(This is the final installment of a three-part series on a notorious murder during the reign of King James I of England [James VI of Scotland]. For the first part of this post, with general historical background as well as a fair bit about the victim, click here. For the second part, which deals mostly with the conspirators, click here.)

When is an "honor" not really an honor?

Everyone knows that sometimes an "honor" is precisely that. A great occasion for the honoree, and the sort of thing to be welcomed–if not outright eagerly anticipated– when it comes your way. Oscar nominations. Getting named to the board of a prosperous Fortune 500 company. Making the New York Times Bestseller list (I should live so long!).

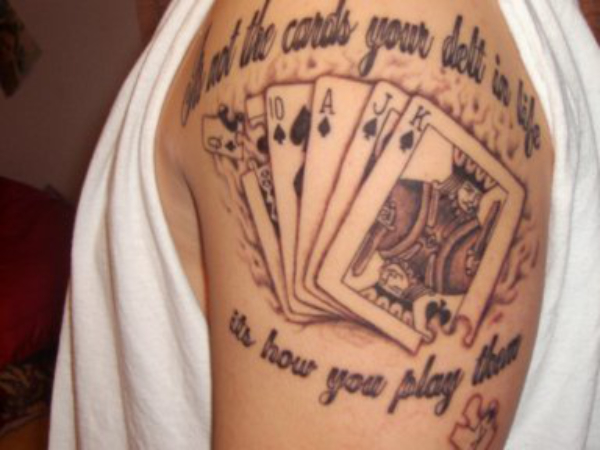

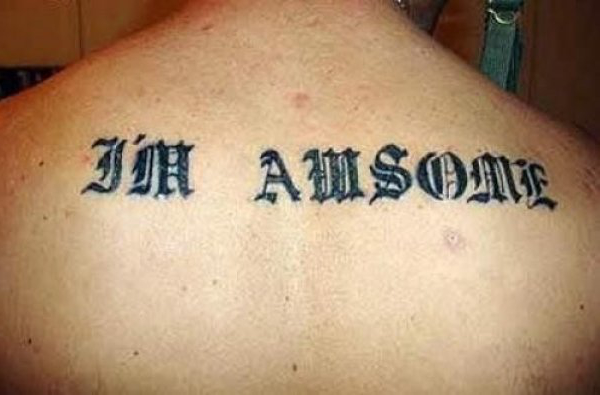

Not always easy to quantify, but like the late, great Supreme Court justice Potter Stewart once said of pornography, "I know it when I see it." The same is also true of the kind of thing frequently called an "honor" when it really isn't.

|

Here's one example

|

And even worse than this type of infamous "non-honor honor" is the sort of honor that could be hazardous to your health. In an example from American history, the 54th Massachusetts Infantry, first black regiment in the United States Army, received the "honor" of leading the charge during an attack on rebel fortifications at Fort Wagner, South Carolina.

Led by their heroic commander, one Colonel Robert Gould Shaw, the 54th did itself proud, spearheading the Union charge into the teeth of murderous cannon fire, in an attempt to take the strategically important fort situated on an island in Charleston Harbor.

But the net result? The 54th Massachusetts Infantry numbered six hundred men at the time of the charge. The regiment suffered nearly a fifty percent casualty rate in this single action alone (two hundred seventy-two killed, wounded or missing)! Among the dead was Shaw, the colonel who led the way.

When it's an offer to serve as ambassador to Russia!

While not necessarily a death sentence, a 17th century example of an "honor" along these lines was serving as an ambassador to Russia. Especially during the early part of the century, when Russia was pretty much the "Wild West" (without the "West" part) of Europe. Anarchy. Lawlessness. A devastating famine that began in 1601 and lasted for years afterward. Invasion and extended occupation by Polish armies, culminating in a teen-aged Polish-Swedish nobleman briefly taking the throne in 1610!

By February of 1613, things had gotten a little better, with the Russians kicking the Poles out and electing a new (Russian-born) tsar, Mikhail, who established the Romanov dynasty. Barely twenty, Mikhail faced a long, grinding battle getting Russia's nobility to mind their manners and unite behind him in anything other than name. So even though there was a new sheriff in the Kremlin (and if his coronation portrait is any indicator, one with superb taste in spiffy red boots!), there was still plenty of lawlessness, crime, war, famine and pestilence to go around.

