On Tuesday, June 14, Open Road Media and MysteriousPress.com will release eight e-books toward

what will eventually become the complete Collected Case Files of the Continental Op, edited and presented by Hammett’s

biographer Richard Layman and his granddaughter Julie M. Rivett. As Rivett

notes in her foreword, the series marks “the first electronic publication of

Dashiell Hammett’s collected Continental Op stories to be licensed either by

Hammett or his estate—and the first English-language collection of any kind to

include all twenty-eight of the Op’s standalone stories.” Additionally, the

complete series will include the never-before-published “Three Dimes,” a

fragment of an Op story from the Hammett archive.

Rivett and Layman have worked together on many projects,

including The Hunter and Other

Stories, Return of the Thin Man, The

Selected Letters of Dashiell Hammett: 1921-1960, and Dashiell Hammett: A Daughter Remembers. Rivett speaks widely

about her grandfather’s work and legacy, and I’m honored to welcome her to

SleuthSayers to discuss this landmark project.

ART TAYLOR: Hammett’s

characters Sam Spade and Nick and Nora Charles have surely entered the wider

cultural consciousness more completely, but the Continental Op might arguably

be the more seminal character in terms of the development of the genre. What do

the Op and his stories offer crime fiction readers that The Maltese Falcon, for example, doesn’t?

JULIE M. RIVETT: The Op is important and, yes,

seminal. Ellery Queen said he could have

been Sam Spade’s older brother, equally hardbitten, but with perhaps less

spectacular presentation. The Op’s narratives are workmanlike, realistic, and

procedurally detailed. His plainspoken wit is at least as dry as Spade’s. It’s

a shame he’s not memorialized in film the way that Sam and Nick and Nora are. I

think that’s the main reason the Op is less well known to contemporary readers.

One of other the big differences between the

Op and Spade, Nick, and Ned Beaumont is that he’s a company man, on the payroll

for the Continental Detective Agency, modeled on Pinkerton’s National Detective

Agency, where my grandfather worked for some five years, off and on. Spade and

Nick Charles are independent sleuths. Ned Beaumont functions as a detective,

but in fact he’s a political operator inadvertently entangled in a murder.

Professional standpoint makes a difference in how each one perceives his professional

obligations. The Op is the only one who has to answer to a boss, the Old Man. He fudges his reports at times to cover up

some less than conventional tactics, but, still, he’s loyal to the Agency and he

loves his job. Or he is his job. That

idea of profession as identity runs all through my grandfather’s work. The Op

tales offer an extended narration of workaday professionalism in action.

Several collections in

recent years have featured Continental Op stories, notably 1999’s Nightmare Town and then more extensively

the Library of America’s Crime Stories

& Other Writings in 2001, but this is the first time all of the

standalone Op stories have been gathered together in series form. What might

readers learn about the Op or about Hammett—and what did you yourself take away—from

reading these complete case files, finally gathered in chronological order?

Any careful reader will see the progression

in Hammett’s work. The stories grow longer and more fluid, the Op more

emotionally vulnerable, the resolutions keyed more to justice than law. There’s

evidence of both character and story development. Rick does a good job in his

introductions of describing shifts in the degrees of violence that take place

under Hammett’s three editors at Black

Mask—very little under George W. Sutton, with scanty gunplay; much more

under Philip C. Cody, the Op tempted to go blood simple; and ample

well-developed action under Joseph Thompson Shaw, purposeful as well as

thrilling.

I’m drawn to that biographical potential of

the collection, of course. The complete run of stories offers a fascinating

opportunity to contextualize the Op’s narratives within Hammett’s real life

story. My grandfather starts with a novice’s attention his editors’ demands—thrilled

to be published, but also intent on keeping food on the family table. He hits

his stride with some great stories, but then there’s a break, when he walks

away in anger, deciding to give up on fiction. Then he’s back, with stories

more confident, complicated, and ambitious. He’d realized his talents and was ready

(with Joseph Shaw’s support) to challenge pulp- and crime-fiction norms. And

then the sea change in February of 1930—the final Op story published in Black Mask, the same month that The Maltese Falcon was released by in

hardback by Knopf. With that, my grandfather was done with the Op and off to

explore other possibilities.

