When most people say Old English, they're actually referring to Elizabethan English. The type found in Shakespeare and the King James Bible. The markers are the formal vs. informal second person and the attendant verb forms. "Thou," informal for "you," is rarely used these days, though the objective form, "thee" still puts in an appearance here and there.

|

| Miramax |

But that's not Old English. That is merely an early form of modern English. You know. What you're reading this very moment. "Thee" and "thou" had a long, slow decline to the point where they still exist, but they often are used for effect. Some even think "thee" and "thou" are more formal. And yet the Spanish version of "thou" is tu, and my high school Spanish teacher informed us calling a total stranger tu was a great way to get slapped. Those speaking Romance languages take the separation of the familiar and the formal very seriously.

On the other hand, the late Queen Elizabeth and King Charles seem to have been annoyed by the royal "We," but questions of gender identity and the lack most languages have of a gender-neutral pronoun beyond "it" (which is awful for referring to people) has given rise to a singular "they." Some find this controversial. I find this the perfect excuse to dance on my tenth grade English teacher's grave.

But what is Old English, then? And, for that matter, Middle English?

|

| By PHGCOM - Own work by uploader, photographed at the British Museum, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=5969131 |

Old English actually refers to Anglo-Saxon, the tongue that evolved from the Germanic of the Angles and Saxons who moved in after the Romans pulled out of Britain and the Norse of the Jutes, who had a great idea. They'd leave Scandinavia and build this colony called Kent, where one day, teenage blues nerds would reinvent rock and roll. Anglo-Saxon was a Germanic language, sounding quite a bit like Dutch with a syntax resembling Yoda speak. It even used a not-entirely Roman alphabet.

My youngest stepson used to complain loudly about the silent "k" in "knight" or "knife." I used to blame the Vikings, who added more Norse to the language. Silent "k" does not make linguistic sense in the context of English rules, so it must be their fault. Right? Nope. Silent K came over from Germany with those Angles and Saxons. The Celts, who'd been in Britain since before the Romans, shrugged and started using it when they dealt with the weird Germans (and those guys over in Kent. Who are still quite Kentish.)

The best example of Anglo-Saxon is the epic poem Beowulf. It has to be translated for modern audiences because the English of Alfred the Great is not even the language of Edward III, one of the first Norman kings to actually speak English to his subjects. As I said, the alphabet is different. The syntax is different. It's really another language. But it's not. It's just the prototype for what you're reading right this moment.

The translation of Beowulf I listened to on Audible was done by a translator from Ulster. Ulsterites are in a unique position when it comes to English, steeped in two flavors of Celtic languages along with English. This particular translator also spoke Irish. So sometimes, he used a Celtic interpretation of certain passages to translate into modern English.

,_frontispiece_-_BL.jpg) |

Geoff Chaucer, renaissance man

before the Renaissance

|

Then we come to Middle English, the language of Chaucer. And the language of Sir Thomas Malory. Chaucer we know because he was the BFF and brother-in-law of John of Gaunt, the ancestor of the current royal family. Chaucer was a regular renaissance man before there was an actual renaissance in England. (The plague had yet to wipe out a third of Europe.) Malory has been traced to one person, but might have been several.

Anglo-Saxon was the predominant language in Britain for 700 years, from the withdrawal of the Romans to the Norman Conquest. Strange folk those Normans. They were Vikings. But not the Vikings of Sweden, Denmark, or Norway, nor the funny-talking English of the Danelaw, in central Britain. No, these Vikings had settled in France, started speaking French, and had radical ideas like banning serfdom and writing things down. From William the Conqueror (a much better regnal nickname than William the Bastard, which he was called as Duke of Normandy) to the final days of the Plantagenets, the court spoke French. The Church spoke French. Business was conducted in French. Anglo-Saxon faded because French was more compatible with Latin, then lingua franca. (Ironically, the term refers to French, a Latin-based language.) So English had to adapt.

If you go slowly, you can probably read the original text of The Canterbury Tales, Chaucer's sprawling series of tales from a cross-section of English society. (And I really want to pour a glass of wine over Prioress's head, but I was born around the time the Beatles because a studio-only band.) I said almost read it. The words, when read aloud, are somewhat familiar, but the spellings are almost phonetic. It still requires a translation, but it's almost word-for-word.

