Still getting the occasional email criticizing me about my December 16, 2022, article in "Hair Styles" article in SleuthSayers, so I thought I'd give equal time to some pretty cool hairstyles of movie stars from the era.

27 January 2023

Good Hair Styles

26 January 2023

How the Law Really Works

by Eve Fisher

I'm getting pretty tired of memes and op-eds that are shocked, shocked, shocked! about searches and arrests and even convictions, so I thought I'd discuss how things happen in the real world of criminal justice. And I'm going to use plain, simple language, because there too many people running around who have bought a whole lot of legal BS.

(2) If you try to sell illegal drugs, and the cops bust you, you're still guilty even if what you brought to sell was actually lawn clippings in a baggie.

(3) If you try to hire a 13 year old for sex, even if "she" turns out to be a 46 year old portly male detective, you are still guilty of trying to buy a minor for sex.

(4) If you try to sell a 13 year old for sex, even if you have no 13 year old in the stable, and were just trying to scam the purchaser, you are still guilty of pimping, as well as scamming.

(5) If you offer to kill someone for hire, and then pocket the money but don't do it, you're still going to be charged with conspiracy to commit murder.

(6) If you're conspiring with people to kidnap / murder someone or some group of people (such as the ones who conspired to kidnap and execute Michigan Governor Whitmer, or the group in Kansas (HERE) that was going to blow up a Somali community), and an informer has infiltrated your group, and the FBI (or other law enforcement) arrest you before you actually commit the crime - well, there's a reason conspiracy is a crime, and you're gonna find out the hard way.

Basically, it doesn't matter if you didn't get or didn't give what was offered - what matters is that you intended to get or give what was offered.

Cathy the Catburglar comes to Paul's Pawnshop in New York City with a diamond ring valued at $10,000. "Wow, that's a beautiful ring," Paul says to Cathy. "Where'd you get it?"

"Duh. I stole it. I'm a cat burglar. It's right in my name."

"Right," says Paul. "But where did you steal it from?"

"I'd rather not say," Cathy replies, "but don't worry. I didn't steal it around here. Let's just say that an heiress in California will find that her hand feels a little lighter than it used to."

"Gotcha," Paul replies. "I'll give you six grand for the ring." They haggle and eventually settle on a price of $7500.

Paul has committed a federal crime of receiving goods valued at over $5,000 that he knows to be stolen and that crossed state lines. He has also committed third-degree possession of stolen property under New York law. The fact that Paul didn't steal the ring himself or play a role in Cathy's crime does not shield Paul in any way. (DORF)

Another one is the "hearsay doesn't count" defense:

(1) Pretty much every single Mafia and other crime boss who's been indicted, tried, and convicted has been put there by the witness of other criminals - usually their [former] employees. Except for those who got caught cheating on their taxes. Sometimes them, too.

"People commit murders largely in the heat of passion, under the influence of alcohol or drugs, or because they are mentally ill, giving little or no thought to the possible consequences of their acts. The few murderers who plan their crimes beforehand -- for example, professional executioners -- intend and expect to avoid punishment altogether by not getting caught. Some self-destructive individuals may even hope they will be caught and executed." (ACLU)

Or, as someone said recently on Facebook in one of the greatest memes I've ever seen, which said simply, "We already know what caused the shootings: Hate/Fear/Rage"

But executions are always a popular idea. A commenter on Facebook wrote me that the best way to stop crime and lower prison populations is to execute all violent criminals and drug dealers and - well, it was a long list. I instantly thought of Larry Niven's short story, "The Jigsaw Man" (in the original Dangerous Visions anthology that I've referred to a few times).

Synopsis from Wikipedia, "In the future, criminals convicted of capital offenses are forced to donate all of their organs to medicine, so that their body parts can be used to save lives and thus repay society for their crimes. However, high demand for organs has inspired lawmakers to lower the bar for execution further and further over time.

The protagonist of the story, certain that he will be convicted of a capital crime, but feeling that the punishment is unfair, escapes from prison and decides to do something really worth dying for. He vandalizes the organ harvesting facility, destroying a large amount of equipment and harvested organs, but when he is recaptured and brought to trial, this crime does not even appear on the charge sheet, as the prosecution is already confident of securing a conviction on his original offense: repeated traffic violations."

So be careful what you advocate for. I've seen how you drive.

25 January 2023

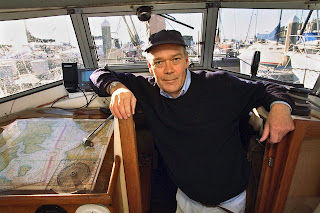

Jonathan Raban

Jonathan

Raban died last week. He was eighty –

not a bad run. He didn’t hit my radar

until Old Glory, but certainly other

people knew who he was already. He

resisted being called a travel writer; like Bruce Chatwin, he was somewhat sui generis, a writer of moods, and

weather, sudden storms and inner barometrics.

He wasn’t always the easiest guy to get along with, it’s said, but he

gave as good as he got.

Old Glory is

about a boat trip down the

This

bemused self-deprecation is of course a fiction, or a convenience, it wears out

its welcome – it’s maybe a Brit thing, too, that affectation – and Raban

discards it, later on. By the time of Passage to Juneau, eighteen years on, the

voice is no longer passive, and it’s fairly caustic, a burden of greater

self-awareness.

