by Leigh Lundin

Saturday, six in the morning. My original article was queued to publish at midnight, but ignoring three tragic events in Orlando doesn’t seem right. I'll talk about one of those events today.

I happened to be out of town when the tragedies hit. Thanks to today’s global news, friends in South Africa sent me links in the early morning hours before my own news feed picked up the shootings. Other out-of-state friends sent condolences as television news lit up with the sun and the death count grew: perhaps more than a dozen killed, then twenty, then forty-something, and finally an even fifty.

Crossed Swords

My first thought when I heard a gay club was attacked was of The Parliament House, a huge night club and resort complex two blocks south of my offices and not far from GLAD, the Gay-Lesbian Alliance. At the moment, The Parliament House’s marquee reads “We are Pulse– Unbreakable.”

My typing fingers try to attach the word ‘notorious’ to Parliament House, the adjective most used by acquaintances, but it occurs to me that it’s probably not notorious to its patrons. An establishment running that strong for more than four decades obviously has something going for it.

The carnage is inconceivable. One shocked resident reported losing seven friends at the Pulse, another more than two dozen. Losing one friend is awful but losing seven or twenty-seven?

A picture emerges not of a religious attack but of a gay hate crime or likely a gay self-hate crime. Reports conflict whether the shooter appeared on gay dating sites, but locals say Mateen, the perpetrator, attended gay clubs in Orlando. Those in the know say Mateen was troubled but not fanatically religious nor had contact with Daesh/ISIS. Police think he donned the mantle of ISIL to gain additional notoriety and as a way of justifying his crime.

Crossed Paths

In writing this, I’ve repeatedly cut out paragraphs that inevitably lead to political positions, but during 9/11, I had my own little encounter with Islam. At the time of the World Trade Center attack, I happened to be renting to a Saudi Arabian tenant. He wore traditional dress and he had a couple of other Muslim friends. They shared shawarma with me, perfectly seasoned, a kind of sandwich I hadn’t had in years.

I needed to make repairs, involving drills and saws. When it came time for prayers, they welcomed me to continue, but I couldn’t– I hadn’t been taught that way. I asked if I might observe and afterward, they explained the significance of small gestures such as angels on the shoulders.

After the 9/11 attackers were identified as Muslim, my tenant was afraid to stay. Although I made it clear he was in good standing with me, he flew home to Riyadh. His being a Muslim wasn't a source of conflict but of communication. He was a good man, a kind person. He gave me a parting gift; I can’t think of another tenant who’s done that. But he was right– some fools would have made his life difficult if not dangerous.

A Case in Point

A few months following 9/11, I was called to jury duty in a criminal trial. An Iranian student was accused of assaulting a girl at Downtown Disney, the entertainment complex originally called The Village, then the West Side, and now Disney Springs. The local State Attorney’s office, apparently considering the case a slam dunk, assigned not just their B-team, but recruits who looked fresh out of college.

The prosecution put on the cop who took the report and made the arrest, then a friend of the victim who said she kind of, sort of witnessed the incident, and finally the victim herself, a striking blonde who proved reluctant in the extreme to testify.

While stopping short of admitting she and the accused were dating, she said they’d had an argument. She’d slapped him and drinks were spilled or thrown in faces. Then presumably he slapped her. No, no.

The defense paraded a number of friends as witnesses who saw and heard nothing, but of course they couldn’t prove a negative. The notion of an alcoholic-fueled spat by clandestine lovers couldn’t be avoided, the proverbial elephant in the room.

We, the jury, identified two problems with the case. First, the alleged victim initiated the incident and struck him first. That troubled us. But we noticed something the lawyers hadn’t. In demonstrations, the witness and victim indicated the boy had slapped her with his right hand, but we noticed he wrote left-handed. Everyone we knew punched and slapped with their dominant hand, not their weaker one. This wasn’t merely a potential crime, but an unresolved mystery.

We, a jury of three men and nine women, found the accused not guilty.

The prosecution was stunned. They had everything going for them– a pretty blonde victim, a dark, dangerous-looking Muslim kid, and a predominantly female panel in a post-9/11 atmosphere — yet they lost. Prosecutors asked the judge to poll the jury. When we stood by our decision, they asked the judge to individually question the jurors.

We knew we didn’t have all the answers, but I was proud of us Floridians that day. We showed that in a pained and angry atmosphere, an American jury could still be fair without regard to origin or religion.

Today, I’m happy to say the local take is striving to be fair as well. Friends and neighbors of the victims don’t believe Islam played a rôle, and that mention of ISIS was either misdirection or mere gilding of the deadly lily. Mateen's father simply says he committed a crime against humanity.

One word echoes not just in Orlando but with honorable people everywhere that goodness remains… unbreakable.

19 June 2016

Unbreakable

by Leigh Lundin

18 June 2016

That's a Mystery to ME

by John Floyd

There are several questions that always seem to come up, at conferences, classes, meetings, signings, and wherever else writers get together with readers or other writers. You know the ones I mean. Should fiction be outlined? Do you edit as you go? Which is more important, plot or character? Where do you get your ideas? Do you assign yourself a page/word quota? Do you write in a certain location, or at a certain time of day?

And one that I hear really often: What, exactly, IS a mystery?

What is it indeed? Does it have to be a whodunit? Must it include a murder? Must it always feature a detective? It's one of those arguments that could be called, well, mysterious.

Criminal activity

To me, the answer is clear. I agree with Otto Penzler, the man who founded Mysterious Press, owns the Mysterious Bookshop in Manhattan, and has for the past nineteen years edited the annual Best American Mystery Stories anthology. Otto says, in every introduction to B.A.M.S., that he considers a mystery to be "any work of fiction in which a crime, or the threat of a crime, is central to the theme or the plot."

To me, the answer is clear. I agree with Otto Penzler, the man who founded Mysterious Press, owns the Mysterious Bookshop in Manhattan, and has for the past nineteen years edited the annual Best American Mystery Stories anthology. Otto says, in every introduction to B.A.M.S., that he considers a mystery to be "any work of fiction in which a crime, or the threat of a crime, is central to the theme or the plot."

NOTE: In looking over the Amazon reviews for The Best American Mystery Stories 2015, I notice that several reviewers said they didn't like it because it included stories that weren't mysteries. My response would be that they didn't read the intro. It doesn't leave much room for doubt.

Why is such a definition important? Does it even matter? I think it does. It's important because writers need to know what they've written in order to know where to submit it. If a magazine (or anthology) editor or a book publisher or agent says he or she is looking for mystery stories/novels, then you/I/we need to know what to send and what not to send. And, again, Otto's definition seems logical. I think mysteries can be whodunits, howdunits, whydunits, etc. (Much has been said at this blog recently about the TV series Columbo, and while I think all of us would classify those episodes as mysteries, none of them were whodunits. All were howcatchems.)

Consider this: If a character spends an entire story or novel trying to murder someone and is stopped just before doing it (The Day of the Jackal, maybe?) does that story or novel fall into the mystery category? Sure it does. A crime--the threat of a crime, in this case--is central to the plot. And I can think of a few mysteries aired on Alfred Hitchcock Presents that didn't even involve a crime. One example is Man From the South, featuring Steve McQueen and adapted from the short story of the same name by Roald Dahl, and another is Breakdown, starring Joseph Cotten as a paralyzed accident victim whose rescuers believe he's dead. Some of you might've seen those, and if you did you'll remember that they were more suspenseful than mysterious.

I'll take Stephen King for 100, Alex

Another thing that always seems to surface in a discussion like this is the fact that some literary authors and publishers look down their noses at the mystery genre and mystery writers. At least two successful crime writers have told me there are certain upscale independent bookstores that aren't terribly receptive to having them come there to sign. The store owners allow it, because--uppity or not--bookstores must make a profit, and successful genre authors usually sell more books than successful literary authors. But there's still a bias. It's been said that Stephen King was for years accused of writing nothing but commercial/popular/genre fiction, until the publication of "The Man in the Black Suit" in The New Yorker and his pseudo-literary novel Bag of Bones. After that, critics began acknowledging that his work is occasionally (in their words) meaningful and profound.

Another thing that always seems to surface in a discussion like this is the fact that some literary authors and publishers look down their noses at the mystery genre and mystery writers. At least two successful crime writers have told me there are certain upscale independent bookstores that aren't terribly receptive to having them come there to sign. The store owners allow it, because--uppity or not--bookstores must make a profit, and successful genre authors usually sell more books than successful literary authors. But there's still a bias. It's been said that Stephen King was for years accused of writing nothing but commercial/popular/genre fiction, until the publication of "The Man in the Black Suit" in The New Yorker and his pseudo-literary novel Bag of Bones. After that, critics began acknowledging that his work is occasionally (in their words) meaningful and profound.

To get back to the subject of this column, though, I also find it interesting that King, who is of course best known for horror fiction, won a well-deserved Edgar Award last year for the novel Mr. Mercedes and another Edgar this year for his short story "Obits." Neither of them fit into some folks' idea of a mystery. The novel was more of a suspense/thriller, and "Obits" was firmly entombed in the spooky/otherwordly/paranormal category. My point is that the Edgar is awarded by Mystery Writers of America, and that in itself means those two works should be considered to be--among other things--mysteries.

Check the label

I remember something Rob Lopresti said to me years ago, on this "what is a mystery?" topic. He said "Definitions tend to be more useful for starting arguments that for ending them." In fact, with all this talk of which cubbyhole to put what in, I'm reminded of a poem I once wrote (and sold, believe it or not), called "A Short Career." Like all my poetry, it tends to be more silly than useful, but I think this one happens to (accidentally) illustrate a point:

I remember something Rob Lopresti said to me years ago, on this "what is a mystery?" topic. He said "Definitions tend to be more useful for starting arguments that for ending them." In fact, with all this talk of which cubbyhole to put what in, I'm reminded of a poem I once wrote (and sold, believe it or not), called "A Short Career." Like all my poetry, it tends to be more silly than useful, but I think this one happens to (accidentally) illustrate a point:

Eddie knew that a detective wears an

Overcoat and hat,

But he lost his pipe and magnifying

Glass, so that was that.

What Eddie didn't understand is that very few things in this life are simple and elementary, my dear Watson. Sometimes the prettiest colors are those that are blended, or at least mixed-and-matched. I think mystery is a broad category, and--IMHO--hybrids are welcome.

It's probably worth mentioning that Elmore Leonard--who was once recognized as a Grand Master by Mystery Writers of America--was always quick to point out that he'd never in his life written a traditional mystery. His stories and novels were about crime and deception, not detection. Even so, the best place to find his work is in the MYSTERY section of the bookstore.

Final Jeopardy question:

What's your take, on this particular argument? Do you think books and stories that lean more toward "suspense" or "thriller" should always be so labeled, or at least identified as a subgenre of "mystery"? Or do you agree that the inclusion of a crime qualifies any such story to be called a mystery?

Investigative minds want to know.

And one that I hear really often: What, exactly, IS a mystery?

What is it indeed? Does it have to be a whodunit? Must it include a murder? Must it always feature a detective? It's one of those arguments that could be called, well, mysterious.

Criminal activity

To me, the answer is clear. I agree with Otto Penzler, the man who founded Mysterious Press, owns the Mysterious Bookshop in Manhattan, and has for the past nineteen years edited the annual Best American Mystery Stories anthology. Otto says, in every introduction to B.A.M.S., that he considers a mystery to be "any work of fiction in which a crime, or the threat of a crime, is central to the theme or the plot."

To me, the answer is clear. I agree with Otto Penzler, the man who founded Mysterious Press, owns the Mysterious Bookshop in Manhattan, and has for the past nineteen years edited the annual Best American Mystery Stories anthology. Otto says, in every introduction to B.A.M.S., that he considers a mystery to be "any work of fiction in which a crime, or the threat of a crime, is central to the theme or the plot."NOTE: In looking over the Amazon reviews for The Best American Mystery Stories 2015, I notice that several reviewers said they didn't like it because it included stories that weren't mysteries. My response would be that they didn't read the intro. It doesn't leave much room for doubt.

Why is such a definition important? Does it even matter? I think it does. It's important because writers need to know what they've written in order to know where to submit it. If a magazine (or anthology) editor or a book publisher or agent says he or she is looking for mystery stories/novels, then you/I/we need to know what to send and what not to send. And, again, Otto's definition seems logical. I think mysteries can be whodunits, howdunits, whydunits, etc. (Much has been said at this blog recently about the TV series Columbo, and while I think all of us would classify those episodes as mysteries, none of them were whodunits. All were howcatchems.)

Consider this: If a character spends an entire story or novel trying to murder someone and is stopped just before doing it (The Day of the Jackal, maybe?) does that story or novel fall into the mystery category? Sure it does. A crime--the threat of a crime, in this case--is central to the plot. And I can think of a few mysteries aired on Alfred Hitchcock Presents that didn't even involve a crime. One example is Man From the South, featuring Steve McQueen and adapted from the short story of the same name by Roald Dahl, and another is Breakdown, starring Joseph Cotten as a paralyzed accident victim whose rescuers believe he's dead. Some of you might've seen those, and if you did you'll remember that they were more suspenseful than mysterious.

I'll take Stephen King for 100, Alex

Another thing that always seems to surface in a discussion like this is the fact that some literary authors and publishers look down their noses at the mystery genre and mystery writers. At least two successful crime writers have told me there are certain upscale independent bookstores that aren't terribly receptive to having them come there to sign. The store owners allow it, because--uppity or not--bookstores must make a profit, and successful genre authors usually sell more books than successful literary authors. But there's still a bias. It's been said that Stephen King was for years accused of writing nothing but commercial/popular/genre fiction, until the publication of "The Man in the Black Suit" in The New Yorker and his pseudo-literary novel Bag of Bones. After that, critics began acknowledging that his work is occasionally (in their words) meaningful and profound.

Another thing that always seems to surface in a discussion like this is the fact that some literary authors and publishers look down their noses at the mystery genre and mystery writers. At least two successful crime writers have told me there are certain upscale independent bookstores that aren't terribly receptive to having them come there to sign. The store owners allow it, because--uppity or not--bookstores must make a profit, and successful genre authors usually sell more books than successful literary authors. But there's still a bias. It's been said that Stephen King was for years accused of writing nothing but commercial/popular/genre fiction, until the publication of "The Man in the Black Suit" in The New Yorker and his pseudo-literary novel Bag of Bones. After that, critics began acknowledging that his work is occasionally (in their words) meaningful and profound.To get back to the subject of this column, though, I also find it interesting that King, who is of course best known for horror fiction, won a well-deserved Edgar Award last year for the novel Mr. Mercedes and another Edgar this year for his short story "Obits." Neither of them fit into some folks' idea of a mystery. The novel was more of a suspense/thriller, and "Obits" was firmly entombed in the spooky/otherwordly/paranormal category. My point is that the Edgar is awarded by Mystery Writers of America, and that in itself means those two works should be considered to be--among other things--mysteries.

Check the label

I remember something Rob Lopresti said to me years ago, on this "what is a mystery?" topic. He said "Definitions tend to be more useful for starting arguments that for ending them." In fact, with all this talk of which cubbyhole to put what in, I'm reminded of a poem I once wrote (and sold, believe it or not), called "A Short Career." Like all my poetry, it tends to be more silly than useful, but I think this one happens to (accidentally) illustrate a point:

I remember something Rob Lopresti said to me years ago, on this "what is a mystery?" topic. He said "Definitions tend to be more useful for starting arguments that for ending them." In fact, with all this talk of which cubbyhole to put what in, I'm reminded of a poem I once wrote (and sold, believe it or not), called "A Short Career." Like all my poetry, it tends to be more silly than useful, but I think this one happens to (accidentally) illustrate a point:Eddie knew that a detective wears an

Overcoat and hat,

But he lost his pipe and magnifying

Glass, so that was that.

What Eddie didn't understand is that very few things in this life are simple and elementary, my dear Watson. Sometimes the prettiest colors are those that are blended, or at least mixed-and-matched. I think mystery is a broad category, and--IMHO--hybrids are welcome.

