They had come that night to hear the author Erik Larson speak about his latest book, The Splendid and the Vile, about the leadership of Winston Churchill during the Blitz of 1940-1941. Larson, as you probably know, is the acclaimed, bestselling author of numerous works of narrative nonfiction, probably most famously The Devil in the White City, but also Isaac’s Storm, Dead Wake, In the Garden of Beasts, and so on.

|

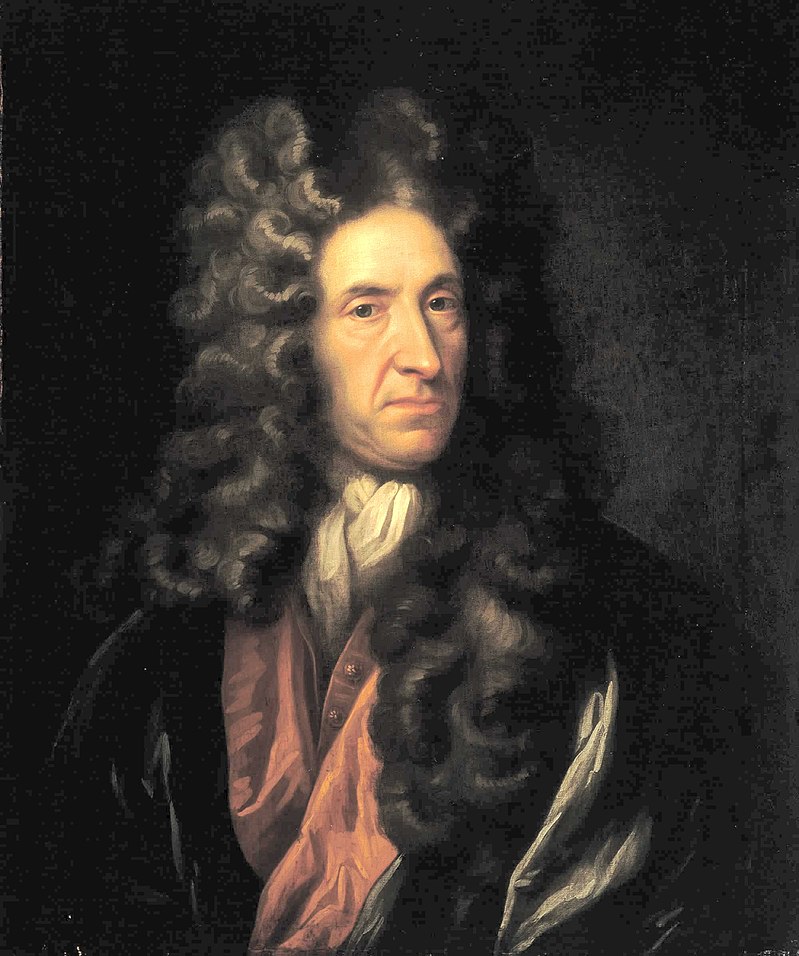

| Erik Larson in conversation with Denise Kiernan. |

When I studied journalism in college, my professors sang the praises of such New Journalism writers such as Gay Talese, Tom Wolfe, Joan Didion, Jimmy Breslin—writers who were reporters first, yet used the techniques of fiction to make their true stories read as engagingly as made-up ones. I admired all those writers when I was in my late teens, and even today I never tire of hearing how they organize their information.

That’s why I was there to hear Larson. Well, that’s not precisely true. My wife, Denise Kiernan, an acclaimed, bestselling narrative nonfictioneer herself, was interviewing Larson that night, and she insisted that a) I attend, b) sit in the front row, and c) take lots of pictures. In our small city, Denise does a lot of “in conversations with” various authors, and as a result I’ve become the world’s worst photographer of book events. In my defense, authors hardly move when speaking about books, so how can we expect the resulting photos to be dramatic? I happily found that Larson does love to gesture. Look at those hands!

Some takeaways from that night, and from his book, which I’m currently reading.

- Unlike novels, nonfiction books are sold on the basis of a book proposal, which can run anywhere from 25 to 100 pages. This is primarily a sales document, meant to convince editors to act now! and buy the book already! With 9 million books sold worldwide, Larson can now probably get a book deal on the basis of a 30-second phone call to his editor. But he insists on writing a full proposal, to be absolutely certain the book he’s proposing has a beginning, middle, and end.

