|

| "Lady" Frances Howard: With a Neckline Like This... |

|

| The Earl of Essex in happier times (Post-annulment) |

|

| Nice Hat, Redux: the Earl of Northampton |

|

| Who is THIS mysterious figure? Find out in two weeks! |

|

| "Lady" Frances Howard: With a Neckline Like This... |

|

| The Earl of Essex in happier times (Post-annulment) |

|

| Nice Hat, Redux: the Earl of Northampton |

|

| Who is THIS mysterious figure? Find out in two weeks! |

Lawrence Block is one of our most versatile crime writers. He has won an obscene number of Edgar Awards for both novels and short stories (plus the Grand Master Award). He produces gritty P.I novels about recovering alcoholic Matt Scudder, and frothy comic capers about burglar-bookseller Bernie Rhodenbarr, not to mention gonzo tales of foreign intrigue starring Evan Tanner, who literally can't sleep and fills the endless hours working for lost causes.

And then there's Keller.

John Paul Keller is an assassin with, well, definitely not a heart of gold, but let's call it a rich inner life. In his first appearance, the Edgar-winning short story "Answers to Soldier," the native New Yorker visits a small town in pursuit of a target and falls in love with the place. In other tales he adopts a dog, hires a therapist, and pursues multiple other hobbies. And there is always stamp collecting, the expense of which keeps him hard at the deadly grindstone.

I think of him as the antithesis of Parker, the burglar invented by Richard Stark (actually Block's friend Donald Westlake), who seems to have no life outside of his profession at all, not even a first name. Yes, he has a girlfriend, but other than that he seems to spend all his time smoking and gazing out into the dark night. Even Westlake admitted to wondering what he did with all the money he stole. Oh, and he probably kills more people in the average book than Keller.

When I read that my writerly instincts lit up. What would happen if someone responded to that introduction by saying: "I grew up in Wichita! Which neighborhood are you from?"

Well, Keller being Keller we know what would happen. The happy Kansan would suffer an immediate and tragic accident.

But not every shady character is as fatal as this guy.

In my story Larry (not Block) goes to a dinner party and meets Matt, new to the neighborhood. Matt explains that he is from Topeka.

“I love Topeka," Larry replies. "Spent most of a year there a while back. Met my wife there.”

Matt immediately changes the subject. Hmm... Later Larry tells his wife: "I don’t think he knew Topeka from Tacoma.”

And Larry becomes obsessed with learning Matt's secret, if indeed he has one. But secrets, of course, can be dangerous...

You may wonder: why Topeka instead of Wichita? Because "The Man From Topeka" scans better as a title, of course.

I like to think my story has a Block-ian feel to it. But that's for you to decide.

And finally in honor of Gary Brooker, the voice and composer of Procol Harum, who died last month:

When I started in Dallas, the chief prosecutor of the court to which I had been assigned would often talk about the "hook." He used "hook" as a synonym for criminal, but not just any defendant. The word "old" preceded "hook" either implicitly or explicitly. A hook had to have been through the system a few times. They were usually charged with property crimes. They were always male. (I've dealt with a few female "hookers" but that's something different.) A hook by occupation or misfortune was one of those frequent fliers we see in the criminal justice system. We used the term in Dallas. I've not heard it in Fort Worth.

The term can be misused. Early on in my career, I wanted to sound like a real prosecutor. I recall asking a long-time defense attorney, "what did your hook do?" His "hook" was an 18-year old first-time offender. The lawyer gave me a look that said I wasn't coming across as a grizzled prosecutor, but rather a kid wearing dad's clothes. (It wasn't the last time as an assistant district attorney that I ran roughshod over the language. Perhaps we'll discuss that in another post.)

|

| Joe Gratz, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons |

Here is where it occurs. Let's assume that Defendant Dewayne has been sentenced to community supervision (probation). Defendant Dewayne has failed to report to his probation officer as required. The district attorney seeks to revoke Dewayne's probation. Defendant Dewayne may contest the revocation and force the government to prove the violation. (That's pretty easy to do in the case of reporting. The probation department keeps records of that sort of thing.) Instead, Defendant Dewayne might admit to the violation. In the legal parlance, he pleads "true" to the allegations. Dewayne may admit to the violation but feel that he can explain this big misunderstanding that landed him in jail. He wants to present his justification as part of the plea. It is true...but here is why.

We had the concept in Dallas, I imagine all jurisdictions do. We didn't have the term. We fumbled for a description. True-but is precisely what occurs.

Under Texas sentencing, by statute, felony crimes may be punished more severely if the prosecutor alleges and proves that the defendant had on one or two prior occasions been sent to the penitentiary. In the Fort Worth courthouse, the defendant is "repped." He or she has been pled as a repeat offender. In Dallas, they're "bitched." A defendant is either "low-bitched" or "high-bitched," depending on whether he or she faces one or two enhancement allegations.

The etymology of "bitched" in this context is, I believe, straightforward. A defendant with two prior enhancements is susceptible to being labeled a "habitual offender." Here in Texas, vowels have never been our strong suit. It is a short step from "habitual" to "high-bitch." And if "high-bitch" is two enhancements, then a single enhancement is just lower than that. Logical, ain't it?

Of course it also let us throw profanity around in public. It makes us sound tough and gritty. That's always appealing to people who wear suits for a living.

Until next time.

