But wait—

Yes, I know it’s not even Thanksgiving, and you’re probably appalled at the thought of me raising the specter of Christmas. But due to supply-chain issues, the words I wanted to use to talk about Christmas books are in short supply worldwide, so I’ve been advised to order those words early, get them shipped to the house, and them sprinkle abundantly in my prose throughout November instead.

Word of caution: The words very and just are quite plentiful in the market right now, so when in doubt, just use very. Just use it very very much. In short supply this season: decency, compassion, and common sense. On the other hand, unfortunately the U.S. is overstocked with stupidity, demagoguery, and mendacity, so feel free to use those words until we have eradicated the surplus.

But seriously, I thought it might be fun to share with you some books I have enjoyed in recent holiday seasons.

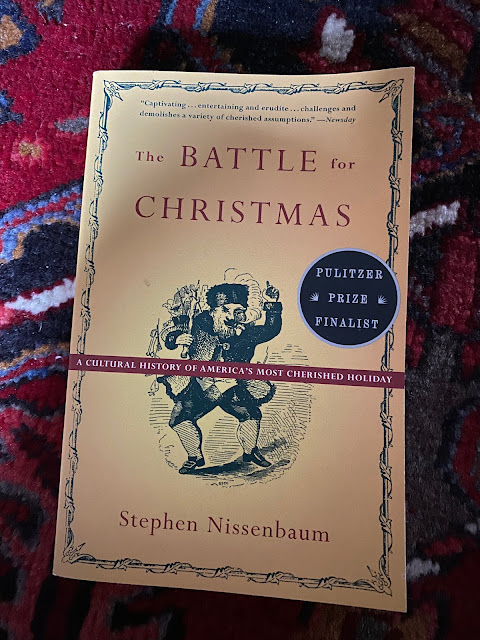

The Battle for Christmas: A Social and Cultural History of Our Most Cherished Holiday, by Stephen Nissenbaum (Knopf, 1996, 381 pages).

This is a brilliant nonfiction history of the American Christmas tradition, even if it is woefully mistitled. I like the book because it demonstrates convincingly that Christmas in America in the early 19th century was a distinctly low-key affair. Using the diaries of New England women, Nissenbaum reveals that the most these diarists did to celebrate the holiday was attend church, and lay in unusual pantry ingredients so they could bake a special cake for their families and visitors. Only later, mid-19th century, do we see Christmas celebrations necessitating the purchase of gifts, first for children, and then of course for every freaking person in one’s social circle. The creation and development of the American Santa Claus plays a major role in crassly forcing the holiday to swing toward commercialism. The book also blows your mind with a discussion of the selfish roots of philanthropy. You watch as wealthy New Yorkers donate money to feed the poor, then assemble in coliseum-like settings to watch as starving children stuff their faces. The last chapter, on the African-American Christmas traditions that grew out of slavery, is also fascinating.

Christmas: A Biography, by Judith Flanders (Thomas Dunne/St. Martin’s, 2017, 256 pages).

Flanders is best known in the mystery community for her novels and a book she did on how the Victorian obsession with crime arguably engendered mystery and true crime literary traditions. She also did a wonderful book on Dickensian-era London. This book, about the origins of Christmas as an international holiday, is rich and head-spinning, chiefly because, as she says, the way people celebrate Christmas in other nations will always seem alien to outsiders. Americans think they have a cultural lock on Santa Claus, but they have no freaking clue about how the gift-bringer tradition plays out in other cultures. Yule lads in Iceland, la Befana in Italy, to name two easy examples. I like this book quite a bit, but I’ll never understand why her publisher did not include the footnotes so you can easily flip to a historic source in the back if you’re intrigued by something she says. (Full footnotes are available on Flanders’ website.) You will enjoy knowing that as long as Christmas has been around, people have been complaining about it. Whether it was too raucous, too commercial, too gluttonous, too heretical, the poor holiday never seemed to please anyone.

A Christmas Memory, One Christmas, & The Thanksgiving Visitor, by Truman Capote (Modern Library, 1996, 107 pages).

I grew up regarding Capote as a comical fixture on the talk shows my parents watched. In high school an English teacher had us read In Cold Blood (why do we do that to kids?) It was only in college that I came to his other writing, which I always found remarkable for its precision. This little classic of three stories is charming because it reminds you how little you truly need to make a holiday special. The best-known story, "A Christmas Memory," boils down to a loved one, a recipe, and some outdoor activity. Extra points if you can figure out Miss Sook’s fruitcake recipe on the basis of Capote’s prose alone. The actual recipe is never given in the book. The author apparently had no use for that conceit, which is now so common to food memoirs.

Seth’s Christmas Ghost Stories, illustrated by Seth (Biblioasis, 2016).

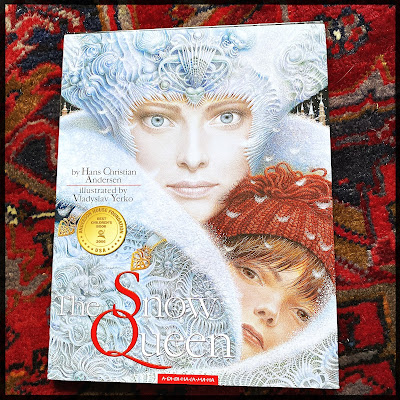

By now most of us know that A Christmas Carol by Dickens grew out of a British holiday tradition which dictated that ghost stories be told this time of year. This delightful little series of books, curated and illustrated by the surname-less New Yorker cartoonist Seth, takes that to a logical extreme. Each volume is a single ghost story by name-brand writers—Edith Wharton, Dickens, etc.—that are suitable for gift-giving and reading in front of the fire. The Wharton book, which I received from a friend, is a mere 37 pages. The complete series currently runs to 11 titles, about $7 in paperback or $0.99 each in ebook form. And when I describe the books as little, I mean that literally. They’re about 4-by-6-inches in size. I wonder if some clever editor (or Seth himself) had visions of Christmas stockings in their head when they conceived the series.The Snow Queen, illustrated by Vladyslav Yerko

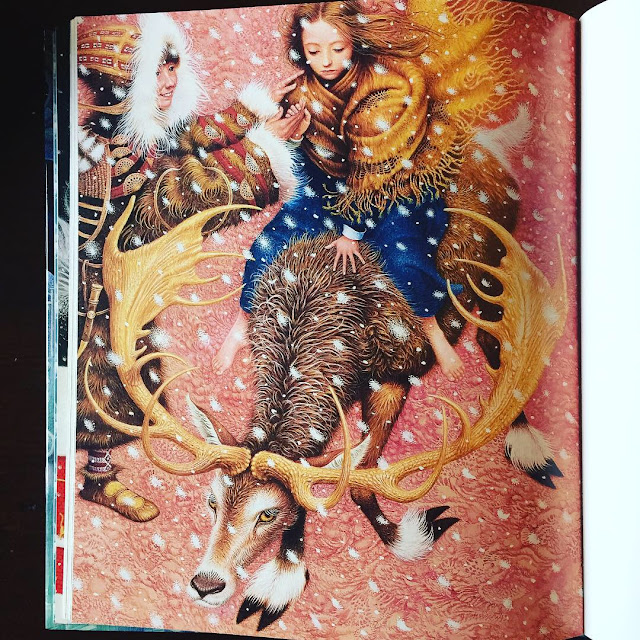

I’m not a fan of this particular tale by Hans Christian Andersen, but the adaptations I’m recommending here are something entirely different. As far as I know, these books were pubbed by two separate houses, one as a 32-page version (top) with prose by an unnamed translator, and another as a more luxurious, slipcased 96-page retelling by Nicky Raven (bottom). Both versions showcase glorious illustrations by the Ukrainian illustrator, Vladyslav Yerko, who in his fanciful bio tells us that as an infant in Kiev he slept in a large suitcase in his grandmother’s home. Yerko’s Snow Queen books were pubbed in multiple languages, but are now out of print. (Still, new and used copies turn up on Biblio and Bookfinder, but always confirm that you are buying an English-language version before checkout.) When I was a lowly intern starting out in publishing, one of my editors at a New York arts magazine subjected me to a lecture in which she insisted that illustrations (which I grew up loving) could never approach the realm of fine art. I flip through the longer of Yerko’s two Snow Queen books every Christmas just to mentally bash that notion to pieces. Behold, folks, I give you Yerko, fine artist and illustrator!

See you in three weeks.

Joe

josephdagnese.com