A few of the Op

stories have been elusive except in much older editions—“It” and “Death and

Company,” specifically. Why have those not been republished more recently, and

do you anticipate they will be among the standout gems here for readers who are

already fans?

The Op’s publishing history is complex—even

frustrating. I don’t know why those two stories have been overlooked for so

long. There is a gruesome tinge to each, but nothing sufficient to repel

Hammett readers. I certainly can’t explain Lillian Hellman’s choices while she

controlled the estate or the decisions made by her former trustees after her

death. I do know that contracts let

under their tenure made the publication of Complete

Case Files extraordinarily difficult. It seemed ridiculous to me that the

Op’s tales couldn’t be collected altogether! Rick and I are both current trustees

for Hammett’s literary property trust (under Hellman’s will, no less) and even

with that, it was a struggle to assemble all the pieces. We’re hugely pleased

and proud of that we were, finally, able to bring together the Op’s complete

short-story canon.

“It” and “Death and Company” were last

available, alongside many other Op stories, in paperbacks edited by Ellery

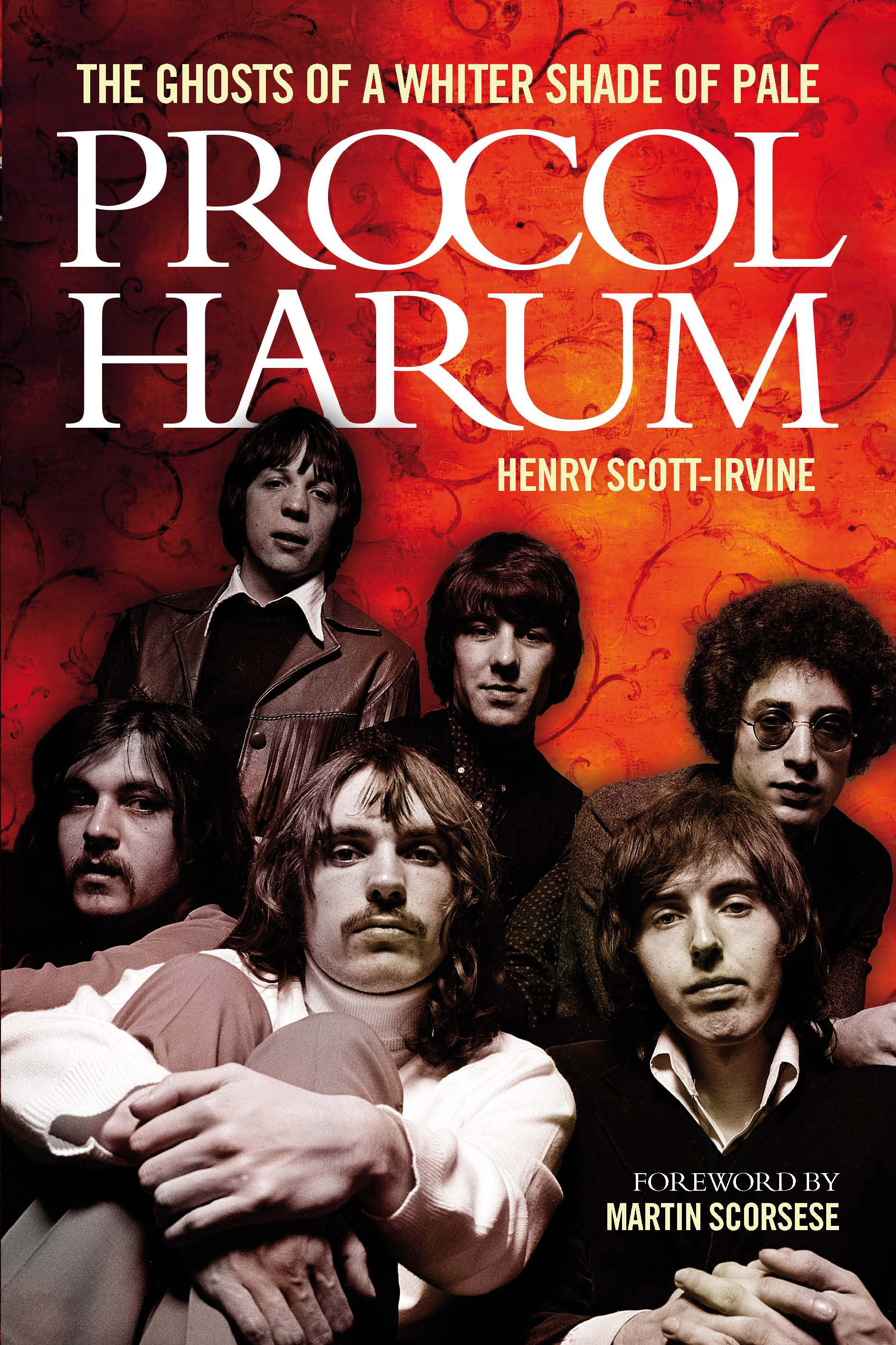

Queen between the early 1940s and early ’50s [the cover to one of those paperbacks can be seen at left]—but you note that the stories in

those editions were presented in “sometimes liberally re-edited form.” [Editorial note: Don

Herron at “Up and Down These Mean Streets” has been less diplomatic, using the word “butchered,” and Terry Zobeck has meticulously charted the editorial changes to “Death and Company” here.] In the newly collected case files, do you and Layman restore these and other stories to their original form?

“It” and “Death and Company” were last

available, alongside many other Op stories, in paperbacks edited by Ellery

Queen between the early 1940s and early ’50s [the cover to one of those paperbacks can be seen at left]—but you note that the stories in

those editions were presented in “sometimes liberally re-edited form.” [Editorial note: Don

Herron at “Up and Down These Mean Streets” has been less diplomatic, using the word “butchered,” and Terry Zobeck has meticulously charted the editorial changes to “Death and Company” here.] In the newly collected case files, do you and Layman restore these and other stories to their original form?

Yes, absolutely! Rick and I worked from copies