Somewhere

in the middle, he wrote the novel Foreign

Land and a memoir, Coasting,

which are back-to-back, and hold a mirror up to one another. Both books are about a sailing trip around

the coastline of

He called the lure of the open road (or the open water) a path to “escape, freedom, and solitude.” He seems to have had a less than joyful childhood, and his taking leave of things is a constant, one restless eye always tipped toward the horizon. I wish him, at the end, safe harbor.

24 January 2023

Boys Two Tax

When I was ten years old, my dad brought home a conversion kit for my bicycle. He installed a banana seat and high-rise butterfly handlebars so that I could ride a Sting-Ray, just like the cool kids.

Alas, Dad could change the bike to cool, but the rider remained unreformed.

I was reminded of my bicycle’s conversion in a rather roundabout Proustian moment the other day. Sitting at my desk in the courthouse basement reviewing cases, I was presented with an officer’s affidavit.

He pulled over a pickup on a routine traffic stop. As he approached the vehicle in the bed, he spotted a Cadillac converter.

Having some familiarity with our local crime trends, I knew that the officer had likely spied a stolen catalytic converter. The voice-to-text, called-in report had changed the stolen object. If one says the words out loud and mumbles just a smidge, it is easy to hear how the substitution occurred.

In the moment, however, my imagination ran wild. I envisioned Hyundai Elantras or Chevy Sparks sprouting tailfins and hood ornaments, stretching out before my eyes until they became El Dorados. The Cadillac converter rolling around in the back of this defendant's pickup brought the transformation from an entry-level motor vehicle to a classic American roadster.

That sort of thing happens when you spend too much time alone in the basement.

Cadillac converter is a petite-typo, a small error, easily understood in a world of dictated reports and auto-corrections. January 2023 has provided several examples already. Perhaps the new year brought software upgrades to the local departments, and the bugs are still being worked out. None of these are significant, but each has successfully taken me away, if briefly, from the subject of the offense to consider the alternative reality posed by the language on the page.

Consider where your mind goes with the following actual examples:

“John Smith was arrested leaving the Budget Sweets.”

Envision the Willy Wonka-esque crime implied by the sentence. Readers might quickly fix this one and picture the malefactor sneaking away from the Budget Suites, a low-rent motel just off the freeway. Lots of offenses occur there. But a discount candy store as a crime scene? Maybe Hershey, Pennsylvania, has that problem, but it is unheard of here in Fort Worth.

Or perhaps this example:

“I apprehended John Smith before he was able to flea.”

If true, legal pundits will be forced to consider the definition of the verb, to flea. Can a pest infestation be a weapon? What constitutes a swarm? Fortunately, my colleagues and I were spared all that scholasticism. Smith merely hoped to run away. He was arrested by the police and not by animal control.

If the workload is heavy and I’m blessed with a smidge of discipline, the above auto-corrections rarely slow me down. They are momentary distractions, encouraging flights of imagination in the free moments. Occasionally, however, the auto-corrections indeed prove disruptive.

The other day, for example, Officer Lawful met Smith and Jones regarding a dispute. The police report described Officer Lawful comforting Smith after hearing his statements. I regularly read examples of officers offering succor to distressed individuals, so the emotional support did not seem out of place. Smith’s version of events changed while being comforted, and Officer Lawful subsequently arrested him.

In a world absorbed only through the printed page, the electronic shifting from confronted to comforted changed my perception of who the arrestee would be. Like a bad plot twist, it took me out of the story, and not in a good way.

As I think about my writing for 2023, I hope that exposure to these errors reminds me of some basic lessons. When I'm writing, the words matter. Seeing silly examples of word choice should prompt me to take extra care with my language decisions in the stories I'm trying to create. At least, I hope it does. The more important lesson for me is the reminder to carefully proofread my pages. And then reread them before hitting "send." I regularly see how a garbled or inattentive word changes my reading of a police report.

My apologies to Michael, Barb, and my other editors for the typos and word choices they’ve comforted.

Until next time.

23 January 2023

Dr. Watson Had How Many Wives?

DR. WATSON HAD HOW MANY WIVES?

by Michael Mallory

How many wives did Dr. John H. Watson, of Sherlock Holmes fame, actually have? The fact that so many people even care about this is a trait of those devoted Sherlockians who like to purport that Holmes and Watson were real people, not iconic fictional characters. That is the “grand game” as put forth by today’s Baker Street Irregulars (BSI), an organization of devoted Holmesophiles who pretend that Watson actually participated in and recorded the adventures of his singular friend, and that this Arthur Conan Doyle chap was simply his literary agent.

My personal opinion of this mindset is that it rather disrespects a major Victorian author, but for these purposes, that is neither here nor there (other than the acknowledgement that by humbugging the grand game, I will never be invited to join the BSI). My purpose is to speak about how many trips the good Dr. Watson made to the altar and why it is even in question.

For nearly 30 years now I have been turning out stories, novels, and even one full-length play featuring Amelia Pettigrew Watson, whom I call “the Second Mrs. Watson.” There is a sound reason for this, to my way of thinking, but many Sherlockians disagree. I have heard theories that Watson was married a total of six times, and once encountered a Sherlockian who claimed to have evidence that the real number of wives was 13! Since this would paint Watson as either the second coming of Bluebeard or the first coming of Mickey Rooney, I did not take him very seriously. For most faithful Sherlockians, however, the number is three, though we only have details of one of them.

Watson’s only indisputably-documented wife was Mary Morstan, the heroine of the novel The Sign of the Four. Mary is mentioned in another half-dozen short stories, and while her union with Watson appeared to be very happy, it was short; she died “off-stage” during Holmes’s “Great Hiatus,” his multi-year disappearance after presumably being killed by Professor Moriarty.