Flash forward a century to Malory's Le Morte d'Arthur, and not only is the original text readable, it looks like Shakespeare trying for forge a few entries into The Canterbury Tales. Chaucer lived near the end of the twelfth century. Malory retold the Arthurian legend (actually, the Norman appropriation of a Saxon forgery of a Welsh legend about a guy who likely was a Roman) around 1485, according to William Caxton's note at the end. That's only seven years before Columbus took a wrong turn at Hispanola and declared Haiti to be Indonesia. (The Carib tribe found this a bit confusing as they'd never heard of the East Indies. The East Indians found this hilarious.)

Middle English arose during the Norman Conquest and became the language of peasants and merchants who didn't give a fig about their French overlords. Since, by the time of Edward III, England had few French possessions, his sons and grandsons decided an English monarch should speak, yanno, English. Chaucer codified a lot of written English, so you can blame him for the confusing "-ough" construction, a tough construct that can be understood with thorough thought. "Should," "would," "could?" Yep. That's Middle English, too. Thanks, Geoff!

But Malory's collection and retelling of Arthurian tales was published around the time some Welsh guy with a dubious claim to the throne named Henry Tudor ruled England. (And Wales. The Welsh found this hilarious.) Your eyes might cross, but you can actually read Le Morte d'Arthur in the original text. The spellings are Middle English, but aloud, it sounds more like Shakespeare. And why wouldn't it? King Hank would begat Henry VIII who would begat Elizabeth, who would hand off the throne to her cousin James. Modern English is emerging. Not there yet, but it's coming. Publishers still update the language because English from a century prior to The Tempest still challenges the modern reader.

Unlike Anglo-Saxon, Middle English's day was only 500 years long.

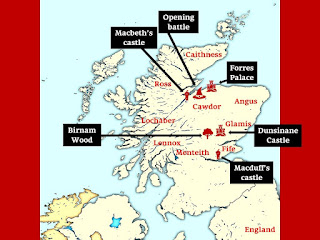

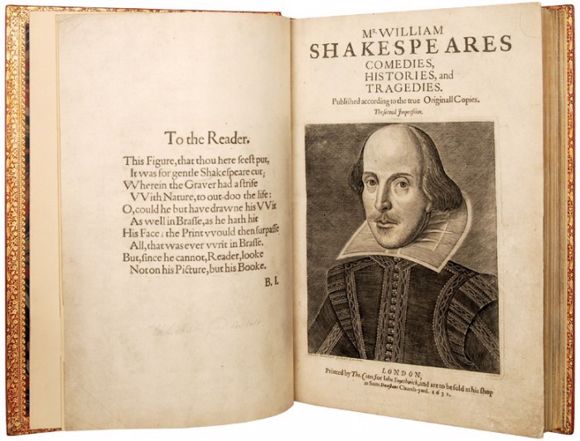

Then came Shakespeare. Credit a few other writers, including Marlowe, Francis Bacon, and so on, for joining Wil in codifying English. A few apocryphal accounts suggest English varied from town to town. But Wil's plays, along with Marlowe's and a few others', were performed widely. So, as folios and quartos became available via the printing press, English started to sound roughly the same with standard spellings taking root.

Of course, even then, it was not fate accompli. The informal "thee" and "thou" disappeared (though still spoken in parts of Yorkshire and Appalachia.) Americans changed the words "happyness" and "busyness" to "happiness" and "business." Writing from Washington, William Pitt the Younger, and Thomas Paine suggest spelling was more a guideline than a set of rules. In the late nineteenth century, a movement tried to simplify spelling, which changed "plough" to "plow" and "all ready" to "already." The movement, in my humble opinion, died out too soon, but Mark Twain now gets an edit when he isn't writing in dialog since he, like many of his day, disdained formal spelling rules. (But he had a hypocritical attitude toward adjectives.)

The point is, of course, English is an ever-evolving language. From a Germanic tongue with some Latin suggestions and the odd bit of Welsh or Cornish to a mashup of Anglo-Saxon reshaped by French, absorbing more Latin, and making up its own rules today's language, English, as many like to say, is not so much one language, but seven welded together and roving in a pack to mug other languages in a back alley. Originally, English was written in runes. The runes are gone, but now memes are creeping in. You only have to show a picture of a woman screaming at a cat to understand the gist before even reading the text.

What's next.

^Apologies to Quentin Tarantino, but I can't use the original line in this forum.

.jpg)

,_frontispiece_-_BL.jpg)