Last week, my short story "The Bridesmaid's Tale" appeared in Black Cat Weekly, and I shared the news with all three of my friends. Later that same day, one of them congratulated me on how well I captured the thought process of the female lead/narrator. I thanked him, but I'm not sure I really did it that well.

His comment made me curious enough to go back and look at all my published work, though, which took about five minutes. Most of my novels use multiple-third point of view, and the majority of those characters are male. There are exceptions, of course: both Roller Derby novels have several scenes in the POV of various skaters, and Megan Traine and Beth Shepard get screen time in the novels with their partners. Words of Love has three female POV characters, more than any other book, but if you read it, you'll see why.

Strong female characters abound in my short stories, whether they're the POV character or not. I grew up in a family of strong intelligent women, and during my theater years, I usually worked with a female stage manager and often a female producer. My favorite lights designer was a woman who began as a stage manager and became a good director, too. She also wrote at least one good play that I remember.

Women are more interesting because the still prevalent glass ceiling forces them to be more resourceful and flexible to succeed in various professions. They also need more sense of humor to cope with the crap. Many of my characters take a hard look at themselves and understand how they have to change to solve the current problem. Medically, we know women have a higher threshold of pain and a higher resistance to disease (Otherwise, the race would have died out long ago), and they may have a higher IQ.

I've sold sixteen short stories with a female narrator (four not yet published), and many others have a woman who drives the action even if she doesn't tell the story. Women narrate five of the ten stories currently floating in Submission Limbo, too.

It's easier to masquerade as a woman in a short story because the length gives you less room to make a mistake. I try to convey an attitude through dialogue and thought process, and sometimes using kinesthetic perceptions makes that easier. That's psych and teacher jargon, so let me mansplain here.

We process information through one of three primary modes. About 80% of the population is visual, so they watch and look and read to gain their information. Another 10-12% are auditory and listen well. These people remember a lecture or can follow instructions easily (Many of them become teachers). The remaining few are kinesthetic, who learn from doing, a combination of muscle memory and experience. These are the kids who take the game or toy apart on Christmas morning without reading the instructions and figure out how it works by trial and error. Many of them can call up the emotions they felt during an experience long after it happened. These people are often dancers, athletes, or actors.

Most of my women characters are empaths and have a kinesthetic streak. They're aware of their bodies and feel emotions and slights deeply.

Angie, narrator of "The Bridesmaid's Tale," knows that her older sister Bethesda (the Bride) is taller and curvier than she is, AND is Daddy's favorite. Angie accepts that she'll look terrible in the bridesmaids' gowns Bethesda selected for her taller, bustier friends, and takes the hit for the team. Unlike Bethesda, though, Angie doesn't live off the family fortune. She's in med school at Tufts, studying to become a veterinarian, and her academic strengths help drive the plot.

So does her attitude. She and Bethesda have been at each other's throats since they were old enough to walk, but blood still trumps everything else. Angie won't let her sister be put in danger. She's resourceful, devious, and funny. She tells us she was in her teens before she learned her sister (Whom she refers to as "Bitch-G," for "Bitch-Goddess") was named after their mother's city of birth. Before that, she checked the family medicine cabinet to see if she was named after a pill. She learned that "Bitch" was a handy word in a girl's vocabulary when she saw Mom's reaction to it the first time she said it.

My list says nine stories have been sold that will probably appear by the end of 2023, three of them by June of this year. A woman drives the plot in five of them, solving the mystery, doing bad stuff, or sometimes narrating.

Using a person like yourself as the protagonist (or narrator) runs the risk of taking values and ideas for granted and omitting them from the story. Barnes and Guthrie have elements of me, but not many. Featuring women forces me to pay attention. For what it's worth, readers know more about the families (we've met both of them) and backstory of Beth Sehpard, Tori MacDonald and Megan Traine than they do about Zach Barnes, Trash Hendrix, or Woody Guthrie.

On February 24th, Russia invaded Ukraine. Russia expected to win the war in a matter of days since they are so much larger and better equipped than the Ukraine. What Russia did not expect was having Ukraine rally the world to help defend them.

Apart from the geopolitical importance of this invasion, one question is why are so many ordinary people gripped by the story of Ukraine? Because we are indeed gripped, watching the news constantly and protesting in the streets around the world. Something about this war has moved us all. It has moved countries to impose economic sanctions against Russia and send much needed military equipment to Ukraine.

One reason is that Ukraine’s plight is the universal story of the underdog fighting valiantly, like David fought Goliath, and humans are built to be moved by stories.

“The human mind is addicted to stories,” says Jonathan Gottschall, author of The Storytelling Animal (how stories make us human)

“As you cross cultures and move around in history, you find the same basic concerns and the same basic story structure. The technology of story changes—from oral tales, to clay tablets, to medieval codices, to printed books, to movie screens, iPads, and Kindles. But the stories themselves don’t ever change. They have the same old obsessions. And that won’t change until human nature changes.”

This story - the underdog fighting valiantly - has been articulated by many Ukrainians but first and foremost by President Zelensky.

When Russia invaded, President Zelensky turned down an offer to evacuated from Kyiv. Zelensky’s now famous response was, "The fight is here; I need ammunition, not a ride.”

This is truly the story of David entering battle with Goliath, because David did not have to fight but he felt it was his duty to defeat Goliath and, in doing so, save his people from becoming slaves. Certainly, if Russia defeats Ukraine in this war, Ukrainians become owned and subjugated by Russia.