It's probably worth mentioning that Elmore Leonard--who was once recognized as a Grand Master by Mystery Writers of America--was always quick to point out that he'd never in his life written a traditional mystery. His stories and novels were about crime and deception, not detection. Even so, the best place to find his work is in the MYSTERY section of the bookstore.

Final Jeopardy question:

What's your take, on this particular argument? Do you think books and stories that lean more toward "suspense" or "thriller" should always be so labeled, or at least identified as a subgenre of "mystery"? Or do you agree that the inclusion of a crime qualifies any such story to be called a mystery?

Investigative minds want to know.

17 June 2016

Comicon Results

by Dixon Hill

ComicCon results from two weeks ago:

"Zombie's one -- Human's zero!"

That, at least, is the way our nurse claimed that the X-ray tech reported the results of my wife's foot exam two Saturdays ago. Those of you who read my last post, know that my son attended ComicCon in Phoenix. But, what I didn't tell you is that my wife, Madeleine, went with him on Saturday because I had to work.

The first thing they did, upon entering, was scramble up to the top floor of the Phoenix Convention Center to the Zombie fighting exhibit, in which patrons pay a buck to be issued a cap gun and make their way through a cloth maze populated by folks dressed as zombies, who in-turn growl, lunge, grab at, and sometimes lightly grasp said patrons as they pass. Want to make the zombie quit attacking you, shoot it in the head with your cap gun.

My wife understood the rules -- All but one!

You have to shoot a zombie in the HEAD, because that's the seat of the creature's malfunctioning brain. My wife blazed away at the zombies, who mostly fell down -- except for one female of he species, who kept coming back for more. When she snatched at Madeleine's foot, my wife stepped back and turned in the same instant.

Her reward? The zombie gave up, and the fifth metatarsal (the long bone in the foot behind the pinky toe) on Mad's right foot went POP! A spiral fracture, which the doctor said is sometimes called, "The dancer's break," due to the rotating back step that often proves the catalyst. My wife, whom I first met while we both members of the 101st Airborne Division, then proceeded to accompany my son through the rest of that day's Comicon, a task that necessitates walking for (quite literally -- in the true sense of the word) miles.

She proved a sensation at the hospital that evening, however. Nurses and orderlies kept sneeking in to ask, "Is it true? You broke your foot fighting zombies? How AWESOME!"

"You're a celebrity," I told her.

"We're getting old." She shook her head. "They aren't excited about the zombies. It's the idea that an old lady broke her foot while fighting zombies. That's what they find awesome."

"Oh, that's not true," I replied.

"Yes it is. And we are getting old."

| Our sons, Joe (with beard) and Quentin (red shirt,cowboy hat) appear on the evening news, in a story about Comicon. |

"Your not old! You're not even fifty, honey!"

She rolled her eyes. "You're killing me here. You're killing me."

Maybe I should have said, "...not even forty...."

Both of my feet still work, so duty calls.

I'll see you again in two weeks!

--Dixon

16 June 2016

The Mysterious Sources of Ideas

by Janice Law

by Janice Law

I guess that the most frequent question writers get, along with recommendations for agents or publishers, is “Where do your ideas come from?”

In response, one waggish author is supposed to have replied that he ordered them wholesale.

In response, one waggish author is supposed to have replied that he ordered them wholesale.

Would that were true! A few lucky souls seem to produce an unending stream of good and marketable ideas. Consider the great 19th century great galley slaves of literature like George Sand, Charles Dickens, Anthony Trollope or Honore de Balzac. Nearer to hand, there’s our own Joyce Carol Oates or any of the thriller writers who, with a stable of helpers, adorn the best seller lists month after month. Clearly they rarely have to beg the Muse for ideas, and they write The End only to start afresh at Chapter One.

But I suspect that most writers are beset sooner or later with fears that another story, novel, article, or blog will not be forthcoming. Then it’s the writer’s turn to ask where ideas come from and how they can be persuaded to appear regularly.

After forty years, I still have no definitive answer, but I do know some of the conditions that encourage inspiration. First, ideas in writing or painting, and I would guess the other arts as well, come from work. The genesis of art (or even pulp fiction) is the ultimate chicken and egg conundrum. Amateurs who say, I’d love to write but I don’t have any ideas, have it backwards. Writing produces ideas, which, in turn, produces writing.

After forty years, I still have no definitive answer, but I do know some of the conditions that encourage inspiration. First, ideas in writing or painting, and I would guess the other arts as well, come from work. The genesis of art (or even pulp fiction) is the ultimate chicken and egg conundrum. Amateurs who say, I’d love to write but I don’t have any ideas, have it backwards. Writing produces ideas, which, in turn, produces writing.

Perhaps the writing that primes the pump, so to speak, need not be the final product. I’m always surprised at the massive volumes of famous writers’ correspondence. When did they have time to write those hundreds, sometimes thousands, of letters? And we’re not talking emails, either, but long screeds – and in pen and ink, too. Others wrote not just letters but kept journals or wrote reviews and columns and left memoirs. I suspect such productivity fed the novels, plays and stories, even as it took time from the main work.

Though crucial, writing itself is not enough. Books, the daily papers, and certain true crime TV shows have been useful for me. My newest novel, Homeward Dove, grew from a couple inches of print years ago in the London Telegraph. The Countess came from a couple pages in a children’s book about spies, while The Night Bus owed its inspiration to an episode of Unsolved Mysteries.

But while the public works overtime for the crime writer, material and the practice of writing have to be combined with a certain sort of observational alertness. An example from my own career: at one point, I was doing features of a vaguely business nature for a local paper, things like considering the then new proliferation of office greenery or explaining where stale bread went. I did this for a while and never had a problem with seeing publishable angles. Then the gig stopped. I don’t think I’ve had a single idea for a similar story since.

The reason, I suspect, is that composition requires another ingredient, and that is the enlistment of the subconscious, both in daylight hours to notice things and after working hours, to bring the unexpected together. Maybe clever people who can plot out a whole novel do not need this assistance, but I do, and I often find myself on the verge of sleep giving orders to whatever neurons are in charge: finish the scene at the bridge; resolve the conflict between Fletcher and the Leader, or simply, next five pages, please. Works for me.

After many years of writing, I have clearly semi-trained my subconscious. This is not to say all its ideas are brilliant or that the solution is always waiting for me the next morning. But the mysterious appearance of solutions does emphasize inspiration’s dependence on habit, on observation, and on work. The Muse, it turns out, has to be courted. Writing, writing, writing turns out to be the required offering for this capricious deity.

After many years of writing, I have clearly semi-trained my subconscious. This is not to say all its ideas are brilliant or that the solution is always waiting for me the next morning. But the mysterious appearance of solutions does emphasize inspiration’s dependence on habit, on observation, and on work. The Muse, it turns out, has to be courted. Writing, writing, writing turns out to be the required offering for this capricious deity.

I guess that the most frequent question writers get, along with recommendations for agents or publishers, is “Where do your ideas come from?”

In response, one waggish author is supposed to have replied that he ordered them wholesale.

In response, one waggish author is supposed to have replied that he ordered them wholesale.Would that were true! A few lucky souls seem to produce an unending stream of good and marketable ideas. Consider the great 19th century great galley slaves of literature like George Sand, Charles Dickens, Anthony Trollope or Honore de Balzac. Nearer to hand, there’s our own Joyce Carol Oates or any of the thriller writers who, with a stable of helpers, adorn the best seller lists month after month. Clearly they rarely have to beg the Muse for ideas, and they write The End only to start afresh at Chapter One.

But I suspect that most writers are beset sooner or later with fears that another story, novel, article, or blog will not be forthcoming. Then it’s the writer’s turn to ask where ideas come from and how they can be persuaded to appear regularly.

After forty years, I still have no definitive answer, but I do know some of the conditions that encourage inspiration. First, ideas in writing or painting, and I would guess the other arts as well, come from work. The genesis of art (or even pulp fiction) is the ultimate chicken and egg conundrum. Amateurs who say, I’d love to write but I don’t have any ideas, have it backwards. Writing produces ideas, which, in turn, produces writing.

