Those of you who follow my posts on SleuthSayers know I have a low opinion of Edward Snowden, the NSA leaker, but you may be surprised that my take on Bradley Manning is quite different. (Two other high-profile courts-martial rendered verdicts this past week, but the three cases have little to do with each other.)

The first question is what Manning did. Essentially, he delivered a core dump of classified materials to WikiLeaks. Two questions follow on the first. 1) Did he compromise sources and methods? Without a doubt. 2) Did he put the lives of soldiers in combat at risk? The answer appears to be more or less no, but it's a hedged bet.

The most serious offense he was charged with was Aiding the Enemy, but the trial judge acquitted. He was found guilty of violating the Espionage Act, and drew a thirty-five-year sentence, convicted on twenty counts, in all.

People unfamiliar with the UCMJ---the Universal Code of Military Justice---don't realize how inflexible it is, by design. Its obvious purpose is to enforce discipline in the ranks, both officers and enlisted. But it guarantees equal treatment, and protects the rights of the accused. In other words, the UCMJ is meant to guard against the imposition of arbitrary punishment. You can no longer be flogged for minor infractions, on the word of your captain alone, as was the rule during the Age of Sail. The power of the officers over you is structured, and not a matter of their personal whim. This is known formally as Chain of Command. Are there abuses of the system? Of course. The military is a hierarchal organization, with the strengths and weaknesses that entails, and highly formal. Duty is an obligation, freely chosen, but not a bargaining chip.

My own experience of the UCMJ was an Article 15, for Failure to Repair, and it cost me a loss in rank I had to claw back. To explain the vocabulary: an Article 15 is non-judicial punishment, administered by your commanding officer; Failure to Repair means not reporting to a required formation, which is a slap on the wrist compared to Dereliction of Duty; and, for the record, I admitted my guilt. In cases like this, the commanding officer has a certain amount of latitude, and can impose a fine, or reduction in rank, and even revoke your security clearance, but you won't go to jail. That takes a court-martial.

What does this have to do with Manning? For one thing, my job was much the same as his, battlefield analysis, even if my war was cold (the Russians and the Warsaw Pact) and his was hot. We worked under similar restrictions, and had access to secure documents and databases. Both of us, presumably, understood the consequences of the unauthorized release of restricted materials. In fact, it remains an article of faith among almost everybody I know who's worked in the spook trade that your lips are forever sealed.

Much has been made of Manning's unsuitability for the military, generally, and more specifically for his job description, handling sensitive stuff. Given his behavior patterns, he should have had his clearance pulled, and been relieved. Why didn't this happen? Because they needed warm bodies, and as manifestly unfit for duty as Manning so obviously was, they kept him at this station. The kid was desperately out of his element. His gender-identity issues have surfaced since, but even at the time, he was trapped in a hostile workplace environment, and almost certainly bullied. He was queer in the old-fashioned sense, meaning the odd guy out, an easy target for ridicule. The larger point is, that he tried going through channels. He made his unhappiness known, and although his First Sergeant did try to help him find his feet, nobody bit the bullet and recommended his immediate discharge, not only for Manning's own good, but for the success of the overall mission.

This isn't to excuse, in any way, Manning's criminal acts. He violated basic military discipline, and he broke the cardinal rule of the intelligence world. (The question of whether his airing those secrets on the Internet serves some greater good is moot, or at least not the purpose of this post. In the event, I don't buy that defense.) My real disappointment isn't with Manning, anyway. What's instructive about this whole, sorry enterprise is that the chain of command failed a soldier. Square peg in a round hole, Manning was still one of their own, and they betrayed his trust. There's more than enough guilt to go around.

28 August 2013

27 August 2013

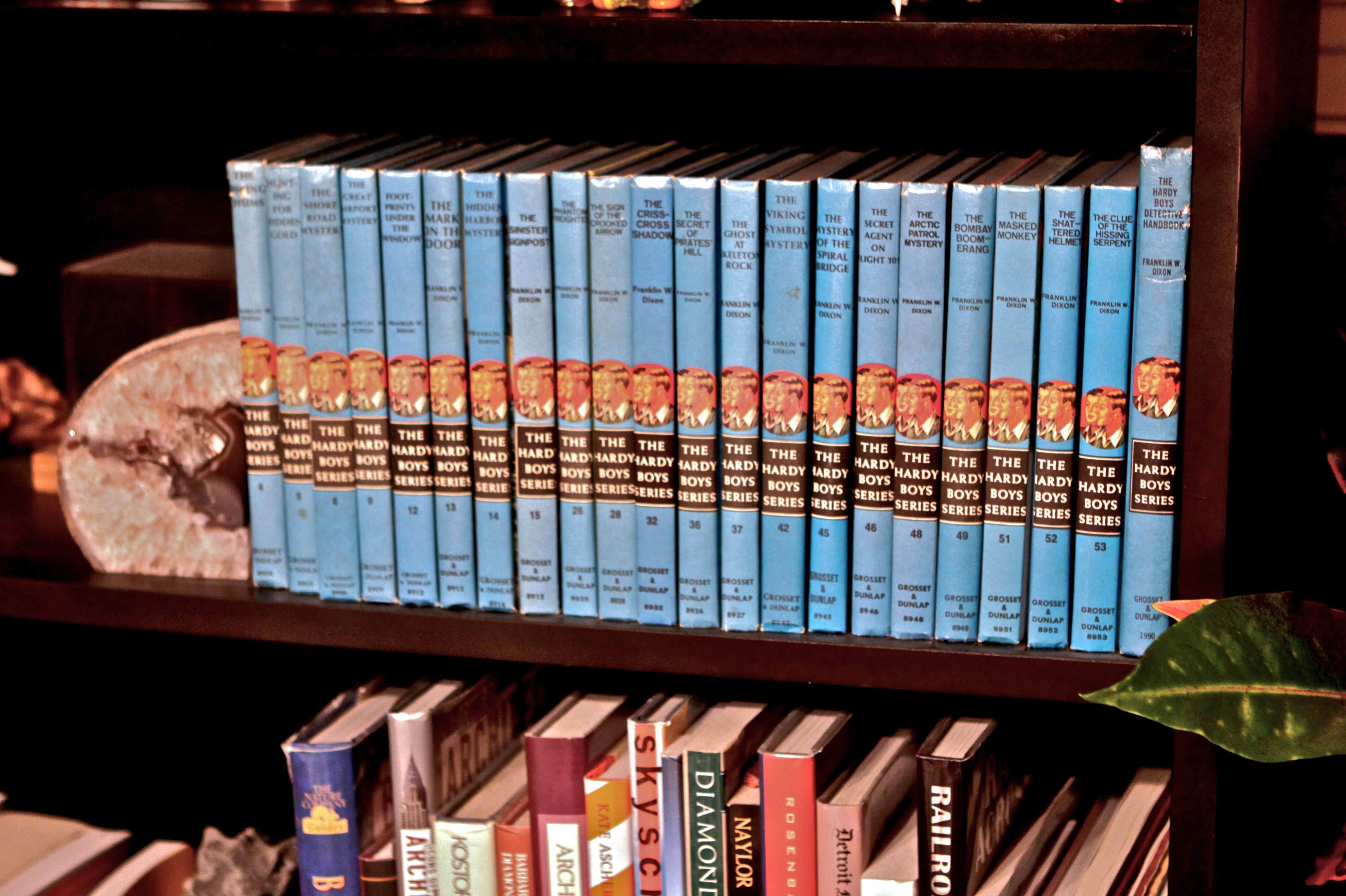

The Hardy Boys Mystery

by Dale Andrews

I was so awed by Disney’s television adaptation of the first Hardy Boys mystery, originally published as The Tower Treasure, that I immediately went out in search of Hardy Boys books that I could devour on my own.

Naturally, the first place I tried was the library. But when I summoned up the courage to ask the librarian where I might find the library's collection of Hardy Boy books she looked aghast. Her eyes widened, she snorted and then, looking down over the tops of those half spectacles, informed me that the Hardy Boys series was simply not the sort of book that one found in a library.

This was astonishing to me at seven. Why would the library refuse to stock an entire series of books? Particularly a popular series written for kids? But no matter. I was on a mission. I persevered.

This was astonishing to me at seven. Why would the library refuse to stock an entire series of books? Particularly a popular series written for kids? But no matter. I was on a mission. I persevered.

|

| Stix, Baer and Fuller, Clayton Missouri circa 1956 "Second floor, Books." |

The neighborhood bookstore also did not carry the Hardy Boys, and I sensed in them, too, a degree of disdain when I asked about the books. But this was the 1950s, a time when department stores were truly stores with departments. So the next time I went shopping with my parents at the neighborhood Stix, Baer and Fuller department store (a St. Louis fixture back then) I headed straight for the book department. And there they were. Row after row of hardcover Hardy Boy mysteries, each for sale for $1.00. I immediately purchased the first three books in the series, exhausting my saved allowance funds, even though my mother warned me that, at age 7, I probably would have an extremely difficult time reading them.

