If a story uses a first person narrator, the most important action in that story is the

telling. The narrator arranges the people and events in a way that serves his purpose. Since he has a stake in the story, sometimes he cheats. That's where the fun begins.

Many of the classics gain their power from the irony of a dissembling story-teller. Lockwood, the secondary narrator of

Wuthering Heights, is too conceited to understand that Nelly Dean passes the buck in her tale of Heathcliff and Catherine's star-crossed love. Through negligence or prejudice, she causes every tragedy in the book and blames Heathcliff, whom she admits she loathed at first sight.

Dickens's

Great Expectations thrives because Pip believes that Miss Haversham is polishing him to be worthy of Estella. By the time he understands that Magwitch is his real benefactor, he also realizes that Estella is a miserable woman who would be a horrible match for him.

Critics have argued about Henry James's

The Turn of the Screw since its serialization in 1898, and James did little to settle the argument, calling his story merely a "pot-boiler to catch the unwary." His prologue (He almost never used a prologue) shows us a series of narrators who are either biased, lazy, or irresponsible, and the story seems to be an exercise in covering everyone's tush. Is it a ghost story, or did the governess hallucinate the shades of Miss Jessel and Peter Quint? The visions first appear when she daydreams about the handsome master who hired her under strange circumstances, so I tend to side with the Freudians even if they do get heavy-handed. I used to love assigning this story in my honors American Lit classes, especially those who had read Shakespeare's

A Midsummer Night's Dream the previous year and picked up on the allusion to Peter Quince, the rude mechanical who wrote the hilarious play they perform at the end. Musician Quince Peters, who appears in my two novellas with Woody Guthrie, comes from the same source.

The danger of using irony is that readers may not understand. Contrary to increasingly popular mis-reading,

Huckleberry Finn is NOT a racist novel (for that, I suggest

Uncle Tom's Cabin, which portrays the black characters as docile and stupid, more like Labrador retrievers than people). Huck has been raised by a white-trash drunk and he repeats what he's heard about black people all his life. At the same time, he shows us that Pap, Tom, Boggs, Sherburn, the Grangerfords, the Shepherdsons, and the King & the Duke are lazy, greedy, stupid, violent, dishonest, or most of the above. Jim, on the other hand, is brave, loving, loyal, honest, and patient.

Never trust what someone tells you if he shows you something else.

If you write mysteries, the unreliable narrator should be near the top of your bag of tricks. Agatha Christie showed how far you can take this idea in

The Murder of Roger Ackroyd (1926). You don't have to go as far as Dame Agatha, but since people lie in mysteries, why deprive the narrator of so much fun?

Remember, you have to let the reader understand that something is rotten in the State of Denmark. A careless reader won't catch on (so much the better), but if you play fair and suggest along the way that narrator X spins more than bottles, you have lots of possibilities.

So, how do you play fair?

One way involves having the narrator say right up front that he prevaricates. In Kesey's

One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest, Chief Bromden is a paranoid schizophrenic in a mental hospital. He ends the first chapter by telling us, "It's the truth, even if it didn't really happen."

How much clearer can you get?

Holden Caulfield is a direct literary descendant of Huck Fin and a close relation to Chief Bromden. It still surprises me how many readers of

Catcher in the Rye miss that Holden delivers his narration to a therapist after he's had a nervous breakdown.

Mary Katherine Blackwood, the narrator of Shirley Jackson's underappreciated

We Have Always Lived in the Castle, is almost as crazy as Chief Bromden, but not as straightforward. "Merricat" tells us on page one that she's often thought she should have been a werewolf and that she likes Richard Plantagenet and the death's-head mushroom. We see her obsessive rituals to ward off "trouble," too. She lives with her sister Constance and her uncle Julian; the rest of the family died from eating sugar laced with arsenic on their strawberries. The small town shuns the family because they believe Constance evaded prison because of insufficient evidence. It's nearly the end of the book when those townsfolk trash the sisters' home and Merricat snarls, "I will put death in their food and watch them die." Constance says, "The way you did before?" and Merricat answers, "Yes."

She hasn't lied to us before about who poisoned the sugar. The subject simply hasn't come up in conversation. By the time it does, we've had ample opportunity to see that Mary Katherine Blackwood has more issues than the archives of the

New York Times.

Gillian Flynn is equally clear in

Gone Girl. Early in the book, Nick Dunne starts counting the lies he tells other people. This implies that he lies to us, too. Sure enough, when the police and Amy's parents call him out on various inconsistencies, he admits the truth...eventually. What makes the book so powerful is that Amy, the missing wife, lies even more than Nick...and even more skillfully.

