On Monday, B.K. Stevens—an award-winning mystery writer, a member of the SleuthSayers family here, and a great friend to so many of us—died in Virginia. As her husband Dennis explained in phone calls and emails with me and then on Facebook, Bonnie collapsed at their home on the previous Wednesday night and was taken to the hospital; she was unresponsive and did not regain consciousness. Her death is a loss that's already been felt strongly not just here among her peers at SleuthSayers but throughout the larger mystery community, where she was admired not just as a writer but also as a person, full of wit, wisdom, and generosity. She was one of my own best friends in the mystery world, and all of this is simply a heartbreak.

Bonnie and I first crossed paths back in 2011, when each of us won Derringer Awards—Bonnie in the Long Story category for her story "Interpretation of Murder," originally published in Alfred Hitchcock's Mystery Magazine and centered on American Sign Language interpreter Jane Ciardi, and me in the Novelette category. Bonnie was already enjoying a remarkable career at that point—she published more than 50 short stories in all, most of them for AHMM, and many of them part of three long-running series, featuring respectively Leah Abrams, Iphigenia Woodhouse, and Walt Johnson & Gordon Bolt. You can read stories from the first two series in Bonnie's outstanding collection Her Infinite Variety: Tales of Women and Crime (Wildside Press), and you can get her own in-depth reflections on all her work—and insights into the woman behind that work—in an extensive and illuminating interview in the latest issue of The Digest Enthusiast from Larque Press.

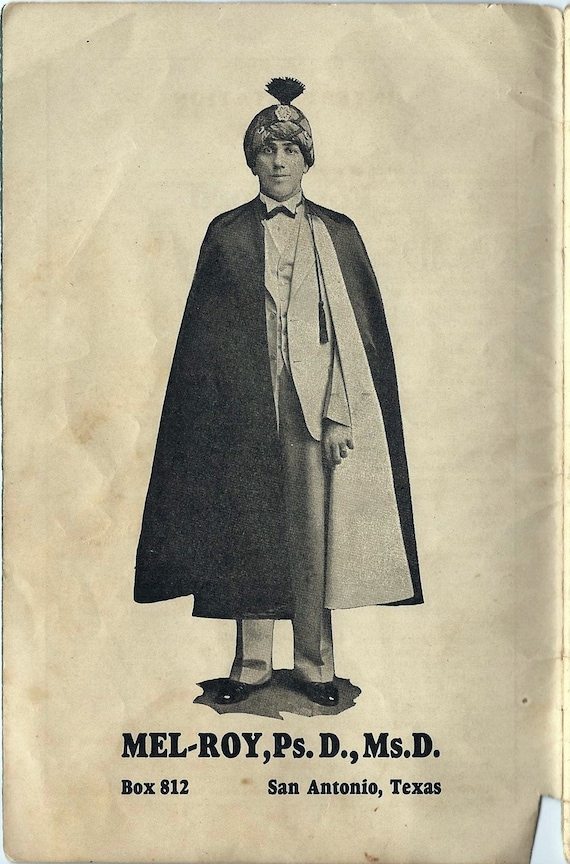

|

| Bonnie and her daughter Sarah Gershone, an ASL interpreter, with Interpretation of Murder at Malice Domestic |

It's not just coincidence, though, that drew Bonnie and me together, but a more fundamental commonality of belief about how short fiction should work. As she and I served on panels together at Malice Domestic or even talking more casually at Bouchercon or the Virginia Festival of the Book or while sharing a table at the Suffolk Mystery Authors Festival, I found myself struck by and honestly thrilled by how often Bonnie's thoughts about crime fiction and short stories meshed with my own and by her gift for articulating those thoughts in ways that made them so much clearer to me; she came back time and again, for example, to Poe's essay on the single-effect in short fiction—a cornerstone for both of us about the art of composition—and she spoke about it with the grace of the professor that she was for so many years. More recently, Bonnie and I had back-to-back essays on our fiction in the "First Two Pages" blog she hosted (more on that in a moment), and we both commented on how our thoughts on the beginnings of stories echoed one another—on slow beginnings, in fact, and our faith that readers would stick with them, contrary to conventional wisdom about starting quickly. The story Bonnie wrote about, "The Last Blue Glass" (originally published in AHMM and linked here), was an Agatha finalist this year and is currently in contention for the Anthony Award for Best Novella, and you can read her essay on the story's first two pages here. As often with Bonnie, as much as I enjoyed her fiction in its own right, that joy and pleasure was always enhanced by hearing her talk about the process of writing the stories—thoughts on prose and plot and structure and more that served as evidence of her superior approach to the craft of writing.

