Mystery short stories offer

us many pleasures, including the opportunity to enjoy,

briefly, the company of protagonists who might drive us crazy if we

tried to stick with them through an entire novel. I was reminded of this

truth recently when I reread a Dorothy L. Sayers story featuring

Montague Egg, a traveling salesman who deals in wines and spirits. Most

Sayers mysteries, of course, center on another protagonist, Lord Peter

Wimsey. As almost all mystery readers know, Lord Peter is highly

intelligent, unusually observant, and adept at figuring out how

scattered scraps of information come together to point to a conclusion.

Montague Egg fits that description, too. Both characters are engaging

and articulate, both have exemplary manners, and both sprinkle their

statements with lively quotations. More important, both Lord Peter and

Montague Egg abide by codes of honor, and both are devoted to the cause

of justice, to identifying the guilty and exonerating the innocent. And

Sayers evidently found both protagonists charming: She kept returning to

them for years, writing twenty-one short stories about Lord Peter,

eleven about Montague Egg.

But while Sayers also wrote eleven novels about Lord Peter,

she didn't write a single one about Montague Egg. I don't know if she

ever explained why she wrote only short stories about him--I checked two

biographies and didn't find anything, but there might be an explanation

somewhere. In any case, it's tempting to speculate about what her

reasons might have been.She

might have thought Egg lacks the depth of character needed in the

protagonist of a novel. That's true enough, but she could always have

developed his character further, given him more backstory. She did that

with Lord Peter, who's a far more complex, tormented soul in

Gaudy Night and

Busman's Honeymoon than he is in

Whose Body?

Or perhaps she thought all the little quirks that make Montague Egg

such an amusing, distinctive short story protagonist would make him hard

to take if his adventures were stretched out into a novel. Yes, Lord

Peter has his little quirks, too, but I think his are qualitatively

different. For example, while Lord peter tends to quote works of English

literature in delightfully surprising contexts, Montague Egg sticks to

quoting maxims from the fictional

Salesman's Handbook, such as

"Whether you're wrong or whether you're right, it's always better to be

polite." Three or four of these common-sense rhymes add humor to a quick

short story. Dozens of them might leave readers wincing long before a

novel ends.

I did plenty of wincing when I decided, not long ago, to read Anita Loos'

Gentlemen Prefer Blondes

(not a mystery, but protagonist Lorelei Lee does go on trial for

shooting Mr. Jennings, so I figure I can sneak it in as an example). For

the first thirty pages or so, I relished it, laughing out loud at

Lorelei's uninhibited voice, at the absurd situations, at the appalling

but flat-out funny inversions of anything resembling real values. Before

long, however, I was flipping to the back of this short book to see how

many more pages I had to read before I could declare myself done.

Lorelei's voice, which had been so entertaining at first, had started to

get on my nerves, and her delusions and her shallowness were becoming

hard to take. I couldn't understand why this book had been so wildly

popular until I found out it had originally been a series of short

stories in

Harper's Bazaar. Well, sure. A small dose of Lorelei

once in a while can be enjoyable, but spending hours with her is like

getting stuck talking to the most self-centered, superficial guest at a

party. If you ever decide to read

Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, I recommend reading it one chapter at a time, and taking at least a week off in between.

There

could be all sorts of reasons that a protagonist might be right for

short stories but wrong for novels. I wrote a series of stories (for

Alfred Hitchcock's Mystery Magazine)

about dim-witted Lieutenant Walt Johnson and overly modest Sergeant

Gordon Bolt. Everyone--including Bolt--sees Walt as a genius who cracks

case after difficult case. In fact, Walt consistently misunderstands all

the evidence, and it's Bolt who solves the cases by reading deep

meanings into Walt's clueless remarks. A number of readers urged me to

write a novel about this detective team. (And yes, you're right--most of

these readers are members of my immediate family. They still count as

readers.)

Despite

my fondness for Walt and Bolt, though, I never even considered writing a

novel about them. I think they're two of the most likable, amusing

characters I've ever created. But Walt is too dense, too anxious, and

too cowardly to sustain a novel. How long can readers be expected to put

up with a detective who's always confused but never scrapes up the

courage to admit it, no matter how guilty he feels about taking credit

for Bolt's deductions? And while I find Bolt's self-effacing admiration

for Walt sweet and endearing, I think readers would get fed up with his

blindness before reaching the end of Chapter Two.

