Pamela Beason wrote a piece for us not long ago and I wasn't expecting to have her back so quickly but when I read her novel THE ONLY WITNESS I loved it so much I invited her to write about it ASAP. And here she is. I think you will see why this unique idea appealed to me so much. - Robert Lopresti

When the Gorilla Takes Over

by Pamela Beason

When I began to write my novel The Only

Witness, I didn’t plan for it to be a series. Nor did I plan for Neema

the gorilla to be the protagonist of the book.

I was working as a

private investigator at the time, and I’d worked on several cases where

small children testified as witnesses. Now anyone who has worked with

young children, especially in a legal context, knows that they often

have limited understanding of the reality of what is happening to them

or around them, and we also know how easily they can be persuaded to say

the things that the adults want them to say. So, I had done a lot of

thinking about who can be a credible witness.

In addition to my

interest in investigation and legal issues, I’ve had a lifelong

fascination with animals of all kinds, and I’ve been especially curious

about animal intelligence. I always wondered why humans think we’re so

superior just because we can talk and write. All animals have their own

languages and talents. As a scuba diver, I’m amazed to see so many sea

creatures that can synthesize their own homes (shells) out of the sea

water that surrounds them, and I’m positively astounded to see an

octopus or a chameleon change the colors and patterns of their skins. My

cats can easily jump to the top of a wall that is seven times their

height. Tiny hummingbirds can hover in mid-air and survive the winters

along our coastlines. Animals make me feel inferior a lot of the time.

But

I digress… Getting back to the point, I’ve read all the books and

articles about teaching apes American sign language so we humans can

communicate in the only language we understand: The Education of Koko

and the films and National Geographic articles about the famous

gorillas, Roger Fouts’ Next of Kin, and some others.

So naturally my investigator brain got together with my animal-loving

side and cooked up the idea of having a gorilla, who supposedly has the

IQ of a five-year-old, be the only witness to a baby’s kidnapping. Cool

idea, right? But I resolved to keep the whole story plausible, so I had

to work with an ape’s limitations. A gorilla is never going to say, “You

know, when we were in town at 3 p.m. yesterday, I saw the most curious

incident when a shaggy-haired man…” So Neema’s clues had to be more

along the line of “Snake arm make baby cry. Give banana now.”

I

thought readers would sympathize more with beleaguered Detective Matthew

Finn, who initially cannot find any witness to what actually happened

when an infant vanishes from a car, and then, when he finally deduces

that he does have a witness, she’s a gorilla. How can he find out what

she actually knows? And what does he do with the clues when he finally

figures them out? No court is going to accept the “testimony” of an ape

who constantly bargains to trade questionable descriptions like “skin

bracelet” for yogurt and lollipops (aka “tree candy” in Neema-speak).

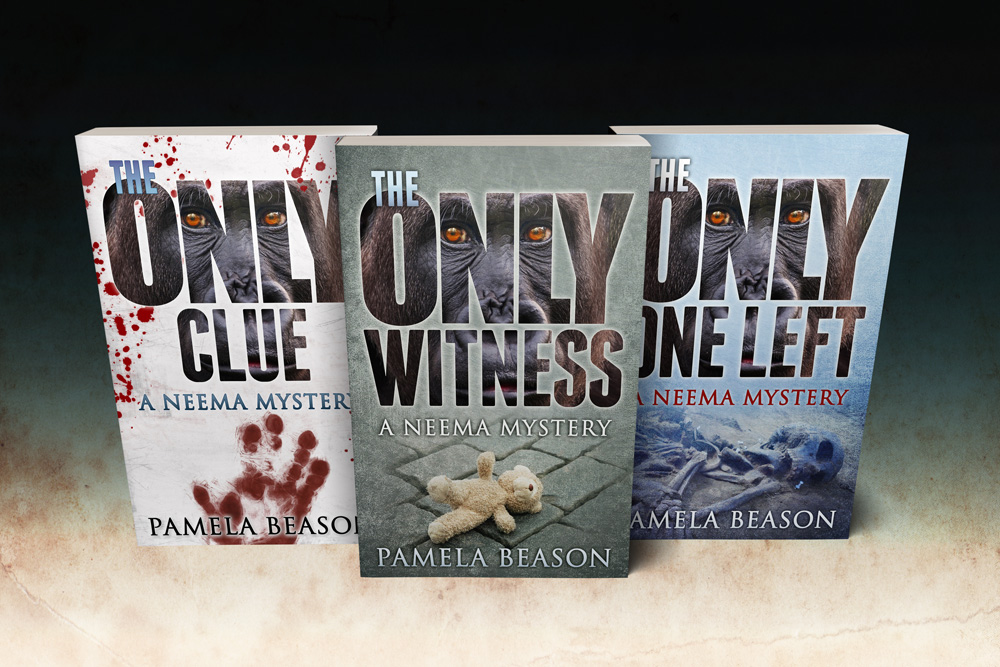

Readers

fell in love with Neema the gorilla and wanted more of her. I’m not

sure anyone even remembered my poor detective’s name, nor that of the

scientist (Grace McKenna) who teaches Neema, or even of the teen mom

(Brittany Morgan) whose infant was kidnapped. So then pressure from

readers forced me to write a sequel with gorillas—The Only Clue, in

which Neema, her mate Gumu, and her baby Kanoni all disappear after a

public event. And then, because any author knows that two books do not a

“series” make, I had to rack my brains to come up with a third. But

just how long can an author invent realistic mysteries involving signing

apes? It’s a challenge, let me tell you.