As regular readers of SleuthSayers know, her posts here were carefully considered essays on that craft as well—analyzing stories with a keen eye or explaining in comprehensive detail some fundamental approaches to crime fiction that any writer could learn from, opening perspectives for all of us time and again; just check out her essay from last fall about "Camouflaging Clues" or another on "Whodunits: Pet Peeves" or her analysis of "The Twist" in one of O. Henry's most famous tales. Perhaps more than all of them, her essay "Sayers vs. Aristotle: What's So Funny?" surely proves that Bonnie was as brilliant an essayist and critic as she was a fiction writer.

Beyond sharing her perspectives and her wisdom in posts like those, Bonnie was generous to writers in other ways. I mentioned her blog above, "The First Two Pages," where each Tuesday Bonnie hosted a writer of novels or short stories to explain "how he or she faced the challenges of those brutally difficult—and vitally important—first two pages." These weekly posts offer great insights into craft but also gave Bonnie a chance to turn attention toward other writers throughout our community, give them opportunities to reach more readers and find new fans. And as you'll hear below, Bonnie was also quick to reach out to fellow writers with congratulations or support, celebrating the larger community always.

Bonnie was generous to me as well—sometimes in small ways, but aren't those often the ones that count the most? Bonnie and I both enjoyed a good bourbon, a Manhattan in particular in her case, and I'll always remember waiting for our flights in the Albany airport after Bouchercon, and Bonnie and Dennis buying a round of drinks for us, the three of us chatting while we waited. At other conventions, we always made a point to find time together, often with Dennis and Bonnie hosting again (there may be no better hosts), and there in person or later in emails, we always found more points of common interest: our shared admiration of Dorothy Sayers' Gaudy Night as one of the true masterpieces of mystery, for example, or our love of Harry Kemelman's Rabbi Small novels. Over time, Bonnie and I began talking about funneling our shared interests into plans for collaborating on a major project, one that was ongoing and even ramping up when she died; in fact, I have two emails from Bonnie in my inbox now, one about that collaboration and another continuing our prep for a workshop we were scheduled to co-present at last weekend's Suffolk Mystery Authors Festival.

"All things considered, I think our plans are coming together well," Bonnie wrote to me on that Wednesday morning, and I left a voicemail for her early the next morning to talk in particular about those final touches to the Suffolk workshop. When the return call came, I picked up the phone, enthusiastic to chat, looking forward to the weekend—but it was Dennis on the line instead, bringing the first round of troubling news.

There is much to say here, of course, about the swiftness of time and the poignancy of regrets and the emptiness of plans undone and promises unfulfilled. But instead let me simply say this again: Both professionally and personally, Bonnie Stevens was one of my dearest friends, and her death is sudden and sharply felt—a loss to all of us in the mystery community. I will miss her in so very many ways.

In the parlance of obituaries, Bonnie is survived by her husband Dennis Stevens and their daughters Sarah Gershone and Rachel Stevens, and our condolences and good wishes go out to all of them and to Bonnie and Dennis's grandchildren as well. But Bonnie is also survived by an outstanding body of work that will surely continue to give readers joy and pleasure in the years to come—and give us writers, now and in the future, models of excellence by which to measure our own work, models to aspire toward ourselves.

I asked several friends of Bonnie's in the mystery community to share a few of their own thoughts and memories, and I'm glad to welcome them here now.