Even with the Poles gone, Russia was an impoverished, backward country on the periphery of what most Europeans considered civilization. For government functionaries such as Overbury, it was the type of diplomatic posting where careers went to die.

So how did he come to be the recipient of such a signal "honor"?

What happens when you piss off a rival and that rival has the queen's ear.

As mentioned previously, Overbury seems to have consistently overestimated his own cleverness, andsystematically underestimated that of nearly everyone around him. He had expended a great deal of time and effort steering his pretty boy puppet Robert Carr into King James' orbit so as to profit by a successful pulling of Carr's strings. When the king began to entrust Carr with a number of duties involving fat salaries attached to a slew of confusing paperwork (Carr was pretty but not too bright), of course Carr relied heavily on his friend and mentor Overbury to help out with the details. Overbury in turn took his own considerable cut. Pretty standard stuff, where court preferment was concerned.

All that changed when the king's favorite minister Robert Cecil, earl of Salisbury died, and a power vacuum opened close to the throne. Salisbury oversaw James' foreign policy, and with his death the king saw an opportunity to begin to set that policy himself, as long as he had someone along for the ride who could handle the intricacies of diplomatic language (and paperwork). He decided that his favorite Robert Carr was perfect for the gig.

Of course Carr was not remotely suited for such work. But his mentor Overbury was.

With Carr's elevation to his new role there were people lining up to try to win influence with him, and through him, with the king. This included members of the already powerful and well-connected Howard family. Namely Henry Howard, earl of Northampton and his niece, Lady Frances Howard, already married in a teen-aged and allegedly never-consummated hate-match with the young earl of Essex.

As Overbury had done with Carr, placing him in King James' path, now Northampton did to Carr, placing his still-married and barely into her teens niece in Carr's. Her tender years notwithstanding, Lady Frances had already acquired a reputation for bed-hopping, and while Carr seemed capable of wrapping a king around his little finger, he seems to have been no match for Frances' feminine wiles.

The two were soon openly consorting, and there was talk of marriage after first seeking an annulment of Frances' marriage to Essex, on the grounds of non consummation. (The earl detested his new bride nearly from the moment he met her and fled on a tour of the continent rather than sleep with her. And he stayed away for a good long while afterward!).

Overbury was furious at being frozen out of the lucrative gig of pulling Carr's strings, and published a widely-read poem pretty effectively slandering Lady Frances. He had made a powerful enemy.

What's more, this enemy was a favorite of the queen. She managed to prevail on Queen Anne to convinceher husband the king to offer Overbury the "honor" of serving as His Majesty's man in Moscow.

Now Overbury found himself outfoxed. If he accepted the posting, he'd be away from court, with no influence and no money. To the people of Jacobean England, Russia was only slightly closer to home than the New World, which was to say one step closer than the moon!

However, to refuse such an offer of appointment was flat-out dangerous. Such refusal could be taken as an insult, and history is replete with examples of how well royals tend to take insults from those ostensibly in their service. (Newsflash: it ain't lying down!)

Overbury's thoughts along these lines are not recorded. And there's no way of knowing whether he seriously considered the possibility that the choice before him could possibly wind up being between a trip to Russia or a trip to the Bloody Tower. Regardless, he chose to refuse the "honor" of serving as English ambassador to Russia, and apparently managed to come off as so high-handed that in April 1613 an infuriated King James had him tossed into the Tower for his trouble.

By September, Overbury was dead.

Ten days later Lady Essex received her wished-for annulment, over Essex's protestations that he was not, in fact, impotent, as the papers requesting the annulment claimed. Within a couple of months, Lady Frances and Robert Carr, now no longer earl of Rochester, but "promoted" to an even more plumb title with vastly more substantial holdings as earl of Somerset, were married.

That might well have been the end of the story. But Robert Carr was an idiot, and it quickly became clear that he was now as much the Howards' puppet as he had earlier been Overbury's. Plus, the king was fickle in his affections where his favorites were concerned, and apparently within a year or so, Carr began to lose his hair and his looks. James soon tired of his pet earl, and let it be known to certain influential members of his inner circle that he would welcome an excuse to be shut of him, so he could focus his attentions elsewhere (namely George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham).

And that was when rumors began to surface about Carr's frequent visits to the Tower to see his erstwhile friend and mentor Overbury in the months preceding his death. And of Carr's possible connection with the gifts of possibly tainted food and drink a certain jailer pressed upon the unfortunate man.