Malcom Gladwell in his book, David and Goliath: Underdogs, Misfits, and the Art of Battling Giants, dissects the battle in a unique way. Gladwell explains that Goliath is huge and frightening but David has the upper hand because he didn’t have the cumbersome armour of Goliath and could be nimble. Most importantly, David had a sling that can kill a target from two hundred yards away.

David wins the battle by doing the unexpected – he runs towards Goliath, who is immobilized by a hundred pounds of heavy armour, and kills him by hitting him in the head with a stone with a velocity of thirty-four meters per second. (122kmph or 76mph)

Gladwell’s perspective is that underdogs win by fighting in unexpected ways that make their opponent’s strengths useless. Goliath’s size, armour and weapons were no match for David’s nimbleness with his lack of armour and heavy weapons, nor was his bare forehead a match for David’s lethal stone sent at high velocity by a sling.

Just like David, Zelensky fought Russia from the start in very unexpected ways. He didn’t flee. More importantly, despite the famed strength of Russia’s information warfare, Zelensky won the information war from the day he refused to flee. He did this by not speaking like a politician. He spoke with the emotion of a man who loves his country and his people. Rather than speaking of strategy, he appealed to the emotion we all feel towards our own countries, our homes and families. He used the most unusual and unexpected tactic of all when fighting a large military power: he asked the world to see themselves in the plight of Ukraine.

Ukraine is smaller, poorer and ill-equipped compared to Russia. To fight a behemoth like Russia seemed impossible but President Zelensky fought by making us all feel like every missile, every tank and every soldier in Ukraine was like a missile, tank and soldier in our country. This sent people into the street to protest the war and moved countries to sanction Russia. How do you fight a rich country? By making it poorer with economic sanctions. How do you fight a better equipped army? By moving the world to send you military equipment.

We are two weeks into a war that Russia expected to win in days and now some are suggesting that Russia might lose.

I know nothing about military strategy, but I do know the power of stories. From ancient times they have shaped our values and the way we act. The story of Ukraine is one of the reasons that the world values Ukraine and wants to act to protect it. They are the underdog, our modern day David, and we too are Ukraine, the underdog, the victim of Russia’s aggression. Every hospital that is bombed, every child that is killed, feels like ours and we all suffer with Ukraine. As we watch David running towards Goliath, fighting a battle in unexpected ways, we suffer and we hope because that’s the power of stories.

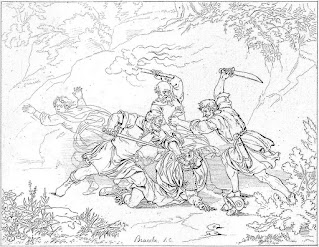

It wasn’t an elaborate murder plot, nor did it go as planned. Not Macbeth’s plan, anyway. He put real thought into it, though. Ambushing his best friend Banquo outside Forres Castle required not one, not two, but three bushwhackers. What happens next is a Shakespeare whodunnit.

Macbeth (or The Scottish Play, for the superstitious) up to this point: Scotland is thunder and fog and war. The ever-hovering Weird Sisters have prodded general Macbeth's ambition with a prophecy that he'll rule Scotland. And Macbeth does, by killing his cousin and legit king, Duncan, and escaping blame with help from Lady Macbeth. But this power couple has a problem: The Weird Sisters also foretold that Banquo's heirs would assume the crown. The Weird Sisters are yet to be wrong. If Macbeth wants to hold and pass that crown, Banquo and his son Fleance's brief candles need snuffing.

Opportunity knocks at Forres Castle, Duncan's old palace. Macbeth freed up everyone's afternoon to relax before a self-congratulatory banquet that night. In actuality, he wants to catch a target alone. Banquo and Fleance, there at court, plan a conveniently lonely ride upon the heath before the banquet. It’s an odd move to leave the relative safety of the other thanes, what with Banquo--and most everyone else--not fooled by Macbeth’s bloody power grab. Banquo must feel most secure keeping himself and Fleance clear of Macbeth.

With cause. Ahead of the ambush, Macbeth tells Murderers One and Two:

With Banquo connected and well-respected, Macbeth needs the job to go perfectly, but he's condescending at best to his crew already onboard. This new op is who Macbeth trusts, someone who knows the local ground and Banquo's riding habits, where he must dismount and walk his horse for the stables.

Enter Third Murderer. It's Third Murderer who positions the bushwhack while First and Second complain about Macbeth’s obvious lack of faith. They have no idea who this new accomplice is, nor is Third Murderer volunteering a name. It’s Third Murderer who spots Banquo, but Fleance scarpers off unwhacked into the heath. Third Murderer notices that, too.

Macbeth never identifies this perfect spy o’ the time. Third Murder just murders thirdly. The simplest theory: Read no critical meaning into this. Often, Shakespearian parts were tossed in to reposition the stage post-scene. But Third Murderer stalks the enduring 1623 script so trusted but so anonymous as if a clue. After all, if the production needed an extra hand to clear the heath, Macbeth could've hire a trio.

|

| Henry Fuseli |

And the play does need a trio. In Macbeth as in life, what's bad comes in threes. Ghostly knocks, incantations, murders on stage (Duncan, Banquo, Macduff’s son). Three was the unluckiest number in Shakespeare’s England. Third Murderer perfecting yet another unholy trinity amps the supernatural unease.