LINDA LANDRIGAN, EDITOR, ALFRED HITCHCOCK’S MYSTERY MAGAZINE

Discovering a new story from Bonnie over the transom was always a thrill. She was a writer’s writer. Her stories are well conceived, well written, and well plotted, but for me her great skill was in character. Even those that were comic were always drawn with enormous sympathy and warmth. In addition to the mystery, each story was always firmly rooted in the relations between characters. I always felt that her skill with characters was a reflection of her empathetic, articulate, and engaged personality. Hers was an influential voice in AHMM’s pages for nearly 30 years.

CARLA COUPE, WILDSIDE PRESS

As I’m sure many others will attest, Bonnie was a lovely person—generous with her time and with a kind word for all. When she and I worked together on her collection of short stories, Her Infinite Variety: Tales of Women and Crime, her perception and intelligence came to the fore. Each story displays her mastery of the form, as well as her insight into what makes a compelling character and intriguing plot. Her introductions to her various series show her firm grounding in the history of the genre, and her comments on each story shed light on its genesis and development. She unselfishly shared her knowledge and talent with so many, and despite her untimely death, her legacy will continue.

MEG OPPERMAN

Bonnie was an exceptional short story writer, and an even better human being. When I was nominated for a Derringer, she was one of the first people to send me congratulations. It meant the world to me because she is one of my absolute favorite short story writers. She could take a seemingly simple setup and turn it into a gripping tale. But more than even her stories, I recall a time she said a few well-placed words when I was feeling particularly frustrated and downtrodden about my own work. I doubt she would even remember her kindness that day, but I sure do. She embodied the idea of "paying it forward." My life is richer for having met her and read her work. She will be missed.

DEBRA GOLDSTEIN

Bonnie and I became listserv acquaintances in 2014, but our true friendship began in January 2015 when, while reading back issues of Alfred Hitchcock Mystery Magazine, I came across her short story, “Thea’s First Husband.” I didn’t know it had been nominated for Macavity and Agatha awards, only that it moved me in a way few stories, other than Shirley Jackson’s “The Lottery,” had. As a bottom of the heap short story writer, I recognized I was reading how a master interweaves plot, dialogue, and setting to escalate tension and intrigue a reader. I wrote Bonnie a fan e-mail telling her this and asking if she ever taught classes. I told her I had had some success with having stories and two novels accepted, but hadn’t had the guts to try for AHMM or EQMM, but reading her story moved me and I hoped there was a way I could learn from her.

She replied with joy that her writing had touched me, but told me she was a retired English professor who didn’t teach online classes. Bonnie then gave me a one-paragraph summary of things I should read. I read those things and also her novels, Interpretation of Murder and Fighting Chance, and the collection of eight AHMM short stories, Her Infinite Variety: Tales of Women and Crime. The comments between the stories tell a tale of Bonnie as a writer in themselves. We met a few months later at Bouchercon Raleigh and began a tradition of sharing a planned dinner or drinks at any conference we both attended. We also posted blogs for each other, exchanged congratulatory emails, discussed writing and writing opportunities, and talked family.

Bonnie’s Jewish faith and family traditions with her husband, Dennis, daughters Sarah and Rachel, and grandchildren were even more of a passion than her writing. Her Facebook posts were filled with the accomplishments of her grandchildren and her love for her family. Behind the scenes, this year, we compared our joy at having our first grandchild bar/bat mitzvahed and kidded we should introduce her single daughter to my unmarried son. Such a match. Bonnie and I could be related!

There won’t be any more dinners or talk of introducing our children, but what I will remember is a package I received a week after Malice 2017. It contained a note and five copies of the May/June 2017 issue of Alfred Hitchcock Mystery Magazine that Bonnie and Dennis took the time to collect from their registration bags and the giveaway room. The note told me she knew I would want extra copies of this issue because had my name on the cover and contained my first AHMM story, “The Night They Burned Ms. Dixie’s Place.” She thought it was an award-winning story. Who knows if it will be nominated for anything at the 2018 events at which it is eligible, but I saved the note. With Bonnie and others guiding me, I’ve already won the biggest award in my book—Bonnie’s approval.

