"I can't access the fingerprint files," Phil said.

Sally fisted her hair. "Oh, no! That could negatively impact our investigation!"

Should I contact the lieutenant?" Fred asked.

"I'm efforting that right now," Phil assured him.

In this brief but thrilling bit of dialogue, I have verbed five nouns.

That is, I have taken five words once firmly ensconced in the language

as nouns, and I have used them as verbs. This sort of verbing

seems to be going on a lot these days. We read newspaper articles about

the benefactor who gifted the museum with a valuable painting, about the county office transitioning to a new computer system. And of course almost all of us speak of texting people and friending people. Some of

us say we Facebook.

Should we accept the verbing trend as inevitable, perhaps desirable? Should we resist it? Does resistance make sense in some cases but not in others? Writers, including mystery writers, probably have some influence on the ways in which language changes, perhaps more influence than we realize. So maybe, before we let ourselves slip into following a linguistic trend, we're obliged to examine it carefully, to think about whether it's a change for the better.

Should we accept the verbing trend as inevitable, perhaps desirable? Should we resist it? Does resistance make sense in some cases but not in others? Writers, including mystery writers, probably have some influence on the ways in which language changes, perhaps more influence than we realize. So maybe, before we let ourselves slip into following a linguistic trend, we're obliged to examine it carefully, to think about whether it's a change for the better.

Obviously, there's nothing unusual or improper about a word functioning as more

than one part of speech. "He decided to turn off the ceiling light and

light the candles, while his wife, wearing a light blue dress, fixed a

light supper." Here, in one sentence, "light" serves as noun, verb,

adverb, and adjective--repetitive, but not ungrammatical or unclear. And I think we'd all agree language is a living thing that needs to change

to meet new needs. Many would argue (and I'd agree) that the English

language, especially, is vital and expressive precisely because it's

always been so flexible and open, so ready to absorb useful words from

other languages and to adjust to changing conditions. Sometimes, change

means inventing new words to describe new things--telephone, astronaut,

Google. Sometimes, it means using existing words in new ways--text,

tablet, tweet. These sorts of changes in the language reflect changes in reality. Some of them may enrich the language; some may make it sillier or less euphonious. Either way, trying to resist them is probably pointless.

Is verbing such a change? In some cases, I think, it probably is. Consider the first sentence in the opening dialogue. "Access" used to be a noun and nothing but a noun. Fowler's Modern English Usage (I've got the second edition, published in 1965, inherited from my English professor father) draws careful distinctions between access and accession, showing scorn for those who "carelessly or ignorantly" confuse the two. Fowler doesn't even consider the possibility that anyone might use "access" as a verb. One might need a key to gain access to the faculty washroom, but the idea that anyone might access the washroom--no. Today, though, when almost all of us use computers and often have trouble getting at what we want, using "access" as a verb seems natural. Yes, Phil could say he can't gain access to the fingerprint files, but the extra words feel cumbersome here, an inappropriate burden on a process that should take seconds. Old fashioned as I am, I think using "access" as a verb might be a sensible, useful adjustment to change.

Back to the opening dialogue: Sally fears not being able to access the fingerprint files "could negatively impact our investigation." I think some writers use "impact" as a verb because, like "fist," it sounds sexy and forceful, sexier and more forceful than "affect" or "influence." But does it convey any meaning those words don't? If not, I'm not sure there's an adequate reason for creating a new verb. And if we have to modify "impact" with an adverb such as "negatively" to make its meaning clear, wouldn't it be more concise to choose a specific one-word verb such as "hurt" or "stall"--or "end," if the negative impact will in fact be that bad? Again, I'd say "impact" is a verb we can do without. It answers no need our existing verbs fail to meet. It adds nothing to the language.

What about "contact"? In the opening dialogue, Fred asks if he should "contact" the lieutenant. Like "access," "contact" was once a noun and nothing else. Is there a problem with using it as a verb as well? Strunk and White think so. In the third edition of Elements of Style (a relic from my own days as an English professor), they (or maybe just White) declare, "As a transitive verb, [`contact'] is vague and self-important. Do not contact anybody; get in touch with him, or look him up, or phone him, or find him, or meet him." Or, in this situation, Fred might ask if he should inform the lieutenant, or warn her, or ask her for advice. "Contact" is pretty well established as a verb by now, but I think the argument that it's "vague and self-important" still holds. "Contact" is a lazy verb. It doesn't meet a new need--it just spares us the trouble of saying precisely what we mean. Even if few readers would object to using "contact" as a verb these days, writers who want to be clear should still search for a more specific choice.

Then there's "effort." What possible excuse can there be for transforming this useful noun into a pretentious verb? In the second edition of Common Errors in English Usage (a wonderful resource), Paul Brians declares such a transformation "bizarre and unnecessary": "You are not `efforting' to get your report in on time; you are trying to do so. Instead of saying `we are efforting a new vendor,' say `we are trying to find a new vendor.'" Maybe some people think "efforting" will make it sound as if they're working harder. If so, they can always say they're "striving" or "struggling"--but those words will be obviously inappropriate if not much work is actually involved, if they're just making a phone call. Is "efforting" appealing because it lets us get away with making simple tasks seem more arduous than they really are? If so, we should definitely resist the temptation to inflate the importance of what we're doing by using a fancy new verb.

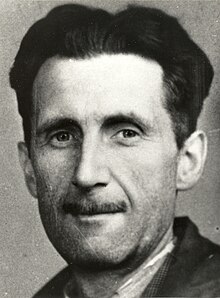

By now, some may be wondering if any of this matters. If we want to dress up our sentences by turning some nouns into impressive-sounding new verbs, so what? Where's the harm in that? George Orwell provides an answer in his classic "Politics and the English Language." I can't summarize his subtle, complex argument here; I can only offer a quotation or two and urge anyone who hasn't already read the essay to do so. Just as ideas can influence language, Orwell argues, language can influence ideas. The English language "becomes ugly and inaccurate because our thoughts are foolish, but the slovenliness of our language makes it easier for us to have foolish thoughts." Nor should we surrender to damaging trends in language because we assume resistance is futile. "Modern English, especially written English," Orwell says, "is full of bad habits which spread by imitation and which can be avoided if one is willing to take the necessary trouble." As writers, perhaps we have a special responsibility to protect the language by setting a good example. At least we can effort it.

Oops. Sorry. At least we can try.

![Pageflex Persona [document: PRS0000037_00019] Pageflex Persona [document: PRS0000037_00019]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEi-MHEB0RUlCWSkHVPsRCVV7EdXADjGa-vYPhWVbu9YqxmKw93vWWko7IrjOvRgdbQ_IbMVt9X4OQpQlP_8Ikfi205UaopK7fC7wwOeRC6lwbg6J6N8qpq6AGwg2MTFyHzQhq-IvscU_44/?imgmax=800)