Third Murder perfects something more important: dramatic structure. Up to Fleance's scarpering, everything clicks for Macbeth. He won fame, avoided justice, taken the crown, and consolidated power. After Fleance scarpers, Macbeth suffers desertion and defeat. His hand-picked asset proves imperfect or at least inexpert– Macbeth's pivotal miscalculation and core to the play's message: Rulers turned tyrants will inevitably self-destruct.

Who, then, might be our imperfect spy o' the time?

LENNOX

The thane Lennox tracks after whoever is king. Lennox stays at court longest among the thanes, long after the most forthright have defected to the opposition cause. After Banquo's murder, Macbeth brings Lennox along for a final consultation with the Weird Sisters.

Lennox didn't, however, have motive. He may keep hanging around the palace, but not as a friend to Macbeth. Lennox is repeatedly sarcastic about Macbeth's suspicious rise and Scotland's trail of too-convenient deaths. Soon enough, Lennox joins the rebellion. It's unlikely he seeks or finds welcome there if he third-murdered Banquo.

ROSS

|

| © Wikipedia |

Joel Coen's 2021 movie re-fashions the thane Ross as Third Murderer. It's not the first such interpretation. Ross, a cousin both to Macbeth and poor Duncan, is a wheeler-dealer, in on court gossip and happy to run errands for the crown. The Coen movie fashions Ross into a ruthless king-maker. The botched murder of Fleance intentionally furthers his own ambitions.

A cool take– that doesn't quite jive. In the First Folio (admittedly compiled some 17 years after Macbeth was first staged), Ross breaks with Macbeth early. Ross warns Lady Macduff to flee, at some risk to himself, and Ross tells Macduff about his family's assassination. Ross helps secure English forces to unseat Macbeth. Why murder for a tyrant while tipping everyone else to the body trail?

A DUBIOUS ASSOCIATE

Macbeth was a successful warrior thane prior to the Weird Sisters' appearance. He would've had a network of useful associates and willing mercenaries. Third Murderer as a random agent moves the play along, but Macbeth is also about specific choices leading to specific fates. Even First and Second Murderer get a scene to choose their dark path of revenge for perceived insults off Banquo. It's too loose a thread if Third Murderer is just a mercenary.

SEYTON THE ARMORER GUY

The Scottish-English alliance creeping up forest-style on Macbeth also vow to punish his "cruel ministers." The play shows one such official around for the final battle: Macbeth's attendant and armorer, Seyton. He is introduced late--at the Act V climax--and with little ado. He seems there mostly to provide Macbeth updates on the crumbling situation. But Seyton is all-in with Team Macbeth. His rise to captain might've been launched as a trusted bushwhacker.

A CONJURING

Scotland grows full of eerie happenings as the Weird Sisters run amok. It would've hardly been past the Sisters to place a malevolent entity at Macbeth's disposal. Or perhaps Scotland's hauntings reach a critical mass and conjure their own demons. It's all possible in Macbeth's story world, and such an entity would've seen that fated characters met fated ends: death for Banquo, escape for Fleance, doom for Macbeth. Still, Macbeth had a known someone in mind for third murdering. A random ghoul doesn't inspire the requisite trust.

LADY MACBETH

|

| John Singer Sargent, 1889 (Tate Gallery) |

To here, Lady Macbeth has been clinical and composed about murder. This woman turned to direst cruelty is, at last, someone Macbeth could believe reliable at so great a task.

Directly before the bushwhacking attempt, though, she is at Forres Castle with Macbeth, who hints that it's a shame what might happen to Banquo. Macbeth leaves her with plausible deniability, and he's not interested in discussing her emerging reticence for bloodshed. We next see her entering the banquet with the royal entourage. By all evidence, she stuck to the castle and kept, ahem, her hands clean.

Then, there's theme. Macbeth is overt about gender roles. Lady Macbeth vows to “unsex” herself when she helps murder Duncan. The Weird Sisters are feared doubly for how they defy expectations of womanhood. Even if somehow First and Second Murderers didn't recognize the dang queen as Macbeth's perfect spy o' the time, they would’ve noticed something feminine or unsexed about this new partner.

MACBETH

By this point, Macbeth keeps his own counsel. He came to the throne by violence, and violence to hold power is fine by him. More than anyone, he knows old pal's Banquo’s habits and formidable skills in a fight. A direct part in Banquo's death would further explain Macbeth's sanity break when Banquo's ghost appears--only to Macbeth--at the feast.

But Macbeth, too, arrives at the feast on time and unruffled. If he did slip away and return under the wire, he has to feign surprise when First Murderer reports Fleance's feet-don't-fail-me-now escape. Like Lady Macbeth, though, it’s farfetched to imagine First and Second Murderer not recognizing the king even disguised. They don’t, either overtly or by inference, and as a practical matter, First Murderer wouldn't risk reporting to Macbeth what the boss witnessed in person.

SHAKESPEARE

That's right. The Bard pulled it off. He wrote in Third Murderer with such brilliant vagueness that production options were wide open.In a play about ambition and abuse of power, the suspect list is half the cast. It’s a testament to Macbeth's power that five centuries later we're still sifting through the couldadunnits.

|

| CC 2011 Bradford Timeline |

The OK Corral is an iconic legend of the Old West. But it really didn't enter the public imagination until Earp drifted into Hollywood as what's now called a technical consultant during silent film's heyday. Earp told a screenwriter or a director or possibly even Tom Mix of how he, his brothers, and his consumption-wracked pal Doc Holliday took on a gang of outlaws. Back before Tinsel Town lost the ability to do anything more than remakes or franchises and charge you a second mortgage to see the latest James Bond, they never met a cool story they didn't like.

