Last Saturday evening, I dined in a real restaurant for the first time since the coronavirus broke upon our shores. That same evening at the same restaurant in the heart of Orlando’s International Drive tourist center, a man was murdered.

It didn’t particularly surprise anyone. Most attendees expected something of the sort because homicides occur frequently at Sleuths Mystery Dinner Show.

|

| Our show, not our cast |

The occasion was Haboob’s birthday party arranged by her daughter who invited me (thanks, Kathy). I’d never attended a mystery show and looked forward to it.

Murder 1

The first mystery involved parking. The car lot was full. Shops and restaurants surrounding the theatre share a garage with Icon Park, a 20-acre entertainment complex, which includes a Madame Tussaud’s and a London Eye-type ride called The Wheel, approximately 122m (~400ft) in diameter.

Here, developers confused ‘arcade’ and ‘parkade’. The garage is loaded with exit signs, none of them useful. This results in cars milling like microbes, trying to decipher a way out. One unfortunate Hyundai has been circling since 2017. Family members rope up buckets from below and tote gasoline up stairs to refuel it. My friend Geri and I could have happily murdered the garage’s architect, but mayhem was supposed to occur in a dining establishment, not a garage.

|

| A constable Connie, not our scare-your-pants-off Connie |

Murder 2

Sleuths operates two theatres and we found ourselves led to slaughter in Theatre II, a surprisingly large hall with a shallow stage along one side. There, a couple of dozen round tables accommodated up to ten guests. Real tablecloths, cloth serviettes, and real butter provided nice touches.

Let it be said, visitors don’t come for the dining experience. Chicken and vegetarian options were available, but our entire party ordered prime rib, a $6 extra disappointment. I could offer two or three smartass comments, but the less said, the better. Our neighbors ordered lasagna and voiced no complaint. Desserts were tasty and the wine was unexpectedly drinkable.

Waitress Nicole supplied us with tea and soda, and as far as I could discern, took no notes when doling out drinks and desserts to the correct parties. While I’m in a complimenting mood, thanks to Miss DeSantis (no relation to our dreadful governor) for help, kindness, and patience making reservations.

Staging a Death

In interactive murder mysteries, guests participate in the experience. They mingle with victims and suspects, and handle and inspect clues. This was not those.

Rather we are presented with one of five abbreviated plays, a comedy where four actors play five rôles. The skit takes place in an English Inn, placing the actors at risk of murdering the mother tongue worse than I. Fortunately, the cast treats dialect with a light touch.

|

| Late update! @ Chris Sowers The REAL Constable Connie who owned the rôle |

We meet the characters. Murder ensues. The law makes her entrance.

Holy Chautauqua!

The clear star of the show is Constable Connie Crabtree, whose actor also plays the crotchety murder victim. This doesn’t tell half of it and the masculine noun is not an affectation. Although the victim is male, the constable is female and… no, wait. See, the heavily made-up and considerably frightening Constable Connie is played in drag by an actor I wouldn’t want to meet in a dark alley.

But funny, hilariously funny. Political correctness has robbed our society of so much humor, it’s refreshing to let down our guard and enjoy witty innuendo and double entendres without clubbing us with correctness. God save the Queen.

On With the Show

The play draws to a close. The cast invites the audience to help solve the mystery by formulating questions– one per table– of the characters, mostly concerning conversational threads left dangling.

The audience was paying attention; several queries were highly pertinent. Despite my great renown as a world famous SleuthSayer, my question about parentage wasn’t chosen by my table, although it turned out to be the heart of the mystery. (So there!) Constable Connie’s acidic tongue kept questions moving, especially when a couple of tables had enjoyed a bit too much of the not-too-bad wine.

|

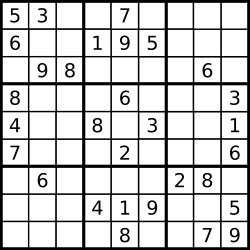

| mystery worksheet |

WhoDunWhat?

The play is not The Mousetrap. I found two chinks in the mystery itself, both unexplained gaps– or sudden leaps. Actors abruptly drop a comment that the victim fathered another character without us being previously presented with that fact. In the free-wheeling delivery of the play, was it overlooked?

Likewise, the audience had almost universally settled upon one cast member as the murderer, but the constable informed us it was quite another without linking evidence. Unless another clue had been left out, the choice of perpetrator seemed almost random. Perhaps we missed hearing a hint, but if we did, so did our half of the room.

I haven’t seen the script, but possibly a bit or two was inadvertently omitted. Still, we figured out the key to the plot and motive, and besides, the real point was the comedy. You don’t read Janet Evanovich for the plot, you read her stories for the laughter. Same with this play, Squires Inn.

Mouths of Babes

A number of young children sat near the front and loved it. Although one character in the play had paid heavily and labored for years to purchase the inn, the play’s sole woman (not counting Connie) inherited it, leaving the man with nothing. The constable asked the kids if the woman should share the inn with the man and they– almost entirely girls– shouted out a resounding No!

Oh sheesh. They’ve been listening to their mothers.

The theatre awarded birthday gifts and door prizes of a surprisingly useful magnifying glass. That was a superb touch.

At nearly 10:30 that night, I helped Geri find her car in the garage. I am not in the least kidding– cars were still queued snailing on the third level, trying to find their way out.

Verdict

From the viewpoint of a professional crime reader and writer, Squires Inn didn’t come off as a fair-play mystery with clues that pointed unambiguously to a single perpetrator. But as Hamlet said, “The play’s the thing.” It is a lot of fun and definitely worth the trip. You might not solve a mystery, you could die laughing.

Have a happy and safe 4th of July!