I didn't. As soon as we got home I wedged myself into the corner of the living room sofa and was lost in the marvelous adventures of Frank and Joe Hardy. I think that it was those books that really taught me the joy of reading for pleasure.

For the next several years Hardy Boy mysteries topped every one of my birthday and Christmas wish lists. But as I got deeper into the series things began to bother me. How could Frank and Joe remain, respectively, 16 and 15 years old in each mystery? And who was this “Franklin W. Dixon” who had written the marvelous series, beginning way back in the 1920s?

As time passed, like every other fan of the Hardy Boys, I began to grow up. My taste for mysteries had been whetted and more and more my collection of Hardy Boy books sat gathering dust on the bottom shelf of the bookcase as I turned to Arthur Conan Doyle, Ellery Queen and others. But I never forgot about Frank and Joe, and if asked, I would readily volunteer that my thirst for detective fiction, in fact my appetite for reading fiction, began with, and was fueled by, their exploits.

If the theme of my last article, on pseudonyms, was John Steinbeck’s admonition that “we can’t start over,” the theme of this one must be Thomas Wolfe’s “you can’t go home again.”

Have any of you tried to go back, as adults, and re-read a Hardy Boys book? Or a Nancy Drew mystery? It is only when I attempted this myself that I finally understood the librarian's aghast look as she stared down at me over her half specs when I was seven. No two ways about it, the Hardy Boys are repositories of atrocious writing.

Back in 1998 Gene Weingarten, staff writer for The Washington Post (and a very funny man) reached the same conclusion in a wonderful article chronicling his own adult-rediscovery of the works of Franklin W. Dixon:

Now, through my bifocals, I again confronted The Missing Chums [which is the fourth volume of the series]. Here is how it begins:

"You certainly ought to have a dandy trip."

"I'll say we will, Frank! We sure wish you could come along!"

Frank Hardy grinned ruefully and shook his head. . . .

"Just think of it!" said Chet Morton, the other speaker. "A whole week motorboating along the coast. We're the lucky boys, eh Biff?"

"You bet we're lucky!"

"It won't be the same without the Hardy Boys," returned Chet.

Dispiritedly, I leafed through other volumes. They all read the same. The dialogue is as wooden as an Eberhard Faber, the characters as thin as a sneer, the plots as forced as a laugh at the boss's joke, the style as overwrought as this sentence. Adjectives are flogged to within an inch of their lives: "Frank was electrified with astonishment." Drama is milked dry, until the teat is sore and bleeding: "The Hardy boys were tense with a realization of their peril." Seventeen words seldom suffice when 71 will do:

"Mrs. Hardy viewed their passion for detective work with considerable apprehension, preferring that they plan to go to a university and direct their energies toward entering one of the professions; but the success of the lads had been so marked in the cases on which they had been engaged that she had by now almost resigned herself to seeing them destined for careers as private detectives when they should grow older."

Physical descriptions are so perfunctory that the characters practically disappear. In 15 volumes we learn little more than this about 16-year-old Frank: He is dark-haired. And this about 15-year-old Joe: He is blond.

These may be the worst books ever written.

Gene Weingarten captures perfectly the surprise and disappointment that a returning reader encounters when cherished childhood memories are found to have been premised not on greatness but on hack mediocrity. His reaction (and my own) to discovering, as an adult, the shortcomings of the mystery series we loved as children is not uncommon. It is, in fact, almost universal among those who attempt to “go home again” to those Franklin W. Dixon volumes that highlighted our childhood.

When Benjamin Hoff, bestselling author of The Tao of Pooh re-read the Hardy Boys as an adult he felt compelled, like Pygmalion, to try to set things right. Mr. Hoff went so far as to re-write the second book in the series, The House on the Cliff and published his re-imagined story, re-titled The House on the Point, complete with two appended essays analyzing the original Franklin W. Dixon work. A noble attempt to re-build that childhood home that he had returned to only to find in shambles.

But ultimately you can’t do it. Here is what Austin Chronicle reviewer Tim Walker wrote of Hoff’s futile attempt:

But ultimately you can’t do it. Here is what Austin Chronicle reviewer Tim Walker wrote of Hoff’s futile attempt:

Benjamin Hoff's loving tribute to his boyhood heroes the Hardy Boys recalls The House on the Cliff, the second installment of the original series. As one would hope, Hoff's book is executed with a literary sensibility far superior to the original's. While the narrative seldom attains the gentle flow of Hoff's The Tao of Pooh, its many historical and physical details lend fine verisimilitude, and Hoff has drawn its characters with a real human depth that is absent from the stories that have been selling strongly for 75 years.

[But] any Hardy Boys tribute will run up against the thorny fact of the originals' bad writing. The plots make little sense, the wooden dialogue is in some way an improvement on the cardboard-cutout characters, and the boys themselves take on lethal dangers with barely a second thought in an otherwise sober setting that doesn't make the fantasy element of the book clear. . . . Hoff's book is worth reading, but if it fires you up to re-read the Hardy Boys, understand that you'll be doing it only for nostalgia.

|

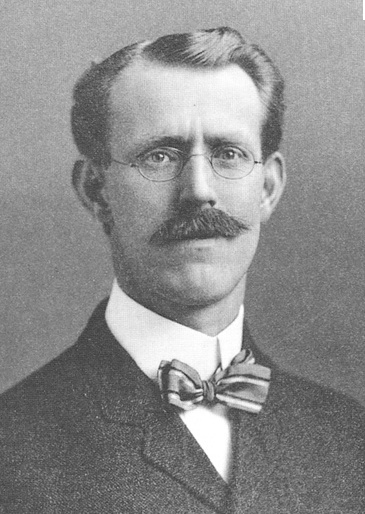

| Edward Stratemeyer |

So. Who was this Franklin W. Dixon, and how could he have produced such a popular but, at base, awful series of books? The answer to that question is pretty much common knowledge now.

In fact, there never was a “Franklin W. Dixon.” The name is a pseudonym utilized by a number of contract writers who produced the Hardy Boys series and the Nancy Drew series ("written" by the equally fictional Carolyn Keene), for the Stratemeyer Syndicate, a self-proclaimed “packager’ of books established in 1905 to provide reading material for young adults (and to make money along the way). The syndicate was the brainchild of Edward Stratemeyer, who wrote the first Bobbsey Twin book before realizing that producing series of childrens’ books under different pseudonyms, ghostwritten by hired writers, would play better in the marketplace. This assumption proved entirely correct. By 1930, the Stratemeyer Syndicate had sold over 5 million copies of its ghosted books and basically controlled the U.S. market for childrens’ books.

In fact, there never was a “Franklin W. Dixon.” The name is a pseudonym utilized by a number of contract writers who produced the Hardy Boys series and the Nancy Drew series ("written" by the equally fictional Carolyn Keene), for the Stratemeyer Syndicate, a self-proclaimed “packager’ of books established in 1905 to provide reading material for young adults (and to make money along the way). The syndicate was the brainchild of Edward Stratemeyer, who wrote the first Bobbsey Twin book before realizing that producing series of childrens’ books under different pseudonyms, ghostwritten by hired writers, would play better in the marketplace. This assumption proved entirely correct. By 1930, the Stratemeyer Syndicate had sold over 5 million copies of its ghosted books and basically controlled the U.S. market for childrens’ books.

One of Stratemeyer’s greatest successes was the Hardy Boys. The original series consisted of 58 installments, and was followed by several related series, re-imagining Frank and Joe in more modern times. The latest, The Hardy Boys Adventures, was launched in 2013, and new volumes are currently being published in that series. From the date of the original publication of The Tower Treasure in 1927 there has never been a year when the Hardy Boys series was out of print.

|

| Leslie McFarlane |

McFarlane, like all subsequent Hardy Boys authors, toiled in secrecy in return for a pittance. He was required to sign a confidentiality agreement obligating him never to divulge his authorship of Franklin W. Dixon books. In return he, and the later writers, were paid “princely” sums ranging from $75.00 to $100 per book in the early years to produce new installments in the series, each rigidly premised on outlines supplied by the Stratemeyer Syndicate. The Bobbsey Twins, Nancy Drew and Tom Swift series were all written under the same arrangements. Attempts by McFarlane and subsequent authors to vary from the script, or to breathe life into the characters reportedly were dealt with quickly and ruthlessly by the editorial pens of the syndicate.

Did all of this grate on McFarlane? You bet. Gene Weingarten’s article collects and analyzes entries from the detailed diaries that McFarlane kept over the years.

Did all of this grate on McFarlane? You bet. Gene Weingarten’s article collects and analyzes entries from the detailed diaries that McFarlane kept over the years.

