I’m asking for a few other reasons.

One: I was just in a casino—I swear I was there for research—and encountered a ton of slot machines derived from literary works. Willy Wonka slot machines. James Bond slot machines. Game of Thrones, and The Lord of the Rings slot machines. Granted, these slots were devoted to filmed versions of these literary properties. But it nevertheless reminded me that there is big money in keeping the literary heritage of an author as trouble-free as possible. No wonder the heirs of various estates are tempted to permit revision of their ancestor’s work. They want book sales and licensing deals to keep rolling in until the copyrights have expired.

Two: I’m also asking because I recently revisited a couple of books in a mystery series I’d enjoyed as a kid. Those books not only raised the question of revision, but, to my mind, complicated the issue even further. It’s back-to-school time in the U.S., so I thought this might make an interesting conversation. But I warn you right now: I cannot easily answer some of the questions I will pose to you. I actually hope that you can help me.

The Happy Hollisters at Sea Gull Beach is the third book in the series I’m talking about, but it was the first to hook me as a kid. It’s the story of a family of amateur sleuths who search for a long-lost pirate ship while on a beach vacation. When I discovered the book at a library sale in the early 1970s, it struck me as aspirational. A family that goes on a vacation to the beach at a moment’s notice? To solve a mystery? Parents who don’t berate their kids about how much this trip is costing? Sold!

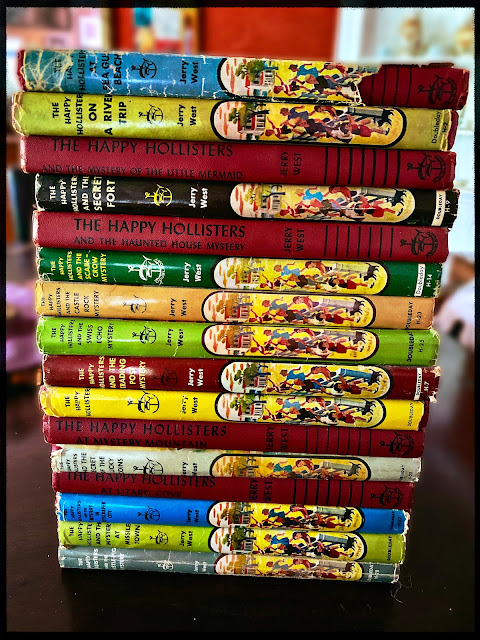

It never occurred to me that the Happy Hollisters were part of a larger franchise until I discovered a stash of 15 more titles at a yard sale. By then, I was a little older, and I marveled at how all the loose ends of the plots wrapped neatly in 182 or 184 pages like clockwork.

Only recently did I learn that the Hollisters were part of the Hardy Boys/Nancy Drew empire. Their return to the publishing stage in the 21st Century can be seen as a triumph of self publishing, and an object lesson on the importance of preserving one’s intellectual property.

In 1950, when the firm began revamping those books to purge them of the offensive racism that had nearly gotten them axed by their publisher, Grosset & Dunlap, Svenson oversaw that operation, revising titles that he himself and other writers had written years earlier. (I’m not going to delve into the specifics of that revision project; that’s what Prof. Wiki is for.) Franchises such as the Bobbsey Twins, the Hardy Boys, and Nancy Drew have since been revised numerous times to fit those characters into the modern world. Before anyone was thinking of purging James Bond or Hercule Poirot or Willy Wonka, the Stratemeyer Syndicate and the publishers who later acquired their stable of stories routinely updated the old books. It was what you did if you wanted to keep selling. I’d venture to say that anyone who grew up on those books would agree that revising them in the 1950s was probably a good thing.

|

| Andrew Svenson, 1948 photo. (Courtesy happyhollisters.com) |

The Hollisters, who live in the fictional town of Shoreham, consisted of a mom, dad, five kids, a dog, a cat, and—in the later books—a donkey adopted on a trip to Puerto Rico.

|

| (Courtesy happyhollisters.com) |

As they travel the USA and the globe, the Hollisters encounter new cultures and find themselves in the middle of a new (yet always murderless) mystery. For the era, the books were considered educational since they delved into different topics—sign language, braille, coin collecting, new cuisines, foreign languages, just to name a few. The photos Svenson collected on his travels informed the illustrations later created by Helen S. Hamilton.

