- Do you know how to pierce the heart when you stab someone from behind?

- Know three commonplace items you can substitute for a silencer?

- Have a list of slow-acting poisons you can buy without a prescription?

- Have you ever discussed such things with friends over dinner at a restaurant?

You must be a mystery writer.

Mystery writers run neck and neck with murderers themselves in preoccupation with ways to kill. Unlike actual assassins, for whom discretion is both a tool of the trade and essential to staying alive, writers love to discuss these matters with their peers. Before the pandemic, when convivial dinners were the high point of monthly meetings of my local Mystery Writers of America and Sisters in Crime chapters and I went to mystery cons all over the country, I looked forward to such discussions and participated with great relish. If they took place in public places, so much the better. It was great fun to imagine the party at the next table wondering what you were plotting, a real-life crime or just a story. I admit to a tad of vestigial adolescent exhibitionism, what I call a Look, Ma! element in keeping eavesdroppers guessing.

One of the most beloved figures in the mystery community is Texas pharmacist and toxicologist Luci Zahray, universally known as the Poison Lady. When I sat down to write this, I found a note in my files, Poison Lady—arsenic (Walmart story). I probably jotted it down as she spoke at a Malice Domestic a decade before. I remembered the gist of it but wanted to get it right, so I emailed her. The Poison Lady’s own words reflect how not only writers but mystery lovers in general think.

The year arsenic became illegal to sell in stores, I was walking through Walmart and they had a grocery cart full marked down to 50 cents a box. I naturally, as one does, started pushing the cart to checkout. Then I realized I didn't actually need that much arsenic or even have a good place to put it. So I picked out several, quite a few, boxes and bought them. I still don't need that much arsenic and don't have a good place to put it, but I sometimes regret not buying the whole cart full.

We’re equally interested in likely settings for murder and places to bury the body. For example, what's buried in the garden? My son recently told me that the sale of his in-laws’ house in New Jersey was held up because they discovered an oil burner buried in the backyard. I was charmed. An oil burner is dull, but what if there were a body in an oil burner? Even better—hold the oil burner.

Back in the Golden Age of mysteries, cleverness was valued more than it is today. John Dickson Carr was the king of the locked room puzzle, which depended on unexpected murder methods. Sherlock Holmes solved one case in which the lock was breached by a poisonous snake slithering through a pipe in the wall, if I remember correctly.

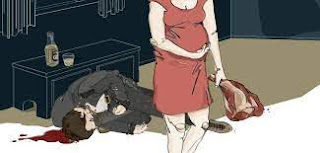

Roald Dahl’s short story, “A Lamb to the Slaughter” (1953), in which the murder weapon is a frozen leg of lamb, later cooked and served to the unwitting detective, is often cited as the best murder method in mystery fiction.

In Fried Green Tomatoes at the Whistle Stop Café (1987)— the novel, on which the movie was based— Fannie Flagg rang a change on this. The murder was a simple skillet to the head. But the body disposal took place in the kitchen, and once again, the detective dined on the results.

Do we still relish ingenuity in the means of our fictional murders, or have we become so jaded that it doesn't matter any more?

To some extent, it varies according to subgenre. If it’s a cozy, the murder may be death by wedding cake or the victim stitched to death into a prize-winning quilt. If it’s Kellerman or Cornwell or their ilk, there’ll be a lot of gore, maybe torture described more lovingly than I want to read about. If it’s a technothriller, we’ll hear all about the gun and its accessories.

The best place to look for the far-out murder weapon these days is video. In shows like Midsomer Murders and Brokenwood, the giant cheese and unattended vat of wine are alive and well and killing people with enthusiasm. I get a kick out of watching and talking about these tricks. But in my own work, I like to knock the victim off quickly— bang on the head, push over the ramparts, car off the road— and get on with the story. For me, it’s not about the props. It’s always about the people.