- Just before Larson's The Devil in the White City was published in 2003, Larson was absolutely convinced that his career was over. Why? He didn't think people would like/understand/appreciate the new book because there was no true link between the two different components of the story. That is, on one hand you had the diabolical machinations of Herman Webster Mudgett (aka H.H. Holmes), a serial killer. On the other hand you had the grandeur, innocence, and raw American promise of the 1893 World's Fair. Both true-life stories happened at the same time in Chicago. Larson thought they would make a good combo, but he was worried that readers (and perhaps critics) wouldn't accept the premise of a story that leaped between the two. He needn't have worried. So far as I'm able to determine, that book remained on the New York Times bestseller list for at least 366 weeks.

- Over the years, Larson has developed a sixth sense about the telling details that he and lay readers love. Just as we learned in The Devil in the White City that the Ferris Wheel, which first debuted at the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago had “consumed 28,416 pounds of bolts in its assembly,” we learn that Churchill—at heart a government employee whose personal income did not permit him to spend extravagantly on alcohol for his guests—nevertheless ensured that Chequers, the government-funded estate he used for his weekend retreats, was in turn amply stocked at government expense. One liquor order, Larson tells us, consisted of 36 bottles of Amontillado, 36 bottles of white wine, 36 bottles of Fonseca port, 36 bottles of claret, 24 bottles of whiskey, 12 bottles of brandy, and 36 bottles of champagne. The rules imposed by the British government were that Churchill could only serve this booze to foreign dignitaries, and his staff had to keep strict details on who had consumed what. Records would be audited every six months.

- Speaking of big numbers: In the history of WWII literature, there have been approximately 18 quintillion books written about Churchill. To ensure that he was coming up with something fresh about the man, Larson initially limited himself to reading only a few biographies about Churchill. Then he carefully set aside those volumes, and dug into the archives firsthand to find “his”—that is, Larson’s—Churchill.

- When he’s researching in archives, Larson will photograph records, if permitted, with his smartphone. Images of primary sources, especially letters written in a spidery hand in fountain pen ink, are often hard on the eyes. But digital images can be later adjusted on a computer, shifting, say, the color contrast, and thus making them easier to read.

- Before he writes, Larson spends countless hours slotting all the dates of each piece of data—official reports, personal letters, etc.—he’s found into a timeline of sorts that allows him to craft more dramatic scenes. Thus: When Churchill was here doing this, his daughter was here doing that. Those timelines might run 80 pages in length.

- The writer in me especially loved reading how Churchill insisted his underlings learn to write better reports. Quoting from the book:

“Let us have an end to phrases such as these,” [Churchill] wrote, and quoted two offenders:

“It is also of importance to bear in mind the following considerations…”

“Consideration should be given to the possibility of carrying into effect…”

He wrote: “Most of these woolly phrases are mere padding, which can be left out altogether, or replaced by a single word. Let us not shrink from using the short expressive phrase, even if it is conversational.”

The resulting prose, he wrote, “may at first seem rough as compared with the flat surface of officialese jargon. But the saving of time will be great, while the discipline of setting out the real points concisely will prove an aid to clear thinking.”

- Lastly, Larson observes that Churchill’s wartime speeches to the British public adhered strictly to a kind of formula. First, he transparently laid out the dilemma all Britons were facing in clear, unvarnished terms. Then he enumerated reasons for hope, reasons for citizens to keep fighting the good fight, and why their efforts might actually turn the tide. And he always closed with a memorable, rhetorical flourish that stirred the hearts of all listeners and moved them to action.

Hearing Larson speak of this, and later reading his descriptions of Churchill’s speeches in the book, moved me deeply and left me longing for such a leader, should such dark times ever leap to the fore again.

Postscript:

A few nights after we last saw Larson, he texted my wife to say that the remainder of his book tour had been canceled, as had the tours of so many authors. Larson's book still shot to No. 1 on the NY Times bestseller list for hardcover nonfiction, as many of his previous books had, but the independent bookstores that were planning to host him no doubt lost out on many of those sales. This is the current crisis facing countless authors and bookstores.

To that end, my wife is on the lookout for ways to conduct her previously scheduled "in conversation" book events virtually. What software are people using to do this effectively? We've heard people sing the praises of everything from FB Live to Zoom to Crowdcast, and so on. Kindly let me know your experiences in the comments. Be well, and take care of yourselves.