Nor did a writer named Dashiell Hammett, who decided to adapt the concept for his Continental Op series. The Op, never named, rolls into Personville, Montana, dubbed by the locals as "Poisonville" for its violence and its filthy ground and air from nearby mining. Hammett moves Tombstone north, swaps out the Earp brothers and Holliday for the Op as a solo operator, and uses a recent labor dispute in Butte, Montana (the real-life inspiration for Personville) as a jumping off point.

Thus, the town tamer was born. And it shows up again in the twice-fictionalized tales of Sheriff Buford Pusser (one of Joe Don Baker's surprisingly decent acting turns and a miss for Dwayne Johnson), Jack Reacher's debut (well-adapted for television on Prime), and one of the better latter-day Spenser novels.

What is it about the town tamer that's so intriguing? Earp, after all, was a law man who hired his brothers and deputized the local dentist. Pusser, in the original based-on-a-true-story version of Walking Tall, was a local sheriff.

|

| Source: Amazon Prime Video |

But it's one man taking on the system. And in each of these stories, the system has gotten complacent. Earp may have been taking out a local gang of thugs easily knocked over these days by the likes of The Wire's Stringer Bell or one pissed-off police district (or even a bar brawl that goes horribly awry for them.) The Op took on a mining concern that counted on fear to get its way. Reacher goes after counterfeiters who made the mistake of killing his brother. Spenser knocks over a Mexican gangster who decides he's kingpin from Daredevil (either version. It's the same guy.) Usually, where this happens, someone gets too comfortable with their reign of terror. And one thing that such people forget is that reigns of terror require actual terror. If the one coming at you isn't terrified, the whole thing collapses like a house of cards.

Sometimes that works in real life, but it's a staple of our crime fiction, even scifi and spy thrillers. Someone turns "Boo!" into a superpower, and someone else not really feeling it becomes their kryptonite.

“Evil commonly strikes us not as a problem, but as an outrage. Taken in the grip of misfortune, or appalled by the violence of malice, we cannot reason sanely about the balance of the world. Indeed, it is part of the problem of evil that its victim is rendered incapable of thought.”— Austin Farrer*, Love Almighty and Ills Unlimited

NOTE: Freezing also happens in the face of natural disasters. My husband was in Gulfport, Mississippi during Hurricane Camille, and when it hit, he stood at a plate glass window and watched the winds pick up a semi-truck and throw it directly towards where he was standing. Luckily, it didn't go through the window, just landed right outside. But the point is, he couldn't move. He was hypnotized.

NOTE: Same thing happened with a cousin of Allan's in Ireland during the Troubles. Standing outside a building, having a cigarette, and then a bomb exploded - and the wall behind her went down. She couldn't move. Frozen.

Back in 2014, I wrote a blog about powerlessness and protests in the aftermath of the Ferguson riots. You can read it here: (Absolute Powerlessness)

A few notes on that subject:

Just because Putin attends church on high holy days does not mean he's devout. That used to be the norm for everyone - we've all heard of Easter & Christmas Christians.

And while he is anti-LGBQT, which seems to prove something to "certain people", he's also pro-choice on abortion.

Not to mention that he has people killed (see below).

And then there's the fact that he's declared the liberal ideology that has underpinned Western democracy for decades to be "obsolete."

NOTE to his admirers: in Putin's Russia, there is no freedom of speech, assembly, elections, movement, protest, or anything else - even for you, if you dared to go and live there.

And he has said, “The breakup of the Soviet Union is a national tragedy on an enormous scale; only the elites and nationalists of the republics gained.”

(Last I heard, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, what used to be Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Bulgaria, East Germany, what used to be Yugoslavia, and Albania do not agree with him. And before people write, "Most of those weren't Soviet Satellites!", they were in the Warsaw Pact, each of them had Soviet installed or Soviet friendly governments, and some had Soviet tanks which rolled in to put down any attempts at independence in the 1950s and 1960s. Look it up.)

Back to killing people: Alexander Litvinenko, Putin critic, 2006; Anna Politkovskaya, reporter on Chechnya, 2006; Viktor Yushchenko, President of Ukraine 2005-2010, poisoned 2004 but survived, permanently disfigured; Sergei and Yulia Skripal, father and daughter, 2018 in Salisbury, England but survived (barely); endless journalists, dead. Etc, Etc, Etc.

* Austin Farrer (1904-1968) was an Anglican priest, philosopher, theologian and biblical scholar. He was friends with C. S. Lewis (Farrer gave Lewis communion on Lewis' deathbed), Tolkein and Sayers.

** Denial is also another way to deal with it, but it didn't work for Clarice. An even better example, perhaps, is Daphne du Maurier's short story No Motive: the price always has to be paid.

Previously

in this space, I spoke about beginnings, the hook or hinge of a story, how it presented

itself in the mind’s eye. What, in other

words, made it seem like a story at all, why did it catch our attention? Which got me thinking about endings, and wrapping

things up.

