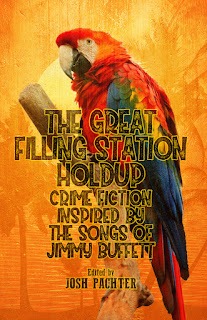

Our friend Josh Pachter has appeared in these pages before. He won the 2020 Short Mystery Fiction Society’s Golden Derringer Award for Lifetime Achievement. In addition to writing and translating, he edited The Great Filling Station Holdup: Crime Fiction Inspired by the Songs of Jimmy Buffett (Down & Out Books), The Beat of Black Wings: Crime Fiction Inspired by the Songs of Joni Mitchell (Untreed Reads), and The Misadventures of Nero Wolfe (Mysterious Press). He co-edited Amsterdam Noir (Akashic Books) and The Misadventures of Ellery Queen (Wildside Press).

You can find Josh at www.JoshPachter.com

— Velma

- A Note about Remainders

- As kids, we sometimes saw comics or paperbacks with the upper half of the covers ripped off. Those were ‘remainders’, a publisher’s overstock. Likewise, bargain book tables at Barnes & Noble and Walmart are likely remainders too, excess copies deeply discounted by publishing houses. In extreme cases, publishers will ‘pulp’ books, grinding them to powder to be recycled into… books.

Remaindrance of Things Past: A Memoir

by Josh Pachter

Chapter 1: The Remainder Bind

In the Olden Days, BigFive Press would agree to publish your book. Their marketing geniuses would do the math and decide on a first printing of X copies. In principle, those copies would all sell, and BigFive would go to a second printing—and then a third, and so on ad infinitum, until you were wealthy enough to buy a little cottage on the Sussex Downs, where you could keep bees and lord it over your serfs.

In practice, though, what was much more likely to happen was that BigFive would wind up with unsold copies of your baby. Those copies took up valuable warehouse space, and if BigFive later needed that space for newer books, they would “remainder” the remaining copies of yours.

That meant that they would sell your leftovers to Wal-Mart or one of the other big-box retailers for pennies on the dollar, and Wal-Mart (or whoever) would dump them into a big bin—the dreaded remainder bin—priced higher than what they paid for them but way lower than the original retail price.

So, for example, let’s say I opened a vein and poured onto the page my magnum opus, Gone Girl With the Wind in the Willows. BigFive would slap a retail price of $20 on it and print five thousand copies. Only three thousand of those copies would sell: two thousand to liberries (remember liberries?) and a thousand to my mother, who would give them away as Christmas presents.

That meant that BigFive would be stuck with two thousand copies of a book they couldn’t sell. Those copies would sit in the warehouse for a while, until BigFive needed the shelf space for the eighth novel James Patterson “wrote” that month. At that point, they’d dump their remaining stock of GGWTWITW onto Wal-Mart for, say fifty cents a copy, and Wal-Mart would mark them up to two bucks apiece and toss them in the bin.

A win-win situation, right? BigFive got rid of some books they didn’t want to continue to warehouse, Wal-Mart cleared a three-hundred-percent profit on every copy they sold, and the customer got a $20 book for a tenth of its retail price.

Wait a second, that’s actually a win-win-win: everybody wins!

Well, almost everybody. The one loser would be me, since instead of earning a royalty of two bucks a copy (ten percent of the retail price), I’d only get a measly five cents a copy (ten percent of BigFive's remainder price)—and then I’d have to give fifteen percent of that to my agent, leaving me four and a quarter cents a copy for a book that ought to have earned me forty times that amount.

So I guess we’d have to call Remainderama a win-win-win-lose situation, with the author the one and only loser.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Chapter 2: Remaindeus Unbound

Those Sayers of the Sleuth who know me—or know of me—were perhaps surprised a couple of years ago when, all of a sudden, out of nowhere, I suddenly began editing anthologies.

Since 2018, in fact, I've done eight of them for six different publishers with

more on the way:

- The Beat of Black Wings: Crime Fiction Inspired by the Songs of Joni Mitchell (Untreed Reads)

- Only the Good Die Young: Crime Fiction Inspired by the Songs of Billy Joel (Untreed Reads)

- The Great Filling Station Holdup: Crime Fiction Inspired by the Songs of Jimmy Buffett (Down and Out Books)

- The Misadventures of Ellery Queen (Wildside Press)

- The

Further Misadventures of Ellery Queen (Wildside Press)

- The Misadventures of Nero Wolfe (Mysterious Press)

- Amsterdam Noir (Akashic)

- The Man Who Read Mysteries: The Short Fiction of William Brittain (Crippen & Landru)

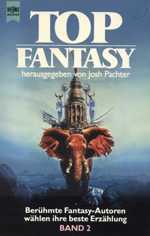

My emergence as an anthologist wasn’t exactly “out of the blue,” though. Forty years ago, I was living in Amsterdam, and I edited half a dozen anthologies for a midsized Dutch publisher, Loeb Uitgevers. Loeb marketed four of them—Top Crime, Top Science Fiction, Top Fantasy and Top Horror—internationally at the Frankfort Book Fair, and various combinations of the four titles sold to an assortment of publishers in Europe and the Americas. Heyne Verlag in Germany, for example, did all four books in mass-market paperback editions (TSF in three volumes and TF in two volumes.) Top Crime, Top Science Fiction, and Top Fantasy were published in England by J.M. Dent & Sons in hardcover and paperback, and Top Crime had a US hardcover edition from St. Martin's Press (with one of the worst cover designs I have ever seen in my life, featuring a silhouette of a gun without a trigger — and what did that say about the twenty-five stories in the book?!).

But I digress. A couple of years later, I was living in what was then still West Germany and teaching for the University of Maryland's European Division on American military bases. One day, I got a snail-mail letter from J.M. Dent, notifying me they were about to remainder the last thousand copies of the hardcover edition of Top Science Fiction to W.H. Smith & Sons for something like a quarter apiece—and, as a courtesy to me, they were offering me the opportunity to buy some at that price.

I remember that I was in my kitchen with this letter literally in my hand, trying to decide whether to buy twenty-five copies or fifty to give away as Christmas presents, when my phone rang. On the line was the director of the UMED textbook office: another instructor wanted to use my anthology as the text for a course in the literature of science fiction, but he wasn’t sure where to find copies and wanted to know if I could help.

“As it happens,” I said, “I own all remaining copies of the book, and I'd be happy to sell you as many as you need.”

The caller was hesitant, because (he said) he usually bought texts in enough bulk that the publisher was willing to offer him a discount.”

“How much of a discount,” I asked, “do you usually get?”

Twenty-five percent off the retail price, he said.

“And how many copies do you want to buy?”

A hundred, he told me.

“Well,” I said, “I can give you a twenty-five-percent discount, but I’ll need you to take two hundred copies.”

And I’ll be damned: he agreed!

I hung up and immediately called Dent in London. “I got your letter,” I said, “and I want to buy some copies of Top Science Fiction at the remainder price.”

How many did I want?

“I’ll take all of them.”

There was a long pause at the other end of the line. Finally, the voice asked if I realized how many copies that was.

“Yes, I read the letter,” I said. “I’ll take them all.”

Another pause. Did I realize how much storage space I’d need for a thousand hardcovers?

“Yes,” I said, “I do. I’ll take them all.”

An even longer pause. Did I realize how much the shipping charge for a thousand hardcovers would be?

“If you sell the lot to W.H. Smith,” I said, “you’ll comp them the shipping, so I expect you won’t charge me for it, either.”

And that’s the way we ultimately worked it. I bought a thousand books for two hundred and fifty dollars including shipping, having pre-sold two hundred of them to UMED for something like three thousand dollars plus shipping, making me the only person I’ve ever heard of who actually made money off a remaindered book.

Chapter 3: The Remainders of The Day

There’s a little more to the story.

Over the next couple of years, UMED reordered Top Science Fiction several times … and, each time, I told them the price had gone up. By the time I moved back to the US in 1991, I’d gotten them to buy almost all of my thousand hardcovers—and I’d also picked up the entire remaindered stock of the paperback edition.

I shipped the last of the hardbacks and several hundred of the paperbacks to the US, and I still have some of each in the attic—including one box of paperbacks that’s moved from Germany to New York to Ohio to Maryland to Iowa to Virginia over the last thirty-one years and is still factory sealed.

It’s a pretty cool anthology: twenty-five excellent stories by twenty-five of the greatest science-fiction writers alive in the early 1980s—Isaac Asimov, Ray Bradbury, Arthur C. Clarke, Harry Harrison, Ursula K. LeGuin, Anne McCaffrey, Robert Silverberg, A.E. Van Vogt, Connie Willis, Gene Wolfe, more than a dozen others—each story selected and introduced by its author as their favorite of the stories they’d written up to that point in their careers.

Anybody wanna buy a copy? I make you good price, my friend!