So how to put the Advanced into the Advanced Workshop? beyond simply admitting students who are already bringing as much skill as enthusiasm to their work?

Back over the holidays—just before Christmas, then just after the new year—a couple of questions online got me thinking about specific aspects of short story writing, how I teach students to write them, and how I write them myself. First, Amy Denton posted a question on the Sisters in Crime Guppies message board: “Depending on the length, is there enough room in a short story for a subplot?” Responses ranged widely, and the discussion was extensive, but with no clear consensus.

Then, reviewing a couple of short stories from a recent

issue of Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery

Magazine, Catherine

Dilts wrote, “A rule beginning writers encounter is that multiple points of

view can't be used effectively in short stories…. How does telling a tale

through more than one narrator work?” A story by fellow SleuthSayer Robert

Lopresti, “A Bad Day for Algebra Tests,” offered Dilts one example of how well

that approach can succeed.

Then, reviewing a couple of short stories from a recent

issue of Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery

Magazine, Catherine

Dilts wrote, “A rule beginning writers encounter is that multiple points of

view can't be used effectively in short stories…. How does telling a tale

through more than one narrator work?” A story by fellow SleuthSayer Robert

Lopresti, “A Bad Day for Algebra Tests,” offered Dilts one example of how well

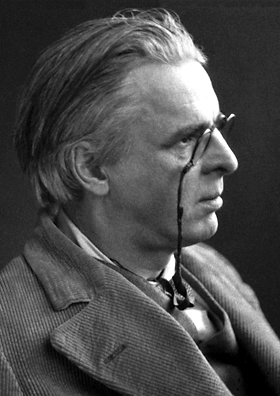

that approach can succeed.Another of our SleuthSayers family—Barb Goffman, a master of the short story herself—has a great piece of advice for writers: namely that the short story is about “one thing.” (I’ve heard other writers repeat her words and I've repeated them myself down the line.) And our good friend and former SleuthSayer B.K. Stevens and I were both big fans of Poe’s ideas about the “single effect” in the short story, that everything in a tale should be focused toward one goal, toward having one effect on the reader: "In the whole composition," Poe wrote, "there should be no word written, of which the tendency, direct or indirect, is not to the one pre-established design."

When I’ve taught workshops on short story writing, I often put Poe’s words and Barb’s on back-to-back PowerPoint slides, emphasizing the resonance between the two points. (Both authors are in good company!) And several assignments in my classes are geared toward these ends. I have students write a six-sentence story as a first day exercise, for example. When they turn in their full drafts, class discussion begins with charting out the escalation of rising conflicts (Freytag’s Triangle, not to be too academic!) and ferreting out anything that doesn’t fit. And as we move toward revision, I have them reduce those drafts down to three sentences (three sentences of three words each!) to crystallize their understanding of the story’s purpose and arc.

Focus on the “one thing” is always the goal. Efficiency along the way, that’s key. “A short story is about subtraction,” I tell them. “Cut away anything that doesn’t belong.”

And yet…

Many of the stories that have stuck with me most vividly over the years are those that maintain that focus on “one thing” and yet also stretch further beyond it too: multiple points of view, intricate time shifts, a braiding together of several other elements in addition to whatever the central plotline might be. Here’s a sample of some favorites just off the top of my head:

- “All Through the House” by Christophe Coake, with multiple points of view and a reverse chronology

- “Ibrahim’s Eyes” by David Dean (one more SleuthSayer!), balancing two time frames with storylines that each inform the other

- “The Babysitter” by Robert Coover, a wild story in so many ways, veering off into fantasies, desires, and what-ifs while still circling back to what actually happened (I think)

- “Billy Goats” by Jill McCorkle, which is more like an essay at times, drifting and contemplative—in fact, I’ve passed it off as nonfiction in another of my classes

- “How I Contemplated the World from the Detroit House of Correction and Began My Life Over Again” by Joyce Carol Oates (full title of that one is “How I Contemplated the World from the Detroit House Of Correction and Began My Life Over Again—Notes for an Essay for an English Class at Baldwin Country Day School; Poking Around in Debris; Disgust and Curiosity; a Revelation of the Meaning of Life; a Happy Ending” so you can see how plot and structure might be going in several directions)

(All of these are about crimes—though some of them would

more likely be classified mysteries than others. (Don’t make me bring up that

“L” word.))

Even looking at my own fiction, I find that I’ve often tried

to push some boundaries. My story “The Care and Feeding of Houseplants,” for

example, alternates three different points of view, three characters bringing

their own pasts and problems to bear on a single dinner party—with a couple of

secrets hidden from the others, of course. Another recent story,

“English 398: Fiction Workshop”—one

I’ve talked about on SleuthSayers before—layers several kinds of storytelling, centered around a

university-level writing workshop, with a variety of voices and tones in the

mix. (The full title of the story makes a small nod toward Oates in fact: “English

398: Fiction Workshop—Notes from Class & A Partial Draft By Brittany

Wallace, Plus Feedback, Conference & More.”) And a story I just finished revising

earlier this week, “Loose Strands,” also has three narrators, an older man and

two middle school boys, their stories coming together around a schoolyard fight,

colliding, combining, and ultimately (at least I’m aiming for this)

inseparable.

As I commented in the discussion forum in response to Amy Denton’s question: “I often try to think about how the characters involved each have their own storyline—the storylines of their lives—and how the interactions between characters are the intersections of those storylines. And I challenge myself to try to navigate a couple of those storylines as their own interweaving narrative arcs, each with its own resolution, where somehow the end of the story ties up each thread.”

Maybe the idea of multiple points of view and subplots

collapse together in several ways, thinking again of Catherine Dilts’ review of

Rob’s story and of another, “Manitoba Postmortem” by S. L. Franklin. And in my workshops

at Mason, I’ve used Madison Smartt Bell’s terrific book, Narrative Design, to explore modular storytelling, experimenting

with shifts in chronology and points of view, layering several strands of story

together. Some students catch on quickly, love the opportunities provided by

this kind of storytelling. (But as beginning writers, it’s important—as I

stressed—for them to build a firm foundation first in storytelling elements,

techniques, and more straightforward structures. Walk those stepping stones

first.)

So in thinking about the discussion Amy’s question sparked and the review Catherine wrote and my teaching and my writing, I find myself pulled in a couple of different directions: committed to Barb’s (and Poe’s!) ideas about the short story, always striving to stick as close to the core armature of a story as I can, but also occasionally testing those boundaries, pushing them to see what happens.

So in thinking about the discussion Amy’s question sparked and the review Catherine wrote and my teaching and my writing, I find myself pulled in a couple of different directions: committed to Barb’s (and Poe’s!) ideas about the short story, always striving to stick as close to the core armature of a story as I can, but also occasionally testing those boundaries, pushing them to see what happens.

So… some questions for readers here and for my SleuthSayer buddies as well: How would you answer the questions above about subplots and multiple points of view? How closely do yourself stick to the idea of the single-effect in the short story—to the story being about one thing? How do you balance those demands of the form with interests or ambitions in other directions?

As for my advanced fiction workshop ahead… I’m still going to keep the students concentrating on the “one thing” that’s the core of their stories—focus and efficiency always, and credit again to Barb. But as much as a workshop should be about learning the rules and following best practices, it should equally be a place to take some risks and have some fun. And so I also want them to play with structure and storytelling, to stretch their talents wherever they want, and to see where it takes them.

Any suggestions for the course—those are welcome too!