After forty years, I still have no definitive answer, but I do know some of the conditions that encourage inspiration. First, ideas in writing or painting, and I would guess the other arts as well, come from work. The genesis of art (or even pulp fiction) is the ultimate chicken and egg conundrum. Amateurs who say, I’d love to write but I don’t have any ideas, have it backwards. Writing produces ideas, which, in turn, produces writing.Perhaps the writing that primes the pump, so to speak, need not be the final product. I’m always surprised at the massive volumes of famous writers’ correspondence. When did they have time to write those hundreds, sometimes thousands, of letters? And we’re not talking emails, either, but long screeds – and in pen and ink, too. Others wrote not just letters but kept journals or wrote reviews and columns and left memoirs. I suspect such productivity fed the novels, plays and stories, even as it took time from the main work.

Though crucial, writing itself is not enough. Books, the daily papers, and certain true crime TV shows have been useful for me. My newest novel, Homeward Dove, grew from a couple inches of print years ago in the London Telegraph. The Countess came from a couple pages in a children’s book about spies, while The Night Bus owed its inspiration to an episode of Unsolved Mysteries.

But while the public works overtime for the crime writer, material and the practice of writing have to be combined with a certain sort of observational alertness. An example from my own career: at one point, I was doing features of a vaguely business nature for a local paper, things like considering the then new proliferation of office greenery or explaining where stale bread went. I did this for a while and never had a problem with seeing publishable angles. Then the gig stopped. I don’t think I’ve had a single idea for a similar story since.

The reason, I suspect, is that composition requires another ingredient, and that is the enlistment of the subconscious, both in daylight hours to notice things and after working hours, to bring the unexpected together. Maybe clever people who can plot out a whole novel do not need this assistance, but I do, and I often find myself on the verge of sleep giving orders to whatever neurons are in charge: finish the scene at the bridge; resolve the conflict between Fletcher and the Leader, or simply, next five pages, please. Works for me.

After many years of writing, I have clearly semi-trained my subconscious. This is not to say all its ideas are brilliant or that the solution is always waiting for me the next morning. But the mysterious appearance of solutions does emphasize inspiration’s dependence on habit, on observation, and on work. The Muse, it turns out, has to be courted. Writing, writing, writing turns out to be the required offering for this capricious deity.

After many years of writing, I have clearly semi-trained my subconscious. This is not to say all its ideas are brilliant or that the solution is always waiting for me the next morning. But the mysterious appearance of solutions does emphasize inspiration’s dependence on habit, on observation, and on work. The Muse, it turns out, has to be courted. Writing, writing, writing turns out to be the required offering for this capricious deity.15 June 2016

The Scientist and the Man in Black

Call this the third in my extremely occasional series of reviews of non-fiction books. As before I am including two at no extra cost.

Forensics by Val McDermid, is a terrific guide to the science of crime-solving. McDermid was a reporter before she became a best-selling crime writer and it shows. She gives you just enough of the technology, while focusing on the people, and often on the history.

For example, the chapter on entomology begins with the earliest recorded case of insects being used in the investigation of a crime. In China in 1247 a man was found murdered with, it was determined, a sickle. The coroner ordered all 70 men in the area to stand together with their sickles. Flies immediately detected what the eyes couldn't, identifying the guilty man by landing on his weapon to feast on traces of blood.

There are chapters on fire scene investigation, pathology, toxicology, digital forensics, and much more. McDermid tells of heroic scientists, and others who botched their work, usually out of over-confidence. Sometimes their mistakes ruin, or even end, the lives of suspects.

One horror story is that of Colin Stagg, an Englishman who seemed a perfect match for a forensic profiler's description of the man who killed a woman in a London park in 1992. The cops tried hard to prove he was the man, even introducing him to a policewoman who claimed to be attracted to him and into rough sex. Astonishingly, this guy who had apparently never had a successful relationship with a woman, offered to give her what she said she wanted. Clearly proof of guilt!

The judge politely called the prosecution's theory of the case "highly disingenuous" and dismissed it. The policewoman took early retirement for PTSD, and Stagg was awarded a ton of money because his name was so ruined he couldn't find work. In 2008 another man was convicted of the murder, based on DNA evidence.

The last chapter is about giving courtroom evidence, which most of the scientists appear to hate. I suppose if an attorney was going to try to make me seem incompetent and dishonest I wouldn't like it either.

But I do like Forensics, and highly recommend it.

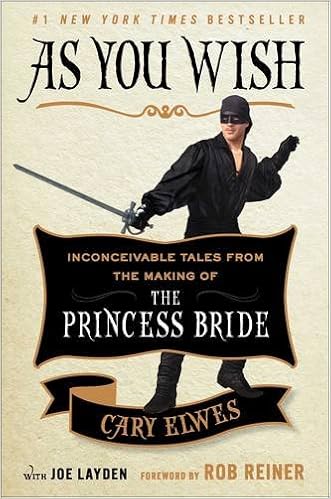

Unlike all the other books I have reviewed in this series, As You Wish by Cary Elwes has nothing to do with crime. But it certainly has something to do with writing, specifically one of the best-written movies of all time. If you aren't a fan of The Princess Bride you may stop reading right now (and never darken my towels again, as Groucho Marx said).

Unlike all the other books I have reviewed in this series, As You Wish by Cary Elwes has nothing to do with crime. But it certainly has something to do with writing, specifically one of the best-written movies of all time. If you aren't a fan of The Princess Bride you may stop reading right now (and never darken my towels again, as Groucho Marx said).

Cary Elwes, of course, played Westley in that movie and, to celebrate its 25th anniversary he has published his memoir of the filming of the show. If you love this flick you will relish his stories. For example:

*William Goldman, who wrote the novel and the script (which for many years was considered by Hollywood one of the best unfilmable scripts around) was terrified that director Rob Reiner would butcher his darling work. On the first day of filming the sound man picked up a strange noise. It was Goldman, at the other end of the set, praying.

*Remember the sword fight between Inigo Montoya and the Man in Black? Except for the swing on the horizontal bar, there were no stunt doubles (well, I have my doubts about Patinkin's flying somersault). You are seeing four months of daily training with Olympic fencers and a solid week of filming.

*Wallace Shawn, who played Vizzini, was terrified that Reiner was going to replace him. Making things worse, the vagaries of film scheduling meant that his first scene was his most complicated: the Battle of Wits.

*Wallace Shawn, who played Vizzini, was terrified that Reiner was going to replace him. Making things worse, the vagaries of film scheduling meant that his first scene was his most complicated: the Battle of Wits.

* Remember the scene where the six-fingered man strikes Westley with the butt of his sword and he falls down unconscious? That wasn't acting. He woke up in the hospital.

*When Andre the Giant (who played Fezzik, of course) was a child in rural France he outgrew the school bus, so every day he was driven to school by the only man in town who owned a convertible: the playwright Samuel Beckett.

So, if you love this movie, read this book. To do otherwise would be... (say it with me) inconceivable.

Forensics by Val McDermid, is a terrific guide to the science of crime-solving. McDermid was a reporter before she became a best-selling crime writer and it shows. She gives you just enough of the technology, while focusing on the people, and often on the history.

For example, the chapter on entomology begins with the earliest recorded case of insects being used in the investigation of a crime. In China in 1247 a man was found murdered with, it was determined, a sickle. The coroner ordered all 70 men in the area to stand together with their sickles. Flies immediately detected what the eyes couldn't, identifying the guilty man by landing on his weapon to feast on traces of blood.

There are chapters on fire scene investigation, pathology, toxicology, digital forensics, and much more. McDermid tells of heroic scientists, and others who botched their work, usually out of over-confidence. Sometimes their mistakes ruin, or even end, the lives of suspects.

One horror story is that of Colin Stagg, an Englishman who seemed a perfect match for a forensic profiler's description of the man who killed a woman in a London park in 1992. The cops tried hard to prove he was the man, even introducing him to a policewoman who claimed to be attracted to him and into rough sex. Astonishingly, this guy who had apparently never had a successful relationship with a woman, offered to give her what she said she wanted. Clearly proof of guilt!

The judge politely called the prosecution's theory of the case "highly disingenuous" and dismissed it. The policewoman took early retirement for PTSD, and Stagg was awarded a ton of money because his name was so ruined he couldn't find work. In 2008 another man was convicted of the murder, based on DNA evidence.