I

think these two are amusing short-story characters precisely because

they're locked into patterns of foolish behavior. As Henri Bergson says

in

Laughter, repetition is often a fundamental element in comedy.

But this sort of comedy would, I think, get frustrating in a novel.

Readers expect the protagonists in novels to learn, to change, to grow.

Walt and Bolt can't learn, change, or grow without betraying the premise

for the series. So I confined them to twelve short stories, spread out

between 1988 and 2014. In the story that completed the dozen, I brought

the series to an end, doing my best to orchestrate a finale that would

leave both characters and readers happy--a promotion to an

administrative job for Walt, so he can stop pretending he's capable of

detecting anything, and a long-awaited wedding and an adventure-filled

retirement for Bolt. I truly love these characters. But I'd never trust

them with a novel.

Other

short-story protagonists, though, do have what it takes to be

protagonists in novels, too. Lord Peter Wimsey is one example--in fact,

most readers would probably agree that, delightful as most of the

stories about him are, the novels are even better. Sherlock Holmes is

another example--four novels, fifty-six short stories, and I think it's

fair to say he shines in both genres. I considered one of my own

short-story protagonists so promising that I decided to build a novel

around her. Before I could do that, though, I had to make some major

changes in her character.

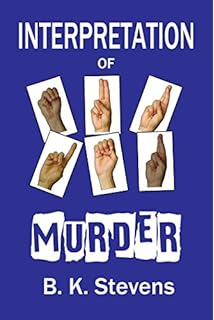

American Sign Language interpreter Jane Ciardi first appeared in a December, 2010

Alfred Hitchcock's Mystery Magazine

story, now republished as a Kindle story called "Silent Witness."

Positive responses to the story--including a Derringer from the Short

Mystery Fiction Society--encouraged me to think I might be able to do

more with the character. It also helped that one of my daughters is an

ASL interpreter who can scrutinize drafts and provide insights into deaf

culture and the ethical dilemmas interpreters face. And I like Jane.

She's smart, she's observant, she has acute insights into human nature,

and she has a strong sense of right and wrong. In "Silent Witness," when

she interprets at the trial of a deaf man accused of murdering his

employer, she wants the truth to come out. She definitely doesn't want

to see an innocent man go to prison.

But

the Jane Ciardi of "Silent Witness" is mostly passive. She's sharp

enough to figure out the truth and to realize what she should do, but

she lacks the courage to follow through. Her final action in the story

is to fail to act, to sit when she should stand, to convince herself

justice will probably be done even if she remains silent. I think all

that makes Jane an interesting, believable protagonist in a short story

that raises questions it doesn't quite answer.

I don't

think it's enough to make her a fully satisfying protagonist in a

novel--at least, not in a traditional mystery novel. In what's often

called a literary novel, the Jane of "Silent Witness" might do

fine--another protagonist paralyzed by doubt, agonizing endlessly about

right and wrong but never taking decisive action. The protagonists of

traditional mysteries should be made of sterner stuff. So in

Interpretation of Murder,

I made Jane regret and learn from the mistakes she'd made in "Silent

Witness." We find out she did her best to correct them, even though it

hurt her professionally. And when she's drawn into another murder case,

she works actively to uncover the truth, she comes up with inventive

ways of gathering evidence, and she speaks out about what she's

discovered even when situations get dangerous. I can't be objective

about Jane--others will have to decide if these changes were enough to

make her an effective protagonist for

Interpretation of Murder.

But I'm pretty sure mystery readers would find the Jane of "Silent

Witness" a disappointing companion if they had to read an entire novel

about her.

Have you encountered mystery characters who are effective

protagonists in short stories but not in novels--or, perhaps, in novels

but not in short stories? If you're a writer, have you decided some of

your protagonists work well in one genre but not in the other? If you've

used the same protagonist in both stories and novels, have you had to

make adjustments? I'd love to hear your comments.