PAULA BENSON

I met Bonnie Stevens through her writing. I’ll never forget reading “Thea’s First Husband,” and thinking it was the most brilliantly written story. So, like any avid fan, I wrote her a letter. And, she answered, graciously and humbly. She invited me to join her at her Malice Domestic banquet table when the story was nominated for an Agatha. That’s how I met her husband Dennis. If ever two people were meant to be together, Bonnie and Dennis Stevens were that couple. Some of my happiest memories are of seeing Bonnie and Dennis approach me at writing conferences, her arm in his, perfectly content.

Bonnie brought so much of herself, both in skill and experience, to her writing. She also learned from her family and incorporated their knowledge into her stories and novels. Her protagonist Jane Ciardi, a sign language interpreter, in her short story “Silent Witness” [originally "Interpretation of Murder"] and her novel Interpretation of Murder, was based somewhat on her daughter Sarah Gershone’s skill. For Author’s Alley at Malice Domestic one year, Bonnie and Sarah appeared together, demonstrating American Sign Language for the audience. For her YA novel, Fighting Chance, Bonnie collaborated with Dennis, a martial arts expert, to choreograph the scenes accurately. She delighted us all in describing how she and Dennis “practiced” the moves.

Dennis and daughters Sarah and Rachel were Bonnie’s greatest supporters. When she received the contract from Black Opal Books for Interpretation of Murder, they gave her some very special gifts which she featured on her Facebook page: a black opal necklace from Dennis and a personalized cutting board. Somehow, the girls thought it appropriate for a mystery writer to be celebrated with a surface that would see a lot of action from knives. Both gifts delighted Bonnie.

My first Malice panel included Bonnie. She was so incredibly kind and helpful, putting me at ease and encouraging me. Her support for me and others was demonstrated in so many ways. She sent a message welcoming every new group of Guppies and many notes of congratulations.

While I will continue to treasure her stories, I will cherish the times we spent together and the emails she sent me. She was a master of the craft, yet talked to me as if I were an equal. Her belief in me is a tremendous, sustaining gift. I am so very grateful for our friendship.

BARB GOFFMAN

I’ve known Bonnie for more than a decade. We always talked about getting together for a meal at the next Malice Domestic, but somehow, we never found the time. It’s something I truly regret.

I spent tonight reading through old emails from Bonnie. She was so supportive and gracious, as well as well-prepared and thoughtful. Back when I was program chair of Malice Domestic, I always tapped Bonnie to be a moderator because I knew she’d do a bang-up job. She approached the job of a panel moderator analytically, reading her panelists’ books and coming up with excellent questions that made the panels interesting and helped showcase her authors and their books.

Incidentally, that’s the same way she approached her writing, analytically and thoroughly. She once said she would write perhaps thirty pages of notes before she started writing a story. The notes sometimes were way longer than the story ended up being. It’s a process what worked wonders for her, as her many award nominations can attest, as well as her Derringer win.

Bonnie also had a wry side and a delightful way with words. I came across one email in which she described some connecting flights she’d taken right before catching the flu. She said, “the planes were packed so tightly that it was positively claustrophobic, and I'm sure germs of every sort were making lots of new friends.”

Bonnie wrote a lot of great stories, including “The Last Blue Glass,” currently and deservedly up for the Anthony Award for Best Novella. But the story of hers that stands out in my mind most is one that never got published, at least not traditionally. Bonnie wrote a story about an old dog, based in part on her old dog, Alex, and she put it on her website. In the story, Alex had physical problems, as old dogs are apt to do, which resulted in some less-desirable behaviors, including defecating in the house. Bonnie wrote to me that some dog-less friends who read it wondered if anyone would really put up with such behavior, but Bonnie knew full well that they would, because she herself did. She said, “We really did put up with the real Alex's bad habits, for a couple of years, until the night his heart gave out and he died in our arms; nothing would have made us happier than putting up with his habits for many, many more years.”

That was Bonnie. Full of love and heart and graciousness. I wish we could have put up with her for many, many more years to come. She will be missed.

.jpg/220px-MotherNight(Vonnegut).jpg)