The Only One Left has sort of a

nebulous connection to a crime, because the gorillas discover evidence

in their barn that Detective Finn eventually deduces may have something

to do with a current case he’s assigned to. But readers don’t seem to

care too much about the premise. The gorillas are back! I like to think

that Koko, the real signing gorilla who passed away not so long ago,

lives on through my books.

Gorilla mysteries are also a marketing

challenge. When asked for other mysteries that are similar to my Neema

series, my response is generally, “Uh…” Likewise, when asked what the

next Neema mystery will be about, I’m clueless as to whether there could

even be another.

So, if anyone has any ideas on either of those

subjects, please send them to me right away. In the meantime, I’ll be

working on the next novel in my Sam Westin wilderness series. It’s so

much easier to solve crimes on public lands than to determine what the

heck three gorillas might be up to these days.

Showing posts with label Pamela Beason. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Pamela Beason. Show all posts

28 June 2019

When the Gorilla Takes Over

14 April 2019

How My Experience as a Private Investigator Affects My Writing

I had to go to Left Coast Crime in Vancouver to run into Pamela Beason, who lives in my town. We hadn't chatted in at least a decade. Go figure.

I asked her to write us a guest piece and she provided this gem. - Robert Lopresti

How My Experience as a Private Investigator Affects My Writing

by Pamela Beason

Although I am now retired from the job, I worked as a private investigator for more than ten years, and that experience definitely impacts how I write my mysteries. Here are a few of the most important points I’ve learned from being a PI and a bit about how they affect my writing:

There’s More Than One Side to Any Story. As a matter of fact, there are as many “sides” as there are people involved. Take a bar brawl, for example. Each combatant will have his or her own story, but everyone in the bar will have one, too. And the cops arriving on the scene might have a completely different idea about what

is going on, because they’ve been told by the dispatcher, who was told

by whomever called 911, what to expect when they arrive. Each person’s

life experiences color his or her opinion of who might be at fault; none

of us is completely objective. It’s fascinating to interview all the

different parties and try to separate perception from reality. This

really helps me concentrate on characterization and point of view in my

novels. If you are a writer, you can do this, too–just pretend you’re

interviewing each character in a scene, and you may be amazed at what

you discover.

have a completely different idea about what

is going on, because they’ve been told by the dispatcher, who was told

by whomever called 911, what to expect when they arrive. Each person’s

life experiences color his or her opinion of who might be at fault; none

of us is completely objective. It’s fascinating to interview all the

different parties and try to separate perception from reality. This

really helps me concentrate on characterization and point of view in my

novels. If you are a writer, you can do this, too–just pretend you’re

interviewing each character in a scene, and you may be amazed at what

you discover.

Criminals Are People, Too. Like most upstanding citizens, I’d love to be able to identify a criminal on sight. In a few cases, we can, but that’s often because those individuals are severely mentally ill as well as being criminals. The scary fact is that many criminals are charming individuals whose company we would enjoy until they do something unethical. I’ve interviewed their victims, whose stories inevitably start out like this: “I liked WhatsHisFace right off the bat, and I liked him right up until he robbed me/stole my car/stabbed me with a kitchen knife.” And when I talk to these criminals (usually in jail, thank goodness), I find them charming, too, although they have really screwy logic. One such fellow told me he shouldn’t be charged with illegal possession of a weapon (he was already a felon) because he really, really, really needed all his guns to protect himself from the bad guys who wanted to steal the drugs he was selling. And, he added, he’d turned his life over to Jesus (again), so everyone really could trust him now. Really.

Sometimes

it’s hard to keep a straight face when talking to these folks. But my

point is that criminals can be loyal to their families and friends, love

their dogs, be fine musicians or artists or accountants, whatever–they

are people. So whenever I create a villain for my book, I try to make

him or her as “human” as possible, too, because this is actually much

more frightening than making them seem evil at first glance.

Sometimes

it’s hard to keep a straight face when talking to these folks. But my

point is that criminals can be loyal to their families and friends, love

their dogs, be fine musicians or artists or accountants, whatever–they

are people. So whenever I create a villain for my book, I try to make

him or her as “human” as possible, too, because this is actually much

more frightening than making them seem evil at first glance.

I have sympathy for former criminals who have just gotten out of prison. Most of us don’t want them living next to us or working for us, but how are they supposed to become responsible, productive citizens if nobody will give them a chance? So, in my stories, I have sometimes made parolees the victims of as-yet-unidentified criminals, because who is likely to believe that a parolee is being framed for a crime he or she did not commit?

