From about age eight, I devoured science fiction with a passion. If I’d read Arthur C Clarke’s ‘The Sentinel’ then, I didn’t recall. Certainly I wouldn’t have guessed it would inspire arguably the finest science fiction film of the past half century. I didn’t make the connection at the time.

Nothing was going to stop this impecunious Greenwich Village student from seeing 2001: A Space Odyssey. For one thing, few critics and even fewer directors understand ‘hard science’ fiction. Those meager numbers unsurprisingly thin as a shrinking percentage of the populace take science itself seriously.

Back in April 1968, articles and advance marketing drove the buzz in New York City. Writers droned on and on about the beauty of the space ballet. Computer trade journals discussed the technology of HAL. Gossip columnists debated how to pronounced the lead actor’s name. New York’s theatre scene gushed that the chimps were portrayed by dancers. Much later we’d learn they were acted out by professional mimes.

Within days, the excited film talk turned to disillusion and disappointment. Even SF fans emerged from the premier saying, “Huh?”

WTF?

Foremost, the original cut fell victim to that movie-goer tendency to rush from a theatre before the first credit rolls. (The credits stampede has become such an annoying phenomenon that some directors reward fans who sit through until the end with further scenes.) Back then, fatigued by 2001’s seemingly endless ‘acid trip’, theatres emptied moments before the crux of the story revealed itself. Audiences missed the entire point of the story.

Stanley Kubrick sliced and diced the ‘acid trip’ (now called ‘star gate’) and reworked the production’s final few minutes. Even so, readers had to wait for Clarke to finish the novel written in parallel to piece together the entire affair. Clarke’s earlier 1948/1951 short story wouldn’t prove helpful at all.

Down the Wrong Path

As a penniless student, I refused to miss a second of the film’s original two hours, forty minutes. Although I remained through the ending, I left confused for a different reason. Not until the book came out did I realize a common story-telling technique misled me:

Showing, Not Telling

To demonstrate I wasn’t the only person led astray, I quote Wikipedia:

| “ | In an African desert millions of years ago, a tribe of hominids is driven away from its water hole by a rival tribe. They awaken to find a featureless black monolith has appeared before them. Seemingly influenced by the monolith, they discover how to use a bone as a weapon and drive their rivals away from the water hole. | ” |

|---|

That happened, but that’s not what happened. To flesh in more detail:

| Following the unveiling of the monolith, these ancestral apes take up long bones as clubs. In a slow-motion orgy of destruction, they bash discarded skulls into shards. In the next scene, they enthusiastically wield clubs to kill their hated enemies. |

That key led some to a false conclusion:

The monolith triggered violence and aggression.

The writers had intended the scene to show:

The monolith precipitated evolution.

No one knows how many viewers interpreted the scene wrongly. Between that problem and the abortive rush-out-the-door ending, Kubrick and Clarke managed to confuse an entire city and probably an entire nation.

Afterword

I hazard the filmmakers became blinded by proximity– they’d grown too close to that vignette to realize it could lead to misunderstanding. A fix could have been easy.

- The primates drive away sabre-tooth tigers or woolly mammoths, not a warring primate clan.

- The primates learn to dig, devise, or divert water using their evolving brains, not brawn.

Afterward

Nonetheless, I love 2001. Revisions have clarified and far more answers are available now than on opening day.

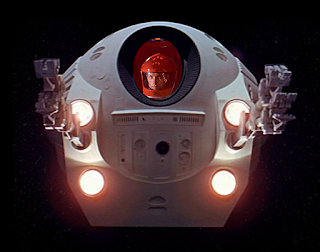

Months later, I would see another of my favorites in that same theatre district, Silent Running. About the same time while still on a student budget, a faded poster lured me to spend a couple of hours in a drab Greenwich Village dollar theatre, an elephant graveyard of soon-to-be-forgotten films. Filmed on a shoestring budget, that obscure celluloid strip turned out a gem in the rough. THX-1138 was the product of an unknown 24-year-old writer/director… George Lucas.

Arthur C Clarke’s short story? After seventy years, it shows its age, but it’s worth reading. We’re pleased to bring you ‘The Sentinel’ PDF and MP3/M4B audiobooks. You can also read or listen to 2001: A Space Odyssey provided for free by the thoughtful people at BookFrom.net. To listen or download, don't be misled by the nearby ‘Text-to-Speech’ icon, but click on the Listen 🔊 link in the upper right corner of the page.