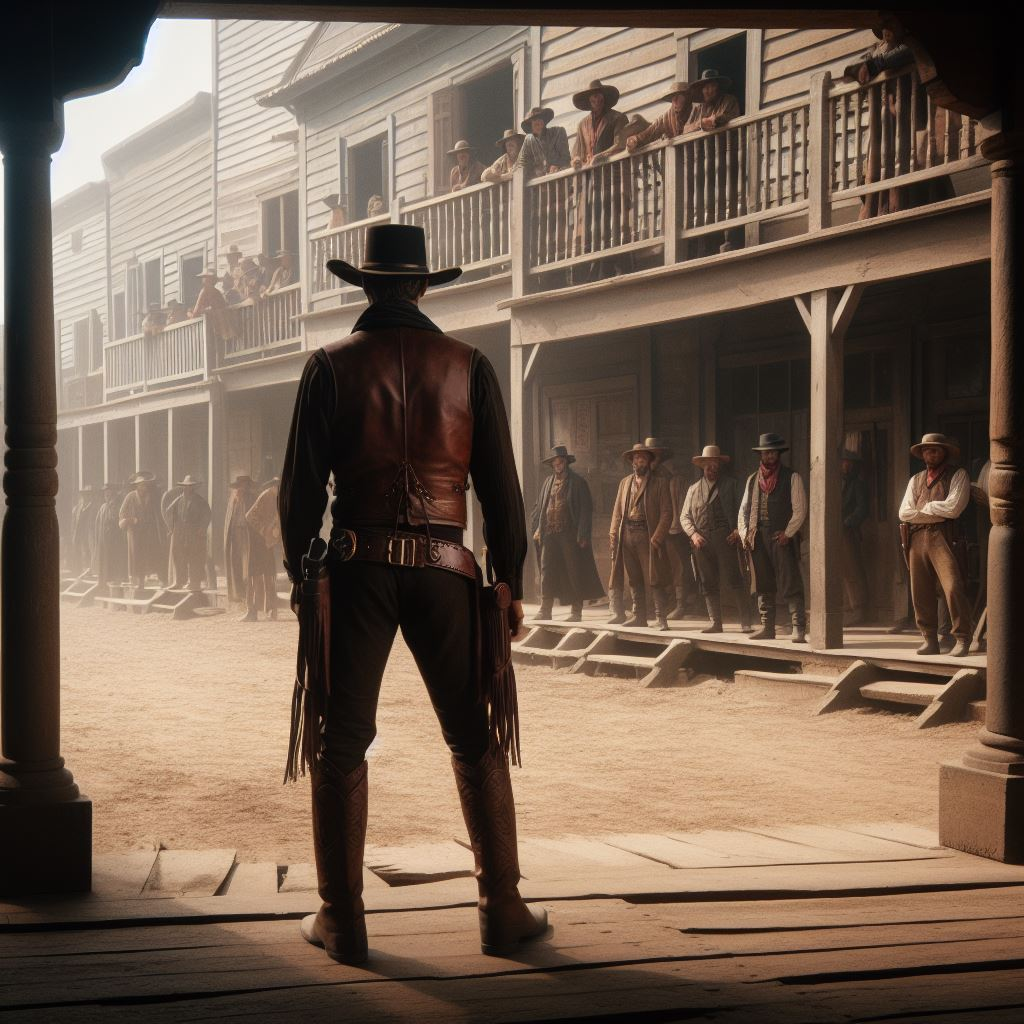

In a follow-up to the previous article about Western movies, what does Niels Bohr have in common with Lee Van Cleef and Clint Eastwood?

Western quickdraw gunfights.

To be sure, few human endeavors (okay, male endeavors) are more idiotic than gunfights. I can’t imagine the genius who said, “Okay, boys, arm wrestling is fun and all, but we need more excitement. You and you, set down your beer, go out in the street, and shoot one another.” Then everyone (okay, males) cheered and chortled and ordered a further round of drinks before staggering out in the dusty avenue to burps and bangs, sparks and splatter.

Eventually Mother Nature winnowed the pool of foolish candidates. No doubt a few wives told husbands, “Your choice, Henry: At high noon, you can meet Pete in the street or join me at the train station where I’ll board the 12:05 back to my mother in Ohio.”

Later at the Short Branch Saloon:

“Henry, you yellow jelly-bellied, lily-livered, mutt-butt, rotted snivel-snotted, slimy slug of a coward, what do you mean you ain’t gonna gunfight me?”“Uh, my wife gave me an ultimatum: show or go.”“Did she? Listen, Henry, don’t tell no one, but Alma tole me same thing. She said I shoot you, she shoot me where I will live to regret it.”“Did you mean what you said about jelly-belly?”“Nah, that was whiskey talking. But the part about your mutt-butt, how does your wife tolerate that ugly saddle sore ass of yours?”“Good to laugh, Pete. What say we get a drink, maybe invite our ladies like we used to?”