“The Hardy Boys" [series] is seldom mentioned by name [in McFarlane’s diaries], as though he cannot bear to speak it aloud. He calls the books "the juveniles." At the time McFarlane was living in northern Ontario with a wife and infant children, attempting to make a living as a freelance fiction writer.

Nov. 12, 1932: "Not a nickel in the world and nothing in sight. Am simply desperate with anxiety. . . . What's to become of us this winter? I don't know. It looks black."

Jan. 23, 1933: "Worked at the juvenile book. The plot is so ridiculous that I am constantly held up trying to work a little logic into it. Even fairy tales should be logical."

Jan. 26, 1933: "Whacked away at the accursed book."

June 9, 1933: "Tried to get at the juvenile again today but the ghastly job appalls me."

Jan. 26, 1934: "Stratemeyer sent along the advance so I was able to pay part of the grocery bill and get a load of dry wood."

Finally: "Stratemeyer wants me to do another book. . . . I always said I would never do another of the cursed things but the offer always comes when we need cash. I said I would do it but asked for more than $85, a disgraceful price for 45,000 words."

He got no raise.

McFarlane eventually gritted his teeth and abandoned the series when he realized that the pressures of grinding out new installments had driven him to alcoholism. After shaking that addiction at a treatment center McFarlane never wrote another Hardy Boys book and instead went on to a relatively successful career as a novelist and screenwriter. But the ghosts of Frank and Joe continued to haunt him. Reportedly when McFarlane was near death in 1977 he would awaken from a diabetic coma screaming, having hallucinated that upon his death he would only be remembered for writing the Hardy Boys.

So, what's the take away here? Were we all just wrong as kids? And what about the fact that after reading the Hardy Boys, or the "sister" Nancy Drew series, most of us went on, and graduated to better books, doing so with an instilled love of reading, and of mysteries?

A funny thing about trying to re-live parts of one’s childhood. Through an adult’s eyes things just don’t look the same. Returning to our earliest literary loves can be as unpalatable as returning to Gerber's baby food. If you try this anyway (the literature, not the baby food), be prepared for some disappointment, or worse. But at the same time remember that what we saw, and did, as children, and what inspired and molded us, made us what we are today. No matter how bad those Hardy Boy books may be when viewed through adult eyes -- our own now, or that aghast librarian’s I encountered in 1956 -- Frank and Joe (and Nancy Drew) for many of us provided that initial flame, the catalyst that ignited a lifelong interest in mystery fiction.

So, well done, Franklin W. Dixon (and everyone behind his curtain). Poorly written, but still, in the end, well done!

So, well done, Franklin W. Dixon (and everyone behind his curtain). Poorly written, but still, in the end, well done!

Labels:

Dale C. Andrews,

Edward Stratemeyer,

Franklin W. Dixon,

Hardy Boys,

Leslie McFarlane,

Mickey Mouse Club

Location:

Chevy Chase, Washington, DC

25 August 2013

The Dissidents

by Louis A. Willis

From the introduction: Certainly one of the aspects that made putting this collection together so cool for us as editors and contributors was our respective backgrounds in activism and community organizing. The lessons we took away from those experiences were not only about the need for a incisive power analysis and being aware that goals and objectives have to be constantly readjusted, but just how indomitable are the spirits of everyday working people, be they dealing with faceless slumlords, police abuse, rights on the shop floor or simply banding together to get a stop light erected at a street corner for their kids.

From the introduction: Certainly one of the aspects that made putting this collection together so cool for us as editors and contributors was our respective backgrounds in activism and community organizing. The lessons we took away from those experiences were not only about the need for a incisive power analysis and being aware that goals and objectives have to be constantly readjusted, but just how indomitable are the spirits of everyday working people, be they dealing with faceless slumlords, police abuse, rights on the shop floor or simply banding together to get a stop light erected at a street corner for their kids.

I’m reading my way through the many anthologies on my bookshelves, but not in any systematic way. I usually pick an anthology based on catchiness of the title. With Send My Love And A Molotov Cocktail: Stories of Crime, Love and Rebellion, I thought about how the versatile crime and mystery genre is often used to tackle social issues. These days I read fiction for pure enjoyment not profound insights on the human condition. So, as I began reading, I had to keep an open mind and not judge the stories based on the authors’ opinions toward the social issues. I chose three stories for this post based not on the issues but on the authors.

I chose “Bizco’s Memories” by Paco Ignacio Taibo II because I need to read more stories by foreign authors, especially those south of the border. “Bizco’s Memories” is a framed story about how political prisoners are treated more harshly than common prisoners in Mexico. As I read, I thought about the SleuthSayer posts on narrative voice. In framed stories there are, of course, two voices. In this one, the inside voice, Bizco, an unreliable narrator, tells a story to the outside voice of how the political prisoners exacted revenge on the common prisoners who had been harassing them. Bizco doesn’t end the story but merely stops talking. I sensed another voice or style, that of the translator and editor, Andrea Gibbons.

I chose “Bizco’s Memories” by Paco Ignacio Taibo II because I need to read more stories by foreign authors, especially those south of the border. “Bizco’s Memories” is a framed story about how political prisoners are treated more harshly than common prisoners in Mexico. As I read, I thought about the SleuthSayer posts on narrative voice. In framed stories there are, of course, two voices. In this one, the inside voice, Bizco, an unreliable narrator, tells a story to the outside voice of how the political prisoners exacted revenge on the common prisoners who had been harassing them. Bizco doesn’t end the story but merely stops talking. I sensed another voice or style, that of the translator and editor, Andrea Gibbons.I chose Penny Mickelbury’s “Murder...Then and Now” to get a sense of what she is about before reading her novels, which I have on my shelf among the African American writers of crime and mystery fiction. In a town in the northeast, the KKK plans to march down the main street and burn an effigy of Black Power. To express their anger, five Black students from the unnamed university plan to throw Molotov cocktails on the roof of the police station where the KKK meet. In the “Then” section, before the students can carry out their plan, two of the them are murdered and a third is charged. In the “Now” section, forty years later, a fourth student is murdered. To describe the motive and method of the murders would be a spoiler. A good story that makes its point without hitting you over the head: beware of betrayal.

Location:

Knoxville, TN, USA

24 August 2013

3D Printing: the Next Big Thing

by Elizabeth Zelvin

I've been hearing a lot lately about 3D printing—or producing or constructing or “making.” I was excited enough to write a post about it on my other group mystery blog, and it surprised me that the topic got so little response. I can't believe the SleuthSayers and their (our) friends won't have more to say about this the-future-as-predicted-in-science-fiction-has-arrived technology. In fact, one of us, I think Leigh, was right on top of the story about the 3D-printed gun.

My hubby was particularly annoyed that all the hoopla about weapons cast all the extraordinary constructive uses of 3D making, present and projected, into the shade. He started bringing information and whatever samples he could get his hands on home after going to an exhibition of the latest 3D technology (he uses high-end copiers in his job at a university) and visiting a store in lower Manhattan called MakerBot where you can actually buy a "replicator"—a term long familiar to Star Trek fans—for the home.

My hubby was particularly annoyed that all the hoopla about weapons cast all the extraordinary constructive uses of 3D making, present and projected, into the shade. He started bringing information and whatever samples he could get his hands on home after going to an exhibition of the latest 3D technology (he uses high-end copiers in his job at a university) and visiting a store in lower Manhattan called MakerBot where you can actually buy a "replicator"—a term long familiar to Star Trek fans—for the home.

I also saw a YouTube video of in which the son of an old friend introduced the speaker at a design event in San Francisco about “the maker movement.” He said: “With simple and affordable 3D design software... access to digital fabrication services, [and] desktop 3D printers, ‘makers’ are turning their home offices into home factories.”

On the face of it, this new technology is a good thing. The speaker my friend’s son introduced was the CEO of TechShop, which bills itself as “America’s first nationwide open access public workshop.” From the website: “TechShop is a playground for creativity. Part fabrication and prototyping studio, part hackerspace and part learning center, TechShop provides access to over $1 million worth of professional equipment and software...at TechShop you can explore the world of making in a collaborative and creative environment.”

Among the applications of 3D technology already in use is the making of relatively inexpensive prototypes of any kind of design. My husband brought home a cute little nut and bolt from the convention center exhibit (as at most conventions nowadays, there weren’t a whole lot of freebies) and a brightly colored expansion bracelet from the 3D store. Printed items listed on the site 3Ders.org include a robot that scoots along power lines checking for damage, individualized shoes in custom sizes, toys, high-performance bike parts, and fashion sunglasses.

