by Melodie Campbell (Bad Girl)

Is there an age at which we should stop writing novels? Philip Roth thought so. In his late seventies, he stopped writing because he felt his best books were behind him, and any future writing would be inferior. (His word.)

A colleague, Barbara Fradkin, brought this to my attention the other day, and it started a heated discussion.

Many authors have written past their prime. I can name two (P.D. James and Mary Stewart) who were favourites of mine. But their last few books weren’t all that good, in my opinion. Perhaps too long, too ponderous; plots convoluted and not as well conceived…they lacked the magic I associated with those writers. I was disappointed. And somewhat embarrassed.

What an odd reaction. I was embarrassed for my literary heroes, that they had written past their best days. And I don’t want that to happen to me.

The thing is, how will we know?

One might argue that it’s easier to know in these days with the Internet. Amazon reviewers will tell us when our work isn’t up to par. Oh boy, will they tell us.

But I want to know before that last book is released. How will I tell?

The Idea-Well

I’ve had 100 comedy credits, 40 short stories and 14 books published. I’m working on number 15. That’s 55 fiction plots already used up. A lot more, if you count the comedy. How many original plot ideas can I hope to have in my lifetime? Some might argue that there are no original plot ideas, but I look at it differently. In the case of authors who are getting published in the traditional markets, every story we manage to sell is one the publisher hasn’t seen before, in that it takes a different spin. It may be we are reusing themes, but the route an author takes to send us on that journey – the roadmap – will be different.

One day, I expect my idea-well will dry up.

The Chess Game You Can’t Win

I’m paraphrasing my colleague here, but writing a mystery is particularly complex. It usually is a matter of extreme planning. Suspects, motives, red herrings, multiple clues…a good mystery novel is perhaps the most difficult type of book to write. I liken it to a chess game. You have so many pieces on the board, they all do different things, and you have to keep track of all of them.

It gets harder as you get older. I am not yet a senior citizen, but already I am finding the demands of my current book (a detective mystery) enormous. Usually I write capers, which are shorter but equally meticulously plotted. You just don’t sit down and write these things. You plan them for weeks, and re-examine them as you go. You need to be sharp. Your memory needs to be first-rate.

My memory needs a grade A mechanic and a complete overhaul.

The Pain, the Pain

Ouch. My back hurts. I’ve been here four hours with two breaks. Not sure how I’m going to get up. It will require two hands on the desk, and legs far apart. Then a brief stretch before I can loosen the back so as not to walk like an injured chimp.

My wrists are starting to act up. Decades at the computer have given me weird repetitive stress injuries. Not just the common ones. My eyes are blurry. And then there’s my neck.

Okay, I’ll stop now. If you look at my photo, you’ll see a smiling perky gal with still-thick auburn hair. That photo lies. I may *look* like that, but…

You get the picture <sic>.

Writing is work – hard work, mentally and physically. I’m getting ready to face the day when it becomes too much work. Maybe, as I find novels more difficult to write, I’ll switch back to shorter fiction, my original love. If these short stories continue to be published by the big magazines (how I love AHMM) then I assume the great abyss is still some steps away.

But it’s getting closer.

How about you? Do you plan to write until you reach that big computer room in the sky?

Just launched! The B-Team

They do wrong for all the right reasons, and sometimes it even works!

Available at Chapters, Barnes & Noble, Amazon, and all the usual online suspects.

24 February 2018

How long should we write?

Bad Girl confronts the hard question

Labels:

Amazon,

fiction,

ideas,

Mary Stewart,

P.D. James,

Philip Roth,

plots,

reviews,

writing

Location:

Oakville, ON, Canada

23 February 2018

Style and Formula in The French Connection - a guest post by Chris McGinley

by Thomas Pluck

Let me introduce Chris McGinley, a writer and reviewer whose work has appeared in Shotgun Honey, Out of the Gutter, Near to the Knuckle, and Yellow Mama. We were jawing about one of my favorite films, William Friedkin's classic The French Connection, and he had a lot to say. I thought it deserved a wider audience. --Thomas Pluck

Let me introduce Chris McGinley, a writer and reviewer whose work has appeared in Shotgun Honey, Out of the Gutter, Near to the Knuckle, and Yellow Mama. We were jawing about one of my favorite films, William Friedkin's classic The French Connection, and he had a lot to say. I thought it deserved a wider audience. --Thomas Pluck

Style and Formula in The French Connection

by Chris McGinley

Much has been written about the style and

mood of William Friedkin's The French

Connection (1971). Commentators are

fond of identifying influences ranging from Costa-Gavras' Z and the Maysles brothers work, to the more recently noted

Kartemquin documentaries of the 1960s.

There's been a great deal of talk about long takes, overlapping dialogue

and the film's "gritty" verite

style generally. What's so interesting

to me, however, is how the elements of cinematography and sound establish the

important formal elements of the police

procedural in The French Connection. The scenes unfold in a manner so completely

artful and seamless that we forget we're watching a Hollywood cop film. Indeed, what's unorthodox (and liberating)

about the film is not that it deviates significantly from the procedural

formula, but that the elements of formula are artfully hidden in its style.

The opening Marseilles scene, and the

shakedown at the Oasis bar that follows, establish some narrative basics common

to the procedural. So far, we know we're

in the gritty world of undercover narcs who will most likely encounter

something outside of their usual experience, something international, something

"big." None of this is

especially imaginative or atypical. But

the foot chase that follows the shakedown introduces a few elements unique to

the narrative. First, it initiates a

trope that works in tandem with the visual style of the film, pursuit. Yes, most

cop films involve pursuit of some sort, but pursuit in The French Connection represents something larger. In fact, for Popeye and Cloudy chase is the

heart of investigatory work. They walk,

run, drive, stake-out, ride subways, and generally tail their quarry. Such scenes occupy the bulk of the screen

time. There's precious little gun-play and virtually no tough guy talk in The French Connection. No suspect is ever braced or interviewed

formally. And when there is some

dialogue between cop and con, like at the close of the foot chase scene, the

film seems to make a point about its uselessness. (The "pick your feet in

Poughkeepsie" comment is to this day still an enigmatic remark, and the

cops get nothing important from the pusher they arrest.) But we are introduced to their singular metier: chase.

It's this element that drives the story,

again in some degree like many cop films, but in far greater quantity, and in a

manner that serves the stylistic innovation for which the film is so notable. As viewers, we never tire of the relentless

pursuit, nor do we lament the absence of any profiling, interrogation, cop

fraternity, or even the sex and romance common to so many procedurals of the

era. This is because the formal feature

of pursuit, the detective work at the heart of the film, operates in the service of the film's style, or

look. In the first twenty minutes alone,

Popeye and Cloudy follow Sal and Angie across locations in Times Square, the

Lower East Side, Little Italy, Brooklyn, and the Upper west Side. We get swept up not in the dialogue between

the cops--or in the commission of any actual crimes--but in the locales and in

the way they are presented to us, as naturalistic tableaus often filmed in hand

held shots. Actually, Doyle and Cloudy

say little to each other during this first twenty minutes. They simply follow. The locations, the neon lights, the grey

urban landscapes, and the cars and bridges together form a varied terrain that

shapes the aesthetic of the film and simultaneously serves the formal narrative

function of pursuit/detection.

Interestingly, neither Sal, Angie, nor

Joel Weinstock utters a single audible word by this point, nor have they

committed a crime. Rather, it's the

visual tableau, the film's much-noted "verite"

aesthetic, that propels the narrative, not a criminal backstory or a crime

witnessed by cops, or even a credible lead.

Initially, the cops' boss, Simonson, tells them that they "couldn't

bust a three time loser" with the weak evidence they have on Sal or

Weinstock. And though the first chase

ends in a most uneventful moment that would seem to support his assertion, Sal

and Angie stuffing the newspapers they sell into the front sections, the cops

know that the tail has paid off. It's led

to the Weinstock connection.

The varied landscapes of the film

through which the constant chase is conducted, brilliantly shot in their

natural dreariness by cinematographer Owen Roizman, should also be understood

as a formal narrative element relating to the cops' ability to pursue the criminals.

