I read a book this past week that my sister gave me, A Killer in King’s Cove, the first of a mystery series by Iona Whishaw, a Canadian writer new to me but maybe not to the rest of you – the first book came out in 2015, her most recent in 2024, eleven of them so far. King’s Cove is set in 1946. The heroine, Lane Winslow, an SOE courier and clandestine op in Occupied France during the war, and troubled with PTSD, has exfiltrated herself to the woods of British Columbia, wanting to leave her past behind. Not, of course, to be. Lane, much like her cousin in spirit Maisie Dobbs, is fated by temperament, a sense of duty, and her fatal curiosity, to be drawn toward the flame.

I’m making it sound more melodramatic than it is. The story-telling is relaxed and even a little shaggy-dog, not my usual preference for hard-boiled blunt force trauma. It leans on charm - by which I don’t mean fey, or whimsical, or labored hillbilly slapstick. Characters who present as genuine, not tics or tropes. Round, in other words, in the use of the word E.M. Forster gives us, not flat. There’s something, I may say, Canadian about this, as distinct from British, a very different kettle of fish.

This is actually where I’m going, here. Another book I read, recently – again, a gift, so not something I might necessarily have stumbled on, all by my lonesome – is The Lost Man, by the Aussie writer Jane Harper, known on these shores for The Dry. And then there’s the thoroughly subversive In the Woods, an Irish procedural, Tana French’s debut novel, which I also picked up this year.

The mystery story is essentially conservative. This isn’t an original observation, on my part. It’s generally agreed to. The social compact is broken, murder being the most grievous breach of the common good, and the cop, or the private dick, or the avenging angel, knits up the raveled sleeve, and repairs the damage. This is the classic set-up of an Agatha Christie, or S.S. Van Dine; not that it isn’t corny, and readily parodied, but Christie, for all that she may be dated, still puts the bar pretty high. And moving forward, to somebody like Ross Macdonald, even at his most anarchic, in The Chill, say, the larger purpose of a social good is served.

Having

said that, I’ve noticed some things mysteries and police procedurals don’t have in common, when set in exotic

locales: not Christie, in Death on the

Nile, or Martin Cruz Smith’s Arkady Renko books, the visiting fireman, but

homegrown. We’re used to the attitudes

and accents of an Inspector Morse, or an Inspector Lewis, because we’ve seen a

lot of PBS Mystery, and we’ve accustomed

ourselves to how the Brits present these kinds of stories. Cable broadens the overview. I’ve mentioned Dr. Blake (Australian), Brokenwood

or My Life Is Murder (

Here’s

my point. Watching this stuff, which can

come from very different cultural biases, you can be thrown off. The case of Tatort, for example. The

series will do half a dozen episodes per season in a particular German city, so

each season you get a few in

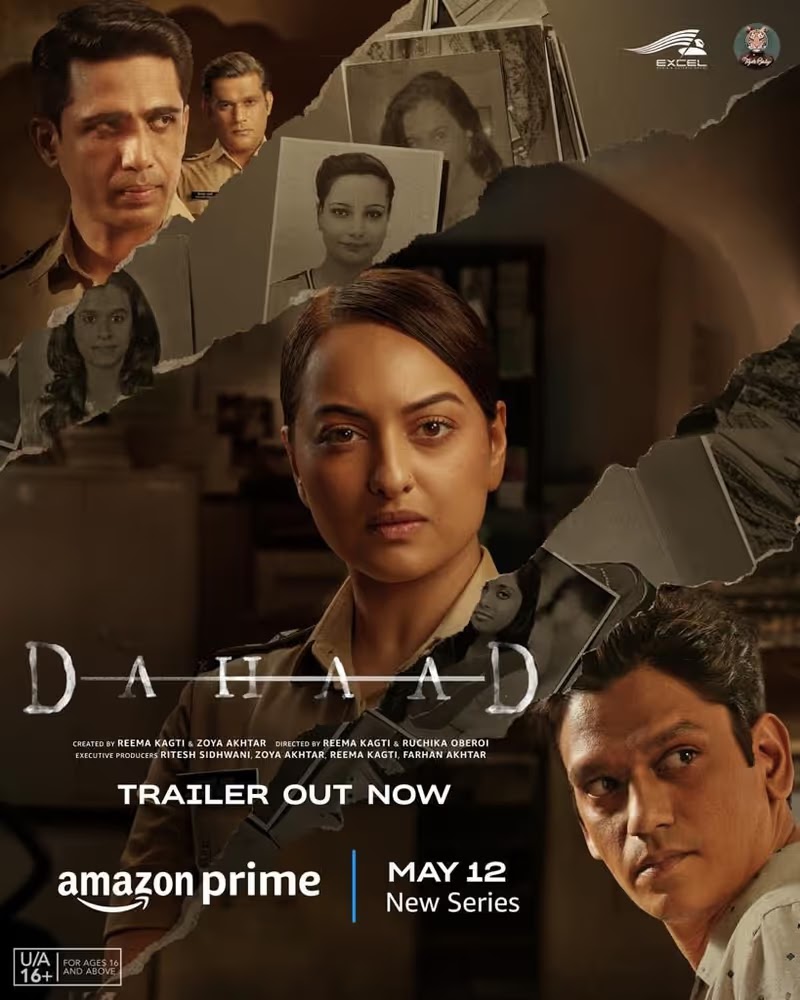

Same thing with Dahaad, this dissimilarity, or cognitive dissonance. If you’re used to the rhythms of Bosch, or The Wire, or Barney Miller, for that matter, watching the beleaguered but furiously obstinate Bhaati and Singh fight their corner against religious politics, misogyny, caste prejudice, and plain willful ignorance is really something to behold. Any lesser person would cave. And although you might harbor the suspicion that Bollywood is going to simply paper over these intransigent differences in favor of a happy ending, by the actual end, you’re pleased not to be drowned in cynicism, although the happy is ambiguous.

We find, maybe, that something’s gained in translation, rather than lost. I know there are other examples of this phenomenon that don’t in fact work, because I’ve tried to watch them and given up, but that doesn’t signify. What’s fascinating to me is how these shows manage as best as they do, to tell stories that only work in their own context. It seems obvious, but it’s not, that the conventions of a narrative depend on the inner tension between discipline and chaos, and arbitrary social structures aren’t just good manners, but a survival mechanism. In this particular narrative construct, the Western hero is often an avatar of indiscipline; that’s not the only model for a story.