Among the applications of 3D technology already in use is the making of relatively inexpensive prototypes of any kind of design. My husband brought home a cute little nut and bolt from the convention center exhibit (as at most conventions nowadays, there weren’t a whole lot of freebies) and a brightly colored expansion bracelet from the 3D store. Printed items listed on the site 3Ders.org include a robot that scoots along power lines checking for damage, individualized shoes in custom sizes, toys, high-performance bike parts, and fashion sunglasses.

Medical applications are also in use. An article on 3Ders.org describes how doctors are creating 3D-printed models of patients’ bone structure and organs to prepare for complex surgery. “Since the model is a facsimile of the patient's actual physiology, surgeons can use it to precisely shape metal inserts that fit along a patient's residual bone.” Even better, the patient spends less time in actual surgery, substantially reducing the risk of things going wrong.

And then there's the gun. I'm a mystery writer. Of course I'd thought of it the moment I heard about 3D technology. A May 5 article on 3Ders.org reported:

“Defense Distributed showed off the world's first entirely 3D printed gun last Friday and announced its plan to publish the blueprints for ‘The Liberator’ on its blueprints archive Defcad.org this week.

There was a big brouhaha about it in both government and the media. Guns aren't mentioned on the home page of 3Ders.org today (as I write this on June 6, getting ahead with my posts). The lead story is: "3D printed mini yellow ducks debut in Hong Kong."

There was a big brouhaha about it in both government and the media. Guns aren't mentioned on the home page of 3Ders.org today (as I write this on June 6, getting ahead with my posts). The lead story is: "3D printed mini yellow ducks debut in Hong Kong."

Like every innovation in history, this new technology can be used for good or ill, depending on what people choose to make of it both literally and figuratively.

23 August 2013

The Immortal Timing of Elmore Leonard

by Dixon Hill

Buddy Hackett said, “Ask me what’s the secret of comedy.”

Johnny Carson started to say, “What’s the secret of…” and Buddy yelled, “Timing,” very loudly, right in his face. It killed me. Timing is important — Johnny Carson has a throw pillow in his house that has embroidered on it, “It’s All in the Timing.”

The excerpt above is from How To Play In Traffic by Penn Jillette and Teller, published in 1997 and reportedly now out of print. But, whether or not the book’s out of print, this excerpt deftly demonstrates comedy timing.

Or, perhaps in this case: counter-timing.

Timing isn’t only important in comedy, of course; it’s crucial in many sports, such as archery or running (when should a runner add that final burst of speed, for instance?). And, in my opinion, timing is also often crucial to the success of a story.

Whether that story’s a suspense, mystery, romance, or even literary, timing often makes as big a difference between “hit” or “miss,” as it does on the archery range. Just the right “oomph” has to come at just the right moment, after a long period of climbing tension, or everything can fall flat and lifeless.

This is one problem I don’t believe the late Elmore Leonard suffered from.

In fact—comedic timing or suspense timing—I think he had a great sense of both. How else could he have turned out a work like Get Shorty?

Frankly, I believe folks will be reading Elmore Leonard for decades, if not centuries to come. And, though the reasons they sight for reading him may change over time, I believe his “timing” will be a major ingredient for his writing’s longevity, perhaps even immortality.

How did he do it?

A comedian can physically stop speaking, wait a beat or half-beat, then deliver the punch line. But, how does one accomplish the same thing in the written word?

A writer can’t very well write “Stop and wait a beat before reading the next sentence, please.” Yet, Elmore Leonard’s timing was terrific.

I believe Leonard gave us a pretty good hint, four years ago on Criminal Brief, when he wrote: “I’m a believer in white space, the setting off of text (and illustrations) with surrounding ‘emptiness’ to lend readability and visual attraction. William Morrow and HarperCollins charge dearly for white space. …”

He wasn’t necessarily talking about timing when wrote that. But, I strongly suspect his belief in the “white space” had a lot to do with his success in timing.

Think about it:

How often does a comedian wind along on a story, raising the comedic tension — only to suddenly drop into silence for a beat, before delivering a verbal snap-kick that sends the audience reeling?

That silent beat, or half-beat, is timing.

And, in the written word as Elmore Leonard dished it up, I think the printed equivalent was often hidden in the white space he so revered.

If white space, alone, did the trick, of course, I’m sure we’d see far more books with two or three lines of blank space between certain lines. And, that’s not terribly common, even in Elmore Leonard’s work. In fact, thumbing through four of his novels while researching this column, I found that he only did that to denote scene changes — a pretty common practice, I’m sure you’ll agree.

So, how does white space help with timing?

I think the answer is that it works in the interplay of other elements. In that same post on Criminal Brief, Leonard posted his ten tips for writers as follows:

Taken together, and in conjunction with a statement he made around the same time: “My most important rule is one that sums up the 10: If it sounds like writing, I rewrite it,” we’re left with a clear understanding of his desire to achieve spare or stripped-down writing.

I took the opportunity to examine this list on a few other sites, and found it interesting, however, that Mr. Leonard made it clear: There is room for compromise.

As he pointed out at one point: these are ten rules that work for him; he’s not suggesting they work for everyone. In one case he explains, “If you happen to be Barry Lopez, who has more ways than an Eskimo to describe ice and snow in his book Arctic Dreams, you can do all the weather reporting you want.”

More importantly, he adds: ‘There is a prologue in John Steinbeck's Sweet Thursday, but it's OK because a character in the book makes the point of what my rules are all about. He says: "I like a lot of talk in a book and I don't like to have nobody tell me what the guy that's talking looks like. I want to figure out what he looks like from the way he talks."’

Reading what a character says, translating that into the “the way he talks” and using this to create a visual construct of the character may seem to be asking a lot from the reader. But, in an Elmore Leonard work it seems only natural.

He writes the character so that a reader can hear the cadence of that character’s voice, the “beat” of his words. Sometimes, it’s a staccato beat. At others, it’s a languid throb. But the beat is there! And, injecting abundant white space, which is the natural outcome of spare writing, in just the right way, can then create a gestalt of sorts that results in remarkable literary timing—right there on the page.

Is this idea crazy?

According to the New York Times, Mr. Leonard said: “The bad guys are the fun guys. … The only people I have trouble with are the so-called normal types. Their language isn’t very colorful, and they don’t talk with any certain sound.”

Of course, timing has to fit naturally into the voice that’s present, or the slight gear-change required to assure proper timing may signal a ‘heads-up!’ to the reader. This might work on occasion, but I suspect a more subtle manifestation of timing renders a bigger response on the part of the reader.

And, Elmore Leonard was a master of this. Perhaps that's why so many of his narrative view points seem to stem from the so-called 'bad guys;' perhaps they provided voices with the requisite cadence for successful timing.

Or, maybe I'm wrong.

One final comment on Mr. Leonard’s timing:

He passed away in his Bloomfield Township, Mich. home on Tuesday. And, the timing of his passing—from the viewpoint of this reader was:

Johnny Carson started to say, “What’s the secret of…” and Buddy yelled, “Timing,” very loudly, right in his face. It killed me. Timing is important — Johnny Carson has a throw pillow in his house that has embroidered on it, “It’s All in the Timing.”

The excerpt above is from How To Play In Traffic by Penn Jillette and Teller, published in 1997 and reportedly now out of print. But, whether or not the book’s out of print, this excerpt deftly demonstrates comedy timing.

Or, perhaps in this case: counter-timing.

Timing isn’t only important in comedy, of course; it’s crucial in many sports, such as archery or running (when should a runner add that final burst of speed, for instance?). And, in my opinion, timing is also often crucial to the success of a story.

|

| In Memoriam |

Whether that story’s a suspense, mystery, romance, or even literary, timing often makes as big a difference between “hit” or “miss,” as it does on the archery range. Just the right “oomph” has to come at just the right moment, after a long period of climbing tension, or everything can fall flat and lifeless.

This is one problem I don’t believe the late Elmore Leonard suffered from.

In fact—comedic timing or suspense timing—I think he had a great sense of both. How else could he have turned out a work like Get Shorty?

Frankly, I believe folks will be reading Elmore Leonard for decades, if not centuries to come. And, though the reasons they sight for reading him may change over time, I believe his “timing” will be a major ingredient for his writing’s longevity, perhaps even immortality.

How did he do it?

A comedian can physically stop speaking, wait a beat or half-beat, then deliver the punch line. But, how does one accomplish the same thing in the written word?

A writer can’t very well write “Stop and wait a beat before reading the next sentence, please.” Yet, Elmore Leonard’s timing was terrific.

I believe Leonard gave us a pretty good hint, four years ago on Criminal Brief, when he wrote: “I’m a believer in white space, the setting off of text (and illustrations) with surrounding ‘emptiness’ to lend readability and visual attraction. William Morrow and HarperCollins charge dearly for white space. …”

He wasn’t necessarily talking about timing when wrote that. But, I strongly suspect his belief in the “white space” had a lot to do with his success in timing.