Until now, the detectives have been confined to Brooklyn, in fact to

Bedford-Stuyvesant, and so they must lobby Chief Simonson for a detachment in

order to make a plea for the case. But Simonson

is reluctant to allow the cops to go beyond their district, and he supports his

logic through chastising the cops who bring in only small time hoods and

dealers, though he concedes that they lead the department in arrests year after

year. At the risk of over-reaching here,

I propose that the expanded geographical jurisdiction, which the Chief wisely

approves in the end, serves the narrative demands of the film as much as it

does the work of Popeye and Cloudy. The

cops need to follow the chase wherever

it takes them. It's what they do:

chase. And it's the chase itself that shapes

the film's distinctive aesthetic--the under-lit interiors and the sunless and

frigid exteriors of the many locations across the city, sites that take the

cops well beyond their usual beat, to places both above and below ground.

It's also clear early on that that

non-diegetic sound is crucial to the formal elements of the procedural in The French Connection. Again, the cops don't do a whole lot of talking. Their continued pursuit of Sal, Charnier, and

Weinstock is characterized by a conspicuous lack

of dialogue, in fact. But it's the score by avant-garde jazz composer Don Ellis

that aids in creating both the tension and movement necessary to narrative

development. It all begins at The Chez,

where Popeye and Cloudy go for a drink on the night they arrest the

pusher. Here again the formal elements

of the genre, in this instance a hunch that leads to a chase, are presented

without much dialogue. Popeye tells Cloudy

he recognizes "at least two junk connections" at Sal's table. But as he locks onto his quarry, the diegetic

music of the Three Degrees' "Everybody's Going to the Moon" fades out

and Ellis' high pitched, electronic dissonance rises. We watch people talk at Sal's table, but we only

see their mouths move. This technique is

repeated in the scene where Popeye keeps tabs on Charnier while he dines at Le

Copain, and in places elsewhere where neither the viewer nor the cops are privy

to an important conversation.

Instead, it's Ellis' atonal score that

heightens the tension in so many of these scenes, creating a narrative momentum

where it wouldn't exist otherwise. For

example, consider again the scene in which the cops first follow Sal and Angie. On the

surface, it's little more than a slow speed tail scene around town. Nothing substantive really happens, and all the cops see is a

possible "drop" in Little Italy and a car switch. At one point, Cloudy nearly falls

asleep. But Ellis' baleful brass notes

and discordant passages are used to enliven the scene, to give it tension and

motion. There's a kinetic feel to it

that belies the slow speed nature of the "chase." I won't discuss in detail the several other

scenes in which the score heightens the action and supports the element of

pursuit, but it happens throughout the long tail of Charnier and company around

town, in the stakeout of the drug car, in the Ward Island scenes, and in other

places.

It's true that there are a few stock

elements of the Hollywood procedural in places, but they seem perfunctory and cliché

(almost bogus by design), and it's not at all clear how they function formally

in the film. Simonson plays the role of

the combustible chief at odds with the detectives in two separate scenes, the

second of which seems entirely unnecessary.

He removes the cops from special assignment, but there are no

repercussions to follow. Popeye is

immediately targeted by the sniper and the case simply resumes without further

comment from the Chief. (The cops never

go "rogue," as it were.) Cloudy

performs some clever detection in places, like in the scene where Devereaux's

car is examined. But such elements are

rare. No, the film constructs its formal

genre elements principally through its style, not through dialogue or the conventions

of the procedural like interviews, profiling, tough-guy talk, or even violence

(of which there is comparatively little).

Together, Ellis' avant-garde score and

Roizman's changing landscapes, themselves a sort of kinesthesis created through

editing, propel the narrative action in a way few other films have ever

done. Simply put, this is why The French Connection is so important to

the Hollywood police procedural. Its

formal elements are embodied in large part through its style, something so

rarely seen either before or since.

22 February 2018

Vancouver Author Sam Wiebe Talks About "Cut You Down"

by Brian Thornton

For today's blog entry it's my pleasure to introduce to you Vancouver crime writer Sam Wiebe. I first met Sam at the 2015 Left Coast Crime conference in Portland, Oregon. We bonded over similar tastes in literature, music and film, and have been pals ever since.. He's coming to the Seattle area next month and appearing in support of the release of a new book entitled Cut You Down.

Now, it's always nice to meet a fellow traveler who makes the same sort of "art" that you make. It's even nicer when the art that fellow traveler produces is the sort of first-rate stuff that Sam Wiebe produces. So we're not only friends, I'm also a fan. Naturally I thought it would be nice to highlight Sam and his work in a blog post in advance of his appearance here next month. He graciously agreed, and the end result you see below. My questions are in bold face.

First, a bit about Sam:

Sam Wiebe was born in Vancouver. He has held a variety of odd jobs, earned an MA in English, published Last of the Independents (2014) and Invisible Dead (2016). His latest is Cut You Down. He has published short stories in Thuglit, subTerrain and Spinetingler, in addition to collecting and editing Akashic Books' forthcoming anthology Vancouver Noir.

And now to the interview:

First, loved both your first novel, Last of the Independents, and your first Wakeland novel, Invisible Dead. Can you comment on how you changed up protagonists between your first and second novel, and let our readers in on why you had to do that?

Thanks! I look at Last of the Independents as my "demo tape." There are things about storytelling I was working out, and not to give away the ending, but that book wraps up Mike's story pretty well. The tone of Invisible Dead was a bit more complex, a bit more grounded in Vancouver history, and I wanted a protagonist who would reflect that. Dave Wakeland is younger than most private eyes--in Cut You Down he's just turned thirty. He was briefly a cop, and spent his youth boxing out of Vancouver's Astoria Gym. In some ways he's a throwback to classic PIs like Lew Archer and the Continental Op, but he's also a young guy trying to make sense of a rapidly changing city. I think of him as the flawed but beating heart of Vancouver.

In your second novel, Invisible Dead, you took what could have been just another depressing missing persons (in this instance the "missing person" being a First Nations–that's Native American for those of us reading this in the States–prostitute named Chelsea Loam) story and really worked it into a superb commentary on the human condition. I felt like we all know a Chelsea Loam, or many Chelsea Loams. And yet she's also such a cypher. How and when did this idea hook you?

I started writing Invisible Dead during the Oppal Commission hearings into the disappearance of hundreds of murdered and missing women, disproportionately low-income, First Nations, and minorities. It's a fraught topic, and it often centres around the serial killers rather than the systemic forces that make people vulnerable. Those hearings were shaped by a very limited narrative of who got to speak and who was to blame. I knew I wanted to write a book that contradicted that. I focused on the disappearance of one woman, Chelsea Loam, as a way to discuss the culpability we all share for allowing people in society to be rendered invisible.

I started writing Invisible Dead during the Oppal Commission hearings into the disappearance of hundreds of murdered and missing women, disproportionately low-income, First Nations, and minorities. It's a fraught topic, and it often centres around the serial killers rather than the systemic forces that make people vulnerable. Those hearings were shaped by a very limited narrative of who got to speak and who was to blame. I knew I wanted to write a book that contradicted that. I focused on the disappearance of one woman, Chelsea Loam, as a way to discuss the culpability we all share for allowing people in society to be rendered invisible.

And it's a theme you have clearly continued to work with in your new book, Cut You Down. So tell us about this new novel of yours.

Cut You Down is the second novel about Vancouver PI Dave Wakeland. He's tasked with finding a missing college student who's mixed up in a school scandal, and who was last seen with a group of suburban gangsters. Adding to that, an ex-girlfriend, police officer Sonia Drego, asks Wakeland to check into the background of her partner, a troubled cop who's been acting strange. The book moves from a rapidly changing Vancouver, to the wilds of Washington State, to a suburban gangland where things aren't what they seem.

I was struck by the outsized role played by the city of Vancouver (and its environs) in Invisible Dead. Setting is a crucial, and all-too-often underutilized, part of fiction. So many great writers have made effective use of setting, rendering it so vivid and affecting that it frequently acts almost like an additional character in their work. Thinking of Dickens' London, Saul Bellow's Chicago, Chandler's Los Angeles, Hammett's San Francisco, David Goodis with Philadelphia, and so on. I feel like you've done a great job of channeling Vancouver in much the same way. Was this a conscious choice on your part, or did it sneak up on you?