“So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.” That’s a last line that sticks to your ribs.

Bill Goldman once remarked that the first five pages of a script sell the picture. Paul Newman said, OK, but it’s the last five minutes of the movie people walk out talking about. There’s that first rush of adrenaline, when you recognize you’ve opened the door, and you’re about to step through into a place of wonder or certainly surprise, and then there’s the enormous satisfaction of closing it behind you.

Another example: Stephen Crane’s The Open Boat. It begins with the line, “None of them knew the colour of the sky.” (John Berryman argues that, no, in fact it begins with the title, and I have to agree.) And there’s the ending, like a long, indrawn breath, “When it came night, the white waves paced to and fro in the moonlight, and the wind brought the sound of the great sea’s voice to the men on shore, and they felt that they could then be interpreters.” Extraordinary.

In between, of course, there’s incident, and dialogue, fated meetings, and sudden partings, missed opportunities, and the like, but I wasn’t considering process, as such. It’s that when we first look through the keyhole, which is I think Virginia Woolf’s metaphor, possibility clamors. Then, necessity steps in. Each narrative choice we make closes off other variables. At the end, though, when we’re putting the tale to rest, we can tuck in the covers.

Now, in my case, I have a hard time starting a story if I don’t have a title, because the title captures, or projects, a sense of the story as a whole. By the same token, I want the ending to reflect back – not necessarily a twist, but a comment or a glancing blow. For instance, with Aesop, each story points a moral, the Tortoise and the Hare, the Fox and the Grapes. I don’t mean that I want to be cautionary, or prescriptive, or teach a lesson, but I want to draw a line under the story. Think of it as a sort of curtain call.

There’s a Benny Salvador story called “Old Man Gloom,” which takes place not long after the war (WWII, for you young’uns) and goes back to the Japanese internment camps. At the end, Benny takes his daughters upriver to Embudo, to gather fruit.

As

he expected, it was hard work, but satisfying.

The girls, of course, complained to him about it.

Benny

had little sympathy.

Peaches,

he explained patiently, are easily bruised.

This

is very much on the oblique, but as a last line, I thought it was terrifically

effective, the story turning on honor, and obligation, and bitterly damaged

feelings.

Here’s another. At the wind-up of Black Traffic, a spy story, there were half a dozen closing scenes, each of the major players getting a last bow, and the final scene was somebody I figured the reader might have left off their mental list. Oh, yeah, that guy, the Serbian gangster with the blood feud. And the box of chocolates.

To the fallen, in forgotten wars.

The

last line of the book, and it said it all, so far I was concerned. It was about grievance.

I’m using examples from my own stuff, but obviously the Fitzgerald or the Crane are more widely known. I know why I used what I did, and how. I don’t have any particular insight into the other guys. It’s said that Fitzgerald put this passage into the book earlier, in a first draft. I also heard Franklin Schaffner told George C. Scott he wouldn’t lead Patton off with the “No dumb bastard ever won a war by dying for his country” address. Which happens to be a good example of how to round out your picture, without easy irony. “All glory is fleeting.”

The first five pages; the last five minutes.

The season begins with twelve to nineteen chefs competing to be the last chef standing and to be named the “Top Chef.” Sometimes the chefs compete singly and sometimes they compete in teams, and each episode typically features two competitions: a Quickfire Challenge and an Elimination Challenge. The winner of a Quickfire Challenge is often granted immunity in the Elimination Challenge and may win a prize. Though the winner of the Elimination Challenge may also win a prize, the loser of the Elimination Challenge must leave the show.

Much like publication editors, the host (Padma Lakshmi ) and judges (Tom Colicchio, Gail Simmons, and a rotating cast of guest judges) issue a “call for submissions” in the form of a challenge. They provide the competing chefs with a description of what they want, the parameters of the task, and a deadline.

A Quickfire Challenge is much like a flash fiction call for submissions: Create an appetizer using a Milky Way, a prawn, and a kumquat, and do it in twenty-seven minutes. The judges then taste the food, tell the chefs who prepared the worst dishes, who prepared the best dishes, and who won the challenge.

The Elimination Challenges are more complex. The competing chefs must prepare one or more dishes, often to a theme, and often for a crowd of diners. At some point during the season, the chefs are encouraged, or specifically instructed, to “tell a story” with their food.

HOW THIS RELATES TO WRITING

At some point during the first few episodes of season eleven I began to see a parallel to what we encounter as writers. Editors provide us with guidelines that define what genre of stories they want to see, what elements the stories must have, and how many words we’re allowed to use to tell the stories. Sometimes the guidelines are quite specific, and other times they are vague or even nonsensical.

But the parallels become even more apparent when watching what happens at the Judges’ Table after the Elimination Challenges, both the conversations among the judges and their conversations with the competitors when trying to determine which chef gets the boot.

The chefs’ dishes are judged for adherence to the parameters of the challenge, creativity, and technical proficiency. Editors—though the debates are more often internal than among a group of editors sitting around a table—judge submissions much the same way. Does a particular submission meet the guidelines? While adhering to those guidelines, how creative is the final product? And, has the author displayed technical proficiency through proper spelling, punctuation, formatting, and so on?

And one dilemma that the chefs often face when a challenge involves preparing food for several hundred diners: Should they cook for the crowd or should they cook for the judges? During the seasons I’ve watched, food that seemed well-liked by diners has scored poorly with the judges. The lesson, repeated often through the seasons, is that pleasing the judges is critical to winning, just like pleasing editors is critical to getting published.

