For years now, anytime I'm the focus of a Q&A session--at a conference, booksigning, writers' meeting, wherever--I'm asked to address some of the same questions. The most-often-asked so far has been, without fail, "Where do you get your ideas?" (It would seem that I'd have a good answer for that one by now, at least an answer better than the old "ideas are everywhere." But I don't.)

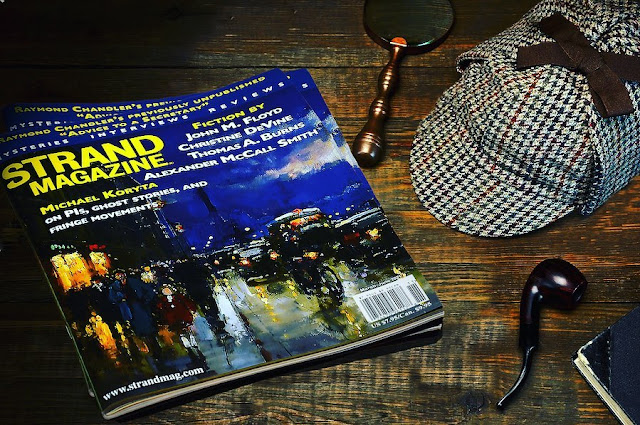

Two more often-asked questions always surprise me a bit, because they deal not with writing style or writing processes but with two specific markets. Many of my fellow writers, whether we already happen to know each other or not, ask what tips I might have for submitting short stories to (1) Woman's World and (2) Strand Magazine.

On the one hand, they're fair questions. I've been fortunate at both publications ever since I sold my first stories there, which happened in the same year: 1999. On the other hand, as all you writers know, any answer to "How do I sell stories to a certain market?" is as difficult and subjective as the answer to "Where do you get your ideas?"

Stranded in Storyland

Since I've attempted in several different SleuthSayers posts (here's one of them, from a year ago) to steer writers in the right direction with regard to writing mysteries for Woman's World, I decided to try, today, to do the same kind of thing with Strand Magazine. Bear in mind that the very best way to learn what stories a market likes, whether it's The Strand or WW or anyplace else, is to read the stories in the magazine--but failing that, or maybe in addition to it, I hope this might be of at least some help. Bear in mind also that I don't have all the answers. I still get rejections too, even after all this time, from both these markets.

Having said all that . . . what I've done is put together a list of the stories I've sold to The Strand so far, along with their wordcounts, a quick summary of each story, the types of crimes that were involved, and, as an afterthought, some notes about any later recognition given to those stories. (It's a fact that stories published in The Strand often show up in annual best-of anthologies and award-nomination lists.) And after that I'll talk about some other submission pointers.

So here are my Strand stories. I can't guarantee that you'll be published there if you write stories of similar length and with similar plots and crimes, but I can tell you what has worked for me.

"The Proposal" -- About 4600 words. A Texas oilman who's being blackmailed discovers a way out of his dilemma. The type of crime: murder. This story was later named as one of the year's "Other Distinguished Stories" in Best American Mystery Stories 2000.

"Murphy's Lawyer" -- 2400 words. An engineer for a chemical company convinces an attorney to help him fake a laboratory accident. The crimes: murder, insurance fraud.

"Debbie and Bernie and Belle" -- 4500 words. A lovesick law student enlists the help of a mysterious ten-year-old girl to try to repair a break-up with his fiancee. The crime: robbery.

"Reunions" -- 4100 words. Two airline travelers, one of them on a secret mission, meet and then drift apart, neither realizing they'll soon meet again. The crime: murder.

"Turnabout" -- 4800 words. A highway rest-stop near the site of a recent bank robbery soon becomes a battleground. The crimes: robbery, murder. Named as one of the year's "Other Distinguished Stories" in Best American Mystery Stories 2012.

"Bennigan's Key" -- 4400 words. When mob employee George Bennigan is rewarded with a vacation to a remote island resort, he finds himself wondering about the possible reasons. The crime: murder.

"Blackjack Road" -- 4000 words. Two loners--one a convict, the other a man considering suicide--are thrown together in a chance meeting. The crimes: prison escape, murder.

"Secrets" -- 3200 words. Two ferry passengers with dark secrets discover a surprising and deadly connection. The crime: murder.

"200 Feet" -- 4400 words. One man, one woman, and a narrow ledge on the side of building twenty floors above the street. The crime: murder. Nominated for an Edgar in 2015.

"Molly's Plan" -- 5000 words. Most successful bank robberies are simple. Owen McKay's was not. The crime: robbery. Selected for inclusion in Best American Mystery Stories 2015.

"Driver" -- 9500 words. When a U.S. senator's missteps lead to what could be a career-ending scandal, only one person can save him: his limo driver. The crimes: blackmail, fraud, murder. Won a 2016 Derringer Award and was named as one of the year's "Other Distinguished Stories" in Best American Mystery Stories 2016.

"Arrowhead Lake" -- 7500 words. A robbery in a hi-tech company's remote headquarters comes down to a battle using primitive weapons. The crimes: murder, robbery, manslaughter.

"A Million Volts" -- 4500 words. Two romantic affairs on a college campus turn violent. The crimes: murder, assault, terrorism.

"Jackpot Mode" -- 7900 words. A pair of ATM experts--one in software, one in hardware--attempt to steal a small fortune from a local bank. The crime: robbery. Named as one of the year's "Other Distinguished Stories" in Best American Mystery Stories 2017.

"Flag Day" -- 6500 words. The employees of a suburban ice-cream shop stage a false theft in order to hide a real and bigger one--and run into problems. The crime: robbery.

"Crow Mountain" -- 4100 words. A handicapped fisherman encounters an escaped convict in the middle of nowhere. The crimes: prison escape, murder.

"Foreverglow" -- 2400 words. Two young sweethearts plan the heist of a special jewelry exhibit from a local department store. The crime: robbery.

"Lucian's Cadillac" -- 2400 words. Many years after their graduation, three classmates come together to fight an old enemy. The crime: murder.

"Biloxi Bound" -- 4800 words. Two cafe owners in a crime-infested city neighborhood decide to relocate . . . but not soon enough. The crimes: murder, robbery. Selected for inclusion in Best Mystery Stories of the Year 2021 and in Best Crime Stories of the Year 2021.

"The Ironwood File" -- 3100 words. A tyrannical boss, an employee, and a former employee bent on revenge converge one day in a downtown office building. The crimes: industrial negligence, attempted murder, sexual harassment.

"Nobody's Business" -- 2300 words. Two strangers--a man fleeing from his debts and an old woman hunting alligators--team up in the woods against other kinds of varmints. The crimes: loan-sharking, murder.

"The Road to Bellville" -- 6200 words. A female sheriff transporting an inmate between prisons stops for a break at the wrong roadside cafe. The crimes: robbery, prison escape, murder.

"Sentry" -- 6700 words. Private investigator Tom Langford hires on as a bodyguard to the wife of a mob boss. The crimes: murder, racketeering.

Other info

For what it's worth, none of the above stories were locked-room mysteries, none were whodunits, none had supernatural elements, only one was a PI story, none were written in present tense, and they're pretty equally divided between first-person and third-person POV. Also, all of them were contemporary crime stories, not historicals, BUT this market does seem to like Sherlock Holmes stories and historical mysteries.

As for other submission pointers, remember that The Strand usually doesn't publish stories with otherworldly elements, although its guidelines say they'll consider them, and they frown on too much sexual content and strong language. Another thing: they prefer stories of between 2000 and 6000 words. The guidelines say they're occasionally receptive to stories of less than 1000 words as well, and my own experience has shown me they'll sometimes take stores longer than 6000--see my list, above. You'll also see that the first ten stories I sold them were safely in that 2000-6000 range, so I wasn't taking any chances; after that I tended to sneak in much longer stories now and then.

One of the biggest things to keep in mind is that The Strand almost never responds to a submission unless it's with an acceptance. That means that you must keep close track of your submissions--something you're probably doing anyway--and that after a reasonable wait (three months or so, in my opinion) you should probably withdraw a story that hasn't gotten a response and submit it elsewhere. Woman's World works the same way.

Last but not least, The Strand's editor is Andrew F. Gulli and the submission email address is submissions@strandmag.com.

Have any of you tried sending stories to The Strand? Any successes? Anything you can add to the observations I've made? As always, comments are welcome.

I hope this helps. If you do choose to submit a story there, best of luck!

This subject has been on my mind because of a story I have in the current issue of Mystery Magazine. The protagonist of "Kill and Cure" is trying to find out who killed a college student. He is doing so on behalf of the young man's mother.

This subject has been on my mind because of a story I have in the current issue of Mystery Magazine. The protagonist of "Kill and Cure" is trying to find out who killed a college student. He is doing so on behalf of the young man's mother.