Sometimes, the narrator shows you subterfuge without actually saying he lies. Chuck Palahniuk gives us a huge disconnect two page into

Invisible Monsters. The macabre tableau involves Edie Cottrell's wedding reception--and Brandy Alexander bleeding out at the bottom of the stairs from a shotgun blast. Palahniuk's scene is horrific because it's so specific. Then the narrator shows her true colors: "It's not that I'm some detached lab animal just conditioned to ignore violence, but my first instinct is maybe it's not too late to dab club soda on the blood stain."

He's even clearer in

Fight Club. 200 words into the story, he says, "I know this because Tyler knows this." Think about it. He repeats the comment throughout the book, too. That's fair.

Some narrators don't deliberately lie, but their background cause a bias that clouds their vision. I've mentioned Huck Finn, but think also of Nick Carraway, narrator of

The Great Gatsby. Nick tells us his family is wealthy. His unconscious bias against the poor explains his letting Gatsby take the blame even though they both know Daisy drove the car that killed Myrtle Wilson. It's worth pointing out that Nick, who tells us he's the most honest person he knows, has two affairs during the book and came east to avoid marrying the woman he seduced back home.

Never trust what a character tells you if he shows you something else, remember?

In

The Perfect Ghost, Linda Barnes shows us apparently agoraphobic Emily Moore, who mourns the death of her writing partner, killed in what might not have been an accident. At the same time, she starts sleeping with the famous director she and her partner were interviewing so they could write his biography. It may not be dishonest or unethical exactly, but it's poor enough judgment to make us examine the rest of her story more carefully.

Barnes, Flynn and Fitzgerald all use flashbacks, which delay the revelations because an altered chronology puts more pages between the contradictory details so readers are less likely to notice them. I generally avoid flashbacks, but nothing is off-limits if you do it really well. All three of these writers do it really well.

Another way to justify an unreliable narrator is to make him dumb or naive. Ring Lardner's short story "Haircut" (1926) features a barber telling a stranger about the events in a small Midwestern town. The story lasts as long as the customer's haircut, but Whitey the barber is too thick to understand how the people and events he describes fit together. By the end of his story, we understand that a murder has been committed. We know who did it, how, why, and that he will get away with it, too. Great stuff. And the unreliable narrator is the only way to make the story work.

Lardner's tale inspired my own story "Little Things." The two main characters are a bright eight-year-old boy and a shy six-year-old girl who meet when their respective single parents bring them to a miniature golf course. Amy lacks the wider knowledge to know that her experiences are not "normal," and Brian is too young to grasp the significance of what she tells him. Amy's mother and Brian's father are wrapped up in each other and don't even hear the little girl's revelations.

Everybody lies. But first person narrators do it better.

Trust me.

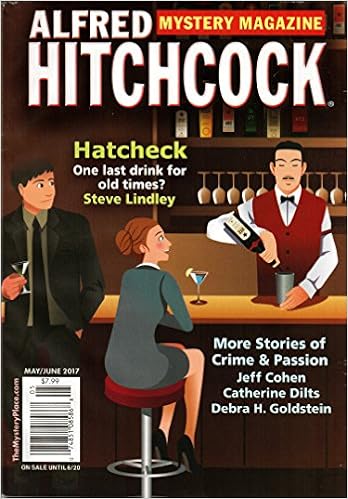

The story of an insurance investigator who steals from the company’s clients, “A Matter of Policy,” my third appearance in Mike Shayne (February 1985), was also first submitted to several men’s magazine. After rejections from Hustler, Playboy, Gem, Buf, Cavalier, Gallery, and Swank, I stripped out 600 words of graphic sex and saw the new version rejected by The Saint Magazine and Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine before acceptance by Mike Shayne on November 11, 1984. Unlike the postcards I received for the first two acceptances, this one came typed at the bottom of a rejection for another story. (The rejected story, “All My Yesterdays,” finally saw publication in Suddenly V [Stone River Press, 2003] and, in 2004, earned a Derringer Award for Best Flash.)

The story of an insurance investigator who steals from the company’s clients, “A Matter of Policy,” my third appearance in Mike Shayne (February 1985), was also first submitted to several men’s magazine. After rejections from Hustler, Playboy, Gem, Buf, Cavalier, Gallery, and Swank, I stripped out 600 words of graphic sex and saw the new version rejected by The Saint Magazine and Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine before acceptance by Mike Shayne on November 11, 1984. Unlike the postcards I received for the first two acceptances, this one came typed at the bottom of a rejection for another story. (The rejected story, “All My Yesterdays,” finally saw publication in Suddenly V [Stone River Press, 2003] and, in 2004, earned a Derringer Award for Best Flash.)