Law Enforcement Officers Are People, Too. Police/FBI/Border Patrol, etc–all LE personnel are just as individual as you and I. They can be good or bad at their jobs, well educated or not educated at all (that varies tremendously across the country), prejudiced against groups of people or political or religious affiliations. So I always try to make my law enforcement characters real, too, by giving them flaws and families and individual belief systems.

The U.S. Legal System Is Unequal. As a

matter of fact, it’s so unfair that it was shocking to me when I first

became an investigator. Why is it so hard to be a defendant in our

system? First of all, if you are ever accused of a crime, no matter how

frivolous the accusation, most people will automatically believe you are

guilty. Then, the prosecution has a legal team that generally has

adequate funding, established offices, modern equipment, and so forth,

while the defense team, depending on the situation and locale, could be

anyone. I’ve worked with dedicated but exhausted public defenders and

investigators who received virtually no pay, had no offices, and had to

bring their own pens and paper to the job. How could that possibly be a

fair fight?

The U.S. Legal System Is Unequal. As a

matter of fact, it’s so unfair that it was shocking to me when I first

became an investigator. Why is it so hard to be a defendant in our

system? First of all, if you are ever accused of a crime, no matter how

frivolous the accusation, most people will automatically believe you are

guilty. Then, the prosecution has a legal team that generally has

adequate funding, established offices, modern equipment, and so forth,

while the defense team, depending on the situation and locale, could be

anyone. I’ve worked with dedicated but exhausted public defenders and

investigators who received virtually no pay, had no offices, and had to

bring their own pens and paper to the job. How could that possibly be a

fair fight?

I’ve heard many average citizens say that they’d never need a public defender. Have you looked at the average hourly rate of attorneys recently? It’s $150-$300/hour, and they charge for every minute. Believe me, if we were charged with a felony, most of us would need a public defender. These people and their investigators are saints. Exhausted, often poverty-stricken saints.

So, in summary, when I write a mystery novel, all these elements come into play in developing my characters and building my plots. These bullet points are branded into my brain. And now I hope they’re romping around your brain, too.

Pam was born in Kansas but, like any sensible person, headed to the Pacific Northwest at the first opportunity. She is an outdoors enthusiast - as her list of novels will make clear - and her list of jobs is amazing, ranging from work in a geological research lab,

to managing a multimedia group at Microsoft, to the work described below. You can read more about her writing at http://pamelabeason.com.

How My Experience as a Private Investigator Affects My Writing

by Pamela Beason

Although I am now retired from the job, I worked as a private investigator for more than ten years, and that experience definitely impacts how I write my mysteries. Here are a few of the most important points I’ve learned from being a PI and a bit about how they affect my writing:

There’s More Than One Side to Any Story. As a matter of fact, there are as many “sides” as there are people involved. Take a bar brawl, for example. Each combatant will have his or her own story, but everyone in the bar will have one, too. And the cops arriving on the scene might

Criminals Are People, Too. Like most upstanding citizens, I’d love to be able to identify a criminal on sight. In a few cases, we can, but that’s often because those individuals are severely mentally ill as well as being criminals. The scary fact is that many criminals are charming individuals whose company we would enjoy until they do something unethical. I’ve interviewed their victims, whose stories inevitably start out like this: “I liked WhatsHisFace right off the bat, and I liked him right up until he robbed me/stole my car/stabbed me with a kitchen knife.” And when I talk to these criminals (usually in jail, thank goodness), I find them charming, too, although they have really screwy logic. One such fellow told me he shouldn’t be charged with illegal possession of a weapon (he was already a felon) because he really, really, really needed all his guns to protect himself from the bad guys who wanted to steal the drugs he was selling. And, he added, he’d turned his life over to Jesus (again), so everyone really could trust him now. Really.

I have sympathy for former criminals who have just gotten out of prison. Most of us don’t want them living next to us or working for us, but how are they supposed to become responsible, productive citizens if nobody will give them a chance? So, in my stories, I have sometimes made parolees the victims of as-yet-unidentified criminals, because who is likely to believe that a parolee is being framed for a crime he or she did not commit?

Law Enforcement Officers Are People, Too. Police/FBI/Border Patrol, etc–all LE personnel are just as individual as you and I. They can be good or bad at their jobs, well educated or not educated at all (that varies tremendously across the country), prejudiced against groups of people or political or religious affiliations. So I always try to make my law enforcement characters real, too, by giving them flaws and families and individual belief systems.

I’ve heard many average citizens say that they’d never need a public defender. Have you looked at the average hourly rate of attorneys recently? It’s $150-$300/hour, and they charge for every minute. Believe me, if we were charged with a felony, most of us would need a public defender. These people and their investigators are saints. Exhausted, often poverty-stricken saints.

So, in summary, when I write a mystery novel, all these elements come into play in developing my characters and building my plots. These bullet points are branded into my brain. And now I hope they’re romping around your brain, too.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)