IT’S JUST A REALITY SHOW

Top Chef is a reality show, so we know the stories told over the course of each episode and over the course of each season must be taken with a large grain of salt. How much is real, how much is staged, and how much of what we see has been manipulated to feed viewers particular story lines? Does it matter?

Maybe not.

But what does matter is something Tom Colicciho says, in one form or another, at least once each season: “We can only judge by what’s on the plate.”

Editors make publishing decisions much the same way. They can only judge your work by what’s on the page.

Ensure that it’s appetizing.

Black Cat Mystery Magazine 11 was released at the tail-end of February, and it contains new stories by Mike Adamson, Lis Angus, Marlin Bressi, Mark Bruce, Leone Ciporin, Veronica Leigh, Anita Murphy, David Rudd, Max Devoe Talley, and fellow SleuthSayers Robert Lopresti, O’Neil De Noux, and Elizabeth Zelvin. It also contains a classic reprint by Richard S. Prather.

Let me start by saying that I'm very fond of Lee Child. He lives about a block and a half from me on the Upper West Side. The first time we met, at a party at the legendary Black Orchid bookstore, I was a mystery writer so green that I asked him who he was.

(I wasn't being disingenuous. I really didn't know.)

We graduated to such collegial contacts as sharing a taxi uptown after an MWA event (he paid) and me standing on tiptoe to kiss him on the cheek in the bar at Bouchercon, back when we did such things. Lee is as tall as Reacher, though only half as wide.

So between my warm feelings for this very nice man and the high regard in which both readers and fellow writers hold his books, of course I gave Reacher a try. Several tries. It's evidence of how they failed to stick with me that I can't tell you which ones, except I remember one of them was the one in which he calls on several old colleagues to help him with the case. I gather this wasn't typical. I guess the writing was smooth and the story told expertly at just the right pace with suspense and twists and whatever thriller readers look for. But what makes a story stick to me is character. I understood that Reacher had it, or he wouldn't have screaming fans like the Beatles and Sherlock Holmes—okay, Holmes fans don't scream, but they're dedicated and enthusiastic, and so are Reacher Creatures. But all I could remember about the guy is that he never washes his underwear. He throws it in the motel trash and buys a new pair at what in my distant youth would have been Woolworth's. Where do you find men's underpants these days? Walmart? K-Mart? Does he need a Big and Tall men's store?

I like characters who have relationships. I gather Reacher usually finds a woman (don't get me started on "the girl" in fiction as a stereotyped place holder, however cunningly disguised as a character with depth). But at the end, he always leaves the woman and anyone else who's become attached to him behind. Like Shane, he rides into town at the beginning and rides off into the sunset at the end. For all I know, Shane never changed his underwear either, but 1950s Westerns didn't share that kind of detail with the audience. In short, Reacher left me cold.

When Tom Cruise optioned the books for the movies, I thought maybe that would help me get a better handle on the character. I heard all the arguments pro and con having an actor so physically unlike the Reacher of the series play the part. Lee Child, the person with the best right to an opinion, was very clear on the subject: one, who was he to turn down a hundred million in box office dollars or whatever the figure was; and two, he saw the books as one artistic entity, the movies as another, created not by him but by the movie makers. I was prepared to like the movie. Sometimes movies illuminate books for me. (Example: Merchant/Ivory's Henry James.) I found the beginning noisy and gratuitously violent. I didn't make it all the way through. So I can't tell if it stuck to the books. I don't know if Cruise developed Reacher's character or kept him a mere action figure.

So that's where I stood on the matter: Lee Child, a sweetheart. Jack Reacher, not for me. And then along came Amazon Prime's TV series, Reacher. This calm giant of a guy walks into a diner, orders a piece of peach pie, is just about to take a bite when the cops come blazing in. Reacher doesn't say a word. He doesn't take a bite. He doesn't run. He doesn't push over the table and assault the cops. He doesn't run his mouth. He sits there maintaining the most eloquent silence I've seen on TV since...hmm, what springs to mind is Jack Benny, a very long time ago, thinking over his options when the bandit says, "Your money or your life!" And I'm in love. Just like that, I finally get Reacher.

For Reacher, violence is the last resort. He never starts it. Well, almost never, unless getting the drop on the very bad guy is absolutely essential. There's been a lot of talk about the violence in the Reacher TV show. There is a very high body count, and bones get cracked both ante and post mortem. But I'd rather watch Reacher gouge and head butt and break bullies and conscienceless killers in pieces than watch serial killers slit the throats of women, which happened twice on the Swedish show Modus on high-minded PBS in the first episode (or maybe two), after which I stopped watching it, but I didn't hear anybody complain about that. Reacher knows how to wait. He cares about the details, using his encyclopedic knowledge, keen observation, and reasoning powers to work a case. He even has a sense of humor, though you have to watch closely to see that little quirk at the corner of the perfectly cast Alan Ritchson's mouth.

I can't wait for Season 2 of Amazon's Reacher. And Lee Child is an executive producer on the show. So I won't feel guilty if I never get back to the books. And kudos to Lee Child for Reacher's success, whatever form it takes.

|

| Kristen Bell |

The Woman in the House Across the Street from the Girl in the Window…

It sounds like an answer sheet absent punctuation from a John Floyd quiz. Instead, it’s the title of a Netflix series. Although I dodged it for a while, I was pretty sure I knew what I was getting into.