of the original publications for each story—26 in Black Mask, and one each in True

Detective Stories and Mystery Stories

magazines. Our only changes are corrections to obvious typos—which were more

common than you might imagine, especially in the earlier editions of Black Mask. The proofreading was

grueling. But we wanted to stick as close to Hammett’s originals as possible

and when in doubt, we left questionable text unaltered. Unlike Ellery Queen,

our first principle was “do no harm.”

Does each of the

eight volumes feature its own individual introductions by you and Richard

Layman?

Here’s how the organization works. Two or

three stories are clustered into each volume. Then the volumes are collected

into three sections: the Early, Middle, and Later Years. Rick wrote introductions for each of the

three sections based on Hammett’s experiences under his three editors at Black Mask, George W. Sutton, Philip

Cody, and Joseph Thompson Shaw. A Sutton, Cody, or Shaw introduction opens each

volume, as appropriate. My foreword traces the publishing and cultural history

of the Op from creation through this most recent publication. Every volume opens with the same foreword. A

separate headnote introduces the never-before-published Op fragment, “Three

Dimes.”

Rick and I have worked together since 1999

and this is our fifth published collaboration. We’ve learned to divvy up the editorial

tasks. Each book has had its own rewards and challenges. In this case, in

addition to constraints imposed by previous contracts, we’re negotiating the

relatively new world of e-publication. It’s

complicated. For now, we’re releasing eight volumes, which include 23 stories.

We hope to release the remaining handful and the fragment later this year.

“Three Dimes” promised to be a real highlight of the

collection here. What more can you tell us about it?

The fragment comes from Hammett’s archive at

the University of Texas at Austin. It is unique—a 1,367-word partial draft, in

the classic Op style, that leaves us wondering what would have happened next

and why the story was set aside unfinished. My grandfather, who saved very

little, saved this, along with chapter and character notes, which will be

included. I think that rare glimpse of Hammett’s process is going to be a real

thrill for fans. Watch for it!

Find out more about the Complete Continental Op here at Open Road Media.

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-1762406-1423414664-1583.jpeg.jpg)