Another thing is economics. Everyone complains about taxes, prices, and how expensive it is to live any more. I'm not going to go into taxes - that way lies madness. But I can tell you that living has never been cheaper. We live in a country awash in stuff - food, clothing, appliances, machines, cheap crap from China - but it's never enough. $4 t-shirts? Please. We want five for $10, and even then, can we get them on sale? And yet, compared to a world where everything is made by hand - we're talking barely 200 years ago - everything is cheap and plentiful, and we are appallingly ungrateful.

Let's talk clothing. When the Industrial Revolution began, it started with factories making cloth. Why? Because clothing used to be frighteningly expensive. Back in my teaching days I gave a standard lecture, which is about to follow, on the $3,500 shirt, or why peasants owned so little clothing. Here's the way it worked:

NOTE: As of 4/6/16 I have updated the mathematics of this here at this blog post. It's still astounding.

See this guy below, lying asleep under the tree? And the guys still working in the field? They're all wearing a standard medieval shirt. It has a yoke, a bit of smocking and gathering around the neck, armholes, and the wrists would be banded, so they could tie or button them close.

Oh, and in the middle ages, it would be expected that all of the inside sleeves would be finished. This was all done by hand. A practiced seamstress could probably sew it in 7 hours. But that's not all that would go into the making. There's the cloth. A shirt like this would take about 5 yards of cloth, and it would be a fine weave: the Knoxville Museum of Art estimates two inches an hour. So 4(yards)*36(inches)/2 = 72 hours. (I'm a weaver - or at least I used to be - so this sounds accurate to me.) Okay, so hand weaving and hand sewing would take 79 hours. Now the estimate for spinning has always been complex, so stick with me for a minute: Yardage of thread for 4 yards of cloth, one yard wide (although old looms often only wove about 24" wide cloth), and requires 25 threads per inch, so:

9,000 yards would take a while to spin. At a Dark Ages recreation site, they figured out a good spinner could do 4 yards in an hour, so that would be 2,250 hours to make the thread for the weaving. Now, A lot of modern spinners disagree with this figure, saying they can spin much faster than that. So let's say they're right. And we'll say that the spinner is in a hurry to make this thread because the shirt's for her or someone she knows (all spinners were female in medieval times), so we'll say she worked her tail off and did it in 500 hours.

So, 7 hours for sewing, 72 for weaving, 500 for spinning, or 579 hours total to make one shirt. At minimum wage - $7.25 an hour - that shirt would cost $4,197.25.

And that's just a standard shirt.

And that's not counting the work that goes into raising sheep or growing cotton and then making the fiber fit for weaving. Or making the thread for the sewing.

And you'd still need pants (tights or breeches) or a skirt, a bodice or vest, a jacket or cloak, stockings, and, if at all possible, but a rare luxury, shoes.

NOTE (1/30/15) - Please see a further commentary on this piece at: Is Time Money or is Money Time?

NOTE: Back in the pre-industrial days, the making of thread, cloth, and clothing ate up all the time that a woman wasn't spending cooking and cleaning and raising the children. That's why single women were called "spinsters" - spinning thread was their primary job. "I somehow or somewhere got the idea," wrote Lucy Larcom in the 18th century, "when I was a small child, that the chief end of woman was to make clothing for mankind." Ellen Rollins: "The moaning of the big [spinning] wheel was the saddest sound of my childhood. It was like a low wail from out of the lengthened monotony of the spinner's life." (Jack Larkin, The Reshaping of Everyday Life, p. 26)

Anyway, with clothing that expensive and hard to make, every item was something you wore until it literally disintegrated. Even in 1800, a farm woman would be lucky to own three dresses - one for best and the other two for daily living. Heck, my mother, in 1930, went to college with that exact number of dresses to her name... This is why old clothing is rare: even the wealthy passed their old clothes on to the next generation or the poorer classes. The poor wore theirs until it could be worn no more, and then it was cut down for their children, and then used for rags of all kinds, and then, finally, sold to the rag and bone man who would transport it off to be made into (among other things) paper.

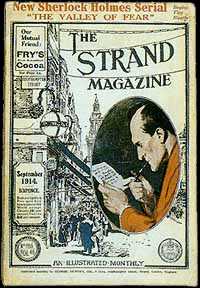

And speaking of paper, that was another thing that had to be invented for our society to exist: cheap paper. Good rag paper (made literally with expensive cloth rag) was always pricey, just not as pricey as parchment which was goat, sheep, or calf skin. (This is why medieval manuscripts were so few and why they were often kept chained up for fear of theft. It took at least a whole herd of animals to make the Book of Kells, for example. On the other hand, well-kept parchment can last thousands of years.) In fact, paper remained expensive long after clothing got cheaper, because it took a long time to figure out how to make paper out of nothing but wood pulp, without all that expensive rag content. It wasn't until the production of wood pulp paper was perfected in the mid-1800's that books (schoolbooks, fiction, non-fiction), magazines, and newspapers became available to the general public. Including pulp fiction - the first was Argosy Magazine in 1896 - a genre that was named for the cheapest of cheap fiber paper that it was published on. And without that pulp paper, where would our entire genre be?