It was conscious. A big part of that novel was the disconnect between how much I love Vancouver and how horrific some of the things that go on here are. I always liked the way Ian Rankin handled those sides of Edinburgh--the tourist side and the resident side, the rich side and the side for everybody else. Vancouver is heartbreaking in that way. Cut You Down builds on that disconnect even more, getting into gentrification and displacement, and the lengths people will go to maintain their standard of living.

And Vancouver isn't the only changeable element to this series. Wakeland himself seems far from static:. How did Wakeland change for you this go-round?

He’s forced to deal with more of his past—when his police officer ex-girlfriend asks for his help, it drags up both their relationship, and his brief career as a police officer. Trauma and violence and long buried secrets—he’s got his work cut out for him.

Writing a follow-up to a successful first book is always challenging, in ways writing that first book (a challenge of its own) aren't. Can you walk us through some of these challenges specific to Cut You Down?

Sure. Invisible Dead was a case where I knew the story early on, and the revisions honed that. It’s tighter and better than the first draft, but pretty much the same book.

With Cut You Down, there were a lot of things I discovered during the revisions. It changed drastically, and that process enriched it. For example, the suburban gangsters The Hayes Brothers were introduced late, but I love the element of menace they inject, and the fact that they mirror both Wakeland’s and Tabitha’s stories, as young people trying to make sense of a world where the rules of their parents no longer seem to apply. They’re kind of broken versions of Dave—as he says, what he might have been like if he’d had a few more advantages in life.

Music plays such a huge part in your writing. You're obviously a musician. And you're from a pretty musical family, too, right?

I was a drummer--not sure if that counts as a musician or not! My dad was a studio and club guitarist around Vancouver, playing on the Irish Rovers television show and with the Fraser MacPherson Big Band. He still plays jazz gigs around town.

You know the old joke about what the definition of a drummer is, right? “A guy who beats on stuff and hangs out with musicians”?

I think my favourite is, "How can you tell a drummer is knocking on your door? The knocking speeds up."

Reading your book called to mind the work of the great Irish writer Ken Bruen, who leavens his fiction with musical reference after musical reference, some relevant to the plot, some just shout outs to what the author considers great music. You do a fair amount of this as well. Did these references creep into your work or is this something you've consciously developed?

It's a way to add a sonic element to description, and to give a snapshot of someone's character. I also like throwing in shoutouts to bands from the Pacfic Northwest--in Cut You Down, there are references to Mad Season's Above and NoMeansNo's Small Parts Isolated and Destroyed, among others.

For those of our readers in the Puget Sound area, Sam will be appearing in our back yard in just a few weeks. He's going to read from his new novel on Monday, March 12th, 7 P.M., at Third Place Books in Lake Forest Park You can get more details here).

And that brings us to our last question: Will copies of your other books be available as well?

Third Place will be selling books, and yes, they’ll be in stock!

|

| One of Canada's Finest: Sam Wiebe |

For today's blog entry it's my pleasure to introduce to you Vancouver crime writer Sam Wiebe. I first met Sam at the 2015 Left Coast Crime conference in Portland, Oregon. We bonded over similar tastes in literature, music and film, and have been pals ever since.. He's coming to the Seattle area next month and appearing in support of the release of a new book entitled Cut You Down.

Now, it's always nice to meet a fellow traveler who makes the same sort of "art" that you make. It's even nicer when the art that fellow traveler produces is the sort of first-rate stuff that Sam Wiebe produces. So we're not only friends, I'm also a fan. Naturally I thought it would be nice to highlight Sam and his work in a blog post in advance of his appearance here next month. He graciously agreed, and the end result you see below. My questions are in bold face.

First, a bit about Sam:

Sam Wiebe was born in Vancouver. He has held a variety of odd jobs, earned an MA in English, published Last of the Independents (2014) and Invisible Dead (2016). His latest is Cut You Down. He has published short stories in Thuglit, subTerrain and Spinetingler, in addition to collecting and editing Akashic Books' forthcoming anthology Vancouver Noir.

And now to the interview:

First, loved both your first novel, Last of the Independents, and your first Wakeland novel, Invisible Dead. Can you comment on how you changed up protagonists between your first and second novel, and let our readers in on why you had to do that?

Thanks! I look at Last of the Independents as my "demo tape." There are things about storytelling I was working out, and not to give away the ending, but that book wraps up Mike's story pretty well. The tone of Invisible Dead was a bit more complex, a bit more grounded in Vancouver history, and I wanted a protagonist who would reflect that. Dave Wakeland is younger than most private eyes--in Cut You Down he's just turned thirty. He was briefly a cop, and spent his youth boxing out of Vancouver's Astoria Gym. In some ways he's a throwback to classic PIs like Lew Archer and the Continental Op, but he's also a young guy trying to make sense of a rapidly changing city. I think of him as the flawed but beating heart of Vancouver.

In your second novel, Invisible Dead, you took what could have been just another depressing missing persons (in this instance the "missing person" being a First Nations–that's Native American for those of us reading this in the States–prostitute named Chelsea Loam) story and really worked it into a superb commentary on the human condition. I felt like we all know a Chelsea Loam, or many Chelsea Loams. And yet she's also such a cypher. How and when did this idea hook you?

I started writing Invisible Dead during the Oppal Commission hearings into the disappearance of hundreds of murdered and missing women, disproportionately low-income, First Nations, and minorities. It's a fraught topic, and it often centres around the serial killers rather than the systemic forces that make people vulnerable. Those hearings were shaped by a very limited narrative of who got to speak and who was to blame. I knew I wanted to write a book that contradicted that. I focused on the disappearance of one woman, Chelsea Loam, as a way to discuss the culpability we all share for allowing people in society to be rendered invisible.

I started writing Invisible Dead during the Oppal Commission hearings into the disappearance of hundreds of murdered and missing women, disproportionately low-income, First Nations, and minorities. It's a fraught topic, and it often centres around the serial killers rather than the systemic forces that make people vulnerable. Those hearings were shaped by a very limited narrative of who got to speak and who was to blame. I knew I wanted to write a book that contradicted that. I focused on the disappearance of one woman, Chelsea Loam, as a way to discuss the culpability we all share for allowing people in society to be rendered invisible.And it's a theme you have clearly continued to work with in your new book, Cut You Down. So tell us about this new novel of yours.

Cut You Down is the second novel about Vancouver PI Dave Wakeland. He's tasked with finding a missing college student who's mixed up in a school scandal, and who was last seen with a group of suburban gangsters. Adding to that, an ex-girlfriend, police officer Sonia Drego, asks Wakeland to check into the background of her partner, a troubled cop who's been acting strange. The book moves from a rapidly changing Vancouver, to the wilds of Washington State, to a suburban gangland where things aren't what they seem.

I was struck by the outsized role played by the city of Vancouver (and its environs) in Invisible Dead. Setting is a crucial, and all-too-often underutilized, part of fiction. So many great writers have made effective use of setting, rendering it so vivid and affecting that it frequently acts almost like an additional character in their work. Thinking of Dickens' London, Saul Bellow's Chicago, Chandler's Los Angeles, Hammett's San Francisco, David Goodis with Philadelphia, and so on. I feel like you've done a great job of channeling Vancouver in much the same way. Was this a conscious choice on your part, or did it sneak up on you?

It was conscious. A big part of that novel was the disconnect between how much I love Vancouver and how horrific some of the things that go on here are. I always liked the way Ian Rankin handled those sides of Edinburgh--the tourist side and the resident side, the rich side and the side for everybody else. Vancouver is heartbreaking in that way. Cut You Down builds on that disconnect even more, getting into gentrification and displacement, and the lengths people will go to maintain their standard of living.

And Vancouver isn't the only changeable element to this series. Wakeland himself seems far from static:. How did Wakeland change for you this go-round?

