Penguin/Random House has reissued John D. MacDonald’s twenty-one Travis McGee novels in nicely-packaged trade paper, with tasteful cover art and a preface by Lee Child.

I might prefer some of the more lurid original jackets, not quite so restrained, but I admire the enterprise. Some of MacDonald’s books, Slam the Big Door, or One Monday We Killed Them All, even The Last One Left, have been in and out of print, over the years; McGee has never fallen out of favor.

I don’t think it’s any secret that MacDonald was reluctant to do a series character. It was Knox Burger, at Fawcett Gold Medal, who convinced him. MacDonald was getting along just fine, by all accounts, knocking out a couple or even three novels a year, and then McGee moved the goalposts. It took half a dozen books, but Travis McGee turned John D. MacDonald into a brand name.

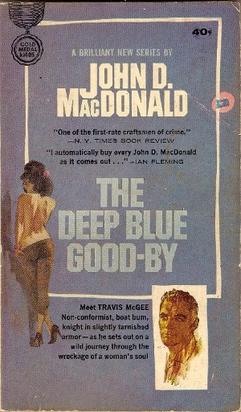

This is a phenomenon that I’m guessing is particular to the time. Gold Medal was a paperback original imprint, like Ace, which put out SF titles in a double-novel format, two books back-to-back. It was the Republic Pictures of the publishing business. Paperbacks had come in big during the war, cheap editions for GI’s. Pocket Books was an early entry, and postwar, publishers realized they could expand the market to drugstores and newsstands, railroad stations and airports and hotel lobbies, and avail themselves of the impulse buyer. The books cost a quarter, in the 1950’s, and in ‘64, The Deep Blue Goodbye, MacDonald’s first McGee title, sold for forty cents. They were below the salt, mind you. The New York Times Book Review didn’t deign to acknowledge paperback originals; they were pulp, they were Poverty Row. And they were mostly generic, hardboiled noir and science fiction, women in prison or youth led astray.

Readers gobbled them up. Granted, our tastes might not have been that discriminating. I ran across The Deep Blue Goodbye at a PX newsstand when I was in the military – dating myself – and I grabbed every single book afterwards as soon as they came out.

The visceral appeal, for sure. The laid-back life, the long sunsets, ice clicking against a tall glass, the careless, carefree women. It was an adolescent fantasy. There was something darker, and more subversive. MacDonald was one of the first guys, along with Frank Herbert in Dune, to talk about the environment.

One of the constants in the McGee books (and in MacDonald’s later stand-alones, A Flash of Green and Condominium) is the greed and waste of accelerated development. No wonder that Carl Hiassen counts MacDonald as an influence.

And the deeper, yawning, reptilian darkness. The sexism was backward and Neanderthal; the environmentalism was forward-looking; the bad guys are psychopaths. McGee, by his own admission, is a throwback. If he weren’t, he wouldn’t be able to handle the bottom-feeders and predators that lurk, not on the periphery, but in plain sight.

Bad guys, in a McGee novel, aren’t ambiguous. They may be sly, or slippery, or possessed of a certain charm. Nor are they, necessarily, guys.

But there’s a clear line MacDonald draws: the luckless, the gullible, the innocent, don’t deserve to be shorn simply because they’re sheep. We protect the weakest, by reason of their very weakness.

Reading the books again, and not in order - the first one I picked up was The Scarlet Ruse. I’m struck by their economy. There’s no wasted motion.

Dutch Leonard says you should leave out the stuff the reader’s going to skip, and you don’t care about, either. You can see Leonard do it, and Hiassen, or Lee Child.

Stay with the essentials, spend your energy on the parts that matter.

In other words, if it holds your interest, it’ll show. If you’re going through the motions, you’ll bore yourself, and the reader.

The set-up for The Scarlet Ruse is relaxed but brisk. First, the rare stamps. We’re perhaps reminded of the Brasher Doubloon. “The only known vertical pair of the famous error in blue… The top stamp has one pulled perf and a slight gum disturbance.”

Then, the switcheroo. Who had access to the safe deposit box? Next, the whys and wherefores of the investor, who turns out to be mobbed up, a money launderer who’s skimming, and the stolen stamps, in demand and fungible, represent his getaway money.

For a hook, so far, so good. But this is just the bottom crust, not the filling. It isn’t the story MacDonald is interested in telling. The real story, once the broad brushstrokes are laid in, is about trusting the wrong people, and each relationship, McGee and Meyer, McGee and the damsel in distress, McGee and the heavy, for that matter, is dependent on good faith or bad.

The final trap, the ruse of the title, is in effect a pigeon drop.

The moral, as in every McGee story, is about ownership, and personal responsibility, whether the results work to your advantage or not. Once you set events in motion, you have to live with the consequences, and those consequences can be severe. McGee’s world isn’t Manichean, or absolute, and black and white are often blurred, but the choices tend to narrow toward the violent and final. You can argue this is characteristic of the genre – when you run out of ideas, Hammett tells us, have a guy come through the door with a gun - but here the violence isn’t lazy, it’s exhausting and inevitable.

He was very much of his time, let’s be honest. MacDonald and McGee flourished during the Cold War, but unlike the nihilism of Spillane and Mike Hammer, actual events don’t much impinge on McGee’s world.

There’s a sidelong look at the Markov assassination in The Green Ripper, ricin being the instrument of choice, but generally, what’s going on in the larger political atmosphere isn’t pertinent. What is, is a sense of growing malaise.

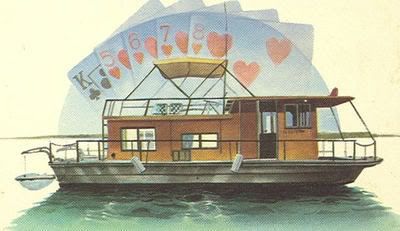

McGee seems lonelier as time passes, more isolated (excepting Meyer). The Green Ripper, actually, finds him completely out on a limb, with no support system whatsoever. Not that he isn’t the archetypal loner, in many ways, but he’s also embedded in a personal ecology, the marina, the houseboat, the culture of south Florida and the offshore islands.

This context is vital and specific. Taken without it, McGee is himself less specific. So, although contemporary events may not affect the characters directly, the place, the weather and the water, the color of the sky, the heat in the air, the pull of the tides, provides a canvas. Not as backdrop, but as a constant, the horizon line, the curve of the earth.

Do the books age well, does McGee have legs? I’m not the guy to ask. He’s a sentimental favorite. There are things that are awkward and squirmy – truth to tell, they were awkward and squirmy back when – and there are things that make you pump your fist and go, Pow! John MacDonald is as rock-solid a writer as they come. Is it pulp? Depends. It’s vigorous, and brassy, and hot to the touch. You don’t get much better.