Reactive Advantage

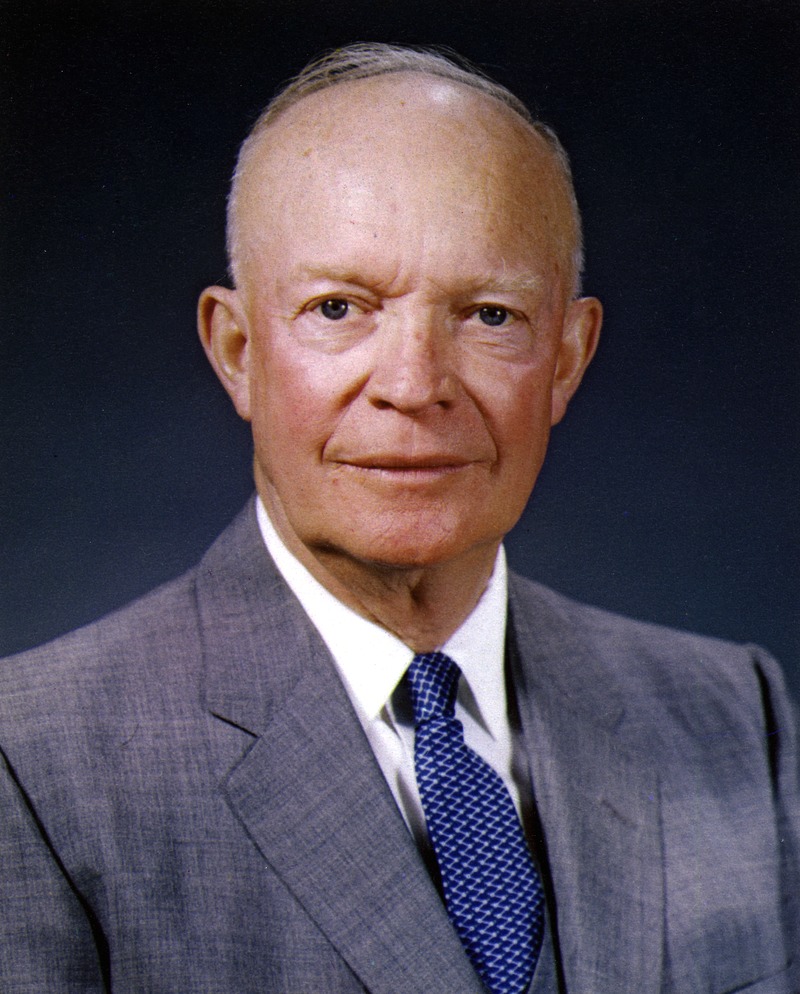

Niels Bohr, Nobel prizewinning physicist, and contemporary and colleague of Albert Einstein, studied quickdraw gunfights. He wanted to know why the man who shot first died… at least in the movies. Bohr hypothesized initiating action takes more time than to react to the same movement.

Researchers call this reactive advantage. If you’ve ever seen a viper versus a cat, rabbit, or mongoose, the serpent rarely wins. The little furry animals are generally far faster than snake strikes.

A few years ago, neuroscientist Andrew Welchman of the University of Birmingham studied Bohr’s experiments. He worked out a simpler experiment and concluded Bohr was on the right track. Although Bohr won every faux gunfight (with toy pistols), there’s a little matter that it takes the brain about ten times longer to launch the reaction than the actual execution.

The Quick and the Dead

As mentioned last time, I very much like the second film of the Eastwood man-with-no-name trilogy, For a Few Dollars More. I felt it portrayed a flaw in the gunfight premise. In the movie, Lee Van Cleef and the bad guy wait for a musical watch chime to run down, after which the shootout begins. I wondered why wait? As the watch plays, why not draw, go bang, and apologize later. “Oops, I thought the music was done. My bad.”

I mean seriously? The bad guy is about to kill you. Why leave anything to chance?

At the risk of affronting my betters, I suggest two problems with Welchman’s and Bohr’s supposition.

Perhaps it made little difference, but in their experiments, no one’s life was on line. After their laboratory rundowns, they shook hands and went home for the night. They couldn’t feel the pressure of life or death. Also, many real-life shootouts were alcohol fueled, which could factor in.

Returning to For a Few Dollars More, in the beginning, a bad guy flees bounty hunter Van Cleef. He hops on a horse and gallops down the street.

Van Cleef unhurriedly strolls to his horse and unrolls a small arsenal. He selects a revolver with a long barrel, takes careful aim, and judiciously pulls the trigger.

Bad guy falls from his horse, but Van Cleef again takes his time, sights the baddie, and bang, he’s down for good. The scene represents a lesson learned from duels: Take your time. A duelist who shoots rapidly may compromise aim. One who takes his time can aim carefully while the other remains frozen.

Wyatt Earp agreed. He wrote, “The most important lesson I learned was the winner of gunplay usually was the one who took his time.”

The were admirable exceptions in the dark world of duelling. Occasionally a duelist would deliberately fire into the ground, leaving his opponent the moral dilemma of wreaking death or mercy. A wise choice, especially when combatants were former friends.

After the Show

In the early 1900s, gunmen (and Annie Oakley) who survived found themselves in Wild West Shows where they showed off their skills along with trick riders and rambunctious stage coach robberies, à la, WestWorld. As mentioned previously, my father as a child became acquainted with the last of the fancy shooters. They could literally shoot coins tossed in the air.

Several years ago at a fair, I watched a quick-draw artist do his thing. He extend his right leg well forward so that his thigh was pointed toward and about even with his target. His draw and reholstering was so fast, it was barely a blur. The suspicious part of my mind wondered if it was a magic trick, one where he pretended to draw and reholster, while a bang sounded and a hole popped in the target.

On the other hand, a woman at the back of the tent sold VCR tapes. They could be slowed and studied frame-by-frame, which argued against trickery, a damn fast 20ms. What do you think?