He’s forced to deal with more of his past—when his police officer ex-girlfriend asks for his help, it drags up both their relationship, and his brief career as a police officer. Trauma and violence and long buried secrets—he’s got his work cut out for him.

Writing a follow-up to a successful first book is always challenging, in ways writing that first book (a challenge of its own) aren't. Can you walk us through some of these challenges specific to Cut You Down?

Sure. Invisible Dead was a case where I knew the story early on, and the revisions honed that. It’s tighter and better than the first draft, but pretty much the same book.

With Cut You Down, there were a lot of things I discovered during the revisions. It changed drastically, and that process enriched it. For example, the suburban gangsters The Hayes Brothers were introduced late, but I love the element of menace they inject, and the fact that they mirror both Wakeland’s and Tabitha’s stories, as young people trying to make sense of a world where the rules of their parents no longer seem to apply. They’re kind of broken versions of Dave—as he says, what he might have been like if he’d had a few more advantages in life.

Music plays such a huge part in your writing. You're obviously a musician. And you're from a pretty musical family, too, right?

I was a drummer--not sure if that counts as a musician or not! My dad was a studio and club guitarist around Vancouver, playing on the Irish Rovers television show and with the Fraser MacPherson Big Band. He still plays jazz gigs around town.

You know the old joke about what the definition of a drummer is, right? “A guy who beats on stuff and hangs out with musicians”?

I think my favourite is, "How can you tell a drummer is knocking on your door? The knocking speeds up."

Reading your book called to mind the work of the great Irish writer Ken Bruen, who leavens his fiction with musical reference after musical reference, some relevant to the plot, some just shout outs to what the author considers great music. You do a fair amount of this as well. Did these references creep into your work or is this something you've consciously developed?

It's a way to add a sonic element to description, and to give a snapshot of someone's character. I also like throwing in shoutouts to bands from the Pacfic Northwest--in Cut You Down, there are references to Mad Season's Above and NoMeansNo's Small Parts Isolated and Destroyed, among others.

For those of our readers in the Puget Sound area, Sam will be appearing in our back yard in just a few weeks. He's going to read from his new novel on Monday, March 12th, 7 P.M., at Third Place Books in Lake Forest Park You can get more details here).

And that brings us to our last question: Will copies of your other books be available as well?

Third Place will be selling books, and yes, they’ll be in stock!

21 February 2018

There Was A Wicked Messenger

by Robert Lopresti

I have lots of friends on FaceBook, some of them I have known since childhood and some I wouldn't know if they bit me. That's the nature of FB.

Not long ago one of that latter group contacted me on the FaceBook app called Messenger. It became pretty clear that something shifty was going on and, checking out that friend's FB page I found a note saying "Ignore any messages from him. His account has been hacked." Well, by then I was too interested to ignore them.

Alas, I didn't spot the typos here. (I was in a restaurant wating for lunch to arrive.) I meant to say "I enjoyed their singing but frankly their dancework..."

??? indeed.

At that point I gave up. But if I had sent one more message it would have gone something like this:

I contacted the sponsors and they said they left the names of some winners on the list at the request of the FBI. You see, it turns out some real scumbags are trying to rip off the winners. I hate people like that, don't you? How do they spend all day trying to rob people who never did them any harm and then use those same hands to caress their lovers or comfort their children? How do they talk to their mothers knowing how ashamed those mothers would be if they knew the truth about them? Please be careful, my friend. There is a lot of evil out there.

By the way, a few days after this happened to me the same thing happened to Neil Steinberg, one of my favorite columnists. You can read about what he did here.

I have lots of friends on FaceBook, some of them I have known since childhood and some I wouldn't know if they bit me. That's the nature of FB.

Not long ago one of that latter group contacted me on the FaceBook app called Messenger. It became pretty clear that something shifty was going on and, checking out that friend's FB page I found a note saying "Ignore any messages from him. His account has been hacked." Well, by then I was too interested to ignore them.

Alas, I didn't spot the typos here. (I was in a restaurant wating for lunch to arrive.) I meant to say "I enjoyed their singing but frankly their dancework..."

??? indeed.

At that point I gave up. But if I had sent one more message it would have gone something like this:

I contacted the sponsors and they said they left the names of some winners on the list at the request of the FBI. You see, it turns out some real scumbags are trying to rip off the winners. I hate people like that, don't you? How do they spend all day trying to rob people who never did them any harm and then use those same hands to caress their lovers or comfort their children? How do they talk to their mothers knowing how ashamed those mothers would be if they knew the truth about them? Please be careful, my friend. There is a lot of evil out there.

By the way, a few days after this happened to me the same thing happened to Neil Steinberg, one of my favorite columnists. You can read about what he did here.

20 February 2018

Make Them Suffer--If You Can

by Barb Goffman

Authors in the mystery community are generally known for being nice folks. Helpful, welcoming, even pleasant. But when it comes to their work, successful writers are mean. They have to be.

An author who likes her characters too much might be inclined to make things easy for them. The sleuth quickly finds the killer. She's never in any real danger. In fact, there's no murder at all in the story or book. Just an attempted murder, but the sleuth's best friend pulls through just fine.

These scenarios may be all well and good in Happily Ever After Land. But in Crime Land, they result in a book without tension that's probably going to be way too short. That's why editors often tell mystery authors to make their characters suffer.

Yet that can be easier said than done. If you're basing a character on someone you don't like, then you might have a grand time writing every punch, broken bone, and funeral. But not every character can be based on an enemy. And sometimes characters seem to plead from the page, "Don't do that to me."

It's happened to me. I started writing a certain story a few weeks ago. I had a great first page, and then I got stuck. No matter how I tried to write the next several sentences, they didn't work right. I walked away from the computer. Sometimes I find a break can help a writing logjam. But not this time. In the end, I found I simply couldn't write the story I'd planned because, you see, that plan had included the death of a cat. And I just couldn't do it.

The publication I was aiming the story for would have been fine with a story that included a dead animal. But I wasn't fine with it. And I knew my regular readers wouldn't like it either. Sure animals die in real life, and sometimes they die in fiction too. But those deaths should be key to the story. The Yearling wouldn't work if the deer didn't die. And Old Yeller needed the dog to die too.

I'm going to refer back to these very points if and when another story I've written involving animal jeopardy gets published. Sometimes that jeopardy is necessary for the story. And that's the key question: is it necessary? In the story I was writing about the cat it wasn't, and I knew it in my gut, even if I didn't know it in my head at first. That's why I couldn't bring myself to write the story as planned. Instead, with the help of a friend, I found another way to make the story work, one without any harm to animals.

It's not the first time something like that has happened to me. About six years ago I wrote a story called "Suffer the Little Children" (published in my collection, Don't Get Mad, Get Even). This is the first story of mine involving a female sheriff name Ellen Wescott. She's smart and honest and way different than I'd planned. Originally she was supposed to be a corrupt man. But as I was thinking through the plot during my planning stage, I heard that male sheriff say in my head, "Don't make me do that. I don't want to do that." Spooky, right?

While part of me immediately responded, "too bad,"--he had to suffer--another part of me knew that when characters talk back like that, it's because my subconscious knows what I'm planning isn't going to work. Either it won't work for the readers, as with the cat I couldn't kill. Or it won't work for the plot, as was the case with this sheriff story. So my corrupt male sheriff became an honorable female sheriff, and large parts of the plot changed. My female sheriff faced obstacles, but she was a good person. That was a compromise my gut could live with.

Readers, I'd love to hear about stories and books you've enjoyed that involved a plot event you didn't love, yet you accepted it because you knew it was important to the story. And writers, I'd love to hear about times you couldn't bring yourself to write something. What was it? And why?

An author who likes her characters too much might be inclined to make things easy for them. The sleuth quickly finds the killer. She's never in any real danger. In fact, there's no murder at all in the story or book. Just an attempted murder, but the sleuth's best friend pulls through just fine.

These scenarios may be all well and good in Happily Ever After Land. But in Crime Land, they result in a book without tension that's probably going to be way too short. That's why editors often tell mystery authors to make their characters suffer.