In 2010, Svenson’s grandchildren re-launched the series as a self-publishing venture, carefully retyping the entire series—1.1 million words—into digital form for the first time, and carefully digitizing the original Hamilton images and covers. One by one, they re-issued the books as ebooks, paperbacks, hardcovers, and eventually audiobooks. They connected with fans via social media, a website, and homeschooling conferences. The final reissued book pubbed last year. Reviewers on Amazon largely celebrate the books as wholesome, and routinely cheer their happy endings.

The Svensons—via The Hollister Family Properties Trust—lucked out by making their own luck. Svenson’s widow wisely renewed the copyrights of all the books, which was necessary at the time. His children and grandchildren were all well-educated, many of them with backgrounds in publishing, radio, marketing, and catalog sales. If there was one family who was not going to lose their father’s legacy, it was this one.

That all said, how well do the books hold up?

I certainly came across language and scenarios that struck me as antiquated. Eleven-year-old Pam Hollister wonders if girls are allowed to enter the kite contest at Sea Gull Beach. Prior to their trip, the siblings mount a pirate play to benefit a local hospital for “Crippled Children.”

In The Indian Treasure, the fourth book in the series, the Hollisters visit the Native American Pueblos of New Mexico. They learn about adobe houses, historic pueblo structures and kivas, turquoise jewelry, the Hispanic culture of the Southwest, chili con carne, and more. That all struck me as truly educational. Svenson researched Pueblo culture by connecting with Popovi Da, a legendary Native American artist, and docents with a famed tour company.

Yet there’s still a moment in The Indian Treasure—just one—where an individual is described as a redskin. When the Hollister kids are playing, their shouts of joy are described as “war whoops.” A lot of their conversation touches on all the “nice Indians” they’re meeting, perhaps implying that there are “bad Indians.”

I could go on, probably, but you get the idea. As I read The Indian Treasure, knowing the history of the Stratemeyer titles, the former children’s editor in me thought, “Wow, this would have been so easy to fix. The book is already 90 percent respectful to other cultures. Why not revise it so it’s perfect for the 21st Century?”

That’s where I had to slap myself and ask myself the question I asked you at the beginning. Books are a snapshot in time. When the author says it’s done, it’s done. Dame Agatha did in fact famously revise the book we now know as And Then There Were None for the American market, eradicating its inherent racism. She was alive to do that work, though her UK publishers changed the UK title in the 1980s, after her death. In the New York Times article I link to above, her great-grandson says the book would have been unpublishable if they hadn’t.

I think that’s the way to go. I mean, this is a series that presents a post-war America where diversity is largely nonexistent. The Hollisters are white kids who live in a largely white neighborhood. But that describes most of the old movies cinephiles celebrate today. Heck, it describes a ton of modern movies and TV programs. As an aside, I’ll note that Svenson did in fact write the first African American mystery series for Stratemeyer, featuring a five-kid family not unlike the Hollisters. I’m tracking down a few of those original volumes to review.

That said, aside from the cultures they visit, the Hollisters don’t ever meet anyone who isn’t white unless the plot necessitates the diverse character’s presence. An encounter with a Native American baseball player in their hometown is the inciting plot point of The Indian Treasure, for example. Changing the plot to “correct” the Native American issue would not fix the overwhelming whiteness. You’d have to revise the entire series.

That brings up a host of questions I don’t feel qualified to answer, or even grapple with. But’ll throw them all at you, because some of you have been at this game longer than I have, and probably can offer some coherent responses.

If it was okay to revise the old Hardy Boys and Nancy Drews, why isn’t it okay to revise Fleming, Dahl, LeGuin, or Christie?

Is it because the Hardy Boys and Nancy Drew aren’t considered great literature?

Because they were written by an ever-revolving team of house writers?

Because they were mystery novels for kids?

What’s really the issue? Are we okay protecting kids from potentially troubling content, but comfortable allowing adult readers to make up their own minds about the content they consume?

How does this connect with banning books?

And while your eyes are still bleeding, let me lob the most important one at you: Why won’t the Willy Wonka slot machine recognize that I’m a huge fan of the Gene Wilder movie, and let me win big time?

* * *

See you in three weeks!

%20websize.jpg)

.png)