The only other mention of Watson remarrying comes from the story “The Adventure of the Blanched Soldier,” which was published in The Strand Magazine in 1926 and collected in The Case-Book of Sherlock Holmes the next year. In it, Holmes himself writes: “I find from my notebook that it was in January, 1903, just after the conclusion of the Boer War, that I had my visit from Mr. James M. Dodd, a big, fresh, sunburned, upstanding Briton. The good Watson had at that time deserted me for a wife, the only selfish action which I can recall in our association.” One of only two short stories narrated by Holmes himself, “Blanched Soldier” reveals a surprisingly vulnerable detective who, based on the above comment, is hurt and angry over Watson’s abdication for a woman. It also generated one of the biggest mysteries within the Holmesian canon, since this mystery woman was not identified and was never heard from again.

In 1992 I began playing around with the idea of writing a Holmes and Watson pastiche told from a woman’s point of view. Using Irene Adler seemed too obvious, while Mary Watson never seemed to engender such a feeling of replacement in Holmes’s life. Then I remembered the “second,” unknown Mrs. Watson, and from that single reference to her developed Amelia Watson. She is not only Watson’s devoted, slightly younger wife, but I present her as something of a foil to Sherlock, particularly if she believes Holmes is using her husband.

I remain grateful that faithful Sherlockians have enjoyed her adventures, particularly since I have at times treated the legend rather playfully through her POV, the chanciest conceit being that maybe Watson was a better writer than Holmes was an infallible detective, and he fixes his friend’s mistakes in print. The only point of contention I’ve encountered from the faithful is in presenting Amelia as Watson’s second wife instead of the third. But if Mary Morstan was Watson’s second wife, not his first, and Amelia was his third, not his second, who was the first? The answer to that can be found only outside the canon of 56 short stories and four novels written by Arthur Conan Doyle.

Sometime in the late 1940s, author and Sherlockian John Dickson Carr was granted permission to look through Conan Doyle’s private papers in preparation for writing his biography. One thing Carr discovered shocked him. Around 1889, in between the publication of the first Sherlock Holmes adventure A Study in Scarlet (1887) and the second, The Sign of Four (1890), Conan Doyle wrote a three-act play titled Angels of Darkness, which dramatized the American scenes from A Study in Scarlet. Holmes was nowhere to be found in it; instead Watson was the main character. By the play’s end the good doctor was headed toward the altar with a woman named Lucy Ferrier, who was a character from the flashback section of the source novel.

Carr’s dilemma was that this previously unknown work, which Conan Doyle never intended to see the light of day, upended the “facts” of Watson’s life. “Those who have suspected Watson of black perfidy in his relations with women will find their worst suspicions justified,” Carr wrote of his discovery. “Either he had a wife before he married Mary Morstan, or else he heartlessly jilted the poor girl whom he holds in his arms as the curtain falls on Angels in [sic] Darkness.”

Making the problem even murkier for grand gamers, Lucy Ferrier could not be the first Mrs. Watson since The Sign of the Four has her dying in Utah sometime in the 1860s, when Watson would have still been a schoolboy. In light of this stunning discovery, Carr’s felt he had only one option: keep it to himself. He wrote that revealing the woman’s identity would “would upset the whole saga, and pose a problem which the keenest deductive wits of the Baker Street Irregulars could not unravel.” One man, however, accepted the Gordian challenge.

William S. Baring-Gould (1913-1967) was not only the leading Sherlockian of his time; he became something of the St. Paul of Sherlockania, a writer who fashioned the outer-canonical Gospel of Baker Street which is accepted by the faithful to this day. Realizing that John Dickson Carr was right in his assessment that the Watson-Ferrier match would turn the entire saga on its head, he did what all good authors do: he made things up. Baring-Gould put forth the notion that Watson had traveled to San Francisco in the early 1880s and there met a woman whom he subsequently married, but it was not Lucy Ferrier. It was someone named Constance Adams.

Who?

The first mention of Constance Adams appears in Baring-Gould’s 1962 “biography” of Holmes titled Sherlock Holmes of Baker Street, and although she exists nowhere in the writings of Conan Doyle ─ not even in Angels of Darkness ─ having the Baring-Gould imprimatur meant that her existence was taken as a given by many.

Even so, I maintain that Mary was Mrs. Watson #1 and Amelia is #2, and for a very simple reason: in crafting Amelia and John’s adventures, I rely on the Holmesian canon rather than later interpolations by others. The same is true when I write a Holmes pastiche that does not feature Amelia. While I take playful liberties here and there, the guidebook for me begins and ends with those 56 stories and four novels, occasional contradictions and all. (For the record, I also ignore Dorothy L. Sayers’s speculation that the “H” in John H. Watson’s name stood for “Hamish,” which is now acknowledged dogma.) In the Amelia universe, she is the Second Mrs. Watson (though in British editions, she is “the OTHER Mrs. Watson,” which I’ve rather come to like as well).

That said, I have not ignored Constance altogether. In a bow to the non-canonical mythology, I included her in my short story “The Adventure of the Japanese Sword,” which is set in San Francisco, and fully explains her youthful association with Watson which is misinterpreted as matrimonial.

You see, two can play the grand revisionist game.

22 January 2023

Dying Declarations II

by Leigh Lundin

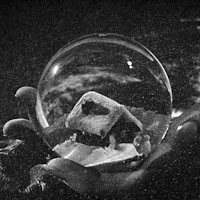

II. A Hiss Before Dying

Lights down, curtain up, the famed film unreels.

