When you say folk music in America, the first thing that comes to most people's mind is Peter, Paul, and Mary, Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, and music that's a mixture of politics and sweet ballads. Folk music in Britain? Try some of the dark stuff. You want to know how to cheat the Fairy Queen? Kill a monster or two? Go crazy? Be killed by a werefox? Try old British folk songs.

When you say folk music in America, the first thing that comes to most people's mind is Peter, Paul, and Mary, Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, and music that's a mixture of politics and sweet ballads. Folk music in Britain? Try some of the dark stuff. You want to know how to cheat the Fairy Queen? Kill a monster or two? Go crazy? Be killed by a werefox? Try old British folk songs.Back in 1969, a British group called Fairport Convention issued their fourth album, called "Liege and Lief". It's been credited as the beginning of the "British folk rock" movement, and in 2006 it was voted "Most Influential Folk Album of All Time". I love this album, because it's chock full of traditional British and Celtic folk material, done with an edge and a steel guitar. And the amazing vocals of Sandy Denny. Let's just say it makes for a good, alternative Halloween sound track.

My personal favorite on Liege & Lief is Reynardine. Listen to it here:

"Your beauty so enticed me

I could not pass it by

So it's with my gun I'll guard you

All on the mountains high."

"And if by chance you should look for me

Perhaps you'll not me find

For I'll be in my castle

Inquire for Reynardine."

Sun and dark, she followed him

His teeth did brightly shine

And he led her above mountains

Did that sly old Reynardine

And, to prove that fairy tales can come true, they can happen to you, try this (fairly obscure) movie by Neil Jordan, "In the Company of Wolves", starring Angela Lansbury as Granny, who tells her granddaughter Rosaleen stories about werewolves, wolves, innocent girls, dangerous strangers, and full moons... (See the trailer below:)

Back to Fairport Convention and the eerie "Crazy Man Michael":

Pair that with Francis Ford Coppola's "Dementia 13", set in an Irish castle, and you'll probably check under the bed at night. And lock all the doors. Maybe burn a little sage...

Of course, sometimes they aren't crazy. In "Grabbers", directed by Jon Wright, a small rural Irish village is taken over by monstrous sea creatures who love the typical Irish day: constant rain and drizzle. The creatures are killing off as many people as they possibly can, as gruesomely as possible. But they have one weakness – alcohol. If you're drunk, they can't kill you. So, the whole village takes to steady drinking... Laughs, gore, and terror, what more can you ask for?

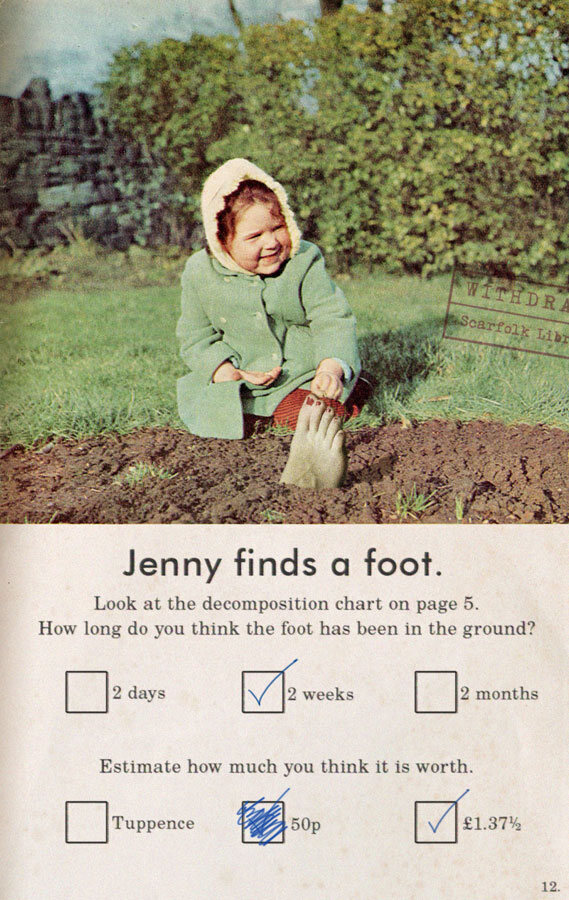

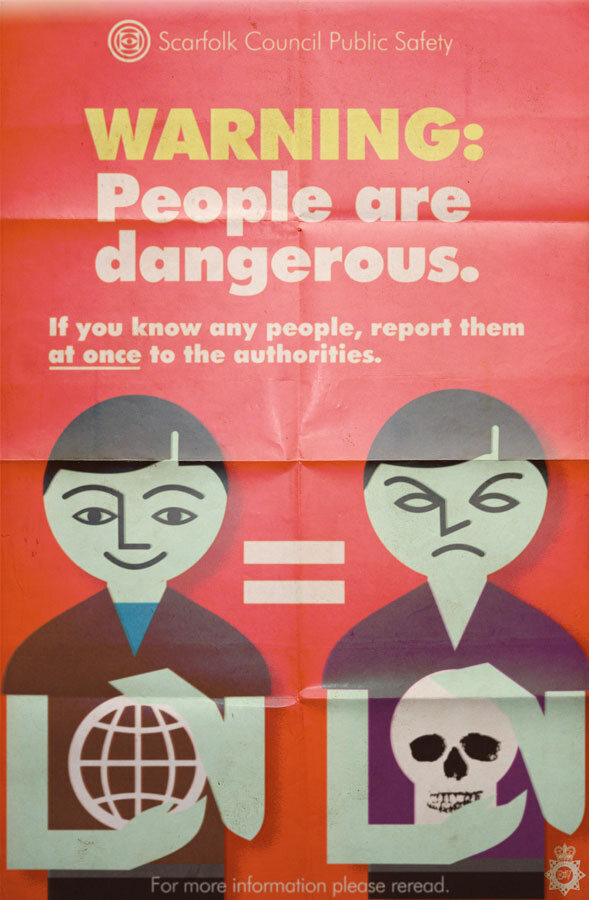

BTW, all the photos above are from "Scarfolk, England's creepiest fake town,". A big shout out to AtlasObscura.com for a great article. Check out, also:

Carmilla, the first vampire story by Sheridan LeFanu

The Essential Guide to Living Lovecraft

Traveling Thru Transylvania with Dracula

Satan's Subliminal Rock Music Messages

Finally, two things: first of all from Pink Floyd, a wonderful song that is, perhaps, the Addams Family lullaby, "Careful with that Axe, Eugene":

And for a last video, check out Michael Mann's 1983 movie, "The Keep". It is World War II in German-occupied Romania. Nazi soldiers have been sent to garrison a mysterious fortress, but a nightmarish discovery is soon made. The Keep was not built to keep anything out. The massive structure was, in fact built to keep something in...

Happy Halloween!