Think about it:

How often does a comedian wind along on a story, raising the comedic tension — only to suddenly drop into silence for a beat, before delivering a verbal snap-kick that sends the audience reeling?

That silent beat, or half-beat, is timing.

And, in the written word as Elmore Leonard dished it up, I think the printed equivalent was often hidden in the white space he so revered.

If white space, alone, did the trick, of course, I’m sure we’d see far more books with two or three lines of blank space between certain lines. And, that’s not terribly common, even in Elmore Leonard’s work. In fact, thumbing through four of his novels while researching this column, I found that he only did that to denote scene changes — a pretty common practice, I’m sure you’ll agree.

So, how does white space help with timing?

I think the answer is that it works in the interplay of other elements. In that same post on Criminal Brief, Leonard posted his ten tips for writers as follows:

- Never open a book with weather.

- Avoid prologues.

- Never use a verb other than "said" to carry dialogue.

- Never use an adverb to modify the verb "said,” he admonished gravely.

- Keep your exclamation points under control. You are allowed no more than two or three per 100,000 words of prose.

- Never use the words "suddenly" or "all hell broke loose."

- Use regional dialect, patois, sparingly.

- Avoid detailed descriptions of characters.

- Don’t go into great detail describing places and things.

- Try to leave out the part that readers tend to skip.

Taken together, and in conjunction with a statement he made around the same time: “My most important rule is one that sums up the 10: If it sounds like writing, I rewrite it,” we’re left with a clear understanding of his desire to achieve spare or stripped-down writing.

I took the opportunity to examine this list on a few other sites, and found it interesting, however, that Mr. Leonard made it clear: There is room for compromise.

As he pointed out at one point: these are ten rules that work for him; he’s not suggesting they work for everyone. In one case he explains, “If you happen to be Barry Lopez, who has more ways than an Eskimo to describe ice and snow in his book Arctic Dreams, you can do all the weather reporting you want.”

More importantly, he adds: ‘There is a prologue in John Steinbeck's Sweet Thursday, but it's OK because a character in the book makes the point of what my rules are all about. He says: "I like a lot of talk in a book and I don't like to have nobody tell me what the guy that's talking looks like. I want to figure out what he looks like from the way he talks."’

Reading what a character says, translating that into the “the way he talks” and using this to create a visual construct of the character may seem to be asking a lot from the reader. But, in an Elmore Leonard work it seems only natural.

He writes the character so that a reader can hear the cadence of that character’s voice, the “beat” of his words. Sometimes, it’s a staccato beat. At others, it’s a languid throb. But the beat is there! And, injecting abundant white space, which is the natural outcome of spare writing, in just the right way, can then create a gestalt of sorts that results in remarkable literary timing—right there on the page.

Is this idea crazy?

According to the New York Times, Mr. Leonard said: “The bad guys are the fun guys. … The only people I have trouble with are the so-called normal types. Their language isn’t very colorful, and they don’t talk with any certain sound.”

Of course, timing has to fit naturally into the voice that’s present, or the slight gear-change required to assure proper timing may signal a ‘heads-up!’ to the reader. This might work on occasion, but I suspect a more subtle manifestation of timing renders a bigger response on the part of the reader.

And, Elmore Leonard was a master of this. Perhaps that's why so many of his narrative view points seem to stem from the so-called 'bad guys;' perhaps they provided voices with the requisite cadence for successful timing.

Or, maybe I'm wrong.

One final comment on Mr. Leonard’s timing:

He passed away in his Bloomfield Township, Mich. home on Tuesday. And, the timing of his passing—from the viewpoint of this reader was:

“Too Soon! Oh, far too soon.”

Labels:

Dixon Hill,

Elmore Leonard,

mysteries,

tips,

writing

Location:

Scottsdale, AZ, USA

22 August 2013

Going to Great (or Short) Lengths

by Janice Law

Appearing in a volume of short mysteries, Kwik Krimes has gotten me thinking about writing lengths. Although some of my SleuthSayers colleagues will surely disagree, I am convinced that most writers have a favored length or lengths. Lengths in my case. The Anna Peters novels rarely ran more than 240 pages in typescript; my latest straight mystery, Fires of London, was about the same length and with the new, smaller modern type, printed up to 174 pages. My stand alone novels, on the other hand, are in the 350 page range, while my short stories cluster between 12- 17 pages in typescript, with most in the 14-15 page range.

Why this should be so, I have no idea. I just know that beyond a certain length lies the literary equivalent of the Empty Quarter. The Muse has decamped and taken all my ideas with her. As for the very short, I find it intensely frustrating as the required word limit looms when I’ve barely gotten started.

It seems that the big, multi-generation saga, the weighty blockbuster thriller, and the thousand page romance are not to be in my repertory, nor, at the other end of the spectrum, is flash fiction. I’m not alone in this. Ray Bradbury wrote short; Stephen King writes long. Ruth Rendall is on the short side of the ledger, though the novels of her alter ego, Barbara Vine, run at least a hundred pages more. Elizabeth George’s novels started long and are getting steadily longer; the late, under-rated Magdalen Nabb wrote blessedly short, while my two current personal favorites, Fred Vargas and Kate Atkinson, are in the Goldilocks Belt: moderate length and just right.

Classic novels show a similar pattern. Lampedusa’s great The Leopard is short. So is Jane Austen’s work, although most of the other nineteenth century greats favored long. Except for the Christmas Carol, Dickens’ famous novels are all marathons, as are works by Tolstoy and Dostoevsky and most of the novels by George Eliot and Charlotte Bronte, although the latter’s sister Emily produced the great, and compact, Wuthering Heights.

Would Emily Brontë have gone on to write the triple decker novels beloved of the 19th century book trade? One hopes not, as changing lengths is not always a happy thing for a writer. Dick Francis, whose early mysteries I love, started out writing short and tight. Novels like Flying Finish and Nerve were not much over 200 pages in length. Alas, with fame came the pressures for ‘big novels.’ I doubt I’m the only fan who has found his later work much less appealing.

Other writers have had a happier fate. Both P.D. James and John Le Carre produced short early books then hit their stride with the longer and more complex works that have made their reputations. In a reversal of this trajectory, Stephen King has profitably experimented with some short works on line.

Still, my own experience has been that I do my best work within fairly strict lengths. I’ve tried a couple of times to manage Woman’s World’s 600 word limit. Neither was a happy experience, although I recycled one story and sold it to Sherlock Holmes Magazine – but only after I’d expanded the material to my favored length.

So why am I now appearing in Otto Penzler’s Kwik Krimes, a little volume of 1000 word mysteries, along with 80 other people who are perhaps more in touch with brevity than I am?

The answer lies in Samuel Johnson territory. The good doctor, himself, a working writer who had to grub for every shilling, famously said that “No man but a blockhead ever wrote, except for money.” However idealistic a writer is and even however unbusinesslike she may be, the Muse leans to Dr. Johnson’s opinion.

There is something about being asked for a story – how often does that happen!– with the promise of a check to follow that lifts the heart. Most writers’ short stories are composed on spec. They emerge from the teeming brain and are sent on their way with a hopeful query, most likely to be returned with a note that they are “not quite right for us at this time.” One can be sure that they will never will be right at some future time, either.

So, a firm request is a great inspiration. I said I’d give it a try, and voila, an idea presented itself. I proceeded to steal an strategy from one of the greats– only borrow from the very best is my motto– and turned out the 1001 words of “The Imperfect Detective.” A thousand words? Close enough.

Why this should be so, I have no idea. I just know that beyond a certain length lies the literary equivalent of the Empty Quarter. The Muse has decamped and taken all my ideas with her. As for the very short, I find it intensely frustrating as the required word limit looms when I’ve barely gotten started.

It seems that the big, multi-generation saga, the weighty blockbuster thriller, and the thousand page romance are not to be in my repertory, nor, at the other end of the spectrum, is flash fiction. I’m not alone in this. Ray Bradbury wrote short; Stephen King writes long. Ruth Rendall is on the short side of the ledger, though the novels of her alter ego, Barbara Vine, run at least a hundred pages more. Elizabeth George’s novels started long and are getting steadily longer; the late, under-rated Magdalen Nabb wrote blessedly short, while my two current personal favorites, Fred Vargas and Kate Atkinson, are in the Goldilocks Belt: moderate length and just right.

Classic novels show a similar pattern. Lampedusa’s great The Leopard is short. So is Jane Austen’s work, although most of the other nineteenth century greats favored long. Except for the Christmas Carol, Dickens’ famous novels are all marathons, as are works by Tolstoy and Dostoevsky and most of the novels by George Eliot and Charlotte Bronte, although the latter’s sister Emily produced the great, and compact, Wuthering Heights.