Two minutes… ⏱️ … two minutes of reverent silence lapse as the camera passes under a gate bearing an encircled letter K. In the distance, a castle-like mansion beckons, a single lit window draws in the audience.

Through the glass, snow, swirling mysterious snow. When the camera pulls back, the scene reveals a snow globe cupped by an aged, dying man.

As the old man expires, the sphere rolls from his hand and shatters.

At that moment, theatre doors burst open. A piercing shaft of light slices the audience’s peripheral vision. The late-comers stumble and mumble, and their voices boom through the hushed auditorium.

“Hold this. Oh geez, I told that kid extra butter, no ice and lookie, extra ice and no butter. I’m gonna slap him silly. Hey, it’s started already. Oh, it’s that old guy, Orkin something. Scuse me. Oh crap, it’s in black and white.”

“Damn it. I can’t see. Scuse me. Scuse me.”

“Shh! Shh!”

On screen, the dying man whispers something approximating, “Яzzchoz€ßplub.”

“Whuh?”

💬

“What’d he say?”

“Don’t know.”

“Shhh!”

“He said nose rub.”

“Slow snub?”

“Or clothes scrub.”

“No, no. Hose tub.”

“That makes no sense.”

“Maybe he whispered nose blood.”

“Like nosebleed? ’Cause he’s dying?”

“I’m thinkin’ Moe’s Pub.”

“Nonsense, no Moe and no pub.”

“It’s the bar next door. I need a drink.”

“Are you all deaf? He said toe stub.”

“That’s ridiculous.”

“Shhh.”

“Huh?”

“He said snow glub.”

“No way. It was a snow globe, not a glub.”

“When it rolled, it went glub-glub.”

“That’s silly.”

“Honey, would you go back to the concession stand?. I can’t eat popcorn without butter.”

“Shhh!”

“Scuse me. Scuse me. Scuse me.”

“What?”

“Turn off your phone!”

“I’m googling.”

“What’s it say?”

“Yo. Reddit says rosebud.”

“What? That makes even less sense.”

“Facebook misheard it too.”

“Scuse me. Scuse me. Okay, they gave us triple butter.”

“Two hours debate and we still don’t know.”

“I vote to close-caption theatre subtitles.”

“That concessions kid forgot salt.”

“Shhh.”

“#@%£∂!”

👀

“Hey, look. Something’s painted on… on… on that burning thing. What is that?”

“A bedstead?”

“A bobsled?”

“Bob’s sled? Who’s Bob?”

“Shhh!”

“What does it mean?”

“I want a refund.”

“Frankly, my dear, I don’t give a show stub.”

“That’s the ticket.”

“Shhh!”

Wait! There’s more. ☞

21 January 2023

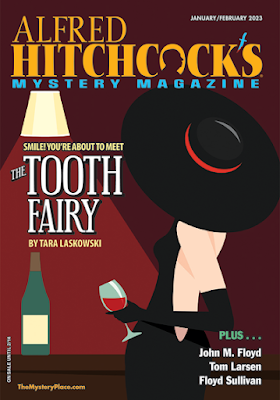

A Cold Case

by John Floyd

Those of you who know me well know I'm not fond of winter weather. My friends in northern climes often say, to irritate me, "I love the changing of the seasons." Well, I love it too, when it changes to spring. I get cold just writing about wintertime, which is something I did for my latest story in Alfred Hitchcock's Mystery Magazine.

"Going the Distance" (Jan/Feb 2023 issue) isn't a Christmas story any more than Die Hard is a Christmas movie, but it happens during that time of the year, and during a freak snowstorm in the Deep South. That's also the home of the three characters in my Ray Douglas mystery series--former lawyer Jennifer Parker, Deputy Cheryl Grubbs, and Sheriff Raymond Kirk Douglas (his father was a movie fan). In this, the seventh installment of my lighthearted series set in the fictional Mississippi town of Pinewood, Ray and his parters in crime(solving) are investigating what could be the attempted murder of a mutual friend. As usual in these stories, my female characters are smarter than the males (I like for my fiction to reflect real life), but the unusual thing is the frigid weather, which complicates everything. Southerners often don't do well in low temperatures, and we especially aren't good at dealing with snow. We don't know how to walk in it or drive in it, and, as I heard someone say the other day, it tends to make shoppers get into fistfights at the Piggly Wiggly.

As it turned out, I had a good time writing this story, because it used a familiar setting and it used characters I've come to know and understand. Best of all, it involved something I've started doing in some of these Sheriff Douglas installments: I try to include several different mysteries in the same story--or at least a lot of different sets of clues that could lead to the solution. The first of the good sheriff's adventures, "Trail's End," uses only one main mystery that the reader can try to solve before the protagonists do, but the second, "Scavenger Hunt," has three separate puzzles in the story. The next three installments, "Quarterback Sneak," "The Daisy Nelson Case," and "Friends and Neighbors," have one mystery each; "The Dollhouse" has two; "Going the Distance" has one, but with many different clues; and the eighth installment, "The POD Squad"--which has been accepted at AHMM but hasn't yet been published--again has three completely separate mysteries in one story. I hope that kind of plot complication makes the story more enjoyable to read; I know it makes it more fun to write. A quick note: "The Daisy Nelson Case" is the only story in this series that has appeared in a market other than AHMM. It was published in Down & Out: The Magazine in December 2020.

