranger tells the Dude to take it easy, and only then the Dude gives his pop culture line, delivered in shadow: "The Dude abides." Finally, he can.

.jpg)