Would Emily Brontë have gone on to write the triple decker novels beloved of the 19th century book trade? One hopes not, as changing lengths is not always a happy thing for a writer. Dick Francis, whose early mysteries I love, started out writing short and tight. Novels like Flying Finish and Nerve were not much over 200 pages in length. Alas, with fame came the pressures for ‘big novels.’ I doubt I’m the only fan who has found his later work much less appealing.

Other writers have had a happier fate. Both P.D. James and John Le Carre produced short early books then hit their stride with the longer and more complex works that have made their reputations. In a reversal of this trajectory, Stephen King has profitably experimented with some short works on line.

Still, my own experience has been that I do my best work within fairly strict lengths. I’ve tried a couple of times to manage Woman’s World’s 600 word limit. Neither was a happy experience, although I recycled one story and sold it to Sherlock Holmes Magazine – but only after I’d expanded the material to my favored length.

So why am I now appearing in Otto Penzler’s Kwik Krimes, a little volume of 1000 word mysteries, along with 80 other people who are perhaps more in touch with brevity than I am?

The answer lies in Samuel Johnson territory. The good doctor, himself, a working writer who had to grub for every shilling, famously said that “No man but a blockhead ever wrote, except for money.” However idealistic a writer is and even however unbusinesslike she may be, the Muse leans to Dr. Johnson’s opinion.

There is something about being asked for a story – how often does that happen!– with the promise of a check to follow that lifts the heart. Most writers’ short stories are composed on spec. They emerge from the teeming brain and are sent on their way with a hopeful query, most likely to be returned with a note that they are “not quite right for us at this time.” One can be sure that they will never will be right at some future time, either.

So, a firm request is a great inspiration. I said I’d give it a try, and voila, an idea presented itself. I proceeded to steal an strategy from one of the greats– only borrow from the very best is my motto– and turned out the 1001 words of “The Imperfect Detective.” A thousand words? Close enough.

21 August 2013

Five Red Herrings V

1. Sherlock and key

Got a from Sherlock Holmes Mystery Magazine in early March describing a fascinating event in their lives. Like good citizens they had purchased the right to use the Master's name on their magazine. Unfortunately the person who sold them said rights apparently didn't own them. Oopsies. Do a search for Andrea Plunkit and Doyle estate if you want the gory details.

2. Insecurity Questions

2. Insecurity Questions

Wondermark is one of the most delightfully bizarre comic strips on the web. Monty Python goes cyberpunk, sort of.

3. Harlan Coben, here is the plot for your next novel

3. Harlan Coben, here is the plot for your next novel

When Lori Ruff died in Seattle she left a strongbox full of secrets. They made it clear that the wife and mother was living under a stolen identity. But who she was originally and why she changed her name, well, her husband would sure like to know. From the Seattle Times.

4. James Powell is going to happen

I don't know if you follow Something Is Going To Happen, the blog at Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine, but they recently published a wild piece by Jim Powell who demonstrates that at an age even more advanced than my own he has a crazier imagination than any teenage gamer every dreamed of. Watch him free associate...

Though it isn’t a mystery story, Edgar Allan Poe’s

“The Man in the Crowd” may be the short story at it’s best, for there

are really only two characters, the man and the crowd. (Speaking of Poe,

it has been a long time since the Sherlock Holmsing pigeon drove the

Raven “nevermoring” all the way, from its perch on the bust of Pallas

just above Poe’s chamber door only to come back to us again as a good

part of Johnny Depp’s Tonto headgear in the new Lone Ranger movie.

Sherlock’s pigeon would be replaced a few years later by the Maltese

Falcon. I wonder what kind of bird will come next to roost on that

well-encrusted and put upon piece of statuary?)

Though it isn’t a mystery story, Edgar Allan Poe’s

“The Man in the Crowd” may be the short story at it’s best, for there

are really only two characters, the man and the crowd. (Speaking of Poe,

it has been a long time since the Sherlock Holmsing pigeon drove the

Raven “nevermoring” all the way, from its perch on the bust of Pallas

just above Poe’s chamber door only to come back to us again as a good

part of Johnny Depp’s Tonto headgear in the new Lone Ranger movie.

Sherlock’s pigeon would be replaced a few years later by the Maltese

Falcon. I wonder what kind of bird will come next to roost on that

well-encrusted and put upon piece of statuary?)

5. They were steampunk before steampunk was cool.

Have you seen the website Murder by Gaslight? True crimes of Victorian England. Quick, Watson! Call C.S.I.!

Have you seen the website Murder by Gaslight? True crimes of Victorian England. Quick, Watson! Call C.S.I.!

Got a from Sherlock Holmes Mystery Magazine in early March describing a fascinating event in their lives. Like good citizens they had purchased the right to use the Master's name on their magazine. Unfortunately the person who sold them said rights apparently didn't own them. Oopsies. Do a search for Andrea Plunkit and Doyle estate if you want the gory details.

2. Insecurity Questions

2. Insecurity Questions Wondermark is one of the most delightfully bizarre comic strips on the web. Monty Python goes cyberpunk, sort of.

3. Harlan Coben, here is the plot for your next novel

3. Harlan Coben, here is the plot for your next novel When Lori Ruff died in Seattle she left a strongbox full of secrets. They made it clear that the wife and mother was living under a stolen identity. But who she was originally and why she changed her name, well, her husband would sure like to know. From the Seattle Times.

4. James Powell is going to happen

I don't know if you follow Something Is Going To Happen, the blog at Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine, but they recently published a wild piece by Jim Powell who demonstrates that at an age even more advanced than my own he has a crazier imagination than any teenage gamer every dreamed of. Watch him free associate...

Though it isn’t a mystery story, Edgar Allan Poe’s

“The Man in the Crowd” may be the short story at it’s best, for there

are really only two characters, the man and the crowd. (Speaking of Poe,

it has been a long time since the Sherlock Holmsing pigeon drove the

Raven “nevermoring” all the way, from its perch on the bust of Pallas

just above Poe’s chamber door only to come back to us again as a good

part of Johnny Depp’s Tonto headgear in the new Lone Ranger movie.

Sherlock’s pigeon would be replaced a few years later by the Maltese

Falcon. I wonder what kind of bird will come next to roost on that

well-encrusted and put upon piece of statuary?)

Though it isn’t a mystery story, Edgar Allan Poe’s

“The Man in the Crowd” may be the short story at it’s best, for there

are really only two characters, the man and the crowd. (Speaking of Poe,

it has been a long time since the Sherlock Holmsing pigeon drove the

Raven “nevermoring” all the way, from its perch on the bust of Pallas

just above Poe’s chamber door only to come back to us again as a good

part of Johnny Depp’s Tonto headgear in the new Lone Ranger movie.

Sherlock’s pigeon would be replaced a few years later by the Maltese

Falcon. I wonder what kind of bird will come next to roost on that

well-encrusted and put upon piece of statuary?)5. They were steampunk before steampunk was cool.

Have you seen the website Murder by Gaslight? True crimes of Victorian England. Quick, Watson! Call C.S.I.!

Have you seen the website Murder by Gaslight? True crimes of Victorian England. Quick, Watson! Call C.S.I.!

Labels:

cartoons,

Ellery Queen,

EQMM,

James Powell,

Lopresti,

mystery magazine,

Seattle,

Sherlock Holmes,

SHMM,

Victorian England

20 August 2013

Sic Transit Gloria, Mason

Have you ever heard of F. Van Wyck Mason? I couldn't place the name when I stumbled across it recently. Since then, it's been on my mind. But let me start at the beginning.

Earlier this year, Alfred Hitchcock's Mystery Magazine published a story of mine, "Margo and the Silver Cane," that I'm hoping will be the first installment of a new series. It features a young woman working in radio in New York City in 1941 who finds herself drafted into an amateur counterespionage operation.

For a Margo story I was writing a few weeks back, "Margo and the Milk Trap," I needed a few titles of bestselling novels from 1940. Once upon a time, filling that need would have meant a drive down to the central library and a visit to the microfilm room to look over old reels of the New York Times. Nowadays, one can simply do a search on Google or Bing or whatever for something that sounds like an unproduced Busby Berkeley musical: "Bestsellers of 1940." So that's what I did. Most of the titles and authors on the resulting list were familiar, either from my past reading or from film adaptations. But one author-title combination was completely unfamiliar. It was Stars on the Sea, by F. Van Wyck Mason.

Intrigued (and, as always, easily distracted), I did a search on Mason's long name and found a Wikipedia entry. It turns out that Mason was a fellow mystery writer. He was also a writer of historical novels for both adults and young adults and a decorated veteran of both world wars. He died on August 28, 1978, thirty-five years ago next Wednesday. And I couldn't remember ever hearing his name.

After Mason's somewhat improbable service in World War I (he was a seventeen-year-old lieutenant when the war ended), he attended Harvard and started an importing business that took him to many exotic places around the world. Sometime in the late 1920s, he began writing short stories for pulp magazines. His success at this was described thusly by Wikipedia: "The magazines paid well at this time and he was able to build a comfortable home outside Baltimore, Maryland." (Sigh.)