This apparent reluctance of mine to write tales set in cold weather is nothing new: I can think of only a dozen or so of my stories that took place during the winter months. One was in Strand Magazine, one in The Saturday Evening Post, several in Woman's World, two in Black Cat Mystery Magazine, several in anthologies, etc.--but the percentage is still small. All writers have quirks, and I guess that's one of mine. I suppose I feel more comfortable and more believable making my characters sweat instead of shiver, unless the shivers are a result of the plot.

The same thing goes for locations. I've never done a tally, but I suspect at least three-fourths of my short stories are set in the American South, which I consider to be Louisiana, Arkansas, Mississippi, Tennessee, Alabama, Florida, Georgia, and the Carolinas. Texas and Virginia are questionable--probably Florida too, for that matter--but I doubt I'd get many arguments about the rest. I've traveled a lot in my years with IBM and the Air Force, and I'm comfortable writing about faraway locations, but I feel absolutely confident writing about my own part of the country, and about characters named Bubba and Patty Sue and Nate and Billy Ray. I went to school with those folks.

How about you? Do those of you who are story-or-novel writers prefer to create stories about things familiar to you or do you enjoy the challenge of setting your fiction elsewhere, or even in different time periods? What do you think are the pluses and minuses of both?

As for me, I'll probably continue spinning tales mostly about my own green and humid corner of the world. I know its people, its towns, its history, its problems--and its weather. Besides, writing about things near my own Zip Code usually means I don't have to do as much research, or go places that require gloves and overcoats.

Matter of fact, I think I'll go adjust the thermostat.

Have a good two weeks.

20 January 2023

Only Immortal For A Limited Time

by Jim Winter

|

| Source: jeffbeck.com |

I'm writing this the day after the great Jeff Beck passed away at the age of 78. Together with the other two Yardbirds legends, Eric Clapton and Jimmy Page, Beck played a huge role in expanding my musical palate. Every kid of a certain age came up on Clapton's blues and country influenced rock, though it's his work with Cream and shortly thereafter that caught the attention of us metal heads. Then there's the lick master, Pagey. If you were a Gen X male in the Midwest, Led Zeppelin dominated your playlists. In fact, I often joke that, in 1989, I had a mullet, all Zeppelin on cassette, and a Camaro. No photographic evidence exists of the mullet. The Camaro died of benign neglect. But Zeppelin when straight to CD as soon as that format became available to me.

At the center was Beck. With Ronnie Wood (later of the Rolling Stones) and Rod Stewart, he formed a sort of proto-Zeppelin.But alas, it was Page and John Paul Jones and, eventually, Bonham and Plant, that went for the heavier sound. Beck turned to his true love, jazz, to reinvent rock and roll, with a whole lotta Miles Davis as inspiration.

And now he's gone. So is Bowie. And Neil Peart. And Charlie Watts. Emerson and Lake, leaving only Palmer. Mick Mars of Motley Crue, who thrilled many of my high school classmates (I was a Deep Purple, classic metal kinda guy. No Ozzy for me. Gimme original Sabbath, who sounded like a garage band. A really good garage band.) had to retire because his joints are freezing up. Chris Squire, the sorcerer on bass, and his partner, drummer Alan White, are gone. I mention this to my brother every time we lose another legend. And he always says the same thing.

"We're getting to the age where we're losing our heroes."

In a way, that's sad. I like to point out that there are still three Beatles alive. Paul and Ringo, of course, but also Pete Best, who's still working. Maybe at a less noticeable level than the two surviving Fab Four, but enough to annoy the hell out of Decca Records.

It's funny because I don't respond the same way to the deaths of other artists the way I do musicians. And I'm not a musician. I probably could have been had I gotten an instrument in my teens and practiced, practiced, practiced. Even 76-year-old Robert Fripp still practices and points at guitarists I would consider lesser talents and say, "Another reason I still need to practice." But I'm not a musician, I'm a writer.

I'm sure Stephen King's eventual demise will rattle my cage. But I did not respond to the loss of Robert B. Parker, Philip Roth, or Sue Grafton the way Tom Petty still has me in mourning over five years later. And actors? Anymore, I can't keep up with the younger ones, and the older ones I often catch myself saying, perhaps tactlessly, "He/She was still alive?" (Alan Rickman was an exception. That one hit hard.)

But musicians are a different breed. They shine brightly in the beginning, achieve a certain level of success that lets them do what they really want, then use the original glory to support their music habit well into old age. (Yes, Willie Nelson is still working in his 90s. I suspect the Stones will be the first centenarian rockers. Well, rocker. They are slowly turning into the Keith Richards Band.)

It does, however, go back to living memory. During my childhood, the echoes of World War II still rumbled loudly, even overwhelming the Cold War. Though my grandfather did not serve, he worked for GM during the war, and many classmates' parents and grandparents served in some capacity, military or civilian. Moreover, our reruns and special guests on sitcoms worked in that era. If the president wasn't a WWII vet - Nixon, Reagan (whose eyesight confined him to Hollywood), GHWB - then they served in Korea: Ford and Carter. But that generation is rapidly disappearing the way the World War I generation vanished before my thirtieth birthday. It might explain the confusion and uncertainty of today. Where do we go next?

For Gen X, especially the older Gen X, along with the youngest Boomers, we have music. Music brought rebellion and freedom in the sixties, unexpected flights of fancy and walls of sound in the seventies, complete reinvention in the eighties, and back to basics in the nineties. And now we're losing the ones who made that happen. That's our living memory. Perhaps in twenty years, reality stars will begin to pass on from something other than excess or accident. Old age, cancer, the next great plague will take them. And Millennials and Gen Z will feel it the as acutely as I still feel the loss of Tom Petty and Jeff Beck.