Yet that can be easier said than done. If you're basing a character on someone you don't like, then you might have a grand time writing every punch, broken bone, and funeral. But not every character can be based on an enemy. And sometimes characters seem to plead from the page, "Don't do that to me."

It's happened to me. I started writing a certain story a few weeks ago. I had a great first page, and then I got stuck. No matter how I tried to write the next several sentences, they didn't work right. I walked away from the computer. Sometimes I find a break can help a writing logjam. But not this time. In the end, I found I simply couldn't write the story I'd planned because, you see, that plan had included the death of a cat. And I just couldn't do it.

|

| Don't do it! |

The publication I was aiming the story for would have been fine with a story that included a dead animal. But I wasn't fine with it. And I knew my regular readers wouldn't like it either. Sure animals die in real life, and sometimes they die in fiction too. But those deaths should be key to the story. The Yearling wouldn't work if the deer didn't die. And Old Yeller needed the dog to die too.

I'm going to refer back to these very points if and when another story I've written involving animal jeopardy gets published. Sometimes that jeopardy is necessary for the story. And that's the key question: is it necessary? In the story I was writing about the cat it wasn't, and I knew it in my gut, even if I didn't know it in my head at first. That's why I couldn't bring myself to write the story as planned. Instead, with the help of a friend, I found another way to make the story work, one without any harm to animals.

It's not the first time something like that has happened to me. About six years ago I wrote a story called "Suffer the Little Children" (published in my collection, Don't Get Mad, Get Even). This is the first story of mine involving a female sheriff name Ellen Wescott. She's smart and honest and way different than I'd planned. Originally she was supposed to be a corrupt man. But as I was thinking through the plot during my planning stage, I heard that male sheriff say in my head, "Don't make me do that. I don't want to do that." Spooky, right?

| |

| Sometimes characters just have to be nice |

Readers, I'd love to hear about stories and books you've enjoyed that involved a plot event you didn't love, yet you accepted it because you knew it was important to the story. And writers, I'd love to hear about times you couldn't bring yourself to write something. What was it? And why?

19 February 2018

Why Sara Writes

|

| Sara Paretsky © Steven Gross |

In 1986, I read the first V I Warshawski private eye book, Indemnity Only. I also was writing a female P.I. novel when I learned women mystery writers at Bouchercon were meeting and forming a group called Sisters In Crime. One major objective of SinC was to raise publishing and public awareness of women mystery writers. This organization was the brainchild of V I Warshawski’s author, Sara Paretsky.

In 1988, I attended my first Edgars and Bouchercon. I quickly learned Sara was passionate about women writers getting a fair shake.

In 1990, my husband and I opened a mystery bookstore in Austin. Three years later, we hosted a mystery convention, Southwest Mystery Con. A small group of Austin mystery women formed a chapter we named Heart of Texas Sisters in Crime. Through that, Sara and I became friends. I’m proud our H•O•T chapter of SinC still meets monthly. I’m proud that Sara still fights for women mystery writers. And I’m honored to introduce Sara as today’s guest writer.

Sara Paretsky and her acclaimed P I, V I Warshawski, transformed the role of women in contemporary crime fiction, beginning with the publication of her first novel, Indemnity Only, in 1982. Sisters-in-Crime, the advocacy organization she founded in 1986, has helped a new generation of crime writers and fighters to thrive.

Among other awards, Paretsky holds the Cartier Diamond Dagger, MWA's Grand Master, and Ms. Magazine's Woman of the Year. Her PhD dissertation on 19th-Century US Intellectual History was recently published by the University of Chicago Press. Her most recent novel is Fallout, Harper-Collins 2017. Visit her at SaraParetsky.com

— Jan Grape

Why I Write

by Sara Paretsky

by Sara Paretsky

Years ago, when I was in my twenties, I heard an interview with the composer Aaron Copland. The interviewer asked why it had been over a decade since Copland's last completed composition. I thought the question was insensitive but Copland's answer frightened me: "Songs stopped coming to me," he said.

I wasn't a published writer at the time, but I was a lifelong writer of stories and poems. These were a private exploration of an interior landscape. My earliest memories include the stories that came to me when I was a small child. The thought that these might stop ("as if someone turned off a faucet," Copland also said) seems as terrifying to me today as it did all fifty years back.

I write because stories come to me. I love language, I love playing with words and rewriting and reworking, trying to polish, trying to explore new narrative strategies, but I write stories, not words. Many times the stories I tell in my head aren't things I ever actually put onto a page. Instead, I'm rehearsing dramas that help me understand myself, why I act the way I do, whether it's even possible for me to do things differently. Where some people turn to abstract philosophy or religion to answer such questions, for me it's narrative, it's fiction, that helps sort out moral or personal issues.

At night, I often tell myself a bedtime story- not a good activity for a chronic insomniac, by the way: the emotions become too intense for rest. When I was a child and an adolescent, the bedtime stories were versions of my wishes. They usually depicted safe and magical places. I was never a hero in my adventures; I was someone escaping into safety.

As a young adult, I imagined myself as a published writer. For many years, the story I told myself was of becoming a writer. Over a period of eight years, that imagined scenario slowly made me strong enough to try to write for publication. After V I Warshawski came into my life, my private narratives changed again. I don't lie in bed thinking about V I; I'm imagining other kinds of drama, but these often form the subtext of the V I narratives.

I'm always running three or four storylines: the private ones, and the ones I'm trying to turn into novels. I need both kinds going side by side to keep me writing.

Storylines are suggested by many things- people I meet, books I'm reading, news stories I'm following- but the stories themselves come from a place whose location I don't really know. I imagine it as an aquifer, some inky underground reservoir that feeds writers and painters and musicians and anyone else doing creative work. It's a lake so deep that no one who drinks from it, not even Shakespeare, not Mozart or Archimedes, ever gets to the bottom.

There have been times when, in Copland's phrase, the faucet's been turned off; my entry to the aquifer has been shut down. No stories arrive and I panic, wondering if this is it, the last story I'll ever get, as Copland found himself with the last song. If that ever happens permanently, I don't know what I'll do.

So far, each time, the spigot has miraculously been turned on again; the stories come back, I start writing once more. Each time it happens, though, I return to work with an awareness that I've been given a gift that can vanish like a lake in a drought.

Labels:

Jan Grape,

Sara Paretsky,

writing

Location:

Chicago, IL, USA

18 February 2018

YTD

by Leigh Lundin

Just the facts… believe it or not

- Americans own more firearms than all nations’ armies combined.

- The US is ranked 1st in crime rates among nations.

- The US is 14th among the most dangerous nations in the world.

- America locks up more of its own citizens than any other nation.

- America experiences nearly one multiple/mass shooting per day.

- Americans kill a thousand of their own countrymen every month.

- Gun owners commit suicide at the rate of two thousand a month.

- NRA claims $1-million per day from its 5 million members.

- The NRA-owned Congress says it’s not time to discuss it… ever.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Labels:

crimes,

guns,

homicides,

laws,

Leigh Lundin,

NRA,

ownership,

Statistics

Location:

Parkland, FL, USA

17 February 2018

Draftsmanship

by John Floyd

Offhand, I can't think of many words that have more different meanings than "draft" does. Drafts can refer to breezes, horses, beer, checks, athletics, military service, depth of water, and--yes--preliminary versions of a piece of writing. In other words, you can feel them, harness them, drink them, sign them, get caught by them . . . or write them.

I write a lot of drafts. Mine are usually short, since I write mostly short stories, and the first is often longer than the second, the second longer than the third, and so forth. (I tend to overwrite a bit.) I should mention, too, that my first draft is usually terrible. That doesn't bother me--nobody but me is going to see it anyway--and I think it's better to get as much as possible down on paper than to leave something important out.

I write a lot of drafts. Mine are usually short, since I write mostly short stories, and the first is often longer than the second, the second longer than the third, and so forth. (I tend to overwrite a bit.) I should mention, too, that my first draft is usually terrible. That doesn't bother me--nobody but me is going to see it anyway--and I think it's better to get as much as possible down on paper than to leave something important out.

