In 1963, folklorists took a closer look at the lyrics to an obscure 1928 Okeh recording called "Avalon Blues" and used them to track down long-forgotten guitarist Mississippi John Hurt, still alive and well in the town he described in the song. Hurt came out of retirement to become a headliner at folk festivals and coffee houses. His lyrical finger-picking became an inspiration for such upcoming musicians as John Sebastian, Happy Traum, Stefan Grossman and Chris Smither. All because of an old record.

We talk about clues in mysteries all the time, but other genres use them, too. They may call them "plot points" or "turning points" or something else, but a clue is simply something that moves the character closer to his goal: solving the mystery, finding true love, uncovering the cure for that lethal virus. OR it may send the character or the entire story off in a new direction.

Thanks to TV, we're attuned to discussing fingerprints, ballistics and blood spatter. We know about documentary evidence, too (Like the Hurt lyrics), and those are in our sights even more now because of the Mueller investigation. Both Conan Doyle ("The Adventure of the Dancing Men") and Edgar Allan Poe ("The Gold Bug") have stories that resolve because a character could decipher a coded message, and even the Hardy Boys carried on the tradition in The Mystery of Cabin Island.

Sometimes, though, a clue is less concrete, which gives us a chance to play a little and maybe sneak one past our readers. My favorite NON-clue is in the Sherlock Holmes story "Silver Blaze," which Holmes solved by paying attention to the dog that did NOT bark. A similar idea shows up in my current WIP.

Stephen King turns forensic evidence on its head in The Outsider, his recent novel which Rob discussed a few days ago. We have a man accused of murdering a child, and the DNA samples are undoubtedly his. That's fairly standard. But witness and photographs place him hundreds of miles away when the crime was committed. When the forensics and documentary evidence collide, the cops find themselves in Plan B and the book shifts from a typical police procedural into King's more familiar domain, the Twilight Zone. He does the what's-wrong-with-this-picture stuff as well as anyone else in the business.

Anyone here old enough to remember the TV show Hong Kong? It only ran for one season, starting in September 1960. Rod Taylor played a journalist, and in one episode, he narrowly escaped being run down by a taxi. Soon after that, a man he was talking to was shot. Everyone believed Taylor was the real target and the shooter had bad aim, but later in the show, Taylor tracked down the taxi driver, who told him that he had been paid to MISS Taylor with his cab. That showed that the dead man was the intended victim after all and the fake attempt on Taylor was to conceal the real motive.

My own Blood on the Tracks has Woody Guthrie trying to find a stolen tape of a forgotten rock band, and nobody can understand why anyone cares about the tape. Eventually, Guthrie learns that something may have been recorded OVER some of the tape and that the bad guys are after something besides the musical performance. Which means a different set of people might want it...

In Jane Austen's Pride and Prejudice, Lizzie spends most of the book thinking Mr. Darcy is an insufferable snot and dislikes him for how he has treated her older sister Jane. Eventually, she discovers that he is trying to help her younger sister Lydia, who has run off with a wastrel and is in danger of ruining her own reputation (not to mention her life) and that of her entire family. When Lizzie finds that Darcy is buying the blackguard off, it makes her see him more clearly...and paves the way to their own happy ending.

Some of my favorite plot reversals (call them clues, too) appear in science fiction. Damon Knight's "To Serve Man" offers a manuscript from another planet that those beings give to earthlings as a sign of good faith. It's also a clue. When someone translates the entire text, they discover it's a cookbook and the double meaning of the word "serve" becomes important. The story became an episode of The Twilight Zone in 1962, and many people cite it as one of their favorites.

Pierre Boulle's novel became the basis for the first Planet of the Apes film, and who can forget that closing shot of Charleton Heston looking at the mostly buried Statue of Liberty and understanding for the first time that he's not on a distant planet? The primates have become the dominant species on earth after a nuclear war destroyed civilization. Oops.

How about you? How do you give your readers the clue that moves the story off the tracks?

Showing posts with label plot twists. Show all posts

Showing posts with label plot twists. Show all posts

20 August 2018

Blues and Clues

by Steve Liskow

Labels:

Arthur Conan Doyle,

clues,

Edgar Allan Poe,

Jane Austen,

music,

plot twists,

Stephen King,

Steve Liskow

Location:

Newington, CT, USA

19 June 2017

Hiding the Ball

by Steve Liskow

by Steve Liskow

If you read or write police procedurals, you probably know far too much about fingerprint patterns, blood spatter,

decay rates, DNA matching, ballistics and digital technology. Modern law enforcement relies on forensic evidence to solve crimes, and it works, which is all to our benefit. But it reduces the human (read, "character") factor in modern stories. I can't avoid them altogether, but I try to rely on them as little as possible.

Why, you ask. OK, I'm not a Luddite (although I do write my early notes with a fountain pen) but...

Readers want to participate in your mystery. The stories from the Golden Age--back before you and I were even born--required that the sleuth share his or her discoveries with the reader so we could figure out the solution (or, more typically, NOT) along with him. That's why so many of the classic stories of Agatha Christie, Nero Wolf and their peers had a sidekick as the narrator so he didn't have to give the sleuth's thoughts away. It also explains why those stories are so convoluted and complicated. The writers did what attorneys now call "hiding the ball," burying the real clues in mountains of red herrings, lying witnesses, contradictory information and complicated maps, not necessarily drawn to scale.

The Ellery Queen series featured the "Challenge to the Reader" near the end of the book, stating that at that point the reader had ALL the necessary information to arrive at the "One Logical Solution." It was a daunting challenge that I think I met only once or twice. Agatha Christie said she did her plotting while doing household chores. I'd like to see the banquets she prepared to come up with some of Poirot's herculean feats.

If you withhold the clues and pull them out at the end like a rabbit out of a top hat, readers accuse you of cheating. I still remember an Ellery Queen novel that solved the murder of a twin brother by revealing at the end that there were actually triplets. Tacky, tacky, tacky.

You need to put the information out there where readers can see it, but without making it too obvious.

Magicians accompany their sleight of hand with distractions: stage patter, light and smoke and mirrors, scantily clad assistants, and anything else that will make you look that way instead of at them while they palm the card or switch the glasses. And that's how you do it in mysteries, too.

There are a few standard tricks we all use over and over because they work.

The first is the "hiding the ball" trick I mentioned above. If you describe a parking lot with twelve red Toyotas, nobody will notice one with a dented fender or an out-of-state license plate. The B side of this is establishing a pattern, then breaking it. Often, the sleuth believes that oddball is a different culprit and not part of the same case, but he finally figures out that it's the only one that matters and the others were decoys.

You can also give people information in what retailers used to call a "bait and switch." Stores would advertise an item at a low price, then tell customers that item was already sold out and try to sell them a more expensive version. You can give readers information about a person or event, then tweak it later so it points somewhere else. The classic police procedural The Laughing Policeman hinges on a witness identifying an automobile parked at a scene...then years later realizing that a different car looks a lot like it. Oops.

You can give information and later show that the witness who mentioned it was lying. The trick here is to plant a reason for the witness to lie early in the story and leave the connection until later on. If the reader sees the reason with no context, he'll overlook it until you make it important again when you pull the bunny out of the derby. This is one of my favorites.

I also like to focus on a fact or circumstance that's irrelevant and keep coming back to it. Later in the story, your detective can figure out that it's meaningless...OR realize that he's look at it from the wrong angle. My recent story "Look What They've Done to My Song, Ma" has PI Woody Guthrie and his musician companion Megan Traine trying to clean up a music file so they can identify the voice that's talking underneath the singer. It's not until late in the story that Guthrie realizes the voice doesn't matter--at least, not the way he thought it did, because the speaker isn't the person everyone assumed it was. That story appears in the July/August issue of Alfred Hitchcock's Mystery Magazine, along with stories by known accomplices John Floyd and O'Neil De Noux.

The "how could he know that?" clue gets lots of use, too. Someone makes a comment, suggestion, or observation and the sleuth doesn't realize until later that he couldn't have known the murder weapon or condition of the body unless he was there. If you haven't used this one at least once, raise your hand.

Its second cousin is the condition or event that didn't happen, the old case of the dog that didn't bark in the night, first used in "Silver Blaze," an early Sherlock Holmes story. Its fraternal twin, which makes a handy red herring in the age of technology, is a missing computer file. Since it's missing, we don't know what's on it...or if it's even important. The sleuth can spend pages or even entire chapters worrying about that missing file folder or computer. In The Kids Are All Right, I had two murder victims whose computers were found with the respective hard drives removed. The implication was that missing files would implicate the killer. But can we really be sure?

Now, what's your favorite way to deal off the bottom?

If you read or write police procedurals, you probably know far too much about fingerprint patterns, blood spatter,

decay rates, DNA matching, ballistics and digital technology. Modern law enforcement relies on forensic evidence to solve crimes, and it works, which is all to our benefit. But it reduces the human (read, "character") factor in modern stories. I can't avoid them altogether, but I try to rely on them as little as possible.

Why, you ask. OK, I'm not a Luddite (although I do write my early notes with a fountain pen) but...

Readers want to participate in your mystery. The stories from the Golden Age--back before you and I were even born--required that the sleuth share his or her discoveries with the reader so we could figure out the solution (or, more typically, NOT) along with him. That's why so many of the classic stories of Agatha Christie, Nero Wolf and their peers had a sidekick as the narrator so he didn't have to give the sleuth's thoughts away. It also explains why those stories are so convoluted and complicated. The writers did what attorneys now call "hiding the ball," burying the real clues in mountains of red herrings, lying witnesses, contradictory information and complicated maps, not necessarily drawn to scale.

The Ellery Queen series featured the "Challenge to the Reader" near the end of the book, stating that at that point the reader had ALL the necessary information to arrive at the "One Logical Solution." It was a daunting challenge that I think I met only once or twice. Agatha Christie said she did her plotting while doing household chores. I'd like to see the banquets she prepared to come up with some of Poirot's herculean feats.

If you withhold the clues and pull them out at the end like a rabbit out of a top hat, readers accuse you of cheating. I still remember an Ellery Queen novel that solved the murder of a twin brother by revealing at the end that there were actually triplets. Tacky, tacky, tacky.

You need to put the information out there where readers can see it, but without making it too obvious.

Magicians accompany their sleight of hand with distractions: stage patter, light and smoke and mirrors, scantily clad assistants, and anything else that will make you look that way instead of at them while they palm the card or switch the glasses. And that's how you do it in mysteries, too.

There are a few standard tricks we all use over and over because they work.

The first is the "hiding the ball" trick I mentioned above. If you describe a parking lot with twelve red Toyotas, nobody will notice one with a dented fender or an out-of-state license plate. The B side of this is establishing a pattern, then breaking it. Often, the sleuth believes that oddball is a different culprit and not part of the same case, but he finally figures out that it's the only one that matters and the others were decoys.

You can also give people information in what retailers used to call a "bait and switch." Stores would advertise an item at a low price, then tell customers that item was already sold out and try to sell them a more expensive version. You can give readers information about a person or event, then tweak it later so it points somewhere else. The classic police procedural The Laughing Policeman hinges on a witness identifying an automobile parked at a scene...then years later realizing that a different car looks a lot like it. Oops.

You can give information and later show that the witness who mentioned it was lying. The trick here is to plant a reason for the witness to lie early in the story and leave the connection until later on. If the reader sees the reason with no context, he'll overlook it until you make it important again when you pull the bunny out of the derby. This is one of my favorites.

I also like to focus on a fact or circumstance that's irrelevant and keep coming back to it. Later in the story, your detective can figure out that it's meaningless...OR realize that he's look at it from the wrong angle. My recent story "Look What They've Done to My Song, Ma" has PI Woody Guthrie and his musician companion Megan Traine trying to clean up a music file so they can identify the voice that's talking underneath the singer. It's not until late in the story that Guthrie realizes the voice doesn't matter--at least, not the way he thought it did, because the speaker isn't the person everyone assumed it was. That story appears in the July/August issue of Alfred Hitchcock's Mystery Magazine, along with stories by known accomplices John Floyd and O'Neil De Noux.

The "how could he know that?" clue gets lots of use, too. Someone makes a comment, suggestion, or observation and the sleuth doesn't realize until later that he couldn't have known the murder weapon or condition of the body unless he was there. If you haven't used this one at least once, raise your hand.

Its second cousin is the condition or event that didn't happen, the old case of the dog that didn't bark in the night, first used in "Silver Blaze," an early Sherlock Holmes story. Its fraternal twin, which makes a handy red herring in the age of technology, is a missing computer file. Since it's missing, we don't know what's on it...or if it's even important. The sleuth can spend pages or even entire chapters worrying about that missing file folder or computer. In The Kids Are All Right, I had two murder victims whose computers were found with the respective hard drives removed. The implication was that missing files would implicate the killer. But can we really be sure?

Now, what's your favorite way to deal off the bottom?

Labels:

clues,

playing fair,

plot twists,

red herring,

Steve Liskow

Location:

Newington, CT, USA

03 April 2017

Hail! Hail! Rock 'n' Roll

by Steve Liskow

On March 18, Chuck Berry passed away at the tender age of 90 years and 5 months. All the media featured glowing eulogies and long articles about his influence on rock and pop music and how his guitar style became the fountainhead of rock, paving the way for everyone from George Harrison and Keith Richards to Jack White and Ted Nugent and a million unknowns like me.

It's true that Berry popularized licks that Robert Johnson and Elmore James had made blues cliches. What's easier to overlook is that Berry was a terrific lyricist who turned two-and-a-half-minute pop songs into short stories that resonated with his young audience. He gave teens in the Fifties a voice with dozens of songs that became rock standards, and he showed a whole generation of songwriters who followed him how to do it.

F. Scott Fitzgerald once told his daughter that to learn to write English prose, one should compose a perfect English sonnet. He said the form is so rigid that the writer has to learn to work within the constraints. Berry did him even better, working within the boundaries of a simplified music form that demanded he also match the rhythm and melody to the mood and meaning.

Berry was nearly 30 when he recorded "Mabellene," his first hit, backed by members of the Muddy Waters blues band. That song borrowed from a country song called "Ida Red," but Berry added a guitar lick that imitated a car horn. He also added a plot involving cars and speed and unrequited love. The Beach Boys would ride this formula into the ground a few years later, with Carl Wilson imitating Berry's guitar on "Fun, Fun, Fun," "409," "Dance, Dance, Dance," and several other songs.

Berry knew about isolation and angst, too. Don't forget, he was a black kid growing up in St. Louis when segregation was still the norm. He knew about not having it all, and he understood the pressures to survive. "Almost Grown" tells us about small victories and small dreams, all he dares to have:

"I don't run around with no mob/ I got myself a little job./ I'm gonna buy myself a little car/

I'll drive my girl in the park."

"School Day" captures the feel of being stuck in a big urban school where he's just a name in a grade book, if he's even that. Millions of kids knew what he meant when he said:

"American Hist'ry and Practical Math, You study 'em hard and hopin' to pass.

Workin' your fingers right down to the bone, And the guy behind you won't leave you alone."

He's added conflict to the mix, as all good story-tellers do. And the savior is rock 'n' roll:

"Soon as three o'clock rolls around, you finally lay your burden down...

Drop the coin right into the slot, you gotta hear somethin' that's really hot."

And there's our resolution, finishing with the line "Hail! Hail! Rock 'n' roll!"

"No Money Down," one of his lesser hits, tells of a fast-talking used car salesman who offers outrageous deals to get our hero into a flashy new car and out of "that broken-down raggedy ol' Ford."

Berry constantly uses contrasts to make his point. Sometimes it's verbal, but sometimes he sets happy music against a serious story. "Memphis, Tennessee," covered by Lonnie Mack as an instrumental that lost the irony, and later by Johnny Rivers, tells the understated story of a broken marriage as a father tries to reach the little girl he no longer gets to see:

"Help me, Information, bet in touch with my Marie,

She's the only one who'd phone me here from Memphis, Tennessee

...We were pulled apart because her mom did not agree

And tore apart our happy home in Memphis, Tennessee

...Marie is only six years old, Information, please,

Try to put me through to her in Memphis, Tennessee."

That song is from 1959, when most acts were still singing about sunshine, lollipops, and rainbows. Berry is addressing more serious topics.

Humor helps him balance the hopes and reams that crash into the reality of color and youth. But things will change. When we learn more, the dreams get bigger. Berry's signature song was "Johnny B. Goode," about a little country boy ("Colored" originally, but he changed it to get radio air play) who

"...never ever learned to read or write so well, but he could play a guitar just like a-ringin' a bell."

This song has the archetypal Chuck Berry riff and the variations show up in song after song. If you were a kid of the time--like the Beatles, the Stones, the Yardbirds, the Beach Boys, the MC5, Ted Nugent, Jerry Garcia, or thousands of other Baby Boomers like me--these were the licks you HAD to have in your arsenal, along with "Louie Louie," "Gloria," and--if you had a drummer with moxie--"Wipeout." Not just because the girls went crazy if you could duck walk to them, but because they kicked ass like nobody had ever done before.

The song shows where that little country boy can go, too.

"Maybe someday you name'll be in lights a-sayin' 'Johnny B. Goode tonight!'"

Dream big, dream bigger. Go, Johnny, Go.

Berry's other lyrical gift is humor. Teen-age frustration creates dramatic tension and comic outcomes, often at his own expense. He captures youthful angst with humor and economy, again in rhyme and simple rhythms. "No Particular Place to Go,' which has almost the same melody as "School Day," tells of a kid who has a car (Maybe even that broken-down raggedy ol' Ford) and a girl..and hopes to parlay the combination into some action. But it doesn't happen:

"The night was young and the moon was gold, so we both decided to take a stroll

Can you imagine the way I felt, I couldn't unfasten her safety belt.

Riding along in my calaboose, still trying to get her belt unloose

All the way home I held a grudge for the safety belt that wouldn't budge..."

Simple? Sure. But simple is hard because you can't hide anything.

Years later, I met Joe Bouchard, the former bass player from Blue Oyster Cult, when I took a theater design class along with his wife. When the instructor mentioned that BOC was the first band to use lasers and flash pots in their stage act, Bouchard almost blushed.

"Yeah," he finally said. "The monitors back then sucked, so we couldn't always tell, but the bells and whistles keep people from noticing that sometimes we weren't in tune."

Maybe Berry's guitar wasn't always in tune, but his stories never missed.

Rock on, Chuck.

It's true that Berry popularized licks that Robert Johnson and Elmore James had made blues cliches. What's easier to overlook is that Berry was a terrific lyricist who turned two-and-a-half-minute pop songs into short stories that resonated with his young audience. He gave teens in the Fifties a voice with dozens of songs that became rock standards, and he showed a whole generation of songwriters who followed him how to do it.

F. Scott Fitzgerald once told his daughter that to learn to write English prose, one should compose a perfect English sonnet. He said the form is so rigid that the writer has to learn to work within the constraints. Berry did him even better, working within the boundaries of a simplified music form that demanded he also match the rhythm and melody to the mood and meaning.

Berry was nearly 30 when he recorded "Mabellene," his first hit, backed by members of the Muddy Waters blues band. That song borrowed from a country song called "Ida Red," but Berry added a guitar lick that imitated a car horn. He also added a plot involving cars and speed and unrequited love. The Beach Boys would ride this formula into the ground a few years later, with Carl Wilson imitating Berry's guitar on "Fun, Fun, Fun," "409," "Dance, Dance, Dance," and several other songs.

Berry knew about isolation and angst, too. Don't forget, he was a black kid growing up in St. Louis when segregation was still the norm. He knew about not having it all, and he understood the pressures to survive. "Almost Grown" tells us about small victories and small dreams, all he dares to have:

"I don't run around with no mob/ I got myself a little job./ I'm gonna buy myself a little car/

I'll drive my girl in the park."

"School Day" captures the feel of being stuck in a big urban school where he's just a name in a grade book, if he's even that. Millions of kids knew what he meant when he said:

"American Hist'ry and Practical Math, You study 'em hard and hopin' to pass.

Workin' your fingers right down to the bone, And the guy behind you won't leave you alone."

He's added conflict to the mix, as all good story-tellers do. And the savior is rock 'n' roll:

"Soon as three o'clock rolls around, you finally lay your burden down...

Drop the coin right into the slot, you gotta hear somethin' that's really hot."

And there's our resolution, finishing with the line "Hail! Hail! Rock 'n' roll!"

"No Money Down," one of his lesser hits, tells of a fast-talking used car salesman who offers outrageous deals to get our hero into a flashy new car and out of "that broken-down raggedy ol' Ford."

Berry constantly uses contrasts to make his point. Sometimes it's verbal, but sometimes he sets happy music against a serious story. "Memphis, Tennessee," covered by Lonnie Mack as an instrumental that lost the irony, and later by Johnny Rivers, tells the understated story of a broken marriage as a father tries to reach the little girl he no longer gets to see:

"Help me, Information, bet in touch with my Marie,

She's the only one who'd phone me here from Memphis, Tennessee

...We were pulled apart because her mom did not agree

And tore apart our happy home in Memphis, Tennessee

...Marie is only six years old, Information, please,

Try to put me through to her in Memphis, Tennessee."

That song is from 1959, when most acts were still singing about sunshine, lollipops, and rainbows. Berry is addressing more serious topics.

Humor helps him balance the hopes and reams that crash into the reality of color and youth. But things will change. When we learn more, the dreams get bigger. Berry's signature song was "Johnny B. Goode," about a little country boy ("Colored" originally, but he changed it to get radio air play) who

"...never ever learned to read or write so well, but he could play a guitar just like a-ringin' a bell."

This song has the archetypal Chuck Berry riff and the variations show up in song after song. If you were a kid of the time--like the Beatles, the Stones, the Yardbirds, the Beach Boys, the MC5, Ted Nugent, Jerry Garcia, or thousands of other Baby Boomers like me--these were the licks you HAD to have in your arsenal, along with "Louie Louie," "Gloria," and--if you had a drummer with moxie--"Wipeout." Not just because the girls went crazy if you could duck walk to them, but because they kicked ass like nobody had ever done before.

The song shows where that little country boy can go, too.

"Maybe someday you name'll be in lights a-sayin' 'Johnny B. Goode tonight!'"

Dream big, dream bigger. Go, Johnny, Go.

Berry's other lyrical gift is humor. Teen-age frustration creates dramatic tension and comic outcomes, often at his own expense. He captures youthful angst with humor and economy, again in rhyme and simple rhythms. "No Particular Place to Go,' which has almost the same melody as "School Day," tells of a kid who has a car (Maybe even that broken-down raggedy ol' Ford) and a girl..and hopes to parlay the combination into some action. But it doesn't happen:

"The night was young and the moon was gold, so we both decided to take a stroll

Can you imagine the way I felt, I couldn't unfasten her safety belt.

Riding along in my calaboose, still trying to get her belt unloose

All the way home I held a grudge for the safety belt that wouldn't budge..."

Simple? Sure. But simple is hard because you can't hide anything.

Years later, I met Joe Bouchard, the former bass player from Blue Oyster Cult, when I took a theater design class along with his wife. When the instructor mentioned that BOC was the first band to use lasers and flash pots in their stage act, Bouchard almost blushed.

"Yeah," he finally said. "The monitors back then sucked, so we couldn't always tell, but the bells and whistles keep people from noticing that sometimes we weren't in tune."

Maybe Berry's guitar wasn't always in tune, but his stories never missed.

Rock on, Chuck.

Labels:

music,

plot twists,

Steve Liskow

Location:

Newington, CT, USA

04 March 2017

Let's Do the Twist

by John Floyd

by John M. Floyd

In his book Spunk & Bite, author and publisher Arthur Plotnik says, "Readers love surprise. They love it when a sentence heads one way and jerks another."

In his book Spunk & Bite, author and publisher Arthur Plotnik says, "Readers love surprise. They love it when a sentence heads one way and jerks another."How true. And what works in language/style also seems to work--at least in this case--in plots. Readers, and viewers too, like it when the story takes a sudden and unforeseen turn. Sometimes it's just a side street that eventually leads us back to the freeway, but occasionally it's a major roadblock that sends us off in a totally different direction, or even headed back the way we came.

Off-balancing act

FYI, I'm not talking specifically about surprise endings, like those in Shutter Island, Primal Fear, The Sixth Sense, Fight Club, Planet of the Apes, Presumed Innocent, The Usual Suspects, "The Lottery," "The Gift of the Magi," etc. The reversals I'm talking about can also occur earlier in the story.

Nobody who reads fiction (or watches movies) wants the characters to have an easy, carefree ride. We want our hero or heroine to be challenged, and not only with that initial "call to adventure." We want him or her weighted down with burdens and decisions and constantly-changing threats. And the main thing, here, is changing. Since we as human beings are always worried about changes in our own lives, we as readers are worried when characters face changes--illness, death, divorce, a new job, loss of a job, a new location, strangers who come to town, and so forth--and have to deal with them. It adds to the "uncertainty of outcome" that's such an integral piece of storytelling. This happens in all good stories, but a part of that, especially in genre fiction, is injecting twists and turns throughout the tale.

Shock treatment

I always enjoy movies and novels that contain those in-flight reversals. There are many examples, but the following stories--all of them are films and most were books as well--come to mind because they feature a sudden 180-degree switcheroo in or near Act II: A Kiss Before Dying, Psycho, L.A. Confidential, Executive Decision, Ransom, Gone Girl, Deep Blue Sea, Marathon Man, etc. And I don't mean a slight swerve off the path; I mean a clap-your-hands-over-your-mouth and bug-out-your-eyes stunner that completely changes the course of the story.

The reversals in the movie versions of Psycho and L.A. Confidential were especially memorable because--in each case--the best-known actor in the cast was unexpectedly killed in the middle of the story (early middle in Psycho, late middle in LAC). That also happened when the most famous actor in Game of Thrones bit the dust (well, his severed head did) in the final episode of the very first season. It left viewers thunderstruck, and understandably wondering what other off-the-charts events might happen, and when. If long-term tension is what you're trying to create (as a writer/director) and what you enjoy (as a reader/viewer), this is a pretty effective plot device.

It occurred to me, while I was writing this, that one definition of the word reversal is "a setback, or a change of fortune for the worse"--as in, I suppose, a deep dip in the Dow Jones--and I think that definition holds true for today's topic as well. Reversals in fiction are often for the worse, and that can help the story. More conflict, and more agony for the protagonist, means more suspense.

A sense of misdirection

Other tales that had big mid-story twists: The Maze Runner, Reservoir Dogs, The Departed, "A Good Man Is Hard to Find," Life of Pi, Sands of the Kalahari, A History of Violence, The Hateful 8, Blood Simple--and almost any short story by Roald Dahl and any novel by Harlan Coben. Those two authors were/are masters of the plot reversal.

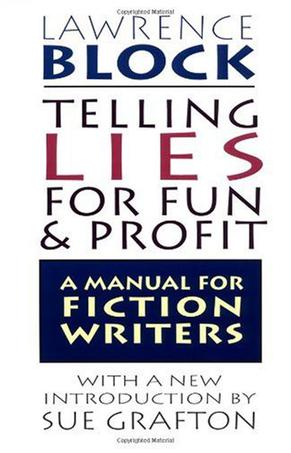

With regard to endings, Lawrence Block had an interesting observation about that in his book Telling Lies for Fun and Profit. He said, "The best surprise endings don't merely surprise the reader. In addition, they force him to reevaluate everything that has preceded them, so that he views the actions and the characters in a different light and has a new perspective on all that he's read."

With regard to endings, Lawrence Block had an interesting observation about that in his book Telling Lies for Fun and Profit. He said, "The best surprise endings don't merely surprise the reader. In addition, they force him to reevaluate everything that has preceded them, so that he views the actions and the characters in a different light and has a new perspective on all that he's read."At the risk of repeating myself, I think the same thing applies to twists and reversals during the course of the narrative. If you're good enough, you can use reversals to keep a reader off-balance and still maintain the central storyline. The diversions, when included, should be there for a reason, and not just for shock value and entertainment. The twists should fit in and be logical, and should--ideally--make the journey more interesting to the traveler.

Questions

Do you agree? Is that something you try to do in your own writing, or look for in your reading and/or viewing? What are some of your favorite reversals in movies, novels, and stories? Can you think of some that didn't work well? Which ones surprised you the most? I think I actually spilled Coke on the people around me in the theater when Janet Leigh met her fate in the Bates Motel (that bombshell seemed to drop almost as soon as I got settled into my seat), and I choked on my popcorn when the guy pushed his date off the roof of the building in the first half of A Kiss Before Dying. I'll remember those scenes always. And that's more than I can say for a lot of the novels I've read and the movies I've seen lately.

In real life, certainty and security are comforting. In fiction, the future is always unpredictable.

Or should be.

06 August 2012

Surprise Endings

by Fran Rizer

O. Henry was one of my favorite writers when I was a child. I loved the surprise endings in each of his tales. Almost everyone is familiar with some of his short stories, especially "Gift of the Magi" and "Ransom of Red Chief." My favorite was "Mammon and the Archer."

Periodically, I survey my universe and eradicate the negatives, which has frequently led to breakups with gentlemen friends. This tends to correspond with "cleaning out my library" which results in my giving away books which I later wish I'd kept. Inevitably, I've changed my mind and wanted those stories back, (though not the gentlemen friends), so I've bought numerous copies of the Complete Works of O. Henry through the years. I enjoy his work now as much as I ever did.

William Sydney Porter was born in Asheville, North Carolina, but began receiving recognition for his writing under the pseudonym Olivier Henry while living in Texas, where he was convicted of embezzlement and spent time in prison. Upon his release, he moved to New York City and began writing under the pen name O. Henry

Since his death at age forty-seven, O. Henry has had several supporters offer evidence that he was innocent of the embezzlement. There is an O. Henry Museum in his honor in Texas.

Regardless of his youthful guilt or innocence, O. Henry remains one of my favorite writers and an inspiration for the unexpected ending. Needless to say, he immediately came to mind when I discovered PARAPROSDOKIANS.

PARAPROSDOKIANS are figures of speech in which the latter part of a sentence or phrase is surprising or unexpected and frequently humorous. Sir Winston Churchill loved them, and I'll bet O. Henry would have, too.

Some examples:

1. Where there's a will, I want to be in it.

2. The last thing I want to do is hurt you, but it's still on my list.

3. Since light travels faster than sound, some people appear bright until you hear them speak.

4. If I agreed with you, we'd both be wrong.

5. War does not determine who is right--only who is left.

6. To steal ideas from one person is plagiarism; to steal from many is research.

7. I thought I wanted a career, turns out I just wanted paychecks.

8. I asked God for a bike, but I know God doesn't work that way, so I stole a bike and prayed for forgiveness.

9. I didn't say it was your fault; I said I was blaming you.

10. Women will never be equal to men until they can walk down the street with a bald head and a beer gut and still think they are sexy.

11. A clear conscience is a sign of a fuzzy memory.

12. You don't need a parachute to skydive; you only need a parachute to skydive twice.

13. I used to be indecisive; now I'm not so sure.

14. To be sure of hitting the target, shoot first and call whatever you hit the target.

15. Nostalgia isn't what it used to be.

16. Change is inevitable, except from a vending machine.

17. Going to church doesn't make you a Christian any more than standing in a garage makes you a car.

18. I am neither for nor against apathy.

19. Some cause happiness wherever they go; others, whenever they go.

20. Knowledge is knowing a tomato is a fruit; wisdom is not putting it into a fruit salad.

How about you? Do you have a favorite of the twenty PARAPROSDOKIANS above or perhaps one not listed? Better yet, make one up and share it!

Until we meet again. . . take care of YOU!

Periodically, I survey my universe and eradicate the negatives, which has frequently led to breakups with gentlemen friends. This tends to correspond with "cleaning out my library" which results in my giving away books which I later wish I'd kept. Inevitably, I've changed my mind and wanted those stories back, (though not the gentlemen friends), so I've bought numerous copies of the Complete Works of O. Henry through the years. I enjoy his work now as much as I ever did.

|

| William Sydney Porter aka O. Henry aka Olivier Henry |

Since his death at age forty-seven, O. Henry has had several supporters offer evidence that he was innocent of the embezzlement. There is an O. Henry Museum in his honor in Texas.

Regardless of his youthful guilt or innocence, O. Henry remains one of my favorite writers and an inspiration for the unexpected ending. Needless to say, he immediately came to mind when I discovered PARAPROSDOKIANS.

|

| Sir Winston Churchill |

Some examples:

1. Where there's a will, I want to be in it.

2. The last thing I want to do is hurt you, but it's still on my list.

3. Since light travels faster than sound, some people appear bright until you hear them speak.

4. If I agreed with you, we'd both be wrong.

5. War does not determine who is right--only who is left.

6. To steal ideas from one person is plagiarism; to steal from many is research.

7. I thought I wanted a career, turns out I just wanted paychecks.

8. I asked God for a bike, but I know God doesn't work that way, so I stole a bike and prayed for forgiveness.

9. I didn't say it was your fault; I said I was blaming you.

|

| "I'm sexy and I know it!" |

11. A clear conscience is a sign of a fuzzy memory.

12. You don't need a parachute to skydive; you only need a parachute to skydive twice.

13. I used to be indecisive; now I'm not so sure.

14. To be sure of hitting the target, shoot first and call whatever you hit the target.

15. Nostalgia isn't what it used to be.

16. Change is inevitable, except from a vending machine.

17. Going to church doesn't make you a Christian any more than standing in a garage makes you a car.

18. I am neither for nor against apathy.

19. Some cause happiness wherever they go; others, whenever they go.

20. Knowledge is knowing a tomato is a fruit; wisdom is not putting it into a fruit salad.

How about you? Do you have a favorite of the twenty PARAPROSDOKIANS above or perhaps one not listed? Better yet, make one up and share it!

Until we meet again. . . take care of YOU!

Labels:

Fran Rizer,

O. Henry,

paraprosdokians,

plot twists

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)