"The development of full artificial intelligence could spell the end of the human race." Stephen Hawking

“With artificial intelligence we are summoning the demon. In all those stories where there’s the guy with the pentagram and the holy water, it’s like – yeah, he’s sure he can control the demon. Doesn’t work out." Elon MuskNow I can sort of understand why. The general premise for decades has been that some day the computers/robots will take over, and run us, with only two possible scenarios:

- Great - Robots and computers will do everything for us, and we will live a life of luxury (according to the late great Frederick Pohl, too much so), comfort and security thanks to Isaac Asimov's Three Laws of Robotics that protect mankind from the revolt of the machines.

- Bad - Everything by Philip K. Dick, and, of course, "The Matrix".

Look, the main reason we have computers and robots is to do our work for us. Anything boring, repetitive, heavy, dangerous, etc. - eventually, we'll make a machine to do it. Calculators mean I don't have to add up the columns of figures for which they used to hire Nicholas Nickleby. Payloaders mean we don't need an army of physical laborers hoisting earth. Tractors, etc., mean that today's Pa Ingalls doesn't need to muscle his way through the sod with horse and plow. Computers mean I don't have to write everything out long-hand, or type it over and over again until it's perfect. It's great.

Look, the main reason we have computers and robots is to do our work for us. Anything boring, repetitive, heavy, dangerous, etc. - eventually, we'll make a machine to do it. Calculators mean I don't have to add up the columns of figures for which they used to hire Nicholas Nickleby. Payloaders mean we don't need an army of physical laborers hoisting earth. Tractors, etc., mean that today's Pa Ingalls doesn't need to muscle his way through the sod with horse and plow. Computers mean I don't have to write everything out long-hand, or type it over and over again until it's perfect. It's great.  On the other hand, modern technology has eliminated and is eliminating a whole ton of jobs. Typesetters; typists; clerks; gas station attendants; innumerable factory workers; graphic designers; paralegals; low-level tax preparers; most farm hands; most farmers; bank tellers; airline check-in agents; retail clerks; accountants; actuaries; travel agents; most reporters, etc. Soon there will be far fewer surgeons, teachers, and other high-level jobs as robots take over. And in the fast food industry, the robots are coming to flip those burgers and make those fries.

On the other hand, modern technology has eliminated and is eliminating a whole ton of jobs. Typesetters; typists; clerks; gas station attendants; innumerable factory workers; graphic designers; paralegals; low-level tax preparers; most farm hands; most farmers; bank tellers; airline check-in agents; retail clerks; accountants; actuaries; travel agents; most reporters, etc. Soon there will be far fewer surgeons, teachers, and other high-level jobs as robots take over. And in the fast food industry, the robots are coming to flip those burgers and make those fries.The point is that, as we use technology to do 40, 50, 60, 70, 80, 90% of the work, we will also unemploy a significant number of people. There will still be jobs, at all levels - just infinitely less of them. Perhaps only a handful, here and there. Which leaves the elephant in the room: what do you do about the people?

Yes, everyone talks about retraining. See a typical chirpy article on "The Future of Work" . BUT, I've always had two basic questions:

(1) There is a significant number of people who can't be retrained. Some will be too old, some will be too set, and some - frankly - whose mental ability to learn complex problem-solving skills is extremely limited. I run into some of them at the pen. (In case you don't know it, prisons are the modern housing facility for many of the mentally disabled, as well as the mentally ill.) These are the people who are never considered in future planning talks, the ones that are ignored by all economists and pundits, but shouldn't be. As I once said about a former student who was caught stealing, "Well, how else is he going to make a living?"

(1) There is a significant number of people who can't be retrained. Some will be too old, some will be too set, and some - frankly - whose mental ability to learn complex problem-solving skills is extremely limited. I run into some of them at the pen. (In case you don't know it, prisons are the modern housing facility for many of the mentally disabled, as well as the mentally ill.) These are the people who are never considered in future planning talks, the ones that are ignored by all economists and pundits, but shouldn't be. As I once said about a former student who was caught stealing, "Well, how else is he going to make a living?" (2) If you have 250 people in a town, and there are only 100 actual jobs, it doesn't matter how much retraining you do. There are still 150 people without work because there are no jobs. Urbanize that. Nationalize that. Globalize that.

In Philip Jose Farmer's "Riders of the Purple Wage", he posited a society in which they coped with the problem of almost complete unemployment by giving everyone a salary just for being born. It's enough to keep them housed and fed and hooked up to the Fido, a combination cable TV/videophone, along with a little wet-ware called a fornixator (you translate it). To get anything else, you have to prove your exceptionality, but most people are happily occupied without it. For those who aren't, well, there are wildlife reserves where they can go off and be weird - but they have to give up the purple wage.

It's a successful society, in its own way - and perhaps the only logical one. Because the truth is, sooner or later, in a society where technology is doing 90% of the work, there will have to be a "purple wage".

It's a successful society, in its own way - and perhaps the only logical one. Because the truth is, sooner or later, in a society where technology is doing 90% of the work, there will have to be a "purple wage". That, or

(1) society comes up with innumerable "make work" jobs, like picking oakum in the workhouse. (Personally, I foresee a lot of crime.)

That, or

(2) the unemployed masses (a la "Soylent Green" or "Zardoz", etc.) will be pounding at the armored enclaves of the fabulously wealthy. (As I said, I foresee a lot of crime.)

That, or

(3) a whole lot of people are going to have to die, leaving just enough to run the machines, and do the few jobs that still cannot be done by machines, and the fabulously wealthy (there is always a group of fabulously wealthy) to enjoy unending leisure. Wall-E, call home!

That, or

(4) The Matrix.

Anyway, here's the question: As we pursue technological advancements, can we let go of the Protestant Work Ethic? Let go of the idea that we are what we do? Must people work or starve, even if there's plenty of everything except jobs? Can we tolerate, support, even design a society where the norm for everyone (instead of just the wealthy) is "the leisured class"?

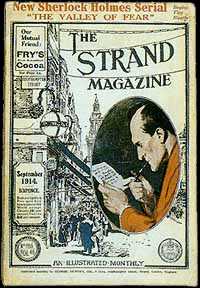

Now, you may think the last question is nonsense. For one thing, we've been promised endless leisure for a century now, and most people are still working their butts off. On the other hand, we do have more leisure than almost any other society in history. This began with the industrial revolution, and one of the most interesting things about reading "Consuming Passions" by Judith Flanders is watching the development of ways for the working classes to spend their new-found leisure. (Hey - they had all of Saturday afternoon and Sundays off!) Thanks to advertising, sports, vacations, theater, and literature were turned into major industries. (Drinking had always been a favorite activity.) And, instantly, the pundits, poets, philosophers, and religious thinkers started decrying the horrible waste of human time and energy on trivia. And talking about the nobility of hard work, piety, thrift, self-denial and sobriety: for the lower classes only, of course.

|

| Victorian cricket team |

We have pretty much the same discussion going on today: in certain circles, if you don't have a paying job, you're worthless. (Unless you're wealthy enough not to.) And the idea that someone who's unemployed has a television, a cell phone, and computer games for the kids - well, they're obviously spending too much money on all the wrong stuff. Not to mention, if they have such things, they can't be "really" poor.

NOTE 1: In Florida they give cell phones to the homeless, for a variety of reasons. (Contact from parole officers, call-backs on jobs, etc.)

NOTE 1: In Florida they give cell phones to the homeless, for a variety of reasons. (Contact from parole officers, call-backs on jobs, etc.) NOTE 2: I'm always amazed at the people who check out other people's grocery carts and then post, outraged, if someone who's on food stamps buys candy or other luxury items. (See this article for the alternative view: People on Food Stamps Make Better Grocery Choices.) God forbid the poor eat something other than gruel...

Basically, I'm leisured, you're lazy, and they're useless.

Anyway, today we've got smart phones, social media, computer games, Netflix, and innumerable other ways to waste what time we have (on the job or off) in the modern equivalent of Fidos and fornixators. And it seems like the list is going to expand at algorithmic rate. Meanwhile, the list of available jobs is decreasing, at least geometrically, every time we turn around. IF we get to where technology performs most of the work, and IF we get to where we have a regular unemployment of 30, 40, 50, 60, 70 percent, can we change our thinking from "unemployed" to "leisured"? Can we develop a new idea of what people "should" do? Of what people are "supposed" to do?

Without work, what are people for?

|

| "Tompkins Square Park Central Knoll" by David Shankbone - David Shankbone, licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons |