Atticus Finch Has Left the Building

What I found was Payback, a 1999 movie with Mel Gibson. I remembered watching it years ago, and remembered it mainly because he played a thief named Porter, a renaming of the "Parker" character created by the late Donald Westlake. This movie was in fact a remake of the 1967 film Point Blank, with Lee Marvin, which was adapted from Westlake's novel The Hunter. Anyhow, something like that sounded just right for both my temperament and my timeframe, that night. I remembered something else about the appropriately-titled Payback, too: its logline (the little teaser phrase that had appeared on the movie posters and the DVD boxes) was "Get ready to root for the bad guy."

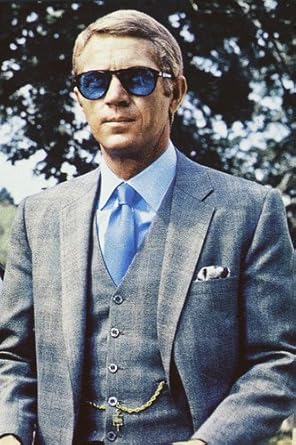

Root for him I did. The casting helped, of course. Mel Gibson, like James Garner and Tom Selleck and Steve McQueen and Burt Reynolds and George Clooney and Paul Newman and a very few others, is hard to root against--even when he's an outlaw and a killer. Beyond that, though, I found myself wondering if there might be a lesson in the plot, for mystery/crime writers. It seems that's it's okay for your protagonist to be a bad guy as long as (1) he has some kind of personal code of honor regarding right and wrong and (2) there are others in the story who are even worse than he is. Hoping that your readers will sympathize with your hero/heroine just because he/she is the lesser of the evils would appear to be a risky business, but it seems to work. Of the four short stories I have coming out soon (EQMM, Crimespree, The Saturday Evening Post, and an anthology), all four feature criminals as the main characters--and I think they were even more fun to write than if they'd had regular law-abiding protagonists.

The Good, the Bad, and the Questionable

The Good, the Bad, and the QuestionableAs you might've expected, I've put together a list of some unlikely heroes that movie and TV audiences pulled for:

- Tony Soprano

- Michael Corleone and family

- Bonnie and Clyde

- Thelma and Louise

- Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid

- Chili Palmer, Get Shorty

- Henry Hill, Goodfellas

- Vincent Vega, Pulp Fiction

- The cat people in Cat People

- Thomas Crown

- Danny Ocean

- Hud Bannon

- Cool Hand Luke Jackson

- Cat Ballou

- Walter White, Breaking Bad

- Verbal Kint (Keyser Soze), The Usual Suspects

- Most characters in any Quentin Tarantino film

- Most characters in any Quentin Tarantino film- Most characters in any adaptation of an Elmore Leonard novel

- Marion Crane, Psycho

- Fast Eddie Felson, The Hustler

- Abby Marty, Blood Simple

- Stuntman Mike, Death Proof

- The Man With No Name, Sergio Leone's westerns

- Jaime Lannister, Game of Thrones

- Those trying to get away in The Getaway

- Pete "Maverick" Mitchell, Top Gun

- Red and Andy, The Shawshank Redemption

- The three escapees in O Brother, Where Art Thou?

- The two stingers in The Sting

- William Munny, Unforgiven

- Django, chained or unchained

- Pike Bishop and his Wild Bunch

- Nancy Botwin, Weeds

- Frank Underwood, House of Cards

- Frank Underwood, House of Cards- The heated bodies in Body Heat

- Snake Plissken, Escape From New York

- Frank Morris, Escape From Alcatraz

- Ben Wade, 3:10 to Yuma

- Nucky Thompson, Boardwalk Empire

Two questions. First, can you think of any good "bad" characters that I missed? (I intentionally left out borderliners like Han Solo, Shane, Ferris Bueller on his day off, etc., as well as otherwise good folks who went bonkers like Norman Bates and Jack Torrance and Annie Wilkes. And I know you're probably saying to yourself that Maverick in Top Gun wasn't really a bad guy. You're right, he wasn't--but he was an unlikely hero for that situation. He was a reckless, Smokey-and-the-Bandit troublemaker, a loose cannon rolling around on the deck, and that's usually not the kind of guy you want piloting an F-14.)

Second question. Do you as writers sometimes use bad guys as your protagonists? If so, why? If not, why not? I read somewhere that Lawrence Block had a few misgivings before launching both his Bernie Rhodenbarr (burglar) series and his Keller (hit man) series--probably because of how hard it would be to make those protags likable and acceptable to the reader. Thankfully, he did it anyway.

The Rise of the Anti-Hero

I haven't counted them up, but I figure at least ten percent of my short stories have featured lawbreakers, or at least lawbenders, as the main characters. Almost any heist story or revenge story relies on that, and I've done a lot of both. In that regard, I'm always comforted by the old saying that law and justice are two different things. I think readers will sometimes accept and forgive illegal behavior if it's done for the greater good and if the end justifies the means. That's probably the sole reasoning behind the series Dexter, as well as the reason for its success.

I haven't counted them up, but I figure at least ten percent of my short stories have featured lawbreakers, or at least lawbenders, as the main characters. Almost any heist story or revenge story relies on that, and I've done a lot of both. In that regard, I'm always comforted by the old saying that law and justice are two different things. I think readers will sometimes accept and forgive illegal behavior if it's done for the greater good and if the end justifies the means. That's probably the sole reasoning behind the series Dexter, as well as the reason for its success.The thing is, even when our heroes are basically good men and women, they're rarely perfect. Rick Blaine was an alcoholic, Inspector Clouseau an idiot, James Bond a stone killer, Sherlock Holmes a drug addict, Randall McMurphy a nutcase, Conan a barbarian. In our real lives we try to choose as our friends people who are sane and kind and honest and decent; in our fictional creations we (writers) try to choose as our characters people who are not. As Nicolas Cage said to Holly Hunter in Raising Arizona, this ain't Ozzie and Harriet.

Another quote. In an online article called "The Rise of the Anti-Hero," pop-culture enthusiast Jonathan Michael said, "Perhaps it's the darkness that reels us in, because we relate to the darkness. But even so, we hope for the light."

Tell that to Hannibal Lecter.