(As long as we’re mentioning quizzes, if you’ve seen the series, what are some of the novels and movies they’re parodying?)

Windows 2022

It began with Jimmy Stewart’s spying-out-the-window genre perfected by Hitchcock. You know the one, Perry-Mason-gone bad, often mimicked, never equaled. But perfection doesn’t stop writers and movie-makers from trying.

TWITHATSFTGITW parodies the many novels turned into made-for-TV movies. Kristen Bell plays Anna, an alcoholic Veronica Mars. She embraces the rôle seriously and she makes it work. The characters, the writers, the directors… they make the result hilarious. Not laugh-out-loud funny, but an appreciation of the craft and the skewering of tropes that just… (stab) won’t… (stab) die.

|

| Mailbox Technologist |

And yet, the series is controversial. One (amateur?) movie reviewer hated it intensely, calling it immoral, foul, and raged about rampant nudity throughout, including “shirtless men, women in undergarments.” (gasp!) I vaguely recall one scene with nudity, but most of the outrage came from those who didn’t understand it was a parody. Sheesh, folks. Read the fourteen word title! (An exception was Yahoo’s critic– bless her candor– who admitted up front it took her several episodes before she caught on, and then she liked it.)

Let’s just say I figured out the murderer, more a guess than a deduction because I was getting into the twisted minds of the show runners. That penultimate scene broke a major rule of mystery writing. And I think it was episode 3 that didn’t merely shatter a similar rule, it crushed it, crumbled it, pulverized it, demolecularized and obliterated it. Even my bent sense of humor went, “I don’t believe they did that.” And yet, it was perfect, absurdly perfect.

Setting aside the torch I carry for Veronica Mars,† my favorite character was the mailbox technologist who, day after day, wrestled to get it working right, even entirely dismantling it to start all over. It’s one of those sly bits along with the novels Anna reads, like The Woman Across the Lake, and that Anna has poured so much wine, she can brim a glass to the very drop.

I can’t reveal more except to say by the end of the show, she gives up wine.

For vodka.

Quiz Answers

Not counting the granddaddy of the subgenera, The Rear Window, what are some of the novels and movies TWITHATSFTGITW parodied? These are suggestions mostly from The Independent:

|

| Kristin Bell and Jameela Jamil |

What do you think?

† Okay, okay, so Jameela Jamil made my heart pound and my blood pulse in The Good Place. Or the Bad Place. It was the script, see. Yeah, the script.

Those of you who know me know I like Westerns. I like the time period, the geography, the characters, and the often well-defined line between right and wrong. An extra attraction for me as a writer is that when I write a Western I don't have to worry about whether to mention Covid. Small pleasures . . .

The fact is, Western mysteries have been good to me--I've recently sold Westerns to AHMM, Pulp Modern, Crimeucopia, and The Saturday Evening Post, and two of my latest three stories to appear in Mystery Magazine have been of the horse-opera persuasion. My very latest, called "Lily's Story," is featured in MM's current (March 2022) issue.

"Lily's Story" is really two stories in one. The first involves a pair of newspaper reporters from back East who arrive in a California town on an assignment and then discover that a legendary outlaw is also in town and planning a bank heist. The story-within-the-story is told by another of the characters--the owner of a local restaurant--and involves travelers on a wagon train to Oregon some thirty years earlier--a group that has a fateful encounter with a band of Indians. What I'm saying is, "Lily's Story" is one of those "framed" double-story narratives that I sometimes like and sometimes don't, because they sometimes work and sometimes don't. If you read this one, I hope you'll enjoy it.

My second most-recent Western was "Bad Times at Big Rock," in the January 2022 issue of Mystery Magazine. If that title sounds familiar, it came from my fondness for an old Spencer Tracy movie called Bad Day at Black Rock. The story and the movie are nothing alike except for the title, though--my story's set many years later and farther east, and features weirder characters and more violence and even a paranormal element, which is unusual, to say the least, for a mystery/Western. Plotwise, it's about a brand-new settlement in the middle of the desert that gets taken over by two killers, and the townsfolks' struggle to reclaim their lives and property. It's also a far different kind of tale from "Lily's Story." For one thing, "Bad Times" is told from the POV of the good guys; in "Lily" there aren't many good guys. (But both stories were great fun to write.)

What's your opinion, about setting mystery/crime stories in the past--whether it's the Old West or another historical period? Have you written and sold any? How about (specifically) Westerns? Personally, I've found that some of the best recent mysteries I've read were period pieces. In one sense, they're harder to write well because of all the details that must ring true, but there's a certain fascination in reading (and sometimes learning) about the way things were done--and the way justice was served--in the distant past. Again, it all boils down to whether the plot and characters are interesting, and when they are I think historical fiction can be spellbinding.

Whatever you're writing/publishing, whether it's literary, genre, or mixed-genre, I wish you the best.

Now . . to those kind friends who have expressed concern about me: I'm doing fine, just been laid up for a bit. Thank God for wives who are nurses and offspring who are physicians. They not only know what they're doing, they're willing (to a point at least) to put up with husbands and fathers who are difficult patients. Many thanks also to those who've sent me well-wishes--I hope to be back up to speed shortly. Meanwhile, I'll see you back here in two weeks.