I also like to write a first draft all the way through, without stopping to do a lot of analysis on the way. I've never been one of those people who "edit as they go." I don't even pay much attention to punctuation or spelling or grammar in those first drafts. They truly are rough.

A writer friend of mine insists that she doesn't have to deal with drafts--and not because she keeps the windows closed. She just makes every page as perfect as it can possibly be before going on to the next. Her reason for doing that is simple, she says: when she's written the final page of her book or story, she's finished; no corrections or subsequent drafts are needed. The reason I don't do that is simple, too: I might later decide to change something in the plot, or add another character, or take one out, or change the POV. If that happens, and if I've already tried to polish the first scenes and pages to a high gloss, that means I'll have to go back and re-edit what I've already edited. I'm not super-efficient and I'm sure not smart, but I'm smart enough not to want to do the same job twice. Besides, getting the whole thing down on paper, start to finish, gives me a warm and comfortable feeling about the project. It makes it something I know I can handle.

Writing a first draft all the way to the end in one swoop isn't as hard as it sounds, because I'm one of those writers who likes to map the story out mentally before I ever start putting words on paper. I think about the plot for a long time beforehand. Again, that doesn't keep me from later making changes, but it does allow me to have a blueprint to follow when I start writing, and having that structure in mind gives me--as I said--a sense of security. You might not do that or need that, but I do. Different strokes. (By the way, if you outline on paper and if your outline is long enough, sometimes that IS your first draft.)

I occasionally don't even have names finalized when I do a first draft. My hero/heroine might be H, my villain might be V, the hero's best friend might be BF. These are just place-holders, so I can come back later and fill in the names. Same thing goes for locations or situations that will require detailed research, or scenes that need a lot of description--I don't spend the time to do that in first drafts. I'm more concerned about plot points and the flow of the story. (Not that it matters, but I've found it's fairly easy for me to write beginnings and endings. It's the middles that are hard. Maybe that's why I write shorts instead of novels.)

Anne Lamott said, in her book Bird by Bird, ". . . The first draft is the down draft--you just get it down. The second draft is the up draft--you fix it up. You try to say what you have to say more accurately. And the third draft is the dental draft, where you check every tooth, to see if it's loose or cramped or decayed or even, God help us, healthy." She also said, "Almost all good writing begins with terrible first efforts."

Anne Lamott said, in her book Bird by Bird, ". . . The first draft is the down draft--you just get it down. The second draft is the up draft--you fix it up. You try to say what you have to say more accurately. And the third draft is the dental draft, where you check every tooth, to see if it's loose or cramped or decayed or even, God help us, healthy." She also said, "Almost all good writing begins with terrible first efforts."

Readers have often asked me how many drafts I write, of a short story, The answer is, it varies. It also depends on how you define "draft." If you go through a work-in-progress and change only one sentence, is that new version another draft? As for me, I don't usually do many extensive re-writes, but I do go back through the manuscript a few times after a third- or fourth-draft polishing and see if there's anything more that needs correcting or fine-tuning. But, as all writers know, you don't want to go over it too much. When you can read through what you've done several times and not find anything glaring, you're probably finished. If you persist too long, you'll get to the point where changes might make things worse instead of better.

How about you? Are you a draft-dodger, and just edit everything as you go? Or do you rehearse and shoot several takes before you print the film? If so, how many drafts does that usually involve? How do you decide how many drafts is too many? How detailed is your first draft? Do you ever outline beforehand, either mentally or on paper? Do you ever write the ending first?

I once heard that a novelist has to be a good storyteller and a short-story writer has to be a good craftsman. Maybe both have to be good draftsmen.

Now, I wonder if I need to do more editing on this column . . .

I write a lot of drafts. Mine are usually short, since I write mostly short stories, and the first is often longer than the second, the second longer than the third, and so forth. (I tend to overwrite a bit.) I should mention, too, that my first draft is usually terrible. That doesn't bother me--nobody but me is going to see it anyway--and I think it's better to get as much as possible down on paper than to leave something important out.

I write a lot of drafts. Mine are usually short, since I write mostly short stories, and the first is often longer than the second, the second longer than the third, and so forth. (I tend to overwrite a bit.) I should mention, too, that my first draft is usually terrible. That doesn't bother me--nobody but me is going to see it anyway--and I think it's better to get as much as possible down on paper than to leave something important out.I also like to write a first draft all the way through, without stopping to do a lot of analysis on the way. I've never been one of those people who "edit as they go." I don't even pay much attention to punctuation or spelling or grammar in those first drafts. They truly are rough.

A writer friend of mine insists that she doesn't have to deal with drafts--and not because she keeps the windows closed. She just makes every page as perfect as it can possibly be before going on to the next. Her reason for doing that is simple, she says: when she's written the final page of her book or story, she's finished; no corrections or subsequent drafts are needed. The reason I don't do that is simple, too: I might later decide to change something in the plot, or add another character, or take one out, or change the POV. If that happens, and if I've already tried to polish the first scenes and pages to a high gloss, that means I'll have to go back and re-edit what I've already edited. I'm not super-efficient and I'm sure not smart, but I'm smart enough not to want to do the same job twice. Besides, getting the whole thing down on paper, start to finish, gives me a warm and comfortable feeling about the project. It makes it something I know I can handle.

I occasionally don't even have names finalized when I do a first draft. My hero/heroine might be H, my villain might be V, the hero's best friend might be BF. These are just place-holders, so I can come back later and fill in the names. Same thing goes for locations or situations that will require detailed research, or scenes that need a lot of description--I don't spend the time to do that in first drafts. I'm more concerned about plot points and the flow of the story. (Not that it matters, but I've found it's fairly easy for me to write beginnings and endings. It's the middles that are hard. Maybe that's why I write shorts instead of novels.)

Readers have often asked me how many drafts I write, of a short story, The answer is, it varies. It also depends on how you define "draft." If you go through a work-in-progress and change only one sentence, is that new version another draft? As for me, I don't usually do many extensive re-writes, but I do go back through the manuscript a few times after a third- or fourth-draft polishing and see if there's anything more that needs correcting or fine-tuning. But, as all writers know, you don't want to go over it too much. When you can read through what you've done several times and not find anything glaring, you're probably finished. If you persist too long, you'll get to the point where changes might make things worse instead of better.

How about you? Are you a draft-dodger, and just edit everything as you go? Or do you rehearse and shoot several takes before you print the film? If so, how many drafts does that usually involve? How do you decide how many drafts is too many? How detailed is your first draft? Do you ever outline beforehand, either mentally or on paper? Do you ever write the ending first?

I once heard that a novelist has to be a good storyteller and a short-story writer has to be a good craftsman. Maybe both have to be good draftsmen.

Now, I wonder if I need to do more editing on this column . . .

16 February 2018

First Stories

by O'Neil De Noux

Michael Bracken's earlier post about his first published story inspired me to go back to my first stories.

My first story to see print was "The Sad Mermaid," a fantasy published in ELLIPSIS, student magazine of the University of New Orleans. Wasn't a sale. No payment. January, 1976. Another beginning writer had her first story printed in that issue of ELLIPSIS - fellow New Orleans mystery writer Tony Fennelly. In 1996, I made a little money on the story when it was published in TALE SPINNER Magazine, Issue 4.

Years of rejections of short stories followed. multi-genre failures. Decided to write a novel and finished GRIM REAPER (1988 Zebra Books). When it sold, I remember telling my father who asked, "They're paying you American money?"

Soon after, I met George Alec Effinger who was living quietly in the French Quarter. He took a look at my short stories and suggested I use the main character from my novel in stories.

First LaStanza story sold quickly -"The Desire Streetcar" Pulphouse Fiction Spotlight Magazine, Issue 2, July 1992. Other sales followed. "The Man with Moon Hands" to New Mystery Magazine, Issue 3, December 1992 and the BIG ONE - a sale to Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine, Vol 101, #5, April 1993. Interesting note, this was a LaStanza story and like the novels, it had a profanity in dialogue. Editor Janet Hutchings missed it when she accepted the story and sent me a nice note asking if I could change one word in the story. Are you kidding? Hell, yes. I'm not a poet. I'm a writer. I'm not in love with words, they are only tools, so I switched to another tool. I'm proud of the story "Why" primarily because it dealt with a different kind of homicide we handled - suicide.