In 1930, Mason began a long-running mystery series featuring Hugh North, army intelligence officer and James Bond precursor. The first title in the series was the appropriately named Seeds of Murder. The last in the series was 1968's The Deadly Orbit Mission. By the late 1930s, Mason was doing so well he was able to "split his time between Nantucket, Bermuda, and Maryland." (Heavy sigh.)

During the war, Mason served as Eisenhower's staff historian and was with the first troops to enter Buchenwald. After the war, he resumed writing the North series and his historical novels (Stars on the Sea, his prewar bestseller, was one of these) and started writing historicals for the school kid market, under the name Frank W. Mason. (Early on, he seems to have written mysteries as "Van Wyck Mason" and historicals as "F. Van Wyck Mason." Later, this distinction went away.) When he died in 1978--drowning while swimming off Bermuda--he'd published over seventy books.

After squeezing Wikipedia dry, I found my curiosity was far from satisfied. I switched over to Amazon to order a Hugh North mystery from a used book seller. The book I selected was The Shanghai Bund Murders from 1933. In it, North must solve a series of murders and decipher a dying man's cryptic last words in order to save Shanghai from a bloodthirsty war lord. Politically correct, it ain't. North is the kind of lean, tight-lipped hero who is always ratcheting up his keen powers of perception to a perceptively keener power, but by the end, I was rooting for him. That ending left me wondering if Ian Fleming, James Bond's creator, had read The Shanghai Bund Murders before starting Dr. No. North ends up a prisoner in an underground torture chamber and, to escape, he must wiggle out through a sewer. The description of that wiggling is not for the claustrophobic. (There's another curious link between Mason and Bond. 007's birthday, according to experts on the subject, is November 11, the same as Mason's.)

After squeezing Wikipedia dry, I found my curiosity was far from satisfied. I switched over to Amazon to order a Hugh North mystery from a used book seller. The book I selected was The Shanghai Bund Murders from 1933. In it, North must solve a series of murders and decipher a dying man's cryptic last words in order to save Shanghai from a bloodthirsty war lord. Politically correct, it ain't. North is the kind of lean, tight-lipped hero who is always ratcheting up his keen powers of perception to a perceptively keener power, but by the end, I was rooting for him. That ending left me wondering if Ian Fleming, James Bond's creator, had read The Shanghai Bund Murders before starting Dr. No. North ends up a prisoner in an underground torture chamber and, to escape, he must wiggle out through a sewer. The description of that wiggling is not for the claustrophobic. (There's another curious link between Mason and Bond. 007's birthday, according to experts on the subject, is November 11, the same as Mason's.)

So why is F. Van Wyck Mason so little known today? For mystery fans, like me, it may be because Hugh North gave up solving murders sometime after World War II and evolved into an espionage agent. It may be because Hollywood never clasped North to its celluloid bosom. Or perhaps the question should be stated differently: How does any popular author stay popular, with so many shiny new ones hitting showroom floors every year?

I don't know the answer to either question, but next Wednesday I'll be lifting a highball (North favored them) to F. Van Wyck Mason and to all those dead magazines that paid him so well.

Earlier this year, Alfred Hitchcock's Mystery Magazine published a story of mine, "Margo and the Silver Cane," that I'm hoping will be the first installment of a new series. It features a young woman working in radio in New York City in 1941 who finds herself drafted into an amateur counterespionage operation.

For a Margo story I was writing a few weeks back, "Margo and the Milk Trap," I needed a few titles of bestselling novels from 1940. Once upon a time, filling that need would have meant a drive down to the central library and a visit to the microfilm room to look over old reels of the New York Times. Nowadays, one can simply do a search on Google or Bing or whatever for something that sounds like an unproduced Busby Berkeley musical: "Bestsellers of 1940." So that's what I did. Most of the titles and authors on the resulting list were familiar, either from my past reading or from film adaptations. But one author-title combination was completely unfamiliar. It was Stars on the Sea, by F. Van Wyck Mason.

|

| F. Van Wyck Mason |

After Mason's somewhat improbable service in World War I (he was a seventeen-year-old lieutenant when the war ended), he attended Harvard and started an importing business that took him to many exotic places around the world. Sometime in the late 1920s, he began writing short stories for pulp magazines. His success at this was described thusly by Wikipedia: "The magazines paid well at this time and he was able to build a comfortable home outside Baltimore, Maryland." (Sigh.)

In 1930, Mason began a long-running mystery series featuring Hugh North, army intelligence officer and James Bond precursor. The first title in the series was the appropriately named Seeds of Murder. The last in the series was 1968's The Deadly Orbit Mission. By the late 1930s, Mason was doing so well he was able to "split his time between Nantucket, Bermuda, and Maryland." (Heavy sigh.)

During the war, Mason served as Eisenhower's staff historian and was with the first troops to enter Buchenwald. After the war, he resumed writing the North series and his historical novels (Stars on the Sea, his prewar bestseller, was one of these) and started writing historicals for the school kid market, under the name Frank W. Mason. (Early on, he seems to have written mysteries as "Van Wyck Mason" and historicals as "F. Van Wyck Mason." Later, this distinction went away.) When he died in 1978--drowning while swimming off Bermuda--he'd published over seventy books.

After squeezing Wikipedia dry, I found my curiosity was far from satisfied. I switched over to Amazon to order a Hugh North mystery from a used book seller. The book I selected was The Shanghai Bund Murders from 1933. In it, North must solve a series of murders and decipher a dying man's cryptic last words in order to save Shanghai from a bloodthirsty war lord. Politically correct, it ain't. North is the kind of lean, tight-lipped hero who is always ratcheting up his keen powers of perception to a perceptively keener power, but by the end, I was rooting for him. That ending left me wondering if Ian Fleming, James Bond's creator, had read The Shanghai Bund Murders before starting Dr. No. North ends up a prisoner in an underground torture chamber and, to escape, he must wiggle out through a sewer. The description of that wiggling is not for the claustrophobic. (There's another curious link between Mason and Bond. 007's birthday, according to experts on the subject, is November 11, the same as Mason's.)

After squeezing Wikipedia dry, I found my curiosity was far from satisfied. I switched over to Amazon to order a Hugh North mystery from a used book seller. The book I selected was The Shanghai Bund Murders from 1933. In it, North must solve a series of murders and decipher a dying man's cryptic last words in order to save Shanghai from a bloodthirsty war lord. Politically correct, it ain't. North is the kind of lean, tight-lipped hero who is always ratcheting up his keen powers of perception to a perceptively keener power, but by the end, I was rooting for him. That ending left me wondering if Ian Fleming, James Bond's creator, had read The Shanghai Bund Murders before starting Dr. No. North ends up a prisoner in an underground torture chamber and, to escape, he must wiggle out through a sewer. The description of that wiggling is not for the claustrophobic. (There's another curious link between Mason and Bond. 007's birthday, according to experts on the subject, is November 11, the same as Mason's.)So why is F. Van Wyck Mason so little known today? For mystery fans, like me, it may be because Hugh North gave up solving murders sometime after World War II and evolved into an espionage agent. It may be because Hollywood never clasped North to its celluloid bosom. Or perhaps the question should be stated differently: How does any popular author stay popular, with so many shiny new ones hitting showroom floors every year?

I don't know the answer to either question, but next Wednesday I'll be lifting a highball (North favored them) to F. Van Wyck Mason and to all those dead magazines that paid him so well.

Labels:

F. Van Wyck Mason,

forgotten,

Hugh North,

Terence Faherty,

writers

19 August 2013

Lessons Learned

by Jan Grape

Lawrence Block wrote an excellent article on procrastination in his book, Telling Lies For Fun And Profit. The book is a collection of the columns Mr. Block wrote for Writer's Digest. In the article he talks about Creative Procrastination, the time we sometimes spend doing things other than writing. Not always, but often that time is really when our subconscious works on our story. Yes, really. Of course, that's not always the case. Often writers just put off writing and doing other things. I've vacuumed floors, cleaned bathrooms, done laundry, taken a walk or a shower just to keep from sitting down and working on my WIP (work in progress.) But he isn't saying to become a sloth either. What you have isn't necessarily writer's block.

