In Casablanca at Sid's (Rick's) just short decades ago, I met this mysterious lady who has more names than I can usually remember, but the one which finally showed up in my '90s bookstore more often was Toni L.P. Kelner. I actually fell in love Sid, her skeleton character. Humphrey Bogart could have carried the part off masterfully.

This wonderful interview with my friend, by Hank Phillippi Ryan, has been reprinted here with permission from Toni L.P. Kelner and the New England chapter of Sisters in Crime.

-Jan Grape

If you want to find Toni L. P. Kelner, go where the laughter is! For so many years, she’s been such a stalwart to Sisters in Crime in every way. Full of fun and jokes and a marvelous sense of humor, sure. But behind all that is the hardest-working woman in showbiz – – with a pedigree of bestselling mysteries and short stories, an Agatha win, an RT Lifetime Achievement Award, an acclaimed partnership with Charlene Harris, and a glorious and talented and loving family. (Including her wonderful husband Steve, another pillar of the SinC community.)

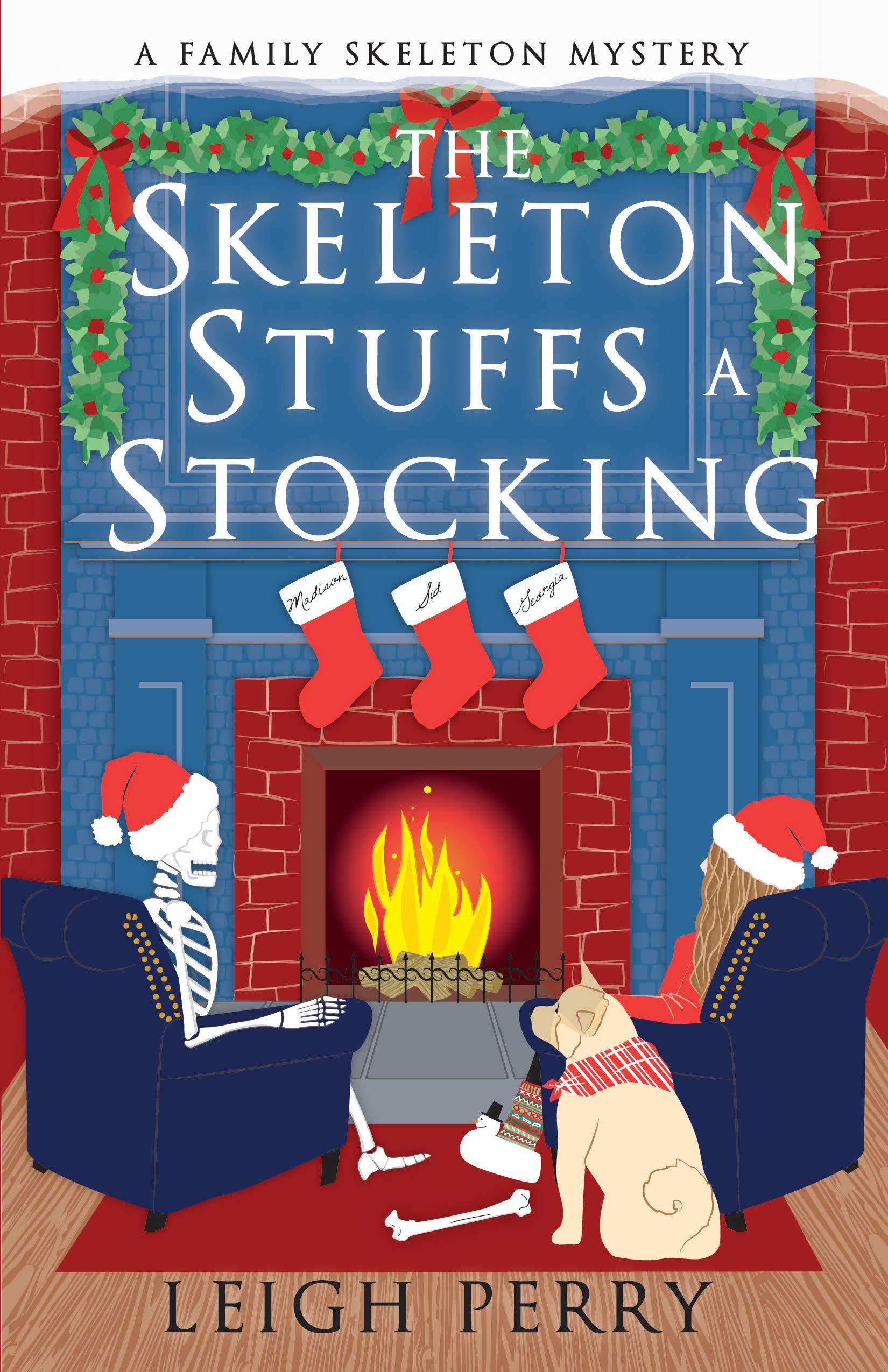

She’s never afraid to take a writing risk, including one super successful series (written as Leigh Perry) starring…a skeleton. Yes, that’s the brave and brilliant brain of Toni Kelner.