Which brings me to an important point. Listen to the editors of professional magazines, especially when they suggest a re-write. When editor Gardner Dozois at Asimov's suggested I re-work my story "Tyrannous and Strong," I resisted, then looked closely at his suggestions and rewrote the story, which appeared in Asimov's Science Fiction Magazine, Vol. 24, No. 2, February 2000. The story has been published five times, including magazines in Greece and Portugal.

In the 42 years since "The Sad Mermaid" saw print, I've had over 400 short story sales and received several thousand rejections as well as a SHAMUS AWARD for Best Private Eye Short Story and a DERRINGER AWARD for Best Novelette and other awards.

A highlight came with the January 1995 Issue of AMERICAN WAY: IN-FLIGHT MAGAZINE OF AMERICAN AIRLINES. Two pieces of fiction in the magazine. One of my stories and a short story by one of my literary icons - Ray Bradbury. The stories ran back to back in the 138-page slick magazine given free to American Airlines passengers that month. Ray Bradbury and I together.

When I was fifteen and dreaming of becoming a writer as I read THE MARTIAN CHRONICLES and THE GOLDEN APPLES OF THE SUN, I never dreamed I'd have a story in the same magazine with this man.

Now - If we can only answer the ultimate noir movie question - Why did Dick Powell keep get knocked out in movies?

That's all I got today -

www.oneildenoux.com

Michael Bracken's earlier post about his first published story inspired me to go back to my first stories.

My first story to see print was "The Sad Mermaid," a fantasy published in ELLIPSIS, student magazine of the University of New Orleans. Wasn't a sale. No payment. January, 1976. Another beginning writer had her first story printed in that issue of ELLIPSIS - fellow New Orleans mystery writer Tony Fennelly. In 1996, I made a little money on the story when it was published in TALE SPINNER Magazine, Issue 4.

Years of rejections of short stories followed. multi-genre failures. Decided to write a novel and finished GRIM REAPER (1988 Zebra Books). When it sold, I remember telling my father who asked, "They're paying you American money?"

Soon after, I met George Alec Effinger who was living quietly in the French Quarter. He took a look at my short stories and suggested I use the main character from my novel in stories.

First LaStanza story sold quickly -"The Desire Streetcar" Pulphouse Fiction Spotlight Magazine, Issue 2, July 1992. Other sales followed. "The Man with Moon Hands" to New Mystery Magazine, Issue 3, December 1992 and the BIG ONE - a sale to Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine, Vol 101, #5, April 1993. Interesting note, this was a LaStanza story and like the novels, it had a profanity in dialogue. Editor Janet Hutchings missed it when she accepted the story and sent me a nice note asking if I could change one word in the story. Are you kidding? Hell, yes. I'm not a poet. I'm a writer. I'm not in love with words, they are only tools, so I switched to another tool. I'm proud of the story "Why" primarily because it dealt with a different kind of homicide we handled - suicide.

Which brings me to an important point. Listen to the editors of professional magazines, especially when they suggest a re-write. When editor Gardner Dozois at Asimov's suggested I re-work my story "Tyrannous and Strong," I resisted, then looked closely at his suggestions and rewrote the story, which appeared in Asimov's Science Fiction Magazine, Vol. 24, No. 2, February 2000. The story has been published five times, including magazines in Greece and Portugal.

In the 42 years since "The Sad Mermaid" saw print, I've had over 400 short story sales and received several thousand rejections as well as a SHAMUS AWARD for Best Private Eye Short Story and a DERRINGER AWARD for Best Novelette and other awards.

A highlight came with the January 1995 Issue of AMERICAN WAY: IN-FLIGHT MAGAZINE OF AMERICAN AIRLINES. Two pieces of fiction in the magazine. One of my stories and a short story by one of my literary icons - Ray Bradbury. The stories ran back to back in the 138-page slick magazine given free to American Airlines passengers that month. Ray Bradbury and I together.

When I was fifteen and dreaming of becoming a writer as I read THE MARTIAN CHRONICLES and THE GOLDEN APPLES OF THE SUN, I never dreamed I'd have a story in the same magazine with this man.

Now - If we can only answer the ultimate noir movie question - Why did Dick Powell keep get knocked out in movies?

That's all I got today -

www.oneildenoux.com

15 February 2018

Older Than You Think

by Eve Fisher

"You, hear me! Give this fire to that old man. Pull the black worm off the bark and give it to the mother. And no spitting in the ashes!" - (Explanation later)The New York Times ran a great article the other day called, "Many Animals Can Count, Some Better Than You". I am sure that every one of us who has /had a pet can assure them of that. (Try to gyp a dog out of the correct number of treats.) Not only can they count - as a female frog literally counts the number of mating clucks of the male - but they can compare numbers. (Read about the guppies and the sticklebacks.)

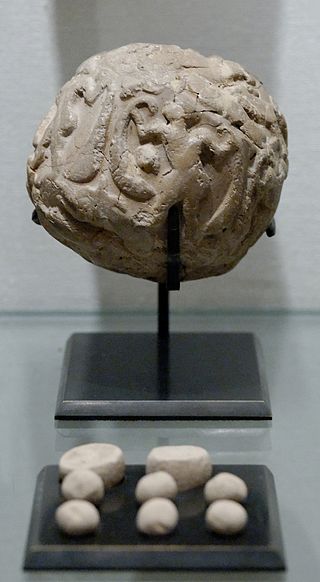

But where the article really got interesting was where they talked about that, despite math phobia, etc., humans have an innate "number sense." There is archaeological evidence suggesting that humans have been counting for at least 50,000 years. Before writing ever came around, people were using other ways of tallying numbers, from carving notches (bones, wood, stones) to clay tokens that lie all over Sumerian sites and which often looked, for decades, to archaeologists like bits of clay trash.

But where the article really got interesting was where they talked about that, despite math phobia, etc., humans have an innate "number sense." There is archaeological evidence suggesting that humans have been counting for at least 50,000 years. Before writing ever came around, people were using other ways of tallying numbers, from carving notches (bones, wood, stones) to clay tokens that lie all over Sumerian sites and which often looked, for decades, to archaeologists like bits of clay trash.But the ability to count and the desire to count and to keep track comes before tokens or notches, otherwise they'd never have bothered. And language - blessed language - comes before all of that. So get this: they say that the number words for small quantities — less than five — are not only strikingly similar across virtually every language in the world, but also are older (and more similar) than the words for mother, father, and body parts. Except certain words like... no, not that! (Get your mind out of the gutter) Except the words for the eye and the tongue. Make of that what you will...

Dr Mark Pagel, biologist at Reading University, said, “It’s not out of the question that you could have been wandering around 15,000 years ago and encountered a few of the last remaining Neanderthals, pointed to yourself and said, ‘one,’ and pointed to them and said, ‘three,’ and those words, in an odd, coarse way, would have been understood.” That just gave me goosebumps when I read it.

| Development of Sumerian cunieform writing, Td k at Wikipedia |

I admit, I'm fascinated by the past. (That's why I became a historian...) To me, history is time travel for pedestrians, a way to connect with our ancient ancestors. So let's zip around a bit, starting with jokes (Reuters):

|

| Sumerian man, looking slightly upset... (Wikipedia) |

“How do you entertain a bored pharaoh? You sail a boatload of young women dressed only in fishing nets down the Nile and urge the pharaoh to go catch a fish.” - Egypt, ca 1600 BC, supposedly about the randy Pharaoh Snofru

The earliest [written] "yo' mamma" joke, from an incomplete Babylonian fragment, ca 1500 BC:

"…your mother is by the one who has intercourse with her. What/who is it?"

(Okay, so it doesn't translate that well, but we all know where it's heading.)

And this riddle from 10th century Britain (for more see here):

"I am a wondrous creature for women in expectation, a service for neighbors. I harm none of the citizens except my slayer alone. My stem is erect, I stand up in bed, hairy somewhere down below. A very comely peasant’s daughter, dares sometimes, proud maiden, that she grips at me, attacks me in my redness, plunders my head, confines me in a stronghold, feels my encounter directly, woman with braided hair. Wet be that eye."