Lawrence Block wrote an excellent article on procrastination in his book, Telling Lies For Fun And Profit. The book is a collection of the columns Mr. Block wrote for Writer's Digest. In the article he talks about Creative Procrastination, the time we sometimes spend doing things other than writing. Not always, but often that time is really when our subconscious works on our story. Yes, really. Of course, that's not always the case. Often writers just put off writing and doing other things. I've vacuumed floors, cleaned bathrooms, done laundry, taken a walk or a shower just to keep from sitting down and working on my WIP (work in progress.) But he isn't saying to become a sloth either. What you have isn't necessarily writer's block.We may have a general idea of the next book, or chapter or scene but feel things are not quite jelling. It just may be we need a Time Out, which is the next chapter subject in Larry's book. If we have a deadline we can usually force ourselves to set a schedule. Write so many hours or pages or words per day and get our deadline met. Other times we drag ourselves to the computer and maybe miss our goal for the day by a long shot.

Perhaps the scene or chapter isn't working for some reason and we have no idea why. It's just not totally wrong to take a walk or do the laundry. A little creative procrastination or a little time out is probably what our creative brain needs. I'm always amazed when I think how the subconscious works. Mainly I try not to think about my muse. Because if I try to wrestle it to hop into action, it has a tendency to tell me to go jump off a cliff.

However, if I take a time out and let the whole thing simmer on the back burner for a little while, things seem to straighten out completely. I can sit down at the computer and the words will flow. A direct line from my brain to my fingertips and I almost can't type fast enough.

The flip side, naturally, is even after a time out, maybe of a few hours or a day, things still seem muddled and I know I have a schedule or a deadline then I have to sit my behind down in the chair and write. And keep writing.

Oftentimes when I'm writing, I think the work is going badly. That all I'm writing is total junk; I have to keep writing. I have to realize the editor portion of my brain is trying to take over and I have to tell it to "shut up and go away." I've learned that usually the next day what I wrote before isn't half bad. I know that every word I write isn't going to sing but I need to stay on task. That once I'm at the end of the story and write the end I'll be able to look at it more objectively.

Once I set the work aside, two or three days, or even a week, and pull it out I'll find that it's pretty danged good. I can see where I need to revise. Increase tension. Strengthen a character. Or even delete a page or three. That's where the revisions come in. Some writers hate revising. I mainly don't mind because I know I can make my story better with revisions.

Someone told me a long time ago, that you have to tell yourself the story first, then you are able to go back and get the story in shape for others to read.

I envy writers who are able to write a book with only a few minor revisions. I'm just not that good. I also am unable to outline a story. I know authors who do a sixty-seventy page outline of their book. I know others who write a brief outline. Maybe three or four pages. If I outline, it's like talking too much about the book. I get bored if I know too much. I do a whole lot better when I fly by the seat of my pants. I have sometimes made a brief outline when I feel I'm about at the halfway point. Mostly so I can see if I need to add or subtract an element. Generally, I know how the book ends but not always whodunit. Feels like it works better for me if I fool myself then maybe the reader will be fooled. But basically I'm not concerned with the plot because my major thing is my characters.

Okay class, let's recap. Allow yourself some creative procrastination or time out. Don't beat yourself up if it seems like things are going badly. Most of the time, they're not. If you really want to learn more about these subjects and how to deal with them, find a copy of Lawrence Block's book, Telling Lies.

And remember, each writer has to do what works best for them.+

Labels:

Jan Grape,

Lawrence Block,

schedules,

subconsciousness,

writing

Location:

Cottonwood Shores, TX, USA

18 August 2013

The Truth shall set thee free

by Leigh Lundin

by Leigh Lundin

For at least the past half century, clerks and bureaucrats offer consumers the excuse “It’s not our fault, the computer made a mistake.” As a computer specialist, I know that behind a mistake is another human and the proffered excuse is an attempt to mitigate or evade responsibility. It’s not that computers are infallible, but they do what people tell them to do.

Friday morning I was listening to CNN pontificate about the Edward Snowden affair. Their hostess pointed out that people either believe he’s a hero or a traitor. I’m not sure this reflects political leanings but the guest on the left took the position Snowden’s a betrayer whilst the guy on the right claimed Snowden’s a patriot. I never did hear anything of importance from the guest in the middle, but my mind may have tuned out following an amazing, jaw-dropping, mind-numbing statement: The NSA apologist (the guy on the left of the screen) said something to the effect we can’t so much blame NSA’s crimes on people, because these crimes are committed by computers.

Wh– what?

Going back to my opening paragraph, computers do what people tell them to do. In centuries past, defendants might have tried “Your Honour, t'were me fourteen vicious dogs wot ripped apart me wife’s paramour all on their own selves,” or “It were an accident pure and simple, Judge. Me horse reared up and clopped the landlord on ’is head.”

But blaming computers, it’s like saying:

For at least the past half century, clerks and bureaucrats offer consumers the excuse “It’s not our fault, the computer made a mistake.” As a computer specialist, I know that behind a mistake is another human and the proffered excuse is an attempt to mitigate or evade responsibility. It’s not that computers are infallible, but they do what people tell them to do.

| Reflection |

|---|

| In a couple of small towns where I grew up, town gossips considered their mission to find out about everyone else’s business while hiding the skeletons in their own closets. One of the women complained her husband wouldn’t share the tidbits he picked up at the local grain elevator. He became my hero. Some victims must have felt vindication when one of the worst dashed back and forth, spying upon her own daughter making out in her boyfriend’s car in front of her house, then running to the back bathroom, climbing up on the tub and peering out the rear window spying on another couple having at it. In her gusto, she slipped on the tub, fell and broke her arm. Her screams and the subsequent ambulance brought all pleasurable activities to a halt. The lessons I took away was that– private as I am– tight lips and an open bearing is a wise policy. Thus, when it comes to government, I lean towards the-truth-and-damn-the-consequences policy, not in every instance, but the vast majority of the time. And this is what I’ve learned from the Snowden and Manning affairs: Our nation, our government survives pretty damn well when the truth comes out. Might these examples suggest the less secrecy the better? Or at least shouldn’t we open our eyes and engage in a discussion what secrets are wise and what aren’t? |

Friday morning I was listening to CNN pontificate about the Edward Snowden affair. Their hostess pointed out that people either believe he’s a hero or a traitor. I’m not sure this reflects political leanings but the guest on the left took the position Snowden’s a betrayer whilst the guy on the right claimed Snowden’s a patriot. I never did hear anything of importance from the guest in the middle, but my mind may have tuned out following an amazing, jaw-dropping, mind-numbing statement: The NSA apologist (the guy on the left of the screen) said something to the effect we can’t so much blame NSA’s crimes on people, because these crimes are committed by computers.

Wh– what?

Going back to my opening paragraph, computers do what people tell them to do. In centuries past, defendants might have tried “Your Honour, t'were me fourteen vicious dogs wot ripped apart me wife’s paramour all on their own selves,” or “It were an accident pure and simple, Judge. Me horse reared up and clopped the landlord on ’is head.”

But blaming computers, it’s like saying:

- “I didn’t cut them joists too short, my saw did.”

- “Officer, I didn’t run the red light, my car did.”

- “Judge, I didn’t shoot the guy, my Glock did.”

Labels:

computers,

culpability,

Leigh Lundin

Location:

Orlando, FL, USA

17 August 2013

Hail to the Chief

by John Floyd

by John M. Floyd

Rob Lopresti's entertaining column a couple weeks ago about different actors who have played the same detective/sleuth started me thinking. (Always a dangerous thing.) What role, I found myself wondering, would be the most difficult for an actor to take on? A terrorist? A child molester? A serial killer? Possibly--but challenging roles don't always have to be bad guys, right? What if you had to play a familiar, famous, and/or heroic part? Wouldn't that be just as hard to do? If you're the producer, who (besides maybe Clint Eastwood) would you choose to play Jesus Christ, or Jonas Salk, or Jack Kennedy, or Davy Crockett? (I won't list God, here, because in my opinion no one could ever top George Burns.)

With that in mind, consider this puzzle. Your mission, Mr. Phelps, should you choose to accept it, is to match the following twenty actors and the films in which they portrayed a fictional President of the United States. Answers are at the bottom of the column.

With that in mind, consider this puzzle. Your mission, Mr. Phelps, should you choose to accept it, is to match the following twenty actors and the films in which they portrayed a fictional President of the United States. Answers are at the bottom of the column.

(As I tried to recall these roles, I found myself surprised anew by some of the choices the casting folks made to play our Commander-in-Chief--and in some cases found myself wishing we could've swapped out some real-life Presidents for the ones we saw on the screen.)

Here are the candidates:

2. Peter Sellers

3. Morgan Freeman

4. Bill Pullman

5. James Cromwell

6. Harrison Ford

7. Donald Pleasence

8. Jeff Bridges

9. Robert Culp

10. Michael Douglas

11. John Travolta

12. Richard Widmark

13. Kevin Kline

14. Gene Hackman

15. Ronny Cox

16. Cliff Robertson

17. Charles Durning

18. William Hurt

19. Fredrick March

A. Air Force One

B. Seven Days in May

C. The Pelican Brief

D. Escape From New York

E. Absolute Power

F. Dave

G. Vanished