The Investigation

Whispers of "poison" were nothing new during the reign of James I. Invariably when anyone of any importance died quickly and without violence, some gossip, somewhere began to murmur in the ears of friends that the circumstances certainly seemed suspicious. And as much as James wanted to be rid of Carr, the last thing he wanted was a scandal. So he set his two brightest advisors to work on the investigation, ensuring it was handled right from the start.

These two were none other than the greatest legal minds of the age. Two great names that survive even today: Sir Francis Bacon and Sir Edward Coke.

The first thing they did was have Overbury's corpse exhumed and subjected to an autopsy. He was indeed found to have been poisoned. Not by food, or drink, it turns out, but by a combination of emetics and enemas.

Overbury's jailer and the lord lieutenant of the Tower were immediately confined and questioned. It all came out in their confessions and the confessions of those they named as co-conspirators.

Apparently Lady Frances and her uncle the earl of Northampton dreamed up the scheme to have Overbury dispatched in a manner which might not look suspicious, and pressed her dupe of a husband into service, getting him to visit his "friend" Overbury regularly, and impress upon him the only way out of the Tower was through touching the heart of the king and moving him to pity at Overbury's lowly state.

Confinement did not agree with Overbury, and he was already ill. But a combination of emetics andenemas would help make him seem even more piteous and enfeebled, certain to prod James into an act of clemency, Carr argued. Overbury, desperate to escape the Tower, agreed to this course of action.

In furtherance of the Howards' plan, the Tower's lord lieutenant (the government official overseeing the operation of the Tower) was removed in favor of a notably corrupt one named Helwys (recommended by none other than the earl of Northampton, to whom he paid a customarily hefty finder's fee), who in turn assured that a jailer named Weston agreeable to Lady Frances' plan was placed in position to oversee Overbury's "treatments."

Lady Frances' connection to the plot was laid bare by the confession eventually wrung from her "companion," a seemingly respectable physician's widow named Anne Turner. In reality Turner was anything but.

While her husband was still alive Anne Turner carried on a prolonged affair with a wealthy gentleman, and bore him a child out of wedlock. After her husband's demise she "made ends meet" in part by running a secret red light establishment where couples not married to each other could go to have sex. She had also served as her deceased husband's assistant on many occasions and possessed some skill with chemicals–especially poisons. She quickly developed a black market business selling them to many of the "wrong people."

So when her employer Lady Frances came to her seeking help, Anne Turner was more than willing to assist. Together with an apothecary she knew and worked with, Turner came up with several doses of emetics and enemas laced with sulfuric acid. Weston in turn administered these to an unsuspecting Overbury, who soon died.

The Outcome

Possessing not much in the way of either money or influence, the quartet of Turner, Weston, Helwys and the apothecary (whose name was Franklin) were quickly tried, convicted, condemned and hanged.

The earl and countess of Somerset, who did possess both money and influence, were immediately arrested and thrown into the Tower. The earl of Northampton only escaped a similar fate by having had the good timing to die the previous year.

The resulting scandal, far from merely ridding the king of a tiresome former favorite, caused James no end of embarrassment. He repeatedly offered to pardon Carr in exchange for a confession to the charge of murder.

For her part, Lady Frances quickly admitted her part in Overbury's murder. Carr, however, insisted ever afterward that he knew nothing of the plot (given his demonstrated lack of smarts, hardly difficult to believe that he was little more than the dupe of his extremely cunning wife). The earl and his wife were tried and eventually convicted on charges of murder and treason. Obviously concerned that Carr might implicate him in the murder and no doubt also nervous about what Carr might say about the nature of their personal relationship, James let them languish in prison for seven years, eventually quietly pardoning both the earl and the countess, and equally quietly banishing them from court.

Apparently the bloom came off the rose for this star-crossed couple during their long confinement, and their burning passion cooled into a dull hatred. If Carr's protestations of innocence are true, it stands to reason that the revelation of the part she played in killing his friend and mentor Overbury may have had something to do with his seeing her in a different light.

The next ten years after they were pardoned in 1622 were spent quietly loathing each other on Carr's estate in Dorset, far from the pomp of James' court in London. Lady Frances died aged 42 of cancer in 1632. Carr followed her to the grave in 1645.