(Answer at the end and no peeking!)

Plot lines go very, very far back as well.

|

| Ancient Egyptian leather sandals (Wikipedia) |

The fairy tale with the oldest provenance is "The Smith and the Devil" which goes back at least 7,000 years, and has been mapped out over 35 Indo-European languages, and geographically from India to Scandinavia. (Curiosity) The bones of the story are that the Smith makes a deal with the Devil (or death) and cheats him. Now there's been all sorts of variations on it. In a very old one, the smith gains the power to weld any materials, then uses this power to stick the devil to an immovable object, allowing the smith to renege on the bargain. Over time, the smith's been transformed to clever peasants, wise simpletons, and, of course, fiddlers ("The Devil Went Down to Georgia" is, whether Charlie Daniels knew it or not, a variation on this very, very old fairy tale), and the devil occasionally got transformed to death or even a rich mean relative. Check out Grimm's "The Peasant and the Devil" and "Why the Sea is Salt".

|

| Enkidu, Gilgamesh's best friend - his death sends Gilgamesh in search of eternal life. (Urban at French Wikipedia) |

And, of course, many stock plots go at least as far back as Sumeria, including rival brothers (Cain and Abel), blood brothers (Gilgamesh and Enkidu), old men killing their rivals (Lamech, Genesis 4), the Garden of Eden, the Great Flood (complete with ark, dove, and rainbow), and the quest for eternal life (Gilgamesh).

BTW, most of the stories in Genesis come from the Epic of Gilgamesh, which makes perfect sense when you remember that Abraham is said to have come from Ur of the Chaldees, which was a Sumerian city.

BTW, most of the stories in Genesis come from the Epic of Gilgamesh, which makes perfect sense when you remember that Abraham is said to have come from Ur of the Chaldees, which was a Sumerian city.

But back to words, which are, after all, our stock in trade as writers. Remember above, where I quoted the NYT how you could communicate with Neanderthals by pointing and using number words? And remember that sentence at the very beginning?

"You, hear me! Give this fire to that old man. Pull the black worm off the bark and give it to the mother. And no spitting in the ashes!"

According to researchers, if you went back 15,000 years and said that sentence, slowly, perhaps trying various accents, in almost any language, to almost any hunter-gatherer tribe, anywhere, they'd understand most of it. You see, the words in that sentence are basic, almost integral to life, constantly used, constantly needed, for over 15,000 years, since the last Ice Age. (It's only recently that we've lost our interest in black worms except in tequila and mescal.)

Due to the fact that we live on a planet with 7.6 billion humans and counting, it's hard to realize that, back around 15,000, there were at most 15,000,000 humans on the entire planet (and perhaps as few as 1,000,000). They probably shared a language. If nothing else, they would have shared a basic trading language so that when they ran into each other, they could communicate. Linguistics says that most words are replaced every few thousand years, with a maximum survival of roughly 9,000 years. But 4 British researchers say they've found 23 words - what they call "ultra-conserved" words - that date all the way back to 13,000 BC.

Now there's a list of 200 words - the Swadesh list(s) - which are the core vocabulary of all languages. (Check them out here at Wikipedia.) These 200 words are cognates, words that have the same meaning and a similar sound in different languages:

So, what are they? What are these ultra-conserved words, 15,000 years old, and a window to a time of hunter-gatherers painting in Lascaux and trying to survive the end of the Younger Dryas (the next-to-the last mini-Ice Age; the last was in 1300-1850 AD)? Here you go:

There's got to be a story there. How about this?

Due to the fact that we live on a planet with 7.6 billion humans and counting, it's hard to realize that, back around 15,000, there were at most 15,000,000 humans on the entire planet (and perhaps as few as 1,000,000). They probably shared a language. If nothing else, they would have shared a basic trading language so that when they ran into each other, they could communicate. Linguistics says that most words are replaced every few thousand years, with a maximum survival of roughly 9,000 years. But 4 British researchers say they've found 23 words - what they call "ultra-conserved" words - that date all the way back to 13,000 BC.

|

| Speaking of 13,000 BC, here's a Lascaux Cave Painting. Wikipedia |

Now there's a list of 200 words - the Swadesh list(s) - which are the core vocabulary of all languages. (Check them out here at Wikipedia.) These 200 words are cognates, words that have the same meaning and a similar sound in different languages:

Father (English), padre (Italian), pere (French), pater (Latin) and pitar (Sanskrit).Now this makes sense, because English and Sanskrit are both part of the Indo-European language family. But our 23 ultra-conserved words are "proto-words" that exist in 4 or more language families, including Inuit-Yupik. (Thank you, Washington Post. And, if you want to wade through linguistic science, here's the original paper over at the National Academy of Sciences.)

So, what are they? What are these ultra-conserved words, 15,000 years old, and a window to a time of hunter-gatherers painting in Lascaux and trying to survive the end of the Younger Dryas (the next-to-the last mini-Ice Age; the last was in 1300-1850 AD)? Here you go:

thou, I, not, that, we, to give,

who, this, what, man/male,

ye, old, mother, to hear,

hand, fire, to pull, black,

to flow, bark, ashes, to spit, worm

There's got to be a story there. How about this?

"I give this fire to flow down the bark! Who pulls the man from the mother? Who pulls his hand from the fire? Who / what / we?"

I was trying a couple of variations on these words, and then I realized that the ultimate has already been done:

PS - the answer to the riddle is "onion".  |

"Who are you?" [said] the Worm.

Labels:

Alice in Wonderland,

Eve Fisher,

fairy tales,

Gilgamesh,

humor,

humour,

language,

Lewis Carroll,

linguistics,

riddles,

words

14 February 2018

The Iron River

Mexico has long fascinated us gringos, I think as a place of the imagination as much as a physical destination. The idea of Mexico is at least as strong with the Mexicans themselves, but more as a promise never kept. These days, Mexico in the grip of the narcotraficantes is far darker. "So far from God, so close to the United States," Porfirio Diaz once said. Easy to forget that it's a mirror image.

The simplest and most troubling schematic is the pipeline, The Iron River, drugs and human traffic moving north, money and guns moving south. What we're talking about is market share, access, gangster capitalism. Mexico has all the characteristics of a failed state. No rescue, no refuge. A phenomenon like the Juarez feminicidio, the unsolved murders of hundreds of women (a low estimate), doesn't take place in a vacuum. It has a context. I don't pretend to know all the reasons for it, but the drug traffic, and gang terrorism, is a fair guess as a contributor.

But for all its reptilian chill, we have to admit it makes marvelous theater. That's the contradiction. I look at the narcos, and I see predators, carrion-eaters, and maggots, the food chain as career path. Mara Salvatrucha? Looney Tunes. And the Zetas? Let's not even. On the other hand, you can't make these guys up. They're gonna crowd your peripheral. You want to take on the drug wars? This is the furniture. It's the threat environment. The picture's already been cast.

You set out to tell a cautionary tale, probably. Or almost certainly. It's the nature of things. T. Jefferson Parker, in the Charlie Hood novels. Iron River, The Border Lords, The Famous and the Dead, to name his most recent three. Two by Don Winslow. The Power of the Dog and The Cartel. And the stories I've written myself about the border war. Doc Hundsacker, the Texas Ranger working out of El Paso, and Doc's pal Fidelio Arenal, the Federale major across the river in Juarez. Pete Montoya, the state cop based in Santa Fe, and Albuquerque FBI agent Sandy Bevilacquia. They're real to me, their strengths and weaknesses, and the consequences of what they choose to do. Not my sense of duty, or my moral choices, but theirs.

I'm not beating a drum, or selling a cure for cancer, or telling you how to vote. I'm saying that if you decide you're telling a certain kind of story, you may very well have to choose up sides. In fact, the story will probably pick a side for you. They do that, damn it. You wind up on the side of the angels, when you were ready to sell your soul to the Devil. Cheap at twice the price.