The last chapter is about giving courtroom evidence, which most of the scientists appear to hate. I suppose if an attorney was going to try to make me seem incompetent and dishonest I wouldn't like it either.

But I do like Forensics, and highly recommend it.

Unlike all the other books I have reviewed in this series, As You Wish by Cary Elwes has nothing to do with crime. But it certainly has something to do with writing, specifically one of the best-written movies of all time. If you aren't a fan of The Princess Bride you may stop reading right now (and never darken my towels again, as Groucho Marx said).

Unlike all the other books I have reviewed in this series, As You Wish by Cary Elwes has nothing to do with crime. But it certainly has something to do with writing, specifically one of the best-written movies of all time. If you aren't a fan of The Princess Bride you may stop reading right now (and never darken my towels again, as Groucho Marx said). Cary Elwes, of course, played Westley in that movie and, to celebrate its 25th anniversary he has published his memoir of the filming of the show. If you love this flick you will relish his stories. For example:

*William Goldman, who wrote the novel and the script (which for many years was considered by Hollywood one of the best unfilmable scripts around) was terrified that director Rob Reiner would butcher his darling work. On the first day of filming the sound man picked up a strange noise. It was Goldman, at the other end of the set, praying.

*Remember the sword fight between Inigo Montoya and the Man in Black? Except for the swing on the horizontal bar, there were no stunt doubles (well, I have my doubts about Patinkin's flying somersault). You are seeing four months of daily training with Olympic fencers and a solid week of filming.

*Wallace Shawn, who played Vizzini, was terrified that Reiner was going to replace him. Making things worse, the vagaries of film scheduling meant that his first scene was his most complicated: the Battle of Wits.

*Wallace Shawn, who played Vizzini, was terrified that Reiner was going to replace him. Making things worse, the vagaries of film scheduling meant that his first scene was his most complicated: the Battle of Wits.* Remember the scene where the six-fingered man strikes Westley with the butt of his sword and he falls down unconscious? That wasn't acting. He woke up in the hospital.

*When Andre the Giant (who played Fezzik, of course) was a child in rural France he outgrew the school bus, so every day he was driven to school by the only man in town who owned a convertible: the playwright Samuel Beckett.

So, if you love this movie, read this book. To do otherwise would be... (say it with me) inconceivable.

Labels:

Cary Elwes,

Colin Stagg,

forensics,

Val McDermid,

William Goldman

14 June 2016

Warning! There's a Storm Coming!

by Barb Goffman

We've all heard the famous advice--never start your story with the weather. Horrors! The weather! Run for your lives!

Actually, if a story began with a storm brewing so horrifically that people were actually running for their lives, that would be a good start. It would have action. Drama. It would draw the reader in.

But then there's the other way to start with weather, and it's the reason for the weather taboo: the dreaded story that begins with tons and tons of description, including about the weather, but no action. Imagine: Jane Doe awoke. She stretched her shoulders, looked out the window, and relished the bright rays of sunshine streaming down from the cloudless blue sky. It would be a lovely day, Jane knew. The high should be about seventy-five degrees, breezy. No chance of showers. Maybe she would barbecue tonight. It shouldn't be humid out there. It should just be delightful.

By this point, your eyes are probably glazing over. Or you want to strangle Jane for being so boring. When you use the weather this way, setting your scene yet having nothing happening, you are basically asking your reader to find something else to read. Anything else. Cereal box, anyone?

Yet imagine another opening to Jane's day: Thunder clapped, rattling the windows and scaring Jane Doe awake. Holy hell. Thunder in January? She trudged to the window. It was snowing like crazy out there. They hadn't predicted snow, but there had to be more than two feet on the ground. Jane's stomach sunk. She was alone and really low on food. Meals for Wheels would never be able to make it in this weather. Not for days, probably. Maybe a week. Or

more. She should have known something like this might happen again after the blizzard of 2010. She should have prepared. What would she do when the food ran out? What? Just then, her bird started chirping. Arthur. Sweet, friendly, beautiful Arthur. She loved him, just as she had loved Squeaky back in 2010. He had tasted unexpectedly good.

Now you may be grossed out, but you certainly shouldn't be bored. And that's the point: if you use the weather in order to propel the story forward, then it's a good use. With this idea in mind, two years ago, Donna Andrews, Marcia Talley, and I put out a call for stories for Chesapeake Crimes: Storm Warning. We told the members of the Chesapeake Chapter of Sisters in Crime to come up with crime short stories that put the weather front and center. And, boy, did they come through.

Stories were chosen by a team of seasoned authors (former SleuthSayer David Dean, current SleuthSayer B.K. Stevens, and Sujata Massey). The choices were made blindly, meaning the story pickers didn't know who had written each submission. Donna, Marcia, and I then began our editing process (we take a long time with the stories--they all go through multiple drafts).

Finally, the book came out in the last week of April. It has fifteen stories featuring crime mixed in with rain storms, blizzards, hurricanes, sleet, and even a shamal. You want a murder during a white-out at a ski resort. We have that. How about a locked-room murder mystery at a zoo's snake house, where people are stuck inside while a storm rages outside? We've got that too. We have stories of revenge and stories of guilt. Stories featuring characters on the fringes of society and stories featuring well-off expats. And in all the stories, the weather sets the mood and propels the action in ways you won't expect. That's the way to use the weather, as a vehicle to move the plot forward and set the mood.

I use the weather both ways in my story in the book, "Stepmonster," in which a heartbroken, enraged daughter seeks revenge long after her father's death while a storm rages on. The pouring rain sets a dark atmosphere, as the object of revenge cowers in fear, and the thunder offers a nice cover for certain ... sounds.

I'd love to hear about your favorite books or stories that put the weather to good use. Please share in the comments. And Storm Warning authors, please drop in to let the readers know about your stories.

And, finally, I'd like to give a shout-out to fellow SleuthSayers who were nominated for the Macavity Award on Saturday: Art Taylor for best first mystery for On the Road with Del and Louise, and B.K. Stevens for best short story for "A Joy Forever" from the March 2015 issue of Alfred Hitchcock's Mystery Magazine. (I'm also up for best short story--yay!--for my story "A Year Without Santa Claus?" from the January/February 2015 issue of Alfred Hitchcock's Mystery Magazine.) You can read B.K.'s story here. And you can read my story by clicking here. I'm trying to get links for all the stories together for Janet Rudolph, the woman behind the Macavity Award. I'll let you all know if and when that happens.

And, finally, I'd like to give a shout-out to fellow SleuthSayers who were nominated for the Macavity Award on Saturday: Art Taylor for best first mystery for On the Road with Del and Louise, and B.K. Stevens for best short story for "A Joy Forever" from the March 2015 issue of Alfred Hitchcock's Mystery Magazine. (I'm also up for best short story--yay!--for my story "A Year Without Santa Claus?" from the January/February 2015 issue of Alfred Hitchcock's Mystery Magazine.) You can read B.K.'s story here. And you can read my story by clicking here. I'm trying to get links for all the stories together for Janet Rudolph, the woman behind the Macavity Award. I'll let you all know if and when that happens.

Actually, if a story began with a storm brewing so horrifically that people were actually running for their lives, that would be a good start. It would have action. Drama. It would draw the reader in.

But then there's the other way to start with weather, and it's the reason for the weather taboo: the dreaded story that begins with tons and tons of description, including about the weather, but no action. Imagine: Jane Doe awoke. She stretched her shoulders, looked out the window, and relished the bright rays of sunshine streaming down from the cloudless blue sky. It would be a lovely day, Jane knew. The high should be about seventy-five degrees, breezy. No chance of showers. Maybe she would barbecue tonight. It shouldn't be humid out there. It should just be delightful.

By this point, your eyes are probably glazing over. Or you want to strangle Jane for being so boring. When you use the weather this way, setting your scene yet having nothing happening, you are basically asking your reader to find something else to read. Anything else. Cereal box, anyone?

