Life moves pretty fast. If you don't stop and look around once in a while, you could miss it.

-John Hughes,

Ferris Bueller's Day Off (1986)

As regular readers of my turn in this blog rotation (both of them!*rimshot*) will no doubt recall, my day gig for the past twenty-five or so years has been teaching history at the secondary level. For the past twenty years I have taught solely at the middle school level (and in the same school, no less).

What's more, I have loved nearly every minute of it.

As of this time last week, I had every intention of coming back to this same position in this same school and teaching 8th grade history for the eighteenth consecutive year. The only changes would be a shift in the era taught (from Ancient and Medieval World History to American History, 1790-1920), and a one-year move to teaching part-time as a single-year concession to some on-going health problems (both my own and those of a close family member).

In short I'd be teaching American History (my MA is in 19th century American History) three periods per day, rather than Ancient and Medieval World History five periods per day. At least, that was the plan. And it has been a long-standing precedent in both my building and my district that this sort of part-time schedule is a morning gig, wrapping up around Noon or shortly thereafter, leaving my afternoons free to take care of myself and my family.

And then last Thursday happened.

At 8:58 AM I received an email from my vice-principal informing me that not only would I not be teaching in the morning, but I wouldn't be teaching 8th grade. My building administration had scheduled me to teach three 7th grade classes from 11:19 to 3:20 every day.

What's more, my administrators had made this radical change to my on-going schedule without once doing me the courtesy of consulting me about it. That is just not done.

In fact I had filled out the required end-of-school-year wish-list for the coming year and made it clear that I was only interested in continuing to teach 8th grade Social Studies. Early in my career I had taught multiple subject areas and grade levels in different classrooms over the course of school day. This went on for the first several years of my teaching career-just paying my dues, nothing more, nothing less. As I gained seniority within my subject area and within my building, that changed.

I don't need to tell anyone who has a family member either attending or working in the public school system during the COVID-19 pandemic that the past three years have been some of the most stressful for all concerned in the history of public education. And that stress has taken a toll on my health. Hence my taking a partial leave in the first place.

To say that working a mid-day schedule would do nothing to support my attempts to address my on-going health concerns is an understatement. In point of fact, it would cripple them. As for teaching 7th grade, that too was a minefield.

My district recently changed the 7th grade curriculum to one provided by an education nonprofit. To call it "history" is to misname it. It's barely social studies. Without getting too deep into the weeds on this, I'm a trained historian, published in my field, and cannot, in good conscience, agree to teach this curriculum. Period.

So there are two nonstarters.

Which meant I was suddenly faced with a choice: "What do I do about it?"

I briefly considered reaching out my to building admin to ask why they had done this, and whether there was wiggle room to change it up to something more palatable, something that would work better for me and my needs. I did not consider this option for long.

After all, when I first began to consider taking a partial leave of absence for the coming year, I immediately consulted with my building administration, as a matter of professional courtesy. This was three months ago. When I decided on this course of action two months ago, I also immediately notified my bosses. I was able to confirm this shift in my work assignment had been in place for at least a month by the time I received my career-changing email last Thursday.

That begs the question: why did my bosses not afford me a similar courtesy? I would think at the very least my twenty years' working in this building merited an in-person conversation as soon as the decision had been made, and not simply announced in an email several weeks later.

Draw your own conclusions as to what these actions on the part of my building admin say about my value as an educator within a building I've called my professional home for two decades. I know I certainly did.

So I did the smart thing. I went home and talked it over with the wisest, brightest, kindest person I know. My wife. (Yes, she's all of the above and more, and NO you CAN'T have her. She's all MINE!).

My wife expressed concern for my health (as she had before many times) and for what toll the stress of this new schedule and struggling with this new curriculum might take on me. Her proposed solution was an astonishing combination of love, compassion, empathy, and concern for my well-being.

She suggested I simply expand my leave for next year to a full-time leave. She made the case that we could afford it, and all she asked in return was that I honor my obligations to address my chronic health issues, help my family, and one other thing.

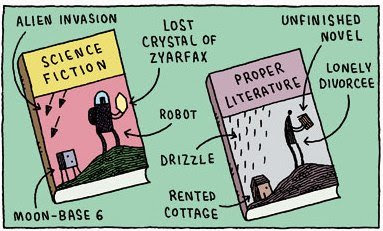

I have to finish my current novel, outline and write another one, and write and publish a yet-to-be-determined number of short stories and novellas.

What writer in his right mind (no cracks, now!) would not take that deal?

So that's what I did.

The next day I informed my principal (a wonderful lady, new to our building this year, but someone whom I very much enjoy and toward who I have not one shred of ill will). Her dismay at my decision frankly surprised me.

I mean, no one talked to me about this. Literally for weeks.

So when she started bartering, trying to keep me on-staff at least part-time, I had to stop her. After all, I didn't do what I did as the first move in a series of negotiating ploys trying to "get what I wanted."

I made a decision. An informed one. And truth be told, as I explained to my principal just last Friday, they did my a favor. Their scheduling me to teach afternoon 7th grade classes forced me to take a good hard look at my plan to work part-time in my building and try to address my health concerns piecemeal.

The realization that I have the option (thanks, again, I hasten to add, to the loving support of the World's Best Wife) to step back and focus on my own needs full-time for at least the next twelve months has been incredibly freeing for me.

And I am beyond grateful. Thanks all over again, honey. I love you more than words can wield the matter.

So that's it. For at least the next year it's get healthier and write, write, write!

See you in two weeks!

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)