HANK PHILLIPPI RYAN: Do you remember the very first time you thought: I’m going to write a book, and I can do it. What was that moment?

TONI KELNER: I first started trying to write when I was in junior high school, and wrote short stories and even a novella along the way, but the first time I really felt pretty confident that I was going to finish a novel would have been late 1988 or early 1989. That’s when I really got going on my first book-length manuscript, and I was sure I’d finish. I didn’t know if it would sell, but it would be an actual manuscript gosh darn it!

HANK: Wow, that’s thirty-two years ago! That’s astonishing. Did that first book sell?

TONI KELNER: Eventually. I wrote it, shopped it around for a year or so while writing another manuscript, then got some great feedback and rewrote the first one. Once I’d finished the rewrite, it only took a few months to get an agent and then a publisher. (I’ve never rewritten or sold that second manuscript, but I will someday.)

HANK: I have no doubt! And that’s so inspirational. How many of your books have been published since then? What do you think about that?

TONI KELNER: Seventeen novels, seven co-edited anthologies, and one collection of my short stories. So I guess that’s 25.

I’m astonished and pleased, but not ready to stop yet!

HANK: Well, of course not! Gotta know, got to ask. Do you outline? Has your method changed over the years?

TONI KELNER: Only if I have to. I do write outlines when editors require it, but find it constraining. Plotting that works in outline just comes off as contrived in the actual writing. When an outline is required, I write it and get it approved, but then stick it in a drawer and ignore it while I write the book.

HANK: That’s wise advice. But I wonder if it gets your brain going, you know? Gets the muse listening? Even if the final book is totally different. Getting that core idea is the hardest for me—how about you? What's the hardest part of the book for you?

TONI KELNER: Getting my tail end writing to get up to speed. Once I’m going, I’m quite fast, but it’s hard to get going.

Once I’m writing, I try not to repeat myself in terms of plot lines and bits of business. That gets harder each book.

HANK: Well, yeah, since you’ve been wring for 32 years! (No pressure.) Is your first draft always terrible? Has it always been?

TONI KELNER: My first drafts are much better than they used to be. With the first few, I started too early. I had to cut out a whole first chapter with my first book, then half a chapter with my second, a few pages with my third… Now I start pretty much where I should start.

HANK: I love that you learn from yourself. Very reassuring. How often in your process do you have doubts about what you’re doing?

TONI KELNER: Almost the entire time except for when I’m rolling down the hill toward the very end.

HANK: What do you tell yourself during those moments of writing fear?

TONI KELNER: I whine to my husband Steve, who reassures me as best he can.

I did recently see something inspirational on Facebook. Another writer—and I can’t remember who—quoted something a friend told her. “You’ve written X number of books and stories. Trust yourself to be able to do it again.”

This came at just the right time, because I’ve got a short story due and have been having a hard time writing during Plague Times.

HANK: Oh, I hear you. If ever there was a time to tune out reality while in the manuscript, this is it. But it’s always safe inside your pages, right? Do you have a writing quirk you have to watch out for?

TONI KELNER: My characters used to grin all the time, but I’ve gotten better at that one. Now I develop a new one per book that I have to catch while editing. Thank goodness for beta readers.

HANK: True. And so funny. Mine shrug and grin. And it’s hilarious--no one in real life does that, right? What’s one writing thing you always do—write every day? Never stop at the end of a chapter? Write first thing in the morning?

TONI KELNER: I write in the wee hours of the morning. I don’t want to—I’d rather get my work done earlier in the day—but for some reason, I usually can’t settle into work until the world quiets down.

HANK: Well, you understand your brain, and let it lead you. How do you know when your book is finished?

TONI KELNER: If I’m editing and change “said” to “asked,” then in the next pass change “asked” back to “said,” I know it’s time to let it go.

HANK: Perfect. Has there been one person who has helped you in your career? (I know, it must be difficult to choose just one, but...)

