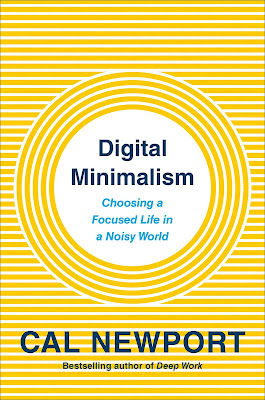

Lanier is a virtual reality pioneer and technologist. I met and interviewed him while writing an article for Discover magazine in 1999. He impressed me then as a profound thinker, but not until I read this book did I perceive him to be a decent, compassionate person and father who is concerned about what social media algorithms are doing to our brains. As he explains it, Silicon Valley has a very high opinion of its social media software, but it is still quite crude, designed primarily to hook us and enrich its creators. Apps distort politics, promote bad behavior, cultivate binary thinking, stoke triggering behavior, and make us cranky. Before reading the book I thought I could simply delete the apps from my phone and just take a break from social media. (I did this one year and was impressed.) An optimist, Lanier believes that the software can be written to be more decent, but he argues that the firms involved won’t change their game until a significant number of people delete their accounts. Big difference.

The Social Dilemma (Netflix, 2020).

The most compelling thing about this documentary is that all the talking heads are people who worked for major firms like Facebook, Google, Twitter, and came to see how destructive their products were. It’s fascinating to hear their arguments for why social media must change—and their fears. The line that gets repeated often: “If you're not paying for a product, you ARE the product.” If you could take back some of your own autonomy, agency, and privacy, wouldn’t you? I also recommend the documentary Fake Famous (HBO, 2021). Journalist Nick Bilton chooses three young people at random and tries to see if he can transform them into Instagram influencers overnight. The secret of his success? Buy them a bunch of bots! It feels like a trivial project and film (lots of fun, lighthearted moments) but it’s scary how many millions of people are playing this pathetic game for real.

Stolen Focus: Why You Can't Pay Attention—and How to Think Deeply Again, by Johann Hari (Crown, 2022).

I wish I had a dime for every time I’ve heard someone say that they just can’t read or finish books anymore. This comment usually comes from longtime readers, who are surprised that they can’t sit still, focus, and blow through a book in a matter of hours, the way they once did. They profess shock and shame, but British-Swiss journalist Hari says none of us are to blame. Our attention spans have been steadily eroded and fractured by 12 forces in modern life, which he carefully distills by interviewing a phalanx of scientists who are studying various aspects of the phenomenon. Yes, he says, social media and smartphones are one reason, but it’s not as simple as deleting your apps or depositing your phone in a time-locked safe. You might enjoy this brief interview with Hari in which he says:

I went away without my smartphone for three months. I spent three months in Provincetown, Mass., completely offline, in a radical act of will. There were many ups and downs, but I was stunned by how much my attention came back. I could read books for eight hours a day. At the end of my time there, I thought, “I’m never going to go back to how I lived before.” The pleasures of focus are so much greater than the rewards of likes and retweets.

Then I got my phone back, and within a few months, I was 80 percent back to where I had been.

Wiley is not a resource, he’s a New York Times Bestselling author of dark literary fiction, a two-time Gold Dagger award winner, and an Edgar finalist. He’s also a friend here in North Carolina. (At the 2015 Edgars, Wiley—far right—had the distinction of wearing a tux more handsomely than Stephen King!) A longtime Twitter user, Wiley deleted his account a couple of years ago, even though he previously enjoyed using the platform to comment on books and the politics of our day. He is in the process of de-platforming entirely from social media, seeking ways to engage with readers via a new creative program, This is Working, launched on his website. I’ve always admired his writing, and his principles. For years, he was the guy we knew who dared to give up his iPhone. Sensing that he was becoming distracted by the device’s bells and whistles, he “down-teched” to an older model flip-phone. I don’t think I could do the same, but I understand the logic behind it.

.jpg)

.jpg)