Okay, in our last episode, I discussed some of the mistakes I made trying to publish a novel I first conceived in 1972. It changed radically between then and 1980, when I submitted the third complete revision as my sixth-year project at Wesleyan and my advisor encouraged me to send it to publishers… again.

I gained about a dozen more rejections. Soon after the last one arrived, I became heavily involved in community theater for the next twenty-plus years. After 1981, I wrote no fiction until 2003, when I retired from teaching and our theater lost its performance space the same week.

While the theater searched for a new location, I looked at that novel again. For the first time, I took it seriously and read books on writing and marketing fiction. In May 2004, I attended several excellent workshops at the Wesleyan Writers Conference. I even sold some stories that grew from writing prompts in those sessions. And between 2003 and 2007, I wrote four or five more novels, none of which sold, but which kept getting better.

I sent those novels out with a proper query and synopsis (finally, right?). Books that would eventually become Blood on the Tracks, Cherry Bomb, and Who Wrote the Book of Death? gathered 210 rejections among them while I learned more about plotting, pacing, and selling. I set Blood in Detroit because of a chance meeting with a classmate at my high school reunion, and I changed everything except the name of the female protagonist (Megan Traine) several times between 2003 and 2008 because of feedback buried in the 115 rejections.

Cherry Bomb started as Good Morning Little School Girl, a sequel to Blood, but the first half of the story was an incoherent mess. Years later, I moved it to Connecticut and the Berlin Turnpike, a notorious trafficking area, and it worked much better as a Zach Barnes story.

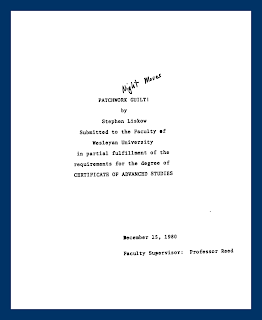

|

| My bound copy of the project. The theater used it as a prop in Bell, Book & Candle, hence the pentagram (not closed) |

By then I'd learned enough about plot and pace to see that the biggest problem with Patchwork Guilt, the name I'd used on the grad school project (I don't remember the other titles before that one) was pace. The story covered most of a school year in chronological order, but the inciting incident didn't occur until January. With nothing at stake, the first half of the book was literary quicksand. I thought resequencing the scenes would solve most of the book's problems, so I broke the MS down as the other WIP taught me to do: I made each scene into a separate word file so I could change the order more easily.

I published Who Wrote the Book of Death? with a small local publisher, but knew none of my other novels would fly with them. They had a maximum word limit of 70K, and I hated their cover and edit. I explored CreateSpace and talked to a theater colleague who designed posters for several plays I directed. He also designed book covers, so I self-published heavily-revised versions of the rejected novels, learning to format more effectively through trial and error.

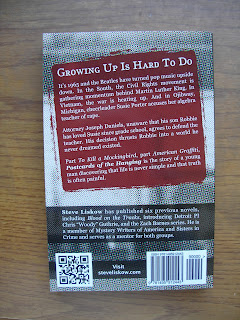

SJ Rozan's Absent Friends showed me how to resequence Patchwork Guilt, and I figured out that giving the date or time of each scene made things clear. I don't remember when I changed the title to Postcards of the Hanging, but the more I thought about it, the more I liked it. It's a line from Bob Dylan's "Desolation Row," from his 1965 LP Highway 61 Revisited, and the story takes place in 1964-65. It's about the scandal and public outrage over a teacher accused of rape. I had originally been inspired by Faulkner's Intruder in the Dust and Lucas Beauchamp, but I was also thinking of a northern version of To Kill a Mockingbird. I graduated from high school in 1965, so the protagonist was a year younger than me. The early drafts changed geography and details from a real scandal my senior year, but the vibe and attitudes were right. Years later, I submitted the finished book to a contest where the judge praised my research and historical accuracy. Well, it wasn't history when I wrote the first draft.

I sent out carefully revised synopses and got another break when an agent told me she didn't handle YA books. I'd never considered the book YA even though the narrator/protagonist was 16, but I saw how my synopsis gave that impression. I needed to fix that.

Hooked by Les Edgerton discusses how to write effective openings, and it gave me the solution. I wrote a prologue and an epilogue that served as a frame story for the rest of the book. When agents or editors asked for the first 25 pages or first few chapters, they got the prologue, then the "real" story, which now opened with the teacher being accused of rape in January.

I think I wrote the prologue and epilogue in 2011. That same year, I self-published The Whammer Jammers. My theater colleague designed the cover and Chris Knopf generously blurbed it. Less than two months later, I republished Who Wrote the Book of Death? with a new cover and a new edit that removed the 800-plus commas my former publisher added. Other revised rejects followed: Cherry Bomb, now moved to Connecticut, Run Straight Down, and eventually Blood on the Tracks, the original Detroit novel under its fourth title and with a protagonist who was no longer a grown-up Robbie Daniels, the protagonist of Postcards.

By then, I understood more about plotting, pacing, and description. Following Rozan's example, I added dates to the individual scenes and threaded flashbacks through the present action, layering in the clues and character work.

My biggest surprise was that I rewrote almost nothing in the 30-year-old text. I added the prologue and epilogue, and I changed the order of the scenes, but I only added one transition scene (about three paragraphs), cut some of the original opening exposition, and expanded two scenes late in the book. That's all. I don't think I even rewrote any of the dialogue. I took that as a sign that I'd been on the right track all those years before.

I self-published the book in 2014, 42 years after starting the first draft.

I still have a lot to learn, but I think I finally got that one right.

.jpg)