Yet imagine another opening to Jane's day: Thunder clapped, rattling the windows and scaring Jane Doe awake. Holy hell. Thunder in January? She trudged to the window. It was snowing like crazy out there. They hadn't predicted snow, but there had to be more than two feet on the ground. Jane's stomach sunk. She was alone and really low on food. Meals for Wheels would never be able to make it in this weather. Not for days, probably. Maybe a week. Or

more. She should have known something like this might happen again after the blizzard of 2010. She should have prepared. What would she do when the food ran out? What? Just then, her bird started chirping. Arthur. Sweet, friendly, beautiful Arthur. She loved him, just as she had loved Squeaky back in 2010. He had tasted unexpectedly good.

Now you may be grossed out, but you certainly shouldn't be bored. And that's the point: if you use the weather in order to propel the story forward, then it's a good use. With this idea in mind, two years ago, Donna Andrews, Marcia Talley, and I put out a call for stories for Chesapeake Crimes: Storm Warning. We told the members of the Chesapeake Chapter of Sisters in Crime to come up with crime short stories that put the weather front and center. And, boy, did they come through.

Stories were chosen by a team of seasoned authors (former SleuthSayer David Dean, current SleuthSayer B.K. Stevens, and Sujata Massey). The choices were made blindly, meaning the story pickers didn't know who had written each submission. Donna, Marcia, and I then began our editing process (we take a long time with the stories--they all go through multiple drafts).

Finally, the book came out in the last week of April. It has fifteen stories featuring crime mixed in with rain storms, blizzards, hurricanes, sleet, and even a shamal. You want a murder during a white-out at a ski resort. We have that. How about a locked-room murder mystery at a zoo's snake house, where people are stuck inside while a storm rages outside? We've got that too. We have stories of revenge and stories of guilt. Stories featuring characters on the fringes of society and stories featuring well-off expats. And in all the stories, the weather sets the mood and propels the action in ways you won't expect. That's the way to use the weather, as a vehicle to move the plot forward and set the mood.

I use the weather both ways in my story in the book, "Stepmonster," in which a heartbroken, enraged daughter seeks revenge long after her father's death while a storm rages on. The pouring rain sets a dark atmosphere, as the object of revenge cowers in fear, and the thunder offers a nice cover for certain ... sounds.

I'd love to hear about your favorite books or stories that put the weather to good use. Please share in the comments. And Storm Warning authors, please drop in to let the readers know about your stories.

And, finally, I'd like to give a shout-out to fellow SleuthSayers who were nominated for the Macavity Award on Saturday: Art Taylor for best first mystery for On the Road with Del and Louise, and B.K. Stevens for best short story for "A Joy Forever" from the March 2015 issue of Alfred Hitchcock's Mystery Magazine. (I'm also up for best short story--yay!--for my story "A Year Without Santa Claus?" from the January/February 2015 issue of Alfred Hitchcock's Mystery Magazine.) You can read B.K.'s story here. And you can read my story by clicking here. I'm trying to get links for all the stories together for Janet Rudolph, the woman behind the Macavity Award. I'll let you all know if and when that happens.

And, finally, I'd like to give a shout-out to fellow SleuthSayers who were nominated for the Macavity Award on Saturday: Art Taylor for best first mystery for On the Road with Del and Louise, and B.K. Stevens for best short story for "A Joy Forever" from the March 2015 issue of Alfred Hitchcock's Mystery Magazine. (I'm also up for best short story--yay!--for my story "A Year Without Santa Claus?" from the January/February 2015 issue of Alfred Hitchcock's Mystery Magazine.) You can read B.K.'s story here. And you can read my story by clicking here. I'm trying to get links for all the stories together for Janet Rudolph, the woman behind the Macavity Award. I'll let you all know if and when that happens.

Labels:

Art Taylor,

B.K. Stevens,

Barb Goffman,

David Dean,

Donna Andrews,

Marcia Talley,

Sujata Massey,

weather

13 June 2016

Pardon Me Boys

by Jan Grape

Around thirty years ago there were a little group of women mystery writers, led by Best Selling author, Sara Paretsky who formed a group known as Sisters-in-Crime. Women were being portrayed in violent and sadistic ways in a number of men's books. Women were getting the short end of the stick on money, reviews, accolades, awards and the goal was to try to change that. It went over fairly well. I remember one woman writer I knew from Houston who said, Mystery writers both male and female get shafted as far as reviews and money goes. In a way she was right. But reviewers mainly by-passed mystery novels written by women. And not just because there were the traditional or cozy, not because there were Romantic Suspense. Women mystery writers were just ignored for the most part. it was as if no one thought a woman could write a mystery/suspense/thriller as good as a man. Or that women's mystery novels were as important as a man's.

Taking an approach that monitored book reviews. Most newspapers were quick to push reviews that were more fair to women. You sort of got the idea, that it had never occurred to them. Maybe that's how many things in our patriarcial society got so heavily slanted to the male of the species. Yeah, right. We just never thought women might have a need to borrow money to buy a house or start a business or buy a car or just needed a personal loan. The world began to change during World War II.

Women went to work in jobs that traditionally were given to men. But the men were overseas fighting. As soon as the war was over and the men came home, women were laid off. Many women were not happy about it.

Women had been enjoying their new-found freedom of making enough money to support themselves and their children. Many of these women were now widowed. Or their husbands came home with injuries both physical and mental. Divorces happened. Women needed to go back to work. However they discovered a large disparity in wages. No matter how hard they tried to make things more equal in pay, nothing much was happening. Guess what? That's still how it is. Women still are fighting for equal pay for equal work. It was hugely noticeable in writers. Even though Sisters-in-Crime has made progress, it still is a man's world in publishing. Mainly because women do not have the power positions in publishing houses.

Just to mention one other tidbit. Many male mystery writers have joined Sisters-in-Crime because unless you last name is King, or Connelley or Child (not to take anything away from those guys) you're not being offered as much money as you deserve. Our Brothers-in-Crime found we were not about replacing men mystery authors and we had some good marketing ideas. Besides Sisters have done pretty well. I don't know the membership numbers but it's in the thousands. There are local chapters all over the US and there are even many International Chapters. It's been good, but we're not finished by a long hot. This is our thirtieth year Anniversary.

Two final notes before I close. Just recently we've all seen how even some lawyers and judges feel about women and rape. As a woman, I'm sickened by the non-sentence the Stanford Swimmer, Brock Turner received by the Stanford Alum Judge for sexual assault and rape. I worry about my daughter,, granddaughters, nieces, great nieces and great grandnieces. My cousins, any female of any age in my family. Rape isn't about the twenty minutes of action that young man got. Rape isn't about sex. It's about POWER. Male dominance over female. We must fight against the rape culture of this country.

After what happened in that Orlando club last night, we must continue fighting against hate in whatever shape or form it takes. We must ban these assault weapons. I don't want to take away anyone's guns but those high magazine weapons are only made for wars and for the military to carry. Not the person trying to protect his home and family or the person who wants to hunt. The Congress of these United States need to get untangled from the Gun Manufacturers who pour money into the politicians pockets and do what is right for us.

Pardon me boys. I love you, but WHOO-HOO. It's about danged time we have a strong female candidate for President.

Labels:

guns,

Jan Grape,

rape,

SinC,

Sisters-In-Crime

Location:

Cottonwood Shores, TX 78657, USA

12 June 2016

Muhammad Ali and (not) Me

by Leigh Lundin

by Leigh Lundin

When I was a kid, Cassius Clay defined hero to my friend Rawhide and me. Our little town may have been rural and 99.99% white, but we admired his exuberance, perseverance, and his modesty. You know what I’m talking about: “I’m the greatest, I’m the best.” And he really was.

In the days before multi-thousand-dollar self-improvement seminars, we recognized self-talk. If he could envision it, he could make it so, and so could we. Those lessons became diluted in adulthood, but they still hold true: imagine and make it happen.

Sting Like a Butterfly

Today’s article isn’t about me and it’s barely about Muhammad Ali. It’s really about a friend I’ll call Carla, and yes, she’s blonde, very, very blonde.

Don’t be misled, she’s smart, too, and one of the most charismatic people I’ve ever known. Among other talents, she gave seminars and for years she worked for Disney. Another characteristic was she knew virtually nothing about sports, music and movie stars. Oddly enough, those two traits, charm and lack of knowledge about the rich and famous actually qualified her for a plum job… working with celebrities.

So, by day, she ran– in fact reinvented– Disney’s Research & Documentation Department (named by yours truly in a consulting moment), the how-things-work people. But when Disney hosted ‘special visitors’† or what they call ‘celebrity events’, she’d find herself plucked off the job and assigned to a star of stage, screen, or sports, initially as a chauffeur and later as an attendant.

Disney’s maintains a ‘secure floor’ for VIPs in the Contemporary Hotel. Its attendants are selected because they, like Carla, neither fawn nor fuss. Celebrities are sort of like pets–they have to be fed and watered, played with and exercised without destroying the furniture. It’s a no-nonsense job, but done right, it earns respect. Michael Jackson used to ask for one particular manager simply because that man didn’t know who MJ was.

A Certain State of Being

Two or three times a year, Carla would pack a bag and disappear a week for a ‘celebrity event’. After her first event, we attended a small party with friends who asked who she’d been assigned to. Carla thought back and said, “It was a football guy… Joe… Joe… Oh, yes! Joe Wyoming!”

The only sound was incredulous jaws dropping. Finally one guy said, “You mean Joe Montana? Only the greatest quarterback ever?”

Did I mention Carla’s a natural blonde? She’s very smart and well educated, but she has more than her share of patented blonde ditziness, which she freely admits.

So she served as a driver or guide for the likes of Gladys Knight (“Loved her brother and Cousin Willie”), Dolly Parton (“She’s tiny except where she’s not”), and my favorite, John Lee Hooker.

Although she had to be schooled about George Lucas and Steven Spielberg, she knew who John Ritter was and found herself disappointed. (“He was mean to his wife.”) Here the adage about how one treats lesser mortals comes to the fore. Carla found Katharine Hepburn kind and considerate, but not Lauren Bacall. (“Maybe she was having a bad week.”)

A Real Disney Princess

Carla’s office was above the jewelry store and bakery on Main Street. The upper storeys of buildings are constructed with false fronts: a façade and outer wall, then a narrow passage, and an inner wall that encloses modern offices.

One day the Magic Kingdom grew extremely quiet, not a visitor in sight. Carla dropped downstairs almost into the arms of a special visitor she did recognize: a mother, her two boys, and a friend. Princess Diana and her companion were browsing the shopping counters in an empty park– Disney had closed the entire Magic Kingdom for four visitors.

An Idol Moment

Carla’s regular duties required her to travel around property, Disney’s term for the entire Walt Disney World complex (roughly 30 000 acres, 12 000 hectares), to carefully document how to operate rides, resorts, and hotels. Disney uses a fleet of anonymous white vans and she phoned for one to pick her up at the Contemporary. Dispatch promised to bring a van around within a minute or two.

Carla took a moment to powder her nose. When she stepped outside, she found a Disney van idling, its door open and waiting. She climbed into the van and sat… and found herself staring at a pair of cowboy boots. When she looked up, she found a guy with spiky blond hair staring at her.

“Who are you?” he said.

“Who are you?” she asked in return.

He said, “You may know me as Billy Idol.”

“Sorry I don’t, but I’m Carla.”

As I mentioned, she’s extremely charismatic and within moments he’d opened to her, saying he was waiting for his children so they could visit Space Mountain in the Magic Kingdom. (Disney spirits celebrities into back entrances so they don’t have to wait in queues with hoi polloi.) They chatted like old friends until a second van pulled up, Bill Broad’s family came out, and security figured out there’d been a mix-up.

Knockout

So we come to Muhammad Ali and by now, you know what to expect. Disney was opening their Sports Complex and invited a number of stars for the– repeat after me– celebrity event. Afterwards, Carla endured our interrogation.

“Who’d you get?”

“They told me he’s a boxer plus a sportscaster’s family, Howard something. The boxer trembled a lot. He was a big black guy.”

“You’e kidding. Do you mean Howard Cosell? And Muhammad Ali? Only the greatest ever?”

Even to a white kid from a rural school.

† Items in quotation mark indicate Disney terminology.

When I was a kid, Cassius Clay defined hero to my friend Rawhide and me. Our little town may have been rural and 99.99% white, but we admired his exuberance, perseverance, and his modesty. You know what I’m talking about: “I’m the greatest, I’m the best.” And he really was.

In the days before multi-thousand-dollar self-improvement seminars, we recognized self-talk. If he could envision it, he could make it so, and so could we. Those lessons became diluted in adulthood, but they still hold true: imagine and make it happen.

Sting Like a Butterfly

Today’s article isn’t about me and it’s barely about Muhammad Ali. It’s really about a friend I’ll call Carla, and yes, she’s blonde, very, very blonde.

Don’t be misled, she’s smart, too, and one of the most charismatic people I’ve ever known. Among other talents, she gave seminars and for years she worked for Disney. Another characteristic was she knew virtually nothing about sports, music and movie stars. Oddly enough, those two traits, charm and lack of knowledge about the rich and famous actually qualified her for a plum job… working with celebrities.

So, by day, she ran– in fact reinvented– Disney’s Research & Documentation Department (named by yours truly in a consulting moment), the how-things-work people. But when Disney hosted ‘special visitors’† or what they call ‘celebrity events’, she’d find herself plucked off the job and assigned to a star of stage, screen, or sports, initially as a chauffeur and later as an attendant.

Disney’s maintains a ‘secure floor’ for VIPs in the Contemporary Hotel. Its attendants are selected because they, like Carla, neither fawn nor fuss. Celebrities are sort of like pets–they have to be fed and watered, played with and exercised without destroying the furniture. It’s a no-nonsense job, but done right, it earns respect. Michael Jackson used to ask for one particular manager simply because that man didn’t know who MJ was.

A Certain State of Being

Two or three times a year, Carla would pack a bag and disappear a week for a ‘celebrity event’. After her first event, we attended a small party with friends who asked who she’d been assigned to. Carla thought back and said, “It was a football guy… Joe… Joe… Oh, yes! Joe Wyoming!”

The only sound was incredulous jaws dropping. Finally one guy said, “You mean Joe Montana? Only the greatest quarterback ever?”

Did I mention Carla’s a natural blonde? She’s very smart and well educated, but she has more than her share of patented blonde ditziness, which she freely admits.

So she served as a driver or guide for the likes of Gladys Knight (“Loved her brother and Cousin Willie”), Dolly Parton (“She’s tiny except where she’s not”), and my favorite, John Lee Hooker.

Although she had to be schooled about George Lucas and Steven Spielberg, she knew who John Ritter was and found herself disappointed. (“He was mean to his wife.”) Here the adage about how one treats lesser mortals comes to the fore. Carla found Katharine Hepburn kind and considerate, but not Lauren Bacall. (“Maybe she was having a bad week.”)

A Real Disney Princess

Carla’s office was above the jewelry store and bakery on Main Street. The upper storeys of buildings are constructed with false fronts: a façade and outer wall, then a narrow passage, and an inner wall that encloses modern offices.

One day the Magic Kingdom grew extremely quiet, not a visitor in sight. Carla dropped downstairs almost into the arms of a special visitor she did recognize: a mother, her two boys, and a friend. Princess Diana and her companion were browsing the shopping counters in an empty park– Disney had closed the entire Magic Kingdom for four visitors.

An Idol Moment

Carla’s regular duties required her to travel around property, Disney’s term for the entire Walt Disney World complex (roughly 30 000 acres, 12 000 hectares), to carefully document how to operate rides, resorts, and hotels. Disney uses a fleet of anonymous white vans and she phoned for one to pick her up at the Contemporary. Dispatch promised to bring a van around within a minute or two.

Carla took a moment to powder her nose. When she stepped outside, she found a Disney van idling, its door open and waiting. She climbed into the van and sat… and found herself staring at a pair of cowboy boots. When she looked up, she found a guy with spiky blond hair staring at her.

“Who are you?” he said.

“Who are you?” she asked in return.

He said, “You may know me as Billy Idol.”

“Sorry I don’t, but I’m Carla.”