19 January 2023

The Art (Not Science) of Collaboration

|

| Great collaborators: Miles Davis & Gil Evans |

So I just started a new project. For the first time in decades, I am writing nonfiction for publication.

And that’s not all. For the first time in forever, I won’t be writing it alone.

Of course, no writer writes anything alone. There’s the editor, there are the beta readers, there’s a copy editor, and so on and so forth.

But this one is different. On this one I have a co-writer.

To be honest, I have often wanted to collaborate with another writer when working on my fiction. And I have had promising starts, initial conversations, explorations, and discussions, but nothing has ever really come of it.

That is what makes this different. And I have great hopes for it, not least, because this is the kind of writing project that lends itself to collaboration.

Without saying too much about it, it’s a textbook. Those of you who follow my turns on this blog will remember that over the years I have worn an academic hat in addition to my fiction writing one. And teaching these days, is ever more and more considered a collaborative profession.

And that’s part and parcel of why I have such great hopes for this collaboration: because my co-writer on this book is someone with whom I have spent the past several years collaborating on a shared curriculum. In short, we taught the same subject, same area in the same school.

And we collaborated like crazy.

Over the course of this working relationship, I have come to realize that for me, at least, collaboration is an art, and not a science. I have worked with other teachers, I have planned with other teachers, I have shared curriculum with other teachers.

And while they were all successful, in one way or another, they were not organic, they were not easy, and they didn’t make me feel great. It was more just doing a job.

|

| Am I saying we're on their level as collaborators? I'm not NOT saying it. After all we're even better dressers... |

Not the case with this copilot. We both love our subject area. We are both passionate about it. We share that. And even better, our skills complement each other.

The best part? We naturally divide the tasks required of us when we collaborate it’s really a natural fit. There are things she loves to do that. I don’t mind doing but prefer her results. There are things she loves to do that I have no interest in doing, and definitely prefer her results, and there are things I love to do that she doesn’t mind doing, but prefers my results and … well. You get it.

And that way our collaboration resembles the one I have with my editor. And that we both have our roles to play, but we are definitely cowriters on this. Neither one of us is going to be doing the editing, developmental or copy. For that we have an editorial team we’re working with.

So it’s both like writing a novel, in that the novel is a process, and it’s also not. Because we’re cowriting. I’m not writing, having my editor look at it, rewriting, re-organizing, etc., etc. It just doesn’t work like that.

We’ve even been successful (so far) at divvying up the preliminary work. Again because it’s a work in progress I don’t wanna say too much about it beyond that. But it sure is nice to get to collaborate on a writing project with the cowriter.

So here I am, 25 years into the writing game, and I’m having a new experience. New year, new challenges, right?

How about you? Have you had experience collaborating on your writing? Good ones? Bad ones? Let me know in the comments.

|

| Will our collaborative result rival those of Davis/Evans? Why the Hell not?!? Embrace the possibility! |

See you in two weeks!

18 January 2023

Getting the Best of It

This is my fourteenth annual list of the best short mysteries of the year. It is selected from my best-of-the-week choices at Little Big Crimes. If you cite this list please refer to it as "Robert Lopresti’s ‘Best of the Year’ list at SleuthSayers,” or words to that effect, not as the SleuthSayers' 'Best of the Year' list. Hard as it is to believe, some of the other twenty-odd bloggers here may have opinions of their own.

Fifteen stories made the list this year, one fewer than 2021. Nine are by men, six by women. Two are by fellow SleuthSayers. Six authors have appeared here before.

Alfred Hitchcock's Mystery Magazine provided three stories. Akashic Press, Ellery Queen's Mystery magazine, and the Mystery Writers of America anthology each had two.

Six of the stories are historicals, three have fantasy elements, and two are funny. Okay, enough number-crunching. Let's start tearing open envelopes.

Gina is an inner-city teacher and a genuinely nice person, the kind who makes friends easily with people you and I might cross the street to avoid. When some of these folks notice a van following her in a suspicious manner they react, much like antibodies to an infection. But they are busy and not the best organized crowd, so it is not certain whether the good guys will win...

Bethea, Jesse. "The Peculiar Affliction of Allison White," in Chilling Crime Short Stories, Flame Tree Publishing, 2022.

I have a story in this book.

It is the late nineteenth century in rural New England. A young girl claims her illness is being caused by vampires. The irrational villagers believe her bizarre story and are digging up the graves of the supposed monsters. If her uncle the doctor can't stop this madness corpses are not the only ones who will be harmed.

Braithwaite, Oyinkan, "Jumping Ship," in The Perfect Crime, edited by Maxim Jakubowski, Harper Collins, 2022.

Ida is a photographer, specializing in baby pictures. Her boyfriend wants her to take photos of his new baby. Only catch is, it will be at his house and his wife will be there. She doesn't know Ida is sleeping with hubby. What could possibly go wrong? Very creepy story.

Breen, Susan. "Banana Island," in Mystery Writers of America Presents: Crime Hits Home, edited by S.J. Rozan, Hanover Square Press, 2022.

Marly is a scam-baiter for the IRS, engaging with scam artists, ideally to catch them, but at least to keep them busy so they are not robbing the gullible. She has been engaging with a Nigerian, but can't convince him to ask for money. To raise the stakes she tells him about the situation her family is facing, a real estate mess that has entangled her family. Who exactly are the good guys? Twisty tale.

Breen, Susan. "Detective Anne Boleyn," Alfred Hitchcock's Mystery Magazine, May/June 2022.

You will notice Breen has two stories in my best-of-the-year list this time. Only Brendan DuBois and Jeffery Deaver have managed that before.

An American tourist named Kit is poisoned to death in the Tower of London. Before she can get used to being dead Anne Boleyn arrives. The queen comes across as a tragic figure, very sharp except for her blind love for that nasty husband of hers. The two wronged women manage to help each other out in surprising ways..

Haynes, Dana "Storm Warning," in Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine, July/August 2022.

The inspector's assistant is a beautiful blond woman who looks a lot like Jordan's wife Lizette did when she first met her husband. This does not make Lizette happy. Then a tornado warning forces the characters to retreat to the storm-proof basement. Did I mention that Jordan keeps his firearms collection down there?

Hockensmith, Steve. "The Book of Eve (The First Mystery)," Death of a Bad Neighbour: Revenge is Criminal, edited by Jack Calverley, Logic of Dreams, 2022.

I have a story in this book. This is the second appearance in this column by my friend and fellow SleuthSayer Steve Hockensmith.

Abel has gone missing and his mother Eve is looking for him. The role of Watson is filled by a certain snake. Much of the pleasure here is in the way it's told, the language of the characters. A very funny story that manages to be surprisingly moving as well.

Latragna, Christopher, "The People All Said Beware," in Alfred Hitchcock's Mystery Magazine, September/October 2022.

Latragna, Christopher, "The People All Said Beware," in Alfred Hitchcock's Mystery Magazine, September/October 2022.

It's St. Louis, MO, in 1955. Henry is a professional gambler who works mostly on a steamboat called the Duchess. One day he learns that the ship will be off-limits on Saturday due, according to rumor, to a mob wedding. Henry thinks it odd that the management of the ship would close down on the busiest day of the week, so he begins to investigate. Like a classic John LeCarre tale, or a set of matryoshka dolls, each secret exposed only reveals another secret, right up to the end.

McCormick, William Burton. "Locked-In," in Alfred Hitchcock's Mystery Magazine, January/February 2022.

This is the fourth time McCormick has made my best of the year column. That ties him at the top with David Dean and Janice Law. McCormick and I sometimes critique each others work before it gets submitted for publication. I saw a version of this story back in 2019.

It's 1943. An insurance man named Jeff has just rented a house in a new city. He accidentally locks himself in the cellar. Now he has to attract the attention of a passer-by who happens to near his lonely alley. But the person he attracts is not interested in rescuing anybody...

McLoughlin, Tim, "Amnesty Box," in Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms, Akashic Press, 2022.

McLoughlin, Tim, "Amnesty Box," in Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms, Akashic Press, 2022.

The publisher sent me a copy of this book.

The protagonist is a postal service police officer in New York City. To speed up the occasional metal detector check they must run on post office customers he invents the Amnesty Box. Customers can drop into this cardboard box anything they know they shouldn't be taking through the metal detector. The catch is they won't get the dumped items back. "Even on a slow day we would collect a couple small bags of weed and a few knives." A harmless-enough trick until something much more dangerous is dumped in the box...

Jonathan Stone, "The Relentless Flow of the Amazon," in Mystery Writers of America Presents: Crime Hits Home, edited by S.J. Rozan, Hanover Square Press, 2022.

It is the beginning of the great lockdown, "the time of boxes. Everything delivered." Annie and Tom, new to their suburban neighborhood, are getting tons of boxes which they leave in their garage to give the virus time to wander off.

One day they get an Amazon box they are not expecting. It contains two plastic but clearly real guns...

Subramanian, Mathangi "On Grasmere Lake," in Denver Noir, edited by Cynthia Swanson, Akashic Press, 2022.

Vincent, Bev. "Cold Case," in Black Cat Mystery Magazine, Issue 12, 2022.

Vincent, Bev. "Cold Case," in Black Cat Mystery Magazine, Issue 12, 2022.Roger lives in Texas. One frosty morning he finds a dead man sitting on his porch. When the police arrive he refuses to let them into the house, due to COVID fears, which does not endear him to the shivering constabulatory. Roger is retired but not scared of technology, which he uses intensively in his unofficial investigation. Very witty story.

Joseph S. Walker, "More Than Suspicion," in A Hint of Hitchcock, edited by Cameron Trost, Black Beacon Books, 2022.

Walker also made my best-of-the-year list last year.

A small town in Colorado, just after Pearl Harbor. Hannah is the projectionist in the town's movie theatre. Supply chain issues leave her running Hitchcock's classic movie Suspicion over and over. Darlene, new in town, comes to see it almost every night.Darlene hates the film's ending, in which the husband turns out to be innocent and the wife merely imaging the danger she is in. "The end is the only part that's a lie. A pretty lie, but still. He kills her. Of course he kills her." Darlene has a secret. Hannah, it turns out, has one of her own.

Zelvin, Elizabeth, "The Cost of Something Priceless," in Jewish Noir II, edited by Kenneth Wishnia and Chantelle Aimee Osman, PM Press, 2022.

Zelvin, Elizabeth, "The Cost of Something Priceless," in Jewish Noir II, edited by Kenneth Wishnia and Chantelle Aimee Osman, PM Press, 2022.

This is the second appearance here by my fellow SleuthSayer. Zelvin has written other novels and stories about the Mendozas, a fictional family of Sephardic Jews, some of whom sailed with Columbus. This story begins with a letter from a modern Mendoza bequeathing to her granddaughter the family's most precious treasures: a necklace and the documents proving it belongs to them.

Intertwined with this tale is the third-person story of how Rachel Mendoza really acquired the necklace half a millennium ago. Let's say that both women found their way through considerable difficulties.

17 January 2023

Guest Post: You Can Go Home Again

The dream of the Old House is always the same. I’m walking through the woods with my dad; he’s alive and well. Robust. Immortal. I am both the boy I was—scrawny, quiet, hair so blond it’s almost white; and the man I became—fuller of face, quiet, the white now represented in my beard.

We’re walking through the scrub brush of West Texas, along one of the innumerable trails crisscrossing 150 acres of family land. We called this property the Old House. The name stood both for the hunting cabin someone had built there and for the land where it was situated. I’m not sure who named it that; maybe Sidney, my older brother with Down syndrome, took one look at it and said to my dad, “Pop, that’s an old house.” Sid loved going there to enjoy his comic books or listen to his cassette tapes; we all loved it. The Old House was to be our legacy.

|

| View from the Old House’s front porch on a snowy day. |

In the dream, my dad and I are just walking. We have our hunting rifles, but we’ve no wish to disturb the tranquility of these sacred woods. There’s the live oak tree where I nearly stepped on that copperhead. Over there, the entrance to the gully that gets progressively deeper as it runs westward, until you’re walking between lichen-covered boulders taller than houses. These are the woods where I learned at my father’s knee how to skin a buck and run a trotline, as the song says.

It is home; I am at peace.

And I wake up and remember. Dad has been gone since 2007, the victim of a rare bone cancer that began in his skull and touched his brain, and the Old House has been sold. In the final year of his illness, I tried in vain to persuade my dad not to sell the property.

James, no one has mowed the grass around the Old House. It must be waist-high by now. Don’t worry about that. I’ll mow the grass when I can. James, the water pump in the well house needs to be drained before the next freeze. Dad, I’ll take care of it. We need to get you better, first. I’m not going to get better, Son. I don’t want there to be fighting about who owns the Old House. We won’t fight, I promise you. We’ll share it. There needs to be money for Sidney’s care when I’m gone. This will help. Barbara will take care of Sid. Grace, Jon, and I will help her. Don’t sell the Old House, please.

|

| Scale model of the Old House as a birdhouse. |

But my dad’s mind was set, and the Old House was sold. It gave him a kind of peace I didn’t understand, but I eventually accepted. Then on November 15, 2007, Howard Wade Hearn—retired schoolteacher, huntsman, craftsman, veteran of the Second World War, and the best father a boy could hope for—passed away. My sister Barbara and her husband Larry took on the enormous responsibility of Sid’s care, just as they’d promised. The money from the Old House’s sale, in part, helped to pay for an additional bedroom, one just for Sid, and other renovations for my brother with special needs. Maybe that wouldn’t have been possible otherwise; maybe my dad made the right decision.

After the funeral, I returned to Georgetown, Texas, and settled back into my life. I was an attorney with a mortgage, a wife I loved, and a job I tolerated. With my dad’s passing and the Old House’s sale, childhood was officially over. I guess it had been for a while, since I was thirty-six. It might sound strange, but up until that time, I hadn’t felt like an adult. Not really. I hadn’t felt the burdens of life on my shoulders until I became my dad’s executor. I hadn’t felt old.

At fifty-one, I still have dreams about the Old House and the lessons I learned there. Even waking, I find myself thinking about sitting in deer blinds with my dad. We designed and constructed them ourselves, even putting one on telephone poles for a commanding view of a clearing frequented by deer. I sometimes use Google Earth, starting from the I-20 exit for Gordon, Texas, and I retrace from memory the highways and dirt roads leading to the Old House. I could bookmark the location, but I like finding it this way better; it’s like a treasure hunt where you find yourself.

|

| Destroyed by fire. |

Unless I win the lottery, I’ll probably never have enough money to buy the Old House and restore it to the family. Not in this economy. And even if I did, the actual Old House, the hunting cabin, has been destroyed by fire.

My sister, Barbara, and her sons discovered this on one of their occasional drives to West Texas from Fort Worth. Like me, they enjoy recalling the good ol’ days; unlike me, they live close enough to make the actual trip. Every so often, they’d drive by the property, look over the barbed wire fences, and remember. I’m thankful Sid wasn’t with them on that trip; though we miss him terribly, his passing in 2019 at least kept him from seeing his beloved cabin in ruins.

When Barb sent me photos of the rubble, the news was a gut-punch. There was the Old House’s tin roof collapsed over a burned-out husk, the roof I’d helped my dad put on during a windy day when we were both nearly blown off. Oddly, the flames didn’t reach the nearby shade tree, and the horse tire swing my nephews loved still hung from its branches, forlornly waiting for a rider. Seeing those photos, it was like I lost it all over again, and home never seemed more far away.

But sometimes, through writing, you can go home again. In “Home Is the Hunter,” my third entry in Michael Bracken’s Mickey Finn: 21st Century Noir anthology, Joe Easterbrook returns to his roots in the wilderness of West Virginia. When Joe sets foot on the land he loved, his emotions are my emotions. When he recalls hunting with his father, his memories are my memories. And when he rebuilds his father’s hunting cabin, I’m holding the hammer.

This one’s for you, Dad. We’ll be together again one day, and we’ll take that walk.

An Edgar Award nominee for Best Short Story, James A. Hearn writes in a variety of genres, including mystery, crime, science fiction, fantasy, and horror. He and his wife reside in Georgetown, Texas, with a boisterous Labrador retriever who keeps life interesting. Visit his website at www.jamesahearn.com.

Mickey Finn: 21st Century Noir, vol. 3, is available here.