|

| C.L. Pirkis's Loveday Brooke |

Even in 1912: You've come a long way, baby—right? Toss us a pack of Virginia Slims—from 1968.

|

| Pauline Hopkins |

What's interesting about Hopkins, however, is that even as she explores racial attitudes and gender issues with a progressive's eye, her story is more conservative on other issues, somewhere at the intersection of class, intellect, and morality—and Hopkins herself seemed to be so as well, advocating elsewhere the "amalgamation" of the races as a way to bring down racial barriers, but also stressing that it was the "worthy" blacks and white intermingling which would improve civilization, while those unworthy ones... well, as critic Sigrid Anderson Cordell explained it in a fascinating 2006 essay on Hopkins' work, those unworthy ones would be "'civilized' or removed from the gene pool."

Even in texts without the racial elements, my student saw that attention to gender equality often parted ways quickly with concerns about class inequality. Lady Molly and her companion in the Female Department were quick to dismiss men's attitudes and achievements, but the story was equally quick to villainize women of the lower-classes for greed and for sexual promiscuity—"slut shaming" them, as one of my students put it.

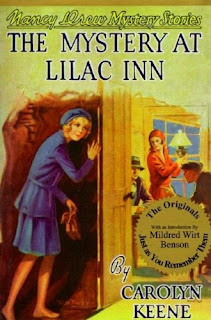

Much of this discussion came to a head this week as we discussed Nancy Drew—everyone's favorite girl sleuth (or nearly everyone's; see SleuthSayer B.K. Stevens' terrific dissent here).

As an icon perhaps even more than as a character, Nancy can—and certainly has—been celebrated from a number of feminist perspectives, from her first appearance still in the shadow of the 19th Amendment's ratification (just a decade before) and right up til today. As Priya Jain writes in her 2005 Salon essay "The Mystery of a Feminist Icon," Nancy was "a model citizen with a perfect balance of toughness and femininity, an icon of independence and poise. As such, she has provided a connective thread between the six generations of girls she has ushered into adulthood." And Jain links Nancy's "smarts, pluck and independence" to the passions of the first Carolyn Keene, ghost-writer Mildred Wirt, "a young college graduate filled with the ideals of suffrage and the women’s movement."

As a class discussing The Mystery at Lilac Inn, we worked through the ways in which Nancy could be considered a valuable role model (and, Bonnie, you'll be pleased to know that one student did ask, "But isn't that a lot of pressure to put on the girls reading this?"), and we circled again around that word "progressive" in terms of the images and messages in the text. But at the same time, we couldn't help but be aware of the hints of conservatism lurking at the book's core—those parallel messages about upper-middle-class values, nostalgia for the past (look what's being done to the Lilac Inn!), about respectability and social grace and unerring etiquette.

We read the 1961 edition of the book, but I also brought in the original 1930 text—almost completely different. (In case readers here don't know, the original books were rewritten beginning in 1959, so for most of us, the Nancy Drew books we grew up on were not the original Nancy Drews.) In that 1930 version, not only are class issues more evident but—perhaps hand in hand—so are some unpalatable references to race and ethnicity. When Nancy is tasked with hiring a new housekeeper to temporarily replace Hannah Gruen (called away by a sister's illness), Nancy first interviews a "colored woman" ("dirty and slovenly in appearance and [with] an unpleasant way of shuffling her feet"), then the next morning an Irish woman ("even worse than the one that came yesterday") and a "Scotch lassie" ("she hadn't a particle of experience and knew little about cooking"). Later in that edition, the villains are revealed to be working class, uneducated, and mostly dark-complexioned; one is distinguished by a "hooked nose."

What's most interesting here isn't necessarily the racial/ethnic prejudices—signs of those times, one might argue—or the fact that these were revised away in the 1961 edition, there already in the midst of the Civil Rights Era (and the Cold War too, my students pointed out, noting that Nancy in 1961 also keeps criminals from selling secrets to enemy agents). Instead, what's possibly most interesting is that Wirt in 1994, in an introduction to a reprint of the original Mystery at Lilac Inn, stressed that "judging from reader letters, [Nancy] never was offensive" in the same paragraph where she talks—without explanation—about the books being rewritten beginning in the late 1950s.

...all of which brought us back to our earlier discussions of C.L. Pirkis and Baroness Orczy and Pauline Hopkins and to the assumptions underlying those discussions that the authors were intentionally or strategically challenging gender stereotypes. But were they always? And even where statements about gender issues seemed explicit—as with Lady Molly and the assertions about the Female Department's superiority—was the author aware of the negative attitudes toward lower classes crying out from elsewhere in the text? Were those latter messages explicitly intended as commentary on class, or was the author simply blind to how her views (and prejudices) had snuck into the writing?

In short, I guess, how can you tell when a writer is commenting on the values of her era—and when she's simply reflecting them?

And to flip this around, how many of us writing today are explicitly championing certain values in our work—and how many of us are unaware of the values we're revealing in those same works?

A good discussion in class on these topics—and I hope maybe a good discussion ahead here.