As I mentioned, she’s extremely charismatic and within moments he’d opened to her, saying he was waiting for his children so they could visit Space Mountain in the Magic Kingdom. (Disney spirits celebrities into back entrances so they don’t have to wait in queues with hoi polloi.) They chatted like old friends until a second van pulled up, Bill Broad’s family came out, and security figured out there’d been a mix-up.

Knockout

So we come to Muhammad Ali and by now, you know what to expect. Disney was opening their Sports Complex and invited a number of stars for the– repeat after me– celebrity event. Afterwards, Carla endured our interrogation.

“Who’d you get?”

“They told me he’s a boxer plus a sportscaster’s family, Howard something. The boxer trembled a lot. He was a big black guy.”

“You’e kidding. Do you mean Howard Cosell? And Muhammad Ali? Only the greatest ever?”

Even to a white kid from a rural school.

† Items in quotation mark indicate Disney terminology.

Labels:

Disney,

Leigh Lundin,

Muhammad Ali

Location:

Orlando, FL, USA

11 June 2016

One More Thing: Is Columbo America's Sherlock?

by Unknown

by B.K. Stevens

If we were asked to name the quintessential fictional detective, most of us would probably reply, "Sherlock Holmes." Poe's Dupin came before him, and some fictional detectives who came after him may have greater psychological depth. Even so, Holmes' dazzling deductions and indelibly distinctive personality have given him enduring worldwide appeal. He's the icon who set the standard for the Golden Age, the epitome of the cerebral detective. And, as I'm about to argue, he's very, very English.

Does America have its own Sherlock? We definitely have iconic fictional detectives. The first names to come to mind might be Sam Spade or Philip Marlowe, Kinsey Millhone or V.I. Warshawski--tough-talking, life-hardened private investigators who walk the mean streets with both guns and cynical quips at the ready. They're smart, no doubt about it. But their appeal may be based on their attitudes, as much as on their intellects. And their success at solving crimes may depend on their ability to intimidate witnesses and outfight bad guys as much as on their deductive powers. America does have some memorable cerebral detectives--Nero Wolfe, for example, and Ellery Queen. Much as their fans might disagree, though, I'd hesitate to call them distinctively American. In some ways, they're almost too much like Sherlock Holmes--arrogant manners, aristocratic tastes. For me, at least, an American Sherlock ought to embody more democratic traits and attitudes.

Let me propose another candidate. Like Holmes, Lieutenant Columbo relies on his wits to solve cases, not on a gun or his fists. (In fact, while Holmes often carries a gun and sometimes throws a punch, I can't think of a single time when Columbo does either.) Both detectives are incredibly observant, and both excel at sizing up suspects. But there are significant differences, too, and I'd say these differences stem from the fact that Holmes is English and Columbo American.

Let's start with names. A name can't get much more thoroughly English than Sherlock Holmes--unless it's Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Even most of the actors who have played Holmes have had distinctively English names, from Basil Rathbone to Benedict Cumberbatch. (And all right, once in a while a Robert Downey, Jr., will sneak in, or even--good grief!--an Igor Petrenko, in a Russian television series. The general point still holds.)

America's Sherlock, by contrast, has an Italian last name. Was it inspired by the explorer credited with discovering the new world? When asked in 1986, one of the writers who created the character said he couldn't remember how they came up with the name--maybe they were thinking of Columbus, or maybe they were thinking of a restaurant called Palumbo's. Those writers, by the way, were Richard Levinson (Jewish) and William Link (mixed German Hugenot and Jewish descent). The actor who portrayed Columbo was Peter Falk (also Jewish, from families that immigrated from Eastern Europe). So Columbo emerged from a hodgepodge of nationalities and ethnicities, from the descendants of a bunch of immigrants. What could be more American?

The fact that so many people contributed to the creation of Columbo also seems appropriately American. Sherlock Holmes was the brainchild of one writer and made his debut, of course, in print, in the pages of a series of short stories and novels. Columbo emerged from what might be considered the more democratic medium of television. Whatever its shortcomings, television depends upon a group of people working together--writers, actors, directors, producers, musicians, technicians, and so on and so on--and it aims for a wide audience. At its best, television also offers opportunities to talented newcomers--such as a twenty-one-year-old kid named Steven Spielberg, who got one of his first big breaks when he directed "Murder by the Book," which many people consider one of the stand-out episodes of Columbo's first season, perhaps of the series as a whole. Whether you love television or hate it, it seems hard to deny that it embodies central democratic ideals--many people from diverse backgrounds working together toward a common goal, encouraging those just starting out to fulfill their dreams by going as far as their abilities will take them.

What about Columbo himself? He's definitely not an aristocrat. The way he talks, the way he carries himself, the car he drives, the chili he eats--everything tells us he's from a middle-class or working-class background. His appearance confirms it. Like Sherlock Holmes, he has a distinctive style of dress. But Sherlock's clothes set him apart--the deerstalker hat, the caped coat. Columbo wears a rumpled suit and a shabby raincoat (almost always the same ones, from Falk's own closet). If his clothes set him apart, it's because he looks less imposing than other people, certainly far less imposing than the high-class types involved in the cases he investigates. In an interview with David Fantle and Tom Johnson, Peter Falk commented on the contrast: "Columbo is an ass-backwards Sherlock Holmes. Holmes had a long neck, Columbo has no neck; Holmes smoked a pipe, Columbo chews up six cigars a day."

In an interview with Mark Dawidziak, Falk made another comment about the contrast between Holmes and Columbo, this one focusing on the way others perceive the two detectives. He's talking about the second episode in the series, which centers on a faked kidnapping: "I'm not a mystery fan, but as a kid I read Sherlock Holmes. I remember being very impressed by Sherlock Holmes. He'd show up, and everybody would turn to him for the answer. I thought it was important in the opening of Ransom for a Dead Man that no one turn to me for anything. I was just a local. All these FBI agents had their job to do. I couldn't know anything except maybe he name of a certain street. I wanted to be ignored. . . . . Nobody wanted to know this guy's opinion, There's a lack of pretension. You expect something quite different from a great detective."

We definitely get something quite different from most great fictional detectives, definitely including Holmes. I don't know if it's accurate to call Holmes pretentious: He is, in fact, superior to everyone else, so there's no pretension involved. But he certainly doesn't try to hide his superiority. Apparently, in Conan Doyle's stories and novels, Holmes never actually says, "Elementary, my dear Watson." He does, however, sometimes say "elementary"--or something along the same lines, such as "it is simplicity itself"--to make it clear he can easily figure out something that baffles others. Some might call his manner arrogant; others might say he treats most of the people he encounters with disdain; still others might protest that he's simply being straightforward. But I don't think words such as "humble" or "self-effacing" come readily to mind when we think of Sherlock Holmes.

Columbo, on the other hand, is extremely humble and self-effacing. He constantly expresses admiration for other people's expertise and accomplishments, constantly acts as if he thinks they're much sharper than he is, constantly seems awed thy their jobs, their houses, their cars, their shoes. Part of it, of course, is shtick: Columbo throws suspects off guard by pretending to be dumb, so they'll relax too much and tumble into the traps he sets for them. But part of it, I think, is sincere. Even when he suspects people of murder, I think he's often genuinely impressed by their knowledge and talents.

Clearly, he doesn't mind letting people underestimate him, doesn't mind letting them think they're more important than he is. Even his trademark "one more thing" seems like an acknowledgment of his inferior status: The people he's pestering are so superior that he hates to take up their valuable time. The most he can hope for is that they'll indulge him for just a few moments more. Would Holmes be so comfortable about letting others regard him as inferior? I don't think so. I think it would drive him crazy. But Columbo has more democratic attitudes. He doesn't need to have everybody see him as the smartest person in the room. If they see him as no more than a regular guy, or even as less than that, that's fine with him.

What's more, I think Columbo honestly sees himself as a regular guy. When he describes his approach to detection, he doesn't talk about his brilliance. He's not so taken with his deductive powers that he thinks he can rely on those alone. No, he attributes his success to things Americans traditionally value, such as hard work. In "The Bye-Bye Sky High I.Q. Murder Case," Columbo talks to a man (the murderer, as Columbo already suspects) who belongs to a Mensa-type organization: