|

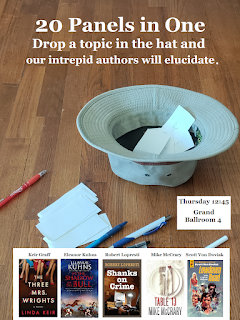

| LCC 2022. Courtesy of Kelly Garrett |

Back in the spring I attended Left Coast Crime in Albuquerque. I have already blogged about that twice but I rediscovered another topic in my notes I wanted to write about.

PLANNING AHEAD

1. Getting to know you. As soon as you know who will be on the panel, talk to them. Do you all agree on the topic? Sometimes the titles chosen by The Powers That Be are ambiguous, or can be misunderstood. (Famous story from the world of folk music: One festival asked Arlo Guthrie to be on a Tropical Songs workshop so he learned "Ukulele Lady." Turned out the topic was TOPICAL Songs... But he later recorded the song, so it wasn't a waste.

2. Read ahead, Read some of the works of each of your panelists. That will lead to better questions, make it look like you know what you are talking about, and please the panelists.

3. Prepare your questions early. Procrastination is not your friend her

4. Abundance mindset. Prepare more questions than you think you will need.

|

| Bouchercon 2014 |

5. Share the questions with your panelists. I know there are those who disagree with me on this and, as usual when people disagree with me, they are wrong. A conference panel is not a quiz show with points for spontaneity. Nor is it a final exam where knowing the questions in advance is cheating. You have two goals: to entertain/inform the audience, and to make the panelists look good. Neither goal is advanced by causing your team to waste precious seconds fumbling for an intelligent answer. There will be plenty of opportunity for them to improvise anyway.

6. Two-way street. Telling them in advance also gives you a chance to invite them to suggest questions. Maybe they know something about the topic you don't. In fact, let's hope they do!

7. No surprises. I once served on a panel whose moderator decided each of us should read an excerpt from our book. Nothing wrong with that except the moderator didn't tell us that until we were in the green room half an hour before the panel started. That meant all of us who should be relaxing and getting to know each other were instead fumbling through their books searching for the perfect passage. Time to practice your recitation? Dream on.

8. Get it right. Make sure you know how to pronounce the names of the panelists (and characters and book titles, if appropriate). At LCC I was careful to check a tricky pronunciation but blew one that looked obvious.

9. Poster boys and girls. Few people do this, but I've had good luck with it. Create a poster/handout promoting the panel, use it on social media sites, and make some copies. Remember to include the date, time, and location!

THE BIG DAY

10. Location location location. Check out the room in advance.

11. Gather the flock. You have checked in with your panelists, right? Made sure they arrived and know where the panel is? If you want to meet in advance in the green room, don't assume they know that.

12. Spread the word. If you created poster (see #9 above) put copies on the handout tables, and attach one at the entrance to the room. Maybe attach more on other walls around the facility if it seems appropriate.

13. Scene of the Crime. When you arrive at the meeting room make sure the microphones are working. Are there fresh glasses and water pitchers?

14. Volunteers of America. Is there a volunteer whose job is to warn you when the panel time is nearly over? If so they will probably introduce themselves. Make sure you know where they are sitting so you can catch their signals.

15. Don't call us. Remind the audience to silence their phones. At one panel the moderator's phone rang!

| |

| Bouchercon 2017 |

18. Watch your language. A male moderator (much younger than me) frequently referred to his all-female panel as "the ladies." I was not the only person who asked themselves "What century is this?"

19. Know your place. Chances are that you wouldn't be moderating the panel if you weren't interested and well-informed on the topic, but this is not about you and you are NOT a member of the panel. I am not an absolutist here; I will stick my oar in if I have something to add (especially in response to a question from the audience) but if I am talking as much as the others I am doing it wrong.

At one conference I served under a VERY chatty moderator. Later a stranger told me "I saw your panel. I wish I had gotten to hear you."

20. One for all or all for one? Some moderators prepare individual questions for each panelist. That can work (especially if the moderator knows a lot about each individual and their work) but to my mind it cuts down on interaction between the members. One tactic I like is asking individual questions as part of the introductions, and then switching to general questions.

21. Switch it up. Don't ask the same person first every time. If your first question is asked to A, then B, then C, then D, start your next query with B, etc.

22. One at a time. It may seem like a good idea to put the follow-up in the original question: "What characteristics does a good sidekick need? And how does a sidekick differ from other secondary characters?" But now you have the panelists trying to sort through two topics at once and remember Part 2 as they explain Part 1. Make it easier on them and you can always ask follow-ups if it seems appropriate.

| |

| Left Coast Crime 2019 |

23. A word from our sponsor. BEFORE you take questions from the audience, do the "outro." Thank the panelists, the volunteers, and the audience. Make any important announcements, such as when/where the panelists will be signing books. (I screwed up that one at LCC.) This way you don't have to worry about running out of time.

25. Lay down the ground rules. (If you use the experimental method I describe in 16 above, the following doesn't apply.) Before throwing it open to the audience I always remind them that this is an opportunity to ask questions, not to make comments, however brilliant those comments might be. And I quote moderator Ginjer Buchanan: "If your voice goes up at the end that doesn't necessarily make it a question."

26. Be the people's voice. Chances are you will have a microphone and the audience member won't, so repeat the question so everyone can hear. This also allows you to clarify a rambling query.

27. Never complain, never explain. If the crowd is smaller than you were hoping, don't apologize and don't complain, especially not to them. As a musician friend says "We play for the people who show up, not the ones who don't."

AFTERCARE

28. How was it for you? Email the panelists within a few days of the conference and tell them how wonderful they were. Send individual messages, not one-fits-all. Ask them if there was anything you could have done better.

That's all I can think of. If any of you have been on a panel, or moderated one, or attended one, I'd love to hear your suggestions.