TONI KELNER: So many, but I’m going to say Charlaine Harris. We had been beta reading each other for a while when she invited me to co-edit anthologies with her. That led to a new very visible stage of my career, a new agent, introduction to an editor and publisher, and so many other opportunities. Thank you, Charlaine!

HANK: Well, she’s a total rock star. And so many sisters have her to thank! Do you think anyone can be taught to be a better writer?

TONI KELNER: I do. I’ve always liked this philosophy from Gideon in All That Jazz:

"Listen, I can't make you a great dancer. I don't even know if I can make you a good dancer. But, if you keep trying and don't quit, I know I can make you a better dancer.”

I think if a writer keeps trying and doesn’t quit, they’re going to get better. Maybe not great or even good or publishable, but better.

HANK: Bird by bird, right? How do you feel about…stuff? Writing swag handouts giveaways that kind of thing. Do you think it matters? Do you have it?

TONI KELNER: I really like creating it but I’m not convinced it works, so I try to restrain myself. I hand out bookmarks, and I’ve got a bunch of microfiber wipes that have original artwork and my book cover on them. Neither are expensive, and both can be mailed with regular postage, so I can still use them during the Plague Times.

Since lots of conventions and charities ask for auction donations, I also buy skeleton-based items on sale to have on hand so I’m ready to do a gift basket at short notice.

HANK: You’ve seen so much change in the publishing industry, what do you think new writers need to know about that?

TONI KELNER: Expect change! Keep an ear out to try to predict what that change will be, but don’t assume the experts are going to be right.

Years back, I was at a Berkley Prime Crime dinner when everybody was buzzing about those new-fangled electronic books, and the editor-in-chief told us that we had nothing to worry about. Ebooks were going to settle down and just be a small part of the field, like audio books. Not only was she wrong about ebooks, but she didn’t expect audio books to become a huge market because of downloading services.

That’s the scary part. On the good side, every change can lead to opportunities. I’ve got books that were long out of print in physical editions, but which are available as ebooks and audio downloads.

HANK: Yeah, you never know. You've been so successful, why do you think that is? What secret of yours can we bottle up and rely on?

TONI KELNER: I don’t think of myself as overly successful, just moderately so, but thank you.

My only secret is being ornery. I just won’t leave. When a series dies, I start a new one. If one story doesn’t sell, I write another one. If I have a dry spell—and I’ve had them—I stick around until it ends. Winning awards, big sales, high-profile deals—those are all great, but staying in the game is the real way to win.

HANK: Yes, yes, yes! We should all print out your advice. (And yes, you are successful!) What are you working on right now?

TONI KELNER: I’m writing my first Family Skeleton short story for an anthology of mysteries inspired by the Marx Brothers, edited by Josh Pachter.

HANK: Oh, Josh is great. He has such perfect ideas! Eager to read that! What book are you are reading right now?

TONI KELNER: The Art of the Con by R. Paul Wilson, which is research for a new series I’m playing with.

HANK: Oh, cannot wait to read that, too! You’ll have to keep us posted. Until then, give us one piece of writing advice!

TONI KELNER: Especially in these times, when sales are sparse because of the world at large, write what you’ve always wanted to write. Even if you don’t sell well, you’ll have a great time.

HANK: Aw, that advice is perfect. Thank you! And sisters, how are you doing? My writing went off the tracks a bit at the beginning of the plague times, as Toni so wisely calls this. Did yours? How did you regroup?

Leigh Perry/Toni L.P. Kelner is two authors in one. As Leigh, she writes the Family Skeleton mysteries, featuring adjunct English professor Georgia Thackery and her skeletal pal Sid. The sixth, THE SKELETON STUFFS A STOCKING, was published in 2019. As Toni, she’s written eleven mystery novels and co-edited seven urban fantasy anthologies with Charlaine Harris. She’s won the Agatha Award and an RT BookClub Lifetime Achievement Award. Her most recent publications were short stories in Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine and in the Nasty Woman Press anthology SHATTERING GLASS, and forthcoming is a contribution to an anthology inspired by the Marx Brothers.

HANK PHILLIPPI RYAN is the USA Today bestselling author of 12 thrillers, winning five Agathas and the Mary Higgins Clark Award, and 37 EMMYs for TV investigative reporting. THE MURDER LIST (2019) won the Anthony Award for Best Novel, and is an Agatha, Macavity and Mary Higgins Clark Award nominee. Her newest psychological standalone is THE FIRST TO LIE. The Publishers Weekly